Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Excerpting from his 'Dungeons & Desktops' book on the history of CRPGs, Barton looks at 'The Silver Age' of role-playing games, from Richard Garriott's Ultima I through Sir-Tech's Wizardry and beyond.

[In this excerpt from his newly published book Dungeons & Desktops, Matt Barton explores the "silver age" of RPGs on computers. This article covers the emergence of the Ultima series and a host of other exciting, innovative titles that blew up in the 1980s. Dungeons & Desktops has its genesis in a series of pieces Barton wrote for Gamasutra in 2007, which can be found here: The Early Years, The Golden Age, and The Platinum and Modern Ages.]

In 1981, the CRPG was still in its infancy. Programmers were refining their techniques and discovering the true capabilities of personal computers. More importantly, standards were emerging that would greatly improve interfaces, making CRPGs much more intuitive and far less cumbersome. So far, most CRPGs had been of interest only to hardcore role-playing fans already intimately familiar with D&D conventions.

These games lacked the sort of user friendliness that would have made them accessible to a larger audience. In any case, many gamers didn't relish the idea of learning one role-playing system just to abandon it when the next game came out.

The solution came in the form of long-running series, such as Ultima, Apshai, and Wizardry. Once gamers had mastered the interface, they could move on to the next game in the series with relative ease. As we'll see, these series had benefits for both developers and gamers, and they mark an important turning point in the history of the CRPG.

The most important games of the Silver Age are Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness and Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord (both 1981). Both games launched successful and influential series that lasted into the 2000s, but it was Ultima that catapulted the genre into the mainstream -- indeed, its influence even extended overseas and inspired the Japanese console RPGs that so many of us are familiar with today. We'll talk about the first three Ultima games in this chapter.

Garriott had justifiably high expectations for his new Ultima series, which soon became the standard by which all other CRPGs were judged.

Wizardry, meanwhile, earned a reputation for challenging, hardcore gameplay. It also demonstrates what would become a long and established practice of "engine recycling," or reusing the bulk of a game's code in subsequent games. This technique allowed developers not only to create games faster and for less cost, but also to focus more on developing content, such as graphics and stories.

Tension began to build between gamers who expect sequels to be quite radical revisions and those who resent such changes and demand consistency -- a tension brought out nicely by comparing the Ultima and Wizardry series.

The Silver Age also saw several other important and influential games, such as Telengard, Sword of Fargoal, Dungeons of Daggorath, Tunnels of Doom, and Universe. Each of these games introduced or affirmed gameplay concepts that would show up in countless later games, and each vividly demonstrates the diversity of the genre in the early 1980s. They're also some of the more beloved of the early CRPGs and are still regularly played today by hundreds if not thousands of nostalgic gamers around the world.

After his success with Akalabeth, Garriott was infused with ambition and determined to make a new game that would make the other seem primitive by comparison. Garriott considered his earlier game a hobby project that had stumbled into the commercial sector by accident: "I had been working for my own enjoyment and edification, not my dinner."

The new game would be a commercial endeavor from the start, targeted at a larger audience. Garriott teamed up his friend and coworker Ken Arnold (nicknamed "Sir Kenneth") to create a tile-based graphics system reminiscent of a miniatures tabletop, which requires much less storage space and allows for large, colorful environments.

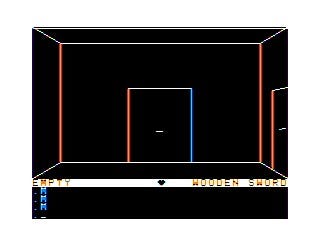

Garriott used this system to depict the vast countryside but incorporated the wireframe, first-person perspective of Akalabeth for the dungeons. Switching between these perspectives gave players of the game an impression of vastness; the game felt more like a world than a dungeon. The product was finished in 1981, and Ultima was published by California Pacific, the same company Garriott had relied on for Akalabeth.

Perhaps what impressed gamers and critics more than the graphics was the truly epic size of the game. Indeed, rather than limit itself to one time period, the setting moves from the Middle Ages to the Space Age. There's even a sequence featuring first-person perspective space flight and combat! Critics marveled at how characters starting off with maces and other crude weapons ended the game with phazors and blasters.

There are also several nice twists, such as monsters (gelatinous cubes) that destroy armor and others that take the character's food. As with the previous game, food is a serious and constant concern. However, if the character dies, the player can try to resurrect him. The only problem here is that the character might materialize on a water tile and be unable to move away -- an infuriating bug.

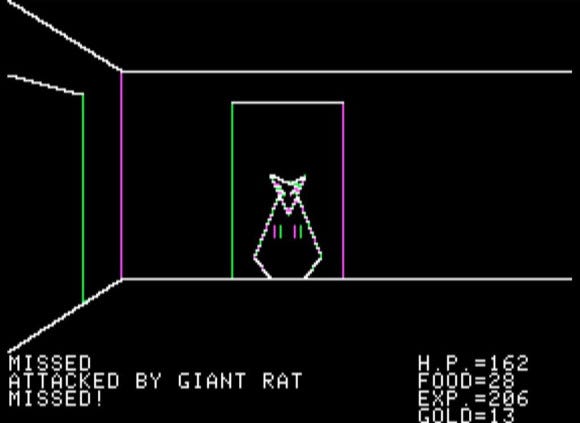

The early Ultima games offered monochromatic wireframe perspective in dungeons. Garriott had developed these techniques in the earlier Akalabeth.

The game also handles hit points in an unusual way. Instead of regenerating by resting or healing, the character must either buy hit points from the king or receive them as he leaves dungeons. Of course, if the player runs out of hit points, the character dies and must be resurrected. I'm not sure the system makes much logical sense, but it didn't seem to arouse much disdain from critics.

The system also differs somewhat from D&D rules for character creation -- instead of rolling randomly for stats, the player is given 90 points to distribute across six categories: strength, agility, stamina, charisma, wisdom, and intelligence.

