Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The Braid developer has recently revealed his next title, The Witness, and talks to us about the design of this game in detail, also diving into the ethics of game design and other issues indie and mainstream developers face.

Jonathan Blow went from well-known within the development community to a rising star of the new indie movement when his Xbox Live Arcade, PC, and PlayStation network title Braid became one of the biggest successes of the nascent download space -- particularly on Xbox 360.

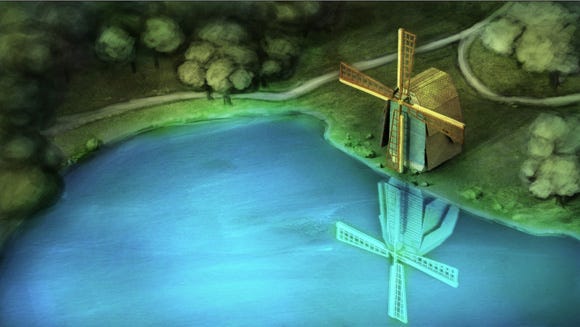

Since then, everyone has been waiting to see what his next title will be. Recently, he announced and began to demo The Witness, a 3D adventure game. While the shift from Braid's 2D platforming style was somewhat surprising, there are similarities -- and in this interview, given at the recent Nottingham GameCity event, Blow discusses both the subtle and obvious ties the new game has to his previous hit.

He also deeply discusses the ethics of game design, picking apart what he believes developers should and shouldn't do and why, what Microsoft forces him to do that he wishes it would not, and much, much more.

We haven't spoken for a couple of years.

JB: Last time we talked it was two days before Braid was released or something.

Or one day. So I didn't know how that was going to go, and fortunately it went really well; you know, people liked the game and it review well, sold well.

After that, I kind of took a bit of a break from serious development and prototyped some different ideas. Like... there were games that I spent two or three months on each, just playing around with.

They were good, interesting ideas, and the one that I liked the most... you know, that I didn't want to do at first because it was a very ambitious and challenging game is what I'm actually working on now, this game that we've revealed today.

Well, I've been working on it seriously for about a year with a small team of people. I started hiring those people on to work on the game almost exactly a year ago.

What kind of roles have you hired?

JB: There's a full time 3D artist and there's a full time tech programmer. And then, I did a bunch of tech programming early on just to get the engine together so we could kind of run the game.

Now, I'm mostly focused on game design and also on gameplay programming because as a designer it's easier to get things done if you just type it in. But most of the programming we've doing is like, "I want this certain object that behaves in a certain way", right? Whereas before it was like, "I need the shadows all over the world to be like accurate."

So you've recruited so you can do the stuff that you want to focus on.

JB: Yeah, because tech programming is really... It takes a lot of time and energy. It's very absorbing and it's hard to do game design while I'm doing that.

So are you working remotely or are you working together?

JB: We're a distributed team right now, which has advantages and disadvantages. I think that, eventually, we're going to get an office and maybe move in a couple days a week. But right now, people live far enough apart. And aside from those two other main people that I talked about... so we're the only three that are working on the game full-time, but there's a number of people who are contributing in a part time, looser kind of way. And they live even more discriminately.

Have you found people you've worked with previously, or did you advertise?

JB: Well, [Braid art director] David Hellman is doing some stuff. He's doing some conceptualization and advanced thinking about what certain parts of the environment should look like, you know, how to make things interesting.

Other people who haven't worked with me on a game before but -- there's audio work being done, there's concept art. We're in the process of hiring our architect to do design for the buildings, because we care a lot about what those spaces feel like to be inside and architects are very good at helping to channel that kind of thing.

And also, each location is going to have its own visual style as well as puzzle style and just making it cohere. So there are a bunch of roles like that. Like there was no role for an architect in Braid, so it's a little different now.

So were you certain that you wanted to do a 3D title?

JB: I absolutely didn't want to do a 3D title. You know, after you do a game and it's commercially successful and you have money and you can go and do whatever you want, the biggest mistake is to do what people often do -- a super ambitious second project that is very expensive and uses all of your money, and you don't get it done, or it flops, or whatever, and then you're poor and you're back to square one, right?

I didn't want to do that, but this is exactly that kind of game. It's 3D, it's much harder to make, it's sprawling, it's bigger than Braid, it's a longer play experience.

However, I look at these other prototypes that I did which would've been easier games to make, and I just felt so much more excited about the concept behind The Witness and I felt it was more important to do that game than the other ones right now.

