Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

We have a look at some of the things we did, as a two-person indie team, to make Dialogue more accessible.

Tea-Powered Games is a small company, we’re just two co-directors (writer and designer) who hired freelancers to finish our first game, Dialogue: A Writer’s Story. One of the things we’ve focused on from the start has been to make our games accessible to as many people as possible. Just because we’re a small team doesn’t mean we couldn’t look for ways to help as many people play our game as we could. Now that we’ve finished work on Dialogue, we want to share some of the decisions we made and why.

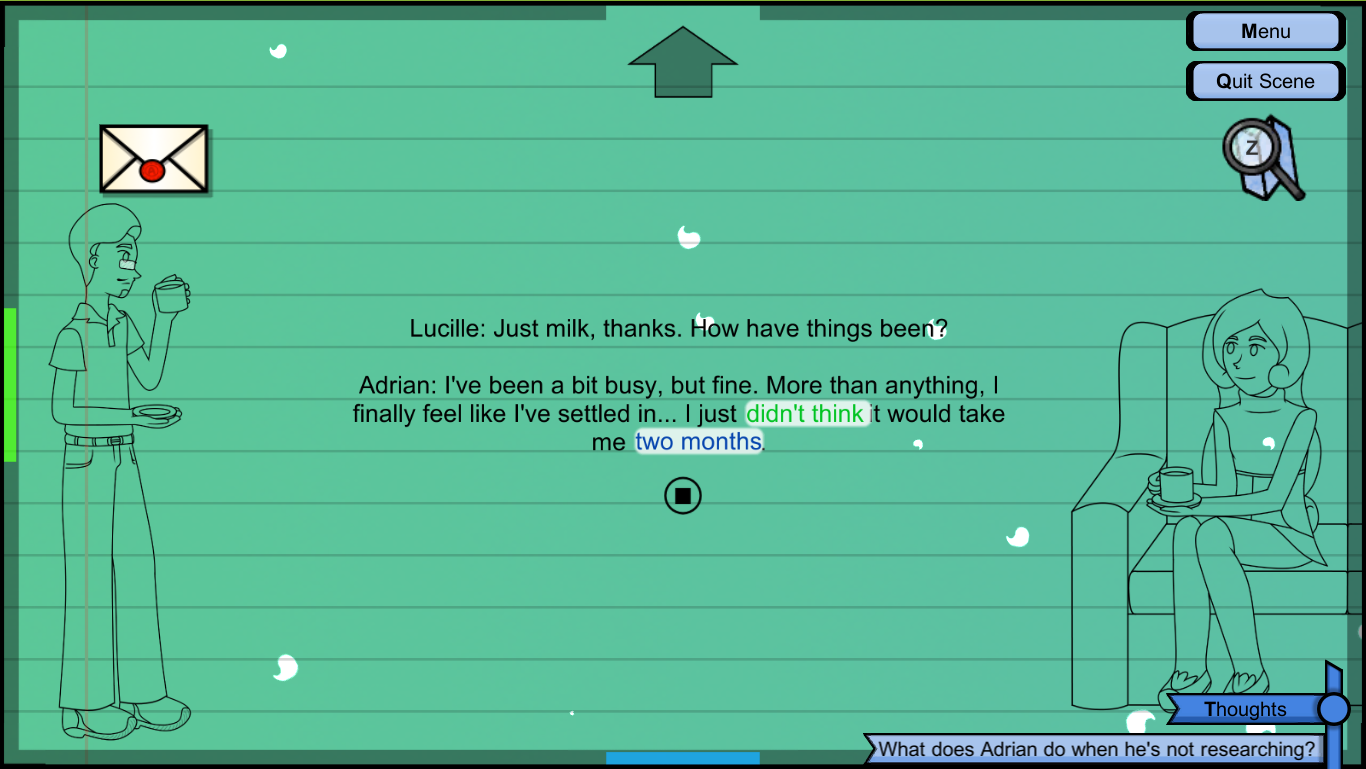

First, here are some of the key features of Dialogue, which will be useful to understand our decisions. Dialogue is somewhere between an RPG, visual novel and various other types of interactive fiction. It follows the story of Lucille as she writes her second novel, a science fantasy volume inspired in part by her biochemist neighbour, Adrian. It consists of two major types of conversations.

Active conversations occur in real-time, moving at the speed of the voice actor’s lines. Player options appear and disappear in limited time frames, and players can equip Focuses to change how the conversations play out. These Focuses give extra information, or give players more strategic options, among other things.

Exploratory conversations map different subjects spatially, allowing for backtracking and finding new paths. The player can use Thoughts, questions to be answered in the text itself, to open up new branches of conversation.

Game literacy/comfort

We wanted to make sure anyone could pick up the game and play, even if they didn’t have much, or any, experience with game terms or skills (game events open to a broader public were a good place to test this!). While most games want to have good tutorials, or not overload the player with information, we wanted to go a bit further than that.

There are no fail states in Dialogue. No one can ‘fail’ at going through the main story, just as no one can ‘fail’ at going through their life (or so we like to believe).

The game doesn’t require dexterity or puzzle-solving skills to progress. There are certain rewards unlocked by answering questions correctly or speaking to a character a certain way, but that never blocks progression.

We wanted players to learn more about characters and their preferences, since it’s a game about conversations, but we didn’t assume all players would do so equally. We gave players Focuses so they could opt into receiving more information, if they wanted to.