Of course, a sensible distribution depends on the choice of type, or class: fighter, cleric, wizard, or thief. There are four races to choose from, one being hobbits -- perhaps a nod to Tolkien. We'll see this point distribution system show up in many later games, though it's unclear if it's really an improvement over the more traditional model based on rolling three six-sided dice.

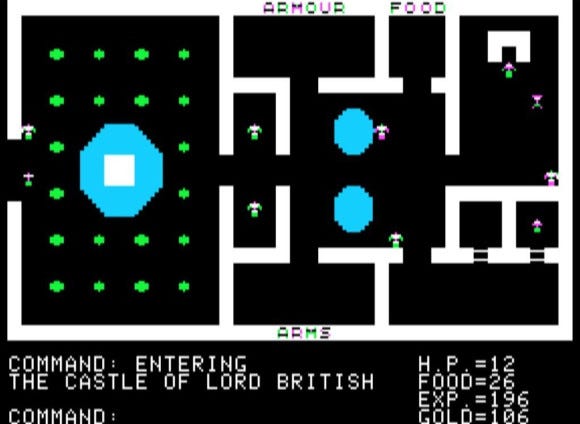

In addition to the 3D dungeons, Ultima featured colorful top- down modes. Here's the famous Castle of Lord British, who is seen here in the throne room on the upper right.

The storyline builds on Akalabeth's. The evil wizard Mondain has enslaved the lands of Sosaria using a gem of power that makes him completely unstoppable. It's the player's mission to travel back in time and kill him before he can make the gem and take over the world. Solving the game means traveling across vast distances, fighting random encounters along the way.

The game was originally available only for the Apple II+, though ports followed for the Atari 8-bit computers in 1983. In 1986, the game was rewritten in assembly language and updated with better graphics and a few other small changes. This version was ported to the Commodore 64, MS-DOS, and MSX platforms and is more familiar to most gamers than the original.

Ultima was an unqualified success, and Garriott wasted little time producing the sequel. However, Ultima II: The Revenge of the Enchantress (Aug. 1982), was published by Sierra On-Line rather than California Pacific, which had somehow managed to bankrupt in the interval.

Garriott, always a stickler for how his games were packaged, chose Sierra because the company was more responsive to his idea to include a cloth map with the game (apparently, this decision was influenced by Garriott's obsession with Terry Gilliam's 1981 film Time Bandits, which features a similar contrivance). The second game offers several improvements, such as the ability to talk to nonplayer characters and some routines written in assembly language that increased the game's speed. It also doubled the number of tiles used for the graphics, a noticeable and desirable improvement.

Like the first Ultima, The Revenge of the Enchantress is another mix of fantasy and sci-fi elements. This time, it's not Mondain but rather his apprentice and lover, Minax, who aims to eradicate the human race by instigating a nuclear war. Again the player has to track down a magical item needed to destroy her, a quest that involves traveling to several villages, time periods, and even planets.

It's an enormous game whose impressive scope is comparable only to Sierra's other big game of 1982, Time Zone, a sprawling $100 graphical adventure game by Roberta Williams. However, Ultima II contained several bugs, and some critics complained that the game had a rushed, unpolished feel. Nevertheless, the game sold even better than the previous one.

The second Ultima game was as ambitious as the first, though Garriott's relationship with Sierra eroded quickly.

When it was time for Ultima III, Garriott decided to break from Sierra and publish the game under his own new company, Origin -- primarily a family company consisting of his brother and their two parents. Garriott did not leave Sierra on good terms, however. According to a 1986 interview published in Computer Gaming World, he felt that Sierra "did not seem very author friendly," and that "I never really knew if I was getting a fair shake."

What exactly did Garriott have in mind when he made these comments? Some sources claim that the comments refer to an argument about the royalties for the IBM PC port of Ultima II. When Garriott had signed his contract with Sierra, the IBM PC didn't exist, and was not factored into the royalty agreement.

According to Garriott, Sierra offered him a "take it or leave it" arrangement with lower royalties than he felt he deserved. This is the explanation offered by Shay Addams in his The Official Book of Ultima and suggested by Wikipedia.

However, the problem may have something to do with an exceptionally rare game called Ultima: Escape from Mt. Drash, published in 1983 exclusively for the Commodore VIC-20. The game was programmed by Keith Zabalaoui and released without Garriott's knowledge or permission (and most likely against his wishes). Ever the perfectionist, Garriott was likely upset with the Mt. Drash fiasco, seeing it as the worst sort of exploitation.

In any case, Escape from Mt. Drash was a poor seller and is so ultra rare today that it has become a Holy Grail for many collectors of vintage software. In 2003, the loose data cassette alone fetched $865 in an online auction.

The game itself is a rather simplistic dungeon crawl, though one featuring a three-sectioned interface and 3D dungeons. A review in the July/August of Computer Gaming World praises its "unique graphics and marvelous musical score," but its collectability undoubtedly owes more to controversy than quality. Addams doesn't even mention it in his Official book.

If the first two Ultima games were impressed critics and pleased gamers, Ultima III: Exodus knocked their sabatons off. First published in 1983 by Origin, the third Ultima was an instant success, forever establishing Garriott as a true master of the genre: a "veritable J. R. R. Tolkien of the keyboard," according to one magazine reviewer.

The game would go on to influence not only countless other CRPGs in both the West and the East, where it led to the development of Japan's console RPGs such as Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy. It's certainly no exaggeration to call it one of the most important CRPGs ever made and the pinnacle of the Silver Age.

Several innovations make the game stand out from the earlier games. The most obvious is that the player is asked to control a party of four adventurers rather than a single hero. By this time, another CRPG series called Wizardry (which we'll discuss later in this chapter) was making its presence felt, and Garriott felt that since "Wizardry had multiple characters, I needed them too."

