Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

This three-part series will cover three aspects of creative leadership, i.e. that messy head-space where lead designer meets producer, starting with creative direction as internal pitching.

This blog post was written by Tanya X. Short, the Captain of Kitfox Games, a small independent games studio in Montreal currently working on Boyfriend Dungeon and publishing Six Ages and Dwarf Fortress.

This is the 3rd and final part of a series. Part 1 introduced the idea of creative management practice as pitching to your team. Part 2 described how to assess your personal strengths and weaknesses as a creative director.

Let’s pretend a team-member shows you something in your game, and asks for your feedback. You can see right away something that’s wrong.

What do you say?

Worst: “Make this button right here blue. In fact, let me do it for you.”

Bad: “Make the interface more blue.”

Better: “Don’t you think a more blue interface would feel more professional?”

Best: “We want the game to feel cold and professional. I think the interface isn’t achieving that right now. How do you want to address that?”

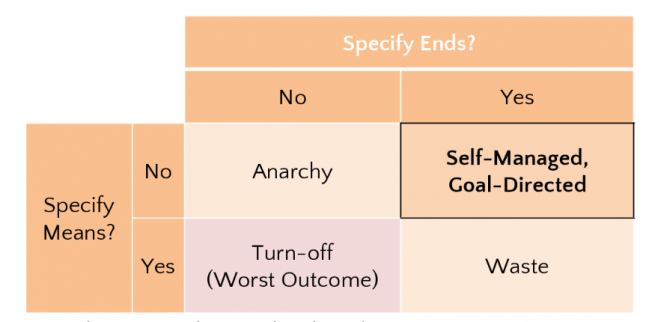

Compelling direction specifies the ends but not the means.

Why? Because as the director, your job is to bring out the best in your team, which means allowing them to be both self-managed yet also goal-oriented, which is the ultimate in both efficiency and motivation.

From Leading Teams by J. Richard Hackman

Telling people HOW to do their job de-motivates them, but telling them WHY they should want to do it (i.e. pitching, from part 1) but also what their goal is in their work is invigorating.

Think about it: have you ever enjoyed your boss telling you how to do your job? Even if they’re more experienced at your exact job, the answer is no.

For example, in Boyfriend Dungeon, telling the combat designer that I think the dagger attack time should be 0.1s shorter might be overstepping, even if I think it’s obvious. However, saying something like “the goal is for each weapon to feel distinct from one another, and saying the dagger currently feels very similar to the Talwar”, lets her make her own decisions about how to move closer to that goal. Maybe she’ll shorten the attack time, maybe she won’t, but it lets her put her problem solving skills to use.

The obvious danger in communicating ends without means is that the team-mate almost certainly won’t implement the solution that you would.Unless you happen to be extremely in-tune, they will have their own ideas, their own approach, and will pursue the goal you set in their own way. But… that’s not just okay and valid. That’s value. You have to accept that, up-front, or else this will all collapse on you later as your team comes to realize they need to read your mind in order to get approval.

Remember that first example with the blue button? If actually what you want is a blue button then sure, go for it, tell them that’s what you want. Just know that it comes at the cost of your team’s motivation.

But if what you want is a better game, made more efficiently, by a happier team, you’ll realize the blue button is just one way to achieve the effect you want, and maybe your team will come up with an even better solution that you haven’t thought of.

Last time, I suggested a few possible strengths, such as Ambition, Energy, Consistency, Collaboration, Clarity, and Decisiveness. (If you want a refresher on what I mean when I use these terms, see Part 2.)

But how do you use these?

If you want your team to be..

Motivated then your direction should be Challenging

Focused then your direction should be Clear

Productive then your direction should be Meaningful

“Challenging”, “clear”, and “meaningful” as the three aspects of good direction is again taken from Leading Teams by J. Richard Hackman.

Challenging direction energizes the team and encourages growth.

Ambitious creative leaders tend to create a loyal following, both from fans and team-mates, even if they have other weaknesses, because challenging direction is motivating. As humans, we love to be challenged and grow in our expertise. Especially when you’re dealing with curious, technical people like game developers, complacency is the enemy of motivation.

It can be helpful to analyze the direction you’re giving from the angle of “how does this project help this team member grow?” If you can’t answer that question, don’t be surprised to see their motivation drop throughout the course of the project. In fact, it’s probably worthwhile to find a new aspect of the project for them to work on, just to re-engage them.

When in doubt, especially at the beginning, set the project goals just a bit further than the team’s current capabilities. And whenever the schedule allows, push them to make their work even better. Always strive for improvement.

If you find your challenges aren’t having a positive effect, it’s possible you’ve set the bar unrealistically high, or your team doesn’t believe they can achieve what you want. Or.. it’s possible your chosen direction (and all of its tasty challenges) aren’t being clearly communicated.

However, there’s no point in your direction being challenging if nobody knows what you mean. Here is where clarity, consistency and decisiveness come in.

Clear direction orients the team and aligns them with your purpose.