Players can replay scenes as many times as they want, meaning they can spend more time learning what works and what doesn’t with different characters. We don’t want them to feel like they missed a chance to get to know a character – they can just chat with them again.

Scenes are kept relatively short, so the player has a broad choice of exit points. We didn’t want to assume players would always have time for more than a 10-15 minute session.

There are as many tutorial messages as we found were helpful for players. These are also stored in the Help menu, in case the player wants to check them again.

The Main menu has a short description of the last scene that was played, and some information on the upcoming scene, so players can jump back in no matter how long it’s been or how much they remember.

Subtitles and Voice acting

We always wanted voice acting for Dialogue – it’s what allowed us to do Active conversations in the first place. It made for a tough start to Dialogue, and we had to make certain sacrifices for it. The script had to be finalised early for voice recording, and with our budget, there wasn’t time for a lot of retakes, or re-recording of lines after the initial voice acting. However, we think it was a very important part of Dialogue.

Voice acting means we don’t make assumptions about player reading speeds. Our early prototypes without voices, using timed text in twine, showed us just how much of a difference reading speed made to people’s enjoyment of the game.

All conversations have subtitles, which we tried to make as legible and colour-contrasted as possible. It was important to us to have both voice and text whenever possible. The volume levels for the voices, music and sound effects all have separate sliders as well, so players can ensure they’re hearing what they need.

Players can affect the pace of conversations to better suit their preferences. Using a Focus from early in the game, Consider, gives the player more time to read, think and make decisions. Another early Focus called Know-it-all lets them skip through text faster.

Colour-blind mode

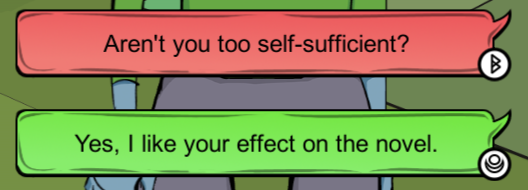

In Active conversations, we wanted to get across Lucille’s tone for each statement without unintended connotations. If we used words to label a statement as ‘aggressive’ or ‘direct’, for example, players might read too much into that word, or we would need too many words as descriptors. We use colours to label these options instead. This lets players make their own assumptions about what each colour means.

In order to let all players use the same tools, we added a colourblind mode that can be toggled on or off. When it’s turned on, options have distinct symbols that are abstract, but the player can attach meaning to, as with the colours.

While we used different colours for the subtitles of different characters, the speaker is always under a spotlight, to make it easy to tell who is speaking even without the colour information.

Input methods

The more input methods a game has, the more people can play it, or feel comfortable with it. While Dialogue started as a mouse-controlled game, we spent some time adding keyboard and gamepad controls. This means that the game plays best on a mouse, but we spent enough time on other controls that it works relatively smoothly. Dialogue can be played fully with either the mouse, a keyboard or controller, or a combination of the above (I have definitely taken advantage of the combinations of controls to speed through conversations).

Unfortunately, there are things we struggled to do, because we didn’t have the time, resources or expertise. These are some things we’re trying to do better in our future games, or would change in Dialogue if we had the opportunity.

Translating the game

We would have loved to bring Dialogue to multiple languages, but it’s not an easy game to localise. The script is long and the game is fully voice-acted, so as our first game, it would have been a challenge, even if we only translated the subtitles. For any future word-heavy games, we’ll be looking for ways to make it easier to localise our game from the get-go, such as making sure our script has space for lines in different languages and links to the voice files, or that our buttons containing text aren’t so small that translations need to be highly constricted.

Button reassigning and Controls

While Dialogue can be played on keyboard, controller or mouse, we would have wanted to let players reassign their keyboard or controller buttons, to make it accessible to even more people. We assigned buttons based on what made the most sense to us (arrow keys to move between options, Enter to select things) but we know that is still a compromise.

There were a few other things in this vein that didn’t make it into Dialogue, such as letting players rearrange the User Interface elements, or changing the color/size of text.

Better representation within our characters

Dialogue has a relatively small cast, and a large portion of the characters are either Lucille’s family or (somewhat fantastical) characters from her novel. In future games, we want to make sure to have characters representing a broader range of people, both to make it more accessible to the people we’re representing, and to make more interesting games.

Platform

Dialogue was mouse-controlled from the beginning to ensure we could use touch controls as well. Especially in its early forms, Dialogue would have been at home on tablets, and that would have reached a wider audience than PC/Mac alone. However, by the time we started looking into what that would entail, many assets were finished and it would have meant a large amount of extra work, so that idea is left for our future games.

We are also testing a Linux version of Dialogue, which we hope to complete soon.

As a small studio, there were limitations on what we could do, but we wanted to explain some decisions which we think help bring Dialogue to a larger audience. Some of them are quite common (such as legible subtitles), while others (like not having a fail state) only work for certain kinds of games. We also know that there’s always room for improvement. If you get the chance to play Dialogue, or can think of more things a game like ours could use, let us know!

-Florencia

Dialogue is out on November 8th for PC/Mac on itch.io, and is currently on Steam Greenlight.

Website: www.teapoweredgames.co.uk

Contact us at: [email protected]

Dialogue on Greenlight: http://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=783074552

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TeaPoweredGames/

Twitter: @teapoweredteam

Game Accessibility Guidelines: http://gameaccessibilityguidelines.com/

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like