It also features a tactical, turn-based combat system with strict time limits (if a player takes too long to move a character, the game automatically skips to the next character or monster's turn). There are 16 hand-to-hand and ranged weapons, eight armor types, and 32 magic spells with names inspired by Latin.

One unusual and somewhat frustrating aspect of the combat system is that only the character striking the deathblow gets any experience points for the battle -- a fact that can quickly lead to a severely unbalanced party. Garriott also reworked the scenes involving sea travel, introducing a ship-to-shore combat system and wind navigation. To top it all off, the Garriott added a dynamic musical score that changes with various settings, though Apple II owners needed the optional Mockingboard expansion card to hear it.

The third Ultima game offers solid-color dungeons and a sharp layout.

Another important innovation is the fixed dungeons. Rather than random and mostly irrelevant dungeons, Ultima III integrates a series of stable dungeons directly into the gameplay, perhaps as a response to the frequent complaint that the dungeons in the previous games were practically superfluous. Furthermore, the dungeons in Ultima III aren't wireframe, but solid color and reminiscent of later CRPGs such as The Bard's Tale (1985), though predated by Texas Instruments' Tunnels of Doom (1982).

The storyline is rather typical and avoids the sci-fi elements that played such an important role in the first two games. Simply put, the player must seek out and kill an evil overlord, this time one named Exodus. Exodus is the offspring of Mondain and Minax and has been terrorizing the land of Sosaria with no regard for diplomacy.

Solving the game requires seeking out the mysterious Time Lord and working out the secrets of the Moon Gates. It isn't enough just to build up a strong party, though -- players must interact with townspeople to gather enough clues to solve a series of puzzles.

Ultima III was a smash hit, selling some 120,000 copies and cementing Lord British as the foremost maker of CRPGs. It was ported to most of the available platforms of the day and later even to the NES.

The Ultima series would dominate the CRPG scene for years, and even after its popularity waned in the face of increasingly fierce competition, plenty of loyal fans hung on. Even today, over 100,000 gamers still subscribe to Ultima Online, an MMORPG based on the franchise. We'll have more to say about the series as we discuss the later ages.

Although Garriott's Ultima series is the best known CRPG of the early 1980s, it was certainly not alone. As early as 1981, a worthy competitor had thrown down the gauntlet: Sir-Tech.

Founded by Robert Woodhead and Norman Sirotek, Sir-Tech would soon earn a reputation for extraordinarily challenging yet well-designed CRPGs. Its Wizardry series did much to standardize the genre, and would remain vital throughout the 1980s and early 1990s (the eighth and final game was published in 2001).

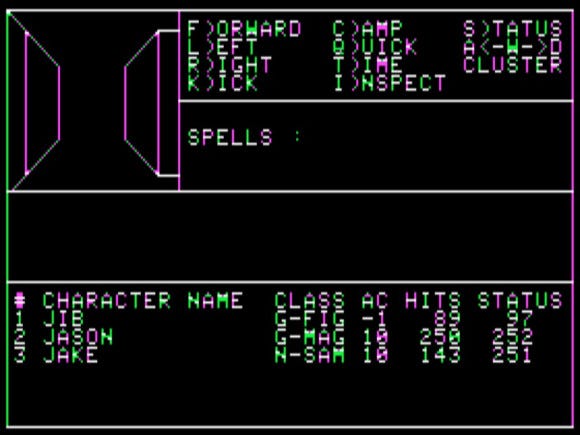

The first of these games is Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord, published in 1981 for the Apple II (and in 1987 for other platforms). Unlike Ultima, Wizardry allowed players to create their own parties of up to six characters, who could be almost any mix of five different races (humans, elves, dwarves, gnomes, hobbits), four starting classes (fighter, mage, priest, thief), and three alignments (good, neutral, evil). (I say almost here because good and evil characters can't join the same party.)

After these selections, the player must distribute a random number of bonus points among six stats (strength, I.Q., piety, vitality, agility, and luck). Needless to say, going through this cycle six times can be quite a bit of work, particularly if the player is determined to create the best possible party. The manual puts it well: "Playing Wizardry for the first time is like kissing for the first time -- you want to do it right, and you're not quite sure exactly what you are supposed to do."

Wizardry offers a smooth first-person interface and puts the player in charge of a whole party of adventurers.

Creating a group rather a single character leads to a much different gameplay dynamic, since players have to carefully balance their parties to ensure that they have the right combination of skills necessary to complete the ten-level dungeon.

In other words, players are required to make many important decisions before gameplay commences; the character creation process is long, involved, and of paramount importance. A few poor selections can easily make the game extremely difficult, if not unwinnable. Many less experienced gamers were no doubt overwhelmed by the whole process. We'll return to the "party versus single hero issue" later.

Further complicating the party issue are four elite classes, which are more or less hybrids of the four basic classes: bishop (priest/mage), samurai (fighter/mage), lord (fighter/priest), and ninja (fighter/thief). The ninja is similar to what many later games would call the monk, a fighter that shuns weapons and armor and excels at critical strikes.

There are some alignment restrictions as well: bishops can't be neutral, samurai can't be evil, lords must be good, and ninjas must be evil. The elite or prestige class is something that will show up again later in The Bard's Tale (1985) and many later CRPGs.

The magic system is also fairly elaborate, with some 50 total spells for priests and mages. Perhaps as a tactic to ensure that players purchased a legal copy of the game, these spells can only be cast by entering their names -- printed in the manual, of course.

Although most of the spells are combat-related, a few are useful in other ways. For example, the mage spell "DUMAPIC" reveals the player's current position in the maze relative to the stairs leading out of the maze, and "MALOR," if cast in camp, will teleport the party to a precise location. The magic system uses a special spell point system involving slots for each level of spell. These points can only be replenished by resting in The Castle.

