Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What's the big deal with Jesse Schell's new 'Art Of Game Design' book? Writer and designer Daniel Cook takes a look at the Front Line Award winning tome.

[What's the big deal with Jesse Schell's new 'Art Of Game Design' book? Writer and designer Daniel Cook takes a look at the Front Line Award-winning tome to find out.]

Over my holiday vacation I finished reading The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses by Jesse Schell. Schell teaches game design over at Carnegie Mellon and works in the industry leading Pittsburgh-based Schell Games (Toy Story Midway Mania!), and he has produced a comprehensive and clearly written book mapping out the conceptual tools and techniques of game design.

The book is targeted at the new game designer, but seeks to provide enough depth to be broadly useful to working designers.

It perhaps goes without saying that this is a book on game design, not game development. It will not teach you about programming, art or much of any technical production skills. It is about game mechanics, the player experience, pitching, iterating, and brainstorming; all the messy core activities of game design.

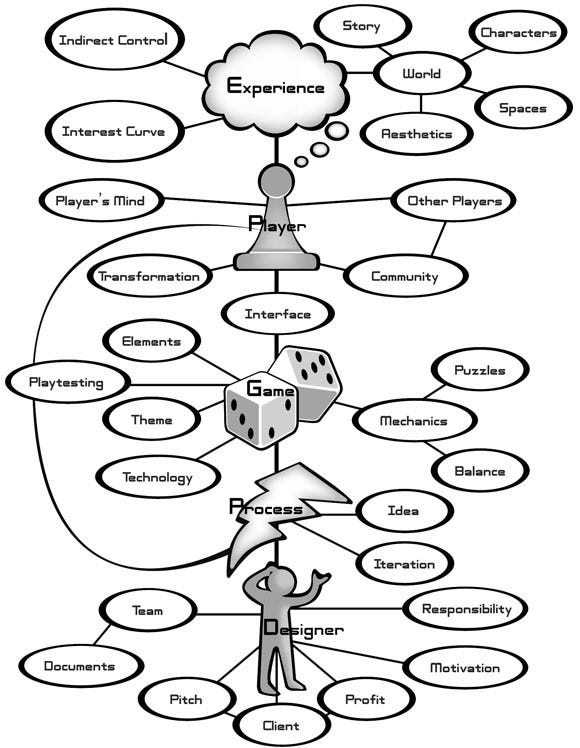

The book has two organizing principles. The first is an organically laid out map of all the important elements of a game design. This allows you to deconstruct a game and gives names to what you are talking about.

The second is a series of "lenses", or questions, that you can ask about your game design as you iterate upon it. It is a good book that teaches the craft of game design in an accessible manner.

An excavated ant colony from the documentary Ants: Nature's Secret Power

An excavated ant colony from the documentary Ants: Nature's Secret Power

Once I saw a video where they poured cement into an ant colony and then carefully excavated the resulting organic structure. Bit by bit an intricate city of interconnecting rooms and passages was revealed.

For some odd reason, this is the exact image that comes to mind as Schell methodically builds out an elegant yet comprehensive map of game design.

Schell's map of the game design process

Schell's map of the game design process

The book builds up the basics of game design one simple piece at a time. It starts with the rules and tokens of the game, flits through game mechanics, economics and community and ends with discussion of teams, clients and pitches.

Over the past few decades, modern game design has accumulated numerous little rooms and offshoots. It is a rare treat to see it laid bare in all its organically evolved glory.

Each chapter covers a statement about games (such as "Game mechanics must be in Balance") and spends 10 to 40 pages digging into exactly what that means. The text goes just deep enough to give you practical insight into how the key concepts might be useful without becoming wordy. If you only had a vague understanding of what goes into a competent interest curve when pacing your gameplay, you'll come away with some good tools on how you might improve pacing on your current design.

From Lens #61: The Lens of the Interest Curve. An illustration of a fractal interest curve.

From Lens #61: The Lens of the Interest Curve. An illustration of a fractal interest curve.

Many concepts are illustrated with practical examples from Schell's time at Disney working on projects like Pirates of the Caribbean: Battle for Buccaneer Gold.

The very readable text doesn't assume that you know a lot about games and manages to define most terms using common language without coming across as condescending. If you are looking for a competent introduction to game design, this book is a good place to start.

In the process of mapping out game design, Schell does a great service to the community by collecting the many common terms of game design all into one tidy chart. The crisp definitions of foundational concepts are written at a level applicable across a vast range of genres and platforms.