In an ideal world, you would have a telepathic link with your team members, and they would see exactly the vision you have in your head. Unfortunately, most of us have to make do with tools, which I’ve listed here in ascending helpfulness:

Spoken Word: Personal explanations. The most natural way to give direction, it is also the most ephemeral and forgettable. If you’re having too many meetings, maybe you should document more.

Written Word: Descriptions, bullet points, documents, and wikis. I love them, but they take work to digest, and language can be deliciously ambiguous. Plus, your team might have non-native speakers. Don’t hold them back with your method of communication.

Diagram: Now we’re getting somewhere. An explanatory visual such as a flow-chart or even a doodle can sometimes intuitively explain a complex process in instants.

Illustration: Images can be wildly informative in a visual medium like games, such as a mocked-up screenshot of the kind of gameplay you’re envisioning. Usually worth at least a thousand words, if not more.

Video: Better than a mocked up still image is (even a very short) video of the gameplay you’re envisioning. Our brains extrapolate an incredible amount from even a few frames of moving images. For the highest-density communication, you can’t beat a video, even the lowly gif.

I actually learned this by accident when leading Moon Hunters. As part of the Kickstarter video, we mocked up some gameplay to show the features to players — travel, combat, menus, etc. It was only intended as a marketing piece. But later, when discussing certain feature designs, we would refer back to the video, and use it to evaluate our progress. Even though I had written tons of documentation on our wiki (much of which was used during implementation), the quickest and best reference remained this video.

I’ve heard Ubisoft internally calls these “fake” gameplay videos Vision Documents, and uses them as part of their official project greenlight process, and it makes total sense to me. Sure, you can repurpose them as E3 videos I guess (if you’re willing to take a few, uh, risks), but even just as a way to Focus the team, such a video remains magical, giving them very clear direction in what the game looks, sounds, and feels like.

Meaningful direction engages the team personally and maximizes their output.

In some ways this is the easy one — most game developers already love games! Game developer qualifies as a dream job for many young people. So the basic “meaningfulness” of game dev work defaults to a higher level than your average office worker. However, we’re not saving lives. We’re “just” making games. Sometimes that isn’t enough on its own.

If you find a team member’s work is falling behind without explanation, maybe look at whether their work feels personally meaningful to them. But whereas finding something challenging for each person can be semi-predictable(probably your artists would like their art tasks to be challenging), meaning is very personal and idiosyncratic. Some people for example just really love cats, and if your game includes cats, they will instantly be more attached to the project and invested in its quality.

Common meaning found in games and other commercial art:

Entertainment value: A good catch-all many games fall back on instinctively is pointing to the enjoyment of the players, regardless of genre or platform. It’s easier to feel good about your work when you see how much other humans enjoy it.

Courageous cultural leadership: If the content of your game aligns with your team’s political or social values, and makes them feel they have a voice, they are more likely to feel their contribution to that statement is meaningful.

Aesthetic: If the look, feel, or style of your game is particularly appealing to your team’s taste, they are more likely to find it meaningful to complete.

Prestige: If the game can be said to be ‘best-in-class’, or win awards from respected colleagues, your team is more likely to feel the project they contributed to was meaningful.

It’s worth noting that for some types of particularly mastery-driven people, the challenge of the work is in itself the meaning, for them. I’ve found this to be particularly true for tools programmers, network programmers, and data analysts, who need no validation from the game’s audience at all. It’s possible that redoubling your commitment to challenging these folks is enough and they don’t need ancillary meaning.

Six strengths of a great creative leader

Again, these are just the six leadership strengths that speak to me personally. Come up with your own, if you like! But here are some tips for how I try to work on them and improve them.

Decisiveness: Be faster. “Allow yourself to make mistakes, at least as often as a committee — if you’re faster, you’re winning” — Randy Smith.

Energy: Get excitable and optimistic. Hunt for new sources of inspiration and share them. “Be your team’s cheerleader” — Sandy Peterson.

Ambition: Get fresh eyes on the project. Play competitors. Take a step back. Maybe you’re too deep in the weeds to see what’s truly broken — or how the thing you are obsessed with is actually not a big deal.

Clarity: Communicate more, and in new ways — visually, ideally, and in a way that can be referenced later.

Consistency: Define your audience more specifically (through psychographics, for example), including who will dislike your game. Reference that audience instead of your personal gut.

Collaboration: Have clear decision-making processes. Build relationships of trust and emotional stability. Lower the stakes of offering critiques and new ideas. “Be honest but hopeful.” — Jill Murray

Creative direction is a soft skill, best judged by the people you work with. But like any other skill, it can only be improved through practice and reflection.

May the direction you give your team be increasingly challenging, clear, and meaningful. Here’s to a happier team, making better and better games.

This is the 3rd and final part of a series. Part 1 introduced the idea of creative management practice as pitching to your team. Part 2 described how to assess your personal strengths and weaknesses as a creative director.

You May Also Like