Like Akalabeth, Wizardry portrays the dungeons (called The Maze) in 3D wireframe graphics and first-person perspective. However, one nice innovation is that when battle is joined, the dungeon graphic is replaced by a color portrait of one of the attacking monsters (up to four groups of them can attack). It's a great opportunity for art, and we'll see it countless later games, such The Bard's Tale and The Pool of Radiance (1988).

The dungeons are arranged on a 20 x 20 grid, which makes them ideal for mapping onto graph paper. Since the dungeons are fixed rather than random, players could really benefit from having a good map laid before them. The map offers detailed instructions on making such a map and lets player know that "mapping is indeed one of the most important skills that successful Wizardry players possess."

Whereas some gamers found the task irksome, others enjoyed it almost as much as playing the game. I find the cartography fascinating, especially when I consider how CRPGs evolved from Colossal Cave and other exploration games. Mapmaking remained a critical skill for many years to come, at least until CRPGs began featuring automapping tools.

The storyline of Wizardry is standard fare. The Evil Wizard Werdna has stolen a magical element from Trebor (Robert spelled backwards), the Mad Overlord. Furthermore, Werdna has used the amulet to create a ten-level fortress maze beneath Trebor's castle. Trebor has declared this maze his bodyguards' proving grounds, and of course it's up to the party to descend into it, battling whatever monsters stand between them and the amulet. It's easy to see the connections to the older mainframe games, many of which offer the same quest for an all-powerful magical amulet.

Wizardry was created by Andrew C. Greenberg and Robert Woodhead, then students at Cornell University, who spent some two and a half years developing it. The reason for the delay was that the game had originally been programmed in BASIC, but that language had proven too inefficient for the game to run smoothly on an Apple II.

They converted the game to PASCAL, a decision that it made it much easier to port the game to other platforms later on. Unfortunately, PASCAL programs required 48 K of RAM to operate, and Apple II needed an optional RAM expansion called a Language Card to run them.

It wasn't until 1979 that Apple introduced the Apple II+, which came preequipped with the required 48 KB of RAM. In short, Greenberg and Woodhead were at least a year ahead of the technology and had to wait for gamers and the computer industry to catch up with them.

Wizardry brings us to an interesting question about CRPGs. Is it better to control a party or a single adventurer? One way to answer this question is by posing another: which is more like tabletop role-playing games?

On the one hand, almost all conventional D&D games involve groups of players and their characters. Usually, Dungeon Masters will encourage the players to select characters who complement one another, the ideal being at least one of each basic type (fighter, thief, cleric, and mage).

This way, the characters can work together to devise strategies and overcome obstacles -- for instance, a sorceress might be extremely vulnerable in hand-to-hand combat, but devastatingly effective at range; it becomes the fighters' job to occupy the monsters so that she can cast her spells. Thus, it would seem that party-based games like Wizardry and Ultima III are closer to the D&D model.

On the other hand, D&D players only control one character at a time and are asked to assume the role of that character during the session. Looked at from this perspective, single-hero games like Ultima and Rogue are closer to the ideal, since it's much easier (theoretically, at least) to identify with a single character than a whole group of them.

Unfortunately, this problem has yet to be solved, and CRPG fans and developers have long been divided on the issue. Currently, the industry seems to have settled on the single-hero model; of the top three CRPGs currently available, none is party-based. We'll return to this critical issue throughout the book.

The next two Wizardry games are The Knight of Diamonds (1982) and Legacy of Llylgamyn (1983). Unlike Garriott's strategy to reinvent the engine with each new game, Sir-Tech seems to have followed the old adage, "If it ain't broke, don't fix it." On a technical level, these games are practically identical to Proving Grounds, though of course they offer new stories and areas to explore.

The Knight of Diamonds involves another fetch quest, this time to find the staff of Gnilda, a powerful magical item which formerly protected the City of Llylgamyn from attack. Unfortunately, the evil Davalpus was immune to the staff's power by virtue of being born in the city (the staff's fatal flaw).

Davalpus slew the royal family except for Princess Margda and Prince Alavik, who used the staff and the armor of the Knight of Diamonds to battle the usurper. Alavik was not successful, however, and after the battle all that was left was a "smoking hole in the ground."

It's the player's mission, of course, to get back the staff, but that will mean first procuring all five pieces of the fabled armor. To complicate matters, each of these pieces is a living being that must be defeated in combat. As expected, solving the game means plunging into a dungeon (this time one with only six levels) and battling whatever beasts stand in the way.

Originally, The Knight of Diamonds required that players first complete the first game, the idea being to carry the players over into the new scenario -- an early example of an expansion pack. However, this plan didn't prove financially sound at the time, and later versions allowed players either to load a pregenerated party or to create new characters. Of course, since the dungeons are calibrated for characters of level 13 or more, new characters are very unlikely to survive their first encounter.

The final game of the original trilogy is Legacy of Llylgamyn. The goal this time is to find a dragon named L'Kbreth, whose mystical orb can save the city of Llylgamyn from the recent surge of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Characters could, again, be imported from previous games but were stripped of their experience (they are supposed to be a new generation of adventurers).

However, there is an elaborate rite of passage ceremony by which the new characters can receive a blessing from their ancestors (a boost in stats and skills). Furthermore, they can choose a new moral alignment, which determines what parts of the world they can visit. Perhaps the most intriguing innovation is that the typical dungeon crawler setup is reversed: rather than start at the top and work their way down, the party begins at the bottom of a volcano and must work its way back up.

Sir-Tech's Wizardry series earned a reputation for being difficult and addictive.

Certain traditions carry across all three games, such as Boltac's Trading Post, the Temple of Cant, and odd monsters such as Creeping Coins. Connections such as these add coherence to the series and are quite memorable for those who played the games.