For example, he defines a puzzle as a "game with a dominant strategy" and makes the observation that puzzles aren't so different than games, except for the fact that once you figure out the optimal way of playing a puzzle, they tend to lose all replayability.

His descriptions of puzzle design work just as well for the next crossword compilation as they do for an indie title like You Have to Burn the Rope.

Clear, practical language is an evergreen addition to our industry's working knowledge. Schell's terminology works for board games, video games and I suspect it will still be useful when we talk about virtual worlds and whatever else games evolve into in the future.

In the work place, a lack of shared vocabulary is the bane of rapid problem solving and I would be delighted to see some of the definitions in this book more widely adopted.

Though the elements of game design are well described, practicing designers won't find a lot of new insights that haven't been covered elsewhere. Luckily, the book also includes some more utilitarian tools in the form of 100 "lenses", or questions that help you iterate on your current design.

A designer's job often consists of asking questions. Almost as soon as you start building a game, you need to ask "what should be improved?" There are nearly an infinite number of questions one could ask and often finding the right question to ask is key to coming up with the right solution.

The 100 Lenses are a set of time-tested questions that you can ask about your game. Are you using your elements elegantly? Could your pacing be made a bit more interesting by using interest curves? What is the balance of long term and short term goals for the player? One of my favorites is Lens #69, The Lens of the Weirdest Thing:

"Having weird things in your story can help give meaning to unusual game mechanics -- it can capture the interest of the player, and it can make your world seem special. Too many things that are too weird, though, will render your story puzzling and inaccessible. To make sure your story is the good kind of weird, ask yourself these questions:

What's the weirdest thing in my story?

How can I make sure that the weirdest thing doesn't confuse or alienate the player?

If there are multiple weird things, should I maybe get rid of, or coalesce some of them?

If there is nothing weird in my story, is the story still interesting?"

These are the sort of questions that get me looking at my game designs from a new perspective and can really jolt the creative juices. Not all of the questions will be useful.

However, somewhere in the list are at least two or three questions that even the most experienced designer wished they had asked sooner. By having the questions at your fingertips, you can ask them earlier.

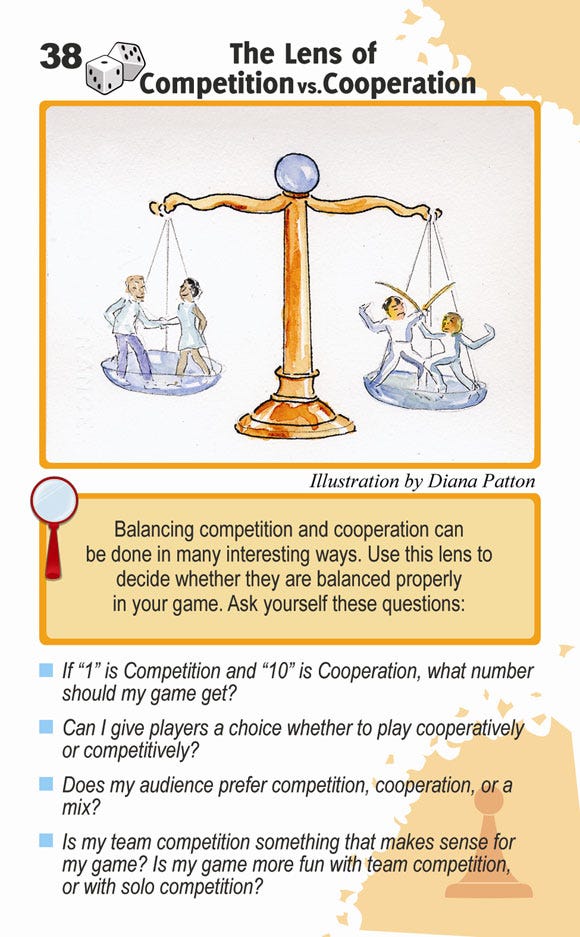

Lens 38: The Lens of Competition vs Cooperation from The Art of Game Design: A Desk of Lenses

Lens 38: The Lens of Competition vs Cooperation from The Art of Game Design: A Desk of Lenses

Schell has made accessing his lists of useful question even easier. A companion piece to the book is a 100-card deck based on the lenses described in the book. Each card contains a memorable image and a set of questions you can ask about your design.

These cards are meant to be used in a fashion similar to other popular brainstorming cards such as IDEO Method cards or Brian Eno's Oblique Strategies deck.

You keep them close at hand and when you are need a bit of inspiration; you flip through a few and see if any catch your eye.

There is a wonderful field of research called distributed cognition that starts off with the concept that even smart people can only keep a few things floating in their head at once.