Another interesting bit of lore is Wizplus, a $40 program released by a company named Datamost and released in 1982. Wizplus was one of the earliest commercial utility programs designed to allow players to freely edit their characters as they saw fit, including making them invulnerable.

Sir-Tech came out against the product, arguing that such "cheat programs" interfered with the "subtle balance" they had achieved over "four years of careful adjustment." It seems more of a testament to the game's difficulty, though, that such a product received so much attention in the first place. Sir-Tech went so far as to refuse to honor their warranty on Wizardry disks that had been tampered with using Wizplus.

Although the next game in the series, Wizardry IV: The Return of Werdna, would not be published until 1987, it's similar enough to the first three to merit discussion here. Four years had passed since Legacy of Llylgamyn, and when the game finally arrived, it no doubt took most fans of the series by surprise -- this time, the player gets to be the evil wizard hell-bent on getting his revenge.

The plot is perhaps the only one of its type in the history of CRPGs. In this game's narrative, Werdna (the wizard defeated in the first Wizardry) has awakened, but he's now without his powers and trapped in the bottom of his ten-level dungeon.

Furthermore, all of the monsters and traps that existed to keep out wily adventurers now serve the opposite purpose -- to keep Werdna imprisoned. Getting Werdna out of the dungeon will take time and patience, but the revenge will no doubt be sweet. Thankfully, Werdna is able to summon monsters to help him out, though the players are unable to control them directly.

The Return of Werdna is widely considered to be the most difficult CRPG ever created, and it's definitely a game suited only for veterans of the first three games. The dungeon is resistant to mapping, and there are several brain-stumping puzzles sprinkled throughout.

To make matters worse, the ghost of one of Werdna's slain enemies, Trebor, haunts the dungeon and will instantly kill Werdna if he stumbles upon him. Finally, every save of the game resurrects all the monsters on the current level. Rumors of this game's difficulty have not been exaggerated!

There's also a nice bit of history here that's not often discussed in modern reviews of this game: Sir-Tech used some of the characters from disks it had received from gamers, who either wanted them repaired or sent them to show they had indeed solved the game. The company used some of these purloined characters as do-gooder enemies for Werdna. The game also features three separate endings, the most difficult of which entitles players to the hallowed rank of Wizardry Grand Master.

The first three Wizardry games were quite successful and were eventually ported to the Commodore 64, DOS, and even the NES platform (which features the best graphics). Sir-Tech has published them in a various compilations, starting with the Wizardry Trilogy in 1987 for DOS. The latest publication is The Ultimate Wizardry Archives (1998) for DOS and Windows, which includes the first seven games in the series.

The fourth game is perhaps the least known, since its graphics and audiovisuals were hardly competitive for its release date, and its difficulty level ensured that no one but hardcore fans of the original games could complete it.

Though we'll have opportunities to discuss Wizardry in later chapters, what's important to note here is that Ultima wasn't the only game in town. The Wizardry series was tremendously successful.

Furthermore, Wizardry has been highly influential, even for Garriott (who, as you'll remember, acknowledged that his decision to make Ultima III a party-based game was in response to the popularity of Wizardry). Finally, it's a useful game to have in mind when discussing issues still pertinent to modern CRPGs, such as whether it's better for sequels to allow players to import their characters from previous games or to require players to start from scratch.

Gamers wanting to play these Wizardry games today have few options. If you happen to speak Japanese, you can check out Wizardry Llylgamyn Saga, a remake of the first three games available for Windows, Sony's PlayStation, and Sega's Saturn.

An effort is underway to translate this game into English. Otherwise, the only options are either to track down the old software and a system capable of running it (the NES version would probably be the best choice for this purpose) or to illegally download the games from countless abandonware sites on the web.

Although Ultima and Wizardry are by far the most popular and well- known CRPGs of the era, there are at least five other games that are either influential or innovative enough to deserve mention. These are Telengard, The Sword of Fargoal, Tunnels of Doom, Dungeons of Daggorath, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and Universe.

Perhaps the most historically interesting of these games is Daniel Lawrence's Telengard, published by Avalon Hill in 1982 for the Commodore PET (ports for other systems, including the Commodore 64, quickly followed). If nothing else, it's an enlightening study of how commercial imperatives were undermining the older mainframe policies of openness and free distribution. In the case of Telengard, this shift would result in a legal morass.

Telengard was based on a 1976 game entitled DND that Lawrence had programmed in BASIC on a PDP-10 mainframe. DND was quite a success at Purdue University, where Lawrence was a student. Later, Lawrence was invited by the engineers at DEC's factory in Maynard, Massachusetts, to port the game to the new DECSystem-20. The engineers were big fans of the game and distributed it widely.

At some point in 1978, Lawrence ported the game to the Commodore PET, implementing a clever procedure to generate dungeons on the fly. This was necessary because of the PET's extreme memory limitations (8K of RAM!). He shopped the game around at conventions, finally impressing the famous tabletop wargaming publisher, Avalon Hill, enough to secure a contract. By this time, the game had become known as Telengard, no doubt to avoid possible litigation with TSR over its trademarks and copyrights.

The publication of Telengard meant that Lawrence no longer had the desire to see the engineers at DEC freely distributing DND. After a brief period of legal wrangling, DEC had the game purged from its servers.

It's not entirely clear if the pressure to do so was coming from Lawrence, Avalon Hill, or TSR, but likely it was simply a common sense decision to avoid litigation from any of them. Unfortunately for Lawrence, DEC didn't move fast enough to keep his code from ending up in the hands of "Bill," a programmer who formed R.O. Software to distribute a $25 shareware version of DND that he released in 1984.

The game was successful enough to attract Lawrence's attention; he saw it as unfair competition and did what he could to prevent its distribution. For his part, Bill claimed that he had done enough work cleaning up the "spaghetti code" of the original game that he had in fact created a new product. In any case, Bill updated the game and rereleased it as Dungeon of the Necromancer's Domain in 1988, which he claimed was a "ground-up rewrite" in an effort to avoid future conflict with Lawrence.

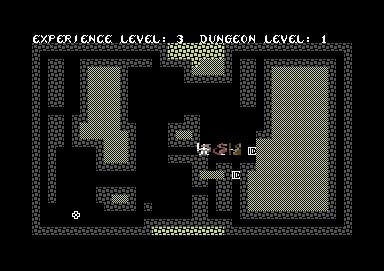

As for Telengard itself, the game introduced several innovations that were much ahead of their time. For instance, it offered procedurally generated dungeons, which essentially meant that no two games would play alike (for this reason, the game is often compared to the mainframe classic Rogue).

As for Telengard itself, the game introduced several innovations that were much ahead of their time. For instance, it offered procedurally generated dungeons, which essentially meant that no two games would play alike (for this reason, the game is often compared to the mainframe classic Rogue).

It also meant that these dungeons occupied very little of the computer's memory. This trick allowed Telengard to offer gamers "50 levels with 2 million rooms" at a time when other developers were bragging about ten. We'll see this technique in Blizzard's Diablo (1997). Telengard is also set in real-time, so that gamers taking a bathroom break might very well find their character dead upon their return.

Telengard features 20 different monster types and 36 spells, as well as fountains, thrones, altars, and teleportation cubes that produce random effects on the character. However, the game lacks a storyline; it's a pure dungeon crawler with "hack 'n slash" style gameplay. Anyone wanting to experience the game today may want to check out Travis Baldree's Telengard remake for Windows. Daniel Lawrence has also made the IBM PC version freely available from his own website.

Another early game similar to the mainframe classics is Jeff McCord's Sword of Fargoal, published by Epyx in 1982 for the Commodore VIC-20 (a significantly enhanced version followed in 1983 for the Commodore 64.)

Though McCord denies having played Telengard, his game shares many of its features, such as randomized dungeons, but differs by incorporating the quest motif: descend into the dungeon, fetch the eponymous blade, and escape. Perhaps its most visible innovation is a "fog of war" effect, which obscures parts of the overhead map until the character has explored them; it amounts to an automapping tool.

However, it's really the sound effects that set this game apart. Besides the catchy ditties that play between levels, an ominous chord progression plays whenever the monsters move in the dungeon. Players can hear the monsters without seeing them, a technique that greatly ratchets up the tension. McCord acknowledges Steven Spielberg's 1975 blockbuster Jaws as inspiration.

Sword of Fargoal has a fairly severe time limit (2,000 seconds) and is difficult to win. However, the relative simplicity of the interface makes it one of the more playable and accessible of the early CRPGs, and it was popular among gamers and critics -- indeed, it ranked on Computer Gaming World's "150 Best Games of All Time," published in 1996, and remains a fan favorite among Commodore fans.

It's recently been remade for Windows by Paul Pridham and Elias Pschernig. Jeff McCord is working with Pridham and Pschernig to release an updated version of the game for Apple's iPhone.

McCord wrote Sword of Fargoal on a Commodore PET owned by his high school in Lexington, Kentucky. It's primarily based on Gammaquest II, an unpublished dungeon crawler with randomly generated dungeons that McCord designed to show to publishers.

McCord wrote Sword of Fargoal on a Commodore PET owned by his high school in Lexington, Kentucky. It's primarily based on Gammaquest II, an unpublished dungeon crawler with randomly generated dungeons that McCord designed to show to publishers.

McCord's computer science teacher, a Mr. Syler, was fond of admonishing his class that there were to be "no games in the computer room." Nonetheless, the acerbic teacher recognized McCord's gift and loaned him a key to the lab, which he used during off- hours to program and play-test the game.

The finished project weighed in at a compact 14 kilobytes, an impressive feat given the depth of gameplay. McCord, the son of a computer science professor and an avid D&D Dungeon Master, was only 19 years old at the time. Incidentally, the title was originally to be Sword of Fargaol, based on the old spelling of jail. However, Epyx felt that few gamers would appreciate the somewhat obscure reference.

Although the game is well-known among Commodore 64 fans, it did not represent a significant financial windfall for McCord, who admits that he earned no more than $40,000 in royalties during its publication run. Nevertheless, Sword of Fargoal is, in my opinion, the best of the early CRPGs. Unfortunately, McCord's next project, Tesseract Strategy, was never completed, though its intended publisher, Electronic Arts, had expressed enough interest to fly McCord to San Francisco for a photo shoot.

The next two games we'll discuss, Dungeons of Daggorath and Tunnels of Doom, are examples of games that were released only on a single, relatively minor platform (the Tandy CoCo and Texas Instruments' TI-99/4A, respectively). Thus, we have an intriguing question of whether their success owes more to their intrinsic qualities or to the lack of direct competition. In any case, they are highly innovative games that are certainly worth our attention.

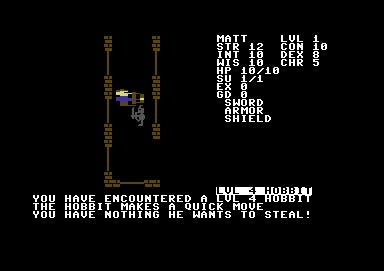

Dungeons of Daggorath, developed by DynaMicro and published by Tandy in 1982, offers a 3D, first-person perspective in wireframe of the dungeons quite similar to that seen in Akalabeth and Wizardry. The storyline is the standard "kill the evil wizard buried deep in a monster-infested dungeon." There are only five levels, a dozen creature types, four rings, and of course the usual shields, swords, scrolls, and torches (like many games of the era, players must carry a lit torch to see in the dungeons).

However, what makes Dungeons of Daggorath stand out is its real-time fatigue system. The system is represented by a pulsating heart at the bottom of the screen; it beats faster or slower depending on the level of stress the player is experiencing.