If pressed, most "experts" are only able to list 20 to 30% of the major factors involved in any process off the top of their heads. They think that they've only missed a handful of issues when in fact they've missed 70% of the items they should be considering.

Distributed cognition then takes the next step and explores how we can improve our problem solving abilities by offloading concepts into our environment.

When you see a team working productively in a room full of whiteboard drawings, you are witnessing distributed cognition. By offloading a brilliant idea onto a whiteboard, you make room in your limited gray matter to think up a new idea.

Game design has become so broad that it is nearly impossible for a single person to keep all the concepts in their head at once. We miss asking many of the basic questions on a regular basis.

The Deck of Lenses is one way of giving us a helping hand. By putting the Lenses in a portable, tactile format that can be split, shuffled, glanced at and passed around a group, the content becomes dramatically more useful than if it was locked up on a thick book languishing on a shelf.

I've gotten into the following fruitful habit. During a quiet moment, I take the deck and sort it into two piles:

The cards that are pertinent to the game at hand are put into a "keeper" pile.

The cards that are either a bit too esoteric or not applicable, I put into a "discard" pile.

Periodically, I shuffle through the keeper cards and see if I can answer the questions that pop up. When I have good answers for most of the questions, I have a warm feeling that the design is on track.

When the answers are fuzzy, I'm often prompted to think about an aspect of the design that was previously being ignored. Mix in a few note cards with your own project specific questions and you have a useful touchstone that can be shared with others on the team.

I suspect this exercise won't work for every designer, but it is nice to see that such a practical game design tool available on the market.

I enjoyed the book quite a bit, but as always, there are a few areas that could use improvement. First, as a minor quibble, the cards occasionally reference lists buried deep within the book. This makes them slightly harder to use than if each card was completely self-contained.

Secondly, the book has only a few pages on the business aspects of game design and it focuses almost exclusively on the dynamics of a typical retail title. While much of the content in the book will stand the test of time, I suspect this section will age poorly.

Business models are changing rapidly with many upcoming games focusing on downloadable content, subscription models, advertising, microtransactions, free-to-play and more.

More importantly, much of modern game design is now intricately intertwined with the process of making money. If games have any ability to influence and change behavior, and I very strongly believe that they do, those powers will be used first and foremost, not for art, but for capitalist gain.

Any book that seeks to be a general education for game designers might want to make note of how the extraction of money from players has a major influence on how they structure their design.

My last concern is less a problem with this book and more an observation about the maturing state of game design. When books on game design first started appearing (such as Chris Crawford's seminal The Art of Computer Game Design), they were the works of wild-eyed explorers fearlessly blazing new paths through the untamed wilderness of a vibrant new field.

In contrast, Schell has written a solid survey of the craft of game design as it has evolved over decades of practice. You'll find the required mention of flow, a discussion of transmedia, and even a nod to the innovator's dilemma.

There is a great smattering of proven techniques, some lovely jaunts into the major factors that influence your design, but no bright new paradigm that will illuminate how you see games.

The closest the book gets to a grand vision for game design is the importance of the "Loop", the iterative process of building, playing, analyzing and improving that all great games undergo. This is fundamental stuff, but in general the book's value remains in the wisdom of a hundred details as opposed to a big unifying idea or philosophy.

We are left with a craftsman's book, not a book of unifying artistic vision. Such a thing is still quite valuable. The world always seems to have more craftsmen looking for their next conceptual hammer than it has artists needing a vision.

Of course you should pick up a copy. It is a quick read and the concepts are solid. If you are a student, it is perhaps the most comprehensive and crisply written intro to the key elements of game design that I have read. If you are a practicing designer, you may want to also grab the companion cards as well.

Now that game design has a hundred facets, there is no way anyone can keep all the various mental tools in their head all at once. The act of flipping casually through a few cards is a wonderfully tactile method of jolting one's creativity.

In my library of game design books, I see The Art of Game Design as the common designer's pragmatic companion to a theoretical tome like Salen and Zimmerman's Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals.

Both uncover the vast hidden anthill that is game design. Both describe dozens of ideas and tools a game designer should master. Both seek to provide a roof for all perspectives, no matter how divergent. Of the two, The Art of Game Design is considerably more approachable, with the trade off of being a lighter, and slightly less thought provoking read.

After putting the book down, I was struck by the unexpected feeling of jealousy mixed with delight. What a wonderful thing it is that bright-eyed young designers are able to live in a time when such hard fought wisdom is readily available in such a clear and digestible form.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like