However, what makes Dungeons of Daggorath stand out is its real-time fatigue system. The system is represented by a pulsating heart at the bottom of the screen; it beats faster or slower depending on the level of stress the player is experiencing.

Taking damage or moving too quickly will cause the heart to pulse rapidly. If the heart beats too furiously, the character will faint (and likely become monster meat). This fatigue system does away with the numerical hit point or vitality systems so prevalent in other games. Instead, players must listen to the beating heart, a sound well known for its unsettling effect in horror films.

This sound effect makes for a more visceral, arcade-like experience than most CRPGs, then or now. The game was recently remade for Windows and is freely available for download.

If Dungeons of Daggorath was the big CRPG for the Tandy CoCo, Tunnels of Doom was most certainly the best CRPG going on Texas Instruments' TI-99/4A. Texas Instruments is one of the few personal computer manufacturers that actively discouraged third-party development, preferring to publish all software for their systems themselves.

Rather than generate a collection of must-have exclusives that would help sell the platform, the policy disenfranchised developers and no doubt proved disastrous for Texas Instruments. The inevitable result is that the TI-99/4A had one of the smallest game libraries in the industry; only 40 or so games were ever published for it, the bulk being remakes of popular arcade games.

Nevertheless, at least one gem really stands out. Programmed by Kevin Kenney and published by Texas Instruments in 1982, Tunnels of Doom contains many of the features that will show up in later games such as SSI's "Gold Box" games, which debut in 1988 with The Pool of Radiance.

Perhaps the best way to describe the game is as a combination of themes from Telengard and Wizardry. Like Telengard, Tunnels of Doom features fountains, altars, and thrones that have random effects on players willing to experiment with them. However, the game imitates Wizardry by allowing the player control a party of adventurers (four, to be precise) rather than a single character.

It also predates Ultima III in offering different screens for combat and exploration, as well as in using solid colors for the first-person, 3D dungeons rather than monochrome wireframe graphics. It even offers an automapper!

Like Ultima III and the later "Gold Box" games, Tunnels of Doom switches to a top-down, tactical screen whenever the party engages in combat. Combat is turn-based and offers ranged as well as hand-to-hand weapons.

Another nice touch is the ability to target specific monsters with ranged weapons, rather than just firing them in a straight line. Although there are only three classes available (fighter, wizard, and rogue), a special hero class was available to players who opted to lead a single adventurer in the randomly-generated, ten-level maze. All in all, it's an intelligent system that was relatively easy to learn and quite flexible.

The game shipped with two adventures: "Pennies and Prizes" and "Quest for the King." The first of these was more or less a tutorial designed to familiarize users with the interface (or to entertain small children). "Quest of the King" is the standard "fetch the orb" quest, though players must also locate the king and return him and the orb to the surface. A strict time limit ratchets up the tension.

The game shipped with two adventures: "Pennies and Prizes" and "Quest for the King." The first of these was more or less a tutorial designed to familiarize users with the interface (or to entertain small children). "Quest of the King" is the standard "fetch the orb" quest, though players must also locate the king and return him and the orb to the surface. A strict time limit ratchets up the tension.

However, what most people remember about Tunnels of Doom are the many third-party modules created with Asgard Software's Tunnels of Doom Editor, created by a Chicago police officer named John Behnke. Fans of the game would often design their own scenarios and distribute them at conventions and club meetings, and a few were even available commercially in compilations sold by Asgard. One of the more unusual of these is a game where the dungeon is a K-Mart store. Another was based on the popular TV show Star Trek, though I doubt seriously whether this scenario was authorized by Paramount.

Although the game was one of the most successful for the TI-99/4A, Texas Instruments laid off Kenney shortly after its release. Kenney speculated in a 2002 interview that the company was unhappy with his "liberal political bent," but TI later contracted him to do some additional databases for the game (they were never released).

Many of the games we've talked about so far have been assigned to one player, and the few exceptions were online games. Arguably, most party-based CRPGs can be played with a group simply by assigning each player a character; the person behind the keyboard takes the players' orders and acts accordingly (in theory). Indeed, some early manuals hint at exactly this kind of gameplay. However, two early CRPGs written by Stuart Smith for Quality Software integrated cooperative multiplayer options into the interface.

The first of these games was Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, published in 1982 for the Atari 400 and 800 and the Apple II. As the title suggests, the game is based loosely on the old Arabic stories from The Book of One Thousand and One Nights, which makes a pleasant departure from the conventional high fantasy motif, though a quest to rescue a Sultan's kidnapped daughter is hardly extraordinary.

While relatively simple compared to games like Ultima and Wizardry, the game stands out because of its dynamic multiplayer options. New players can be added at any point during the adventure, and they are allowed to roam about the dungeons independently of the main character, Ali Baba. Ostensibly, gameplay would have been arranged in the "hot seat" fashion, where players either took turns behind the keyboard or simply handed their joystick or paddle to the next player.

The game was reasonably successful, and Smith soon created a very similar game called Return of Heracles (sometimes Herakles), based on the famous Greek stories retold by Robert Graves. This time, gameplay is structured around the fulfillment of twelve tasks, mostly involving slaying beasts, fetching items, or rescuing damsels in distress.

Again, the most innovative aspect of the game is the cooperative multiplayer options, though critics made note of the 250 different types of creatures and intuitive gameplay. Critics did complain that the game didn't follow the Greek legends closely enough, and there are plenty of anachronisms, such as the use of iron and steel during what is ostensibly the Bronze Age (if not earlier). Apparently, even Doctor Who, the character from the famous British television show, makes an appearance!

Ali-Baba and the Forty Thieves allows players to control multiple characters, who can act and move independently.

Both games were updated and repackaged in 1986 as Age of Adventure, published by Electronic Arts for the Apple II, Atari 400 and 800, and the Commodore 64. Reviews were generally positive, though the graphics certainly looked quite dated. Stuart Smith would gain far more notoriety for his Adventure Construction Set, published by Electronic Arts in 1985 for the Apple II and later for a variety of platforms.

The highly successful program made it easy for CRPG fans to create their own tile- based, Ultima-style CRPGs and adventure games, and included two scenarios. One of these was "Rivers of Light," based on the legend of Gilgamesh, the hero of Sumerian mythology. Again we see Smith's preference for ancient mythology over the standard swords and sorcery theme. We'll have more to say about this program and others like it later in the book.

William Leslie and Thomas Carbone's Universe game, published in 1983 for the Atari 400/800 and later for the Apple II, is reminiscent of Edu-Ware's Space and Empire series that we discussed in the previous chapter. It's a very interesting game for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the rather shocking retail price of $89.96, which adjusts to $181.18 in 2006 dollars. The game shipped with a 75-page manual encased in a three-ring binder, as well as four floppy diskettes (a record at the time).

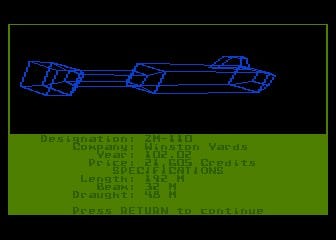

Like Space and Empire, Universe is a futuristic CRPG that has players flying spaceships rather than slaying dragons. The game is set in the Local Cluster, a galaxy colonized by Earth but now apparently abandoned by the motherworld. Chaos is beginning to take hold in the outlying sectors, and piracy is threatening to disrupt trade and fling the galaxy into barbarism.

In the midst of the crisis, rumors surface of a Hyperspace Booster, which, if found, could reunite the Local Cluster with the Milky Way. However, players are given considerable leeway in achieving this goal. For instance, they might opt to become merchant traders, shipping cargo back and forth among the 21 star systems of the Local Cluster. Or they might take to mining, touching down on mineral-rich planets in a search for the mother lode. Finally, they might opt to become pirates themselves, earning rich rewards at the expense of civilization.

Technically speaking, it might be a stretch to define this game as a CRPG, since there is little in the way of character development. Although players must hire a crew, they are represented almost entirely by number and do not benefit from experience. However, players can turn their earnings into upgrades for their ship, making it more efficient or effective in combat.

During this history, we'll encounter several of these space simulator/CRPG hybrids that resist easy classification. Typically, they are characterized as open-ended games and usually feature action-based combat in the style of a flight simulator, albeit with zero-G physics.

Certainly, games such as Accolade's SunDog: Frozen Legacy (1984), Firebird's Elite (1985), and Origin's Wing Commander: Privateer (1993) spring to mind. However, we'll be discussing such games only if the CRPG element, such as a class/level system for the captain or crew members, is featured more prominently than the simulator-style action sequences.

Certainly, games such as Accolade's SunDog: Frozen Legacy (1984), Firebird's Elite (1985), and Origin's Wing Commander: Privateer (1993) spring to mind. However, we'll be discussing such games only if the CRPG element, such as a class/level system for the captain or crew members, is featured more prominently than the simulator-style action sequences.

Universe II, released in 1985, introduces precisely such role-playing elements. Now, the crew has individual names, grades, and skill types: astrogator, pilot, marine, miner, and gunner. The combat that takes place when a crew boards another ship is now more tactical and closer to combat in contemporary CRPGs.

Unfortunately, the game seems to have been striving to be a jack of all trades; it incorporated a lengthy text adventure sequence with a very limited parser. This segment was panned in reviews, and that, in addition to the again-hefty price (this time $69.95, or $130.88 in 2006 dollars) may explain its almost total obscurity today.

Nevertheless, Omnitrend published yet another sequel, Universe III, in 1989, though this game is most decidedly an adventure rather than a CRPG. Omnitrend would gain more fame in the 1990s for its Breach line of futuristic, turn-based strategy games, some of which contain minor role-playing elements.

Although there were certainly some ambitious and exemplary games produced between 1980 and 1983, everyone knew the best was yet to come as computer hardware advanced and programmers continued to refine their skills. On the other hand, we can also say that, by 1983, almost all of the conventions we'll see in later CRPGs had been established or at least demonstrated.

From this point forward, we will be able to describe most CRPGs as combinations of elements from Silver Age games. What is The Pool of Radiance but Tunnels of Doom meets Wizardry? What is Diablo but Telengard with better audiovisuals? How far have we really come from pedit5, dnd, and Moria? It's impossible to truly appreciate or understand these later games without at least some knowledge of the groundbreaking CRPGs that came before them.

Nevertheless, there's a reason I chose to call this period the Silver and not the Golden Age of CRPGs. After all, some of the games we've discussed in this chapter (particularly Ultima III) remain fan favorites and, at least in fans' opinions, have never been surpassed or even equaled.

While I certainly agree that these games were innovative and even formative, I still view them more as prototypes: experimental CRPGs designed at a time when developers were still struggling to find their way. The genre simply needed time to mature.

Hopefully, you'll agree when we begin our discussion of classics like Phantasie, The Bard's Tale, Might and Magic, Dungeon Master, and Wasteland, as well as SSI's celebrated "Gold Box" and "Black Box" games. What we'll see happening between 1985 and 1993 is an explosion of innovation and diversity, with hundreds of titles and a great deal of experimentation.

Although many of the triumphs will be in the realm of graphics and sound, others have more to do with the art of storytelling, world building, and character development. We'll also see developers struggling to stay ahead of the latest advances in hardware, for we'll soon see how graphical considerations rise in prominence and, at leastfor some gamers, eventually trump all else.

[Want more? Check out the original series of pieces Barton wrote for Gamasutra in 2007, which can be found here: The Early Years, The Golden Age, and The Platinum and Modern Ages.]

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like