So I just said, "You know what? It's risky, it's gonna take a long time to make this game, it's gonna be very difficult to make it as compelling as a traditional game is because it's so weird, but it's what I really want to do." So I did that.

And why did you really want to do it?

JB: Well, it's hard to explain, because it has to do with something that I don't want to spoil. The game is about certain kinds of magic moments that happen in the mind of the player.

So actually it's interesting... back before I did Braid, for a long time I was an independent developer and I would do little projects. And one of the projects that I talked previously about in the public I never ended up finishing it; it had some interesting game design ideas, but I kind of dropped it because it was too hard, it was kind of unplayable. But that game had like a kind of a magic moment in it that wasn't part of the main gameplay, but it was like a side thing that I thought would be really cool.

And after finishing Braid -- actually just before finishing Braid, when I needed a break from all the console certification stuff -- I just thought about some of these old games, because I was thinking, "What do I want to do next?".

And I thought about this game and I was like, "You know, I still don't know how to make the gameplay of that work. But this magic moment here is really exciting and cool." And as soon as I focused just on that, and I thought, "Why don't I throw away the rest of that old game that doesn't work and just build an entire new game around this kind of heart of an idea?"

So I ended up doing that, and that led to some very exciting things. But it's still kind of under wraps, because it's so pivotal to the experience of the game that I'd rather that players don't know about it. It's like the surprise ending of a movie or something: you don't want to tell people going into the slasher movie who survives at the end or whatever. But that thing was strong enough that it was clear that this is the game I had to make next.

But when you're talking about a spoiler you're talking about a mechanical spoiler rather than a narrative twist?

JB: Yeah. You know, there probably will be narrative twists in the story but they're not the focus of the game, whereas this other stuff is game mechanical. Like things that happen, things that you interact with in certain ways.

How do you strike the balance then? Because while I understand exactly where you're coming from, the challenge is then trying to explain to your potential players why they should play this game when you're not willing to say what it is.

JB: Yeah.

You're kind of relying on your pedigree a little bit.

JB: A little bit is definitely walking a tightrope. For sure, as the game comes closer to completion, we're going to go around to the press and provide copies of the full game and let them play it and...

I don't know if we're just going to ask really nicely that they don't spoil these things. I don't have like... you know, someone like Ubisoft or EA who publishes a lot of games can say, "You know, we're embargoing this information and if you violate it we're gonna blacklist you." or something. I'm not a giant, fascist corporation like that, so I simply...

[chuckles]

JB: Well, that probably will never be the way I do things. And so, you know, I just have to do it a different way and what... I'm still figuring out what that's going to be.

So with Braid, I think what you maybe tried to achieve was creating a few different worlds that worked under different rules to our reality and playing with that. With that in mind, what are you trying to achieve with The Witness?

JB: So the core idea of the game is exploration and puzzle solving, right? And puzzle solving itself is a kind of exploration, it's like a thought exploration; like, "What happens if I were to do this?"

There's a space in your mind that you're moving around and looking at a puzzle from different angles. But then both puzzle solving and exploration have this element of perception, right? Like for a puzzle you want to be aware of all the "What are the relevant things?", "Am I missing something?", "Is there something right in front of my face that I'm not seeing here?", right?

With exploration it's like that but it's kind of tuned in a different way. It's like, "Oh! I see something way out there! That looks really cool!", you know, "I want to go over there and explore that", right? So it's perception driving what I want to go do, so perception is at the core of the game.

And there's this idea of surprise where if you pay attention to something in the right way, whether it's solving a puzzle or something else, you may be surprised by what you find. And so, you know, like "a-ha" moments where in Braid... Braid had puzzles where, you know, they're just really simple, minimalist level design and there's not much going on and it's like, "I don't understand how I could ever get that puzzle piece up there because there's just not much for me to do."

And then people play with it a bit and then they're like, "Oh yeah, I get it now!", and it's something really simple that they just had to do. Those are the most magic kind of puzzles there.

And so taking that kind of thing, that little bit of epiphany and doing it in what I hope is a little bit deeper way, and closer to the everyday world by putting it in 3D -- being a world that's closer to the one we walk through everyday. So that's kind of the core of the game.

On top of that, supporting that kind of feeling and that kind of experience are more traditional game design elements; like, "Hey, here are puzzles that you solve. Here are objects that you can manipulate." and whatever. But those puzzles that you solve and the objects that you manipulate are not the core point, they're just ways of getting there.

From what I've seen of the game so far, it's not very prescribed to the player; you're just exploring and discovering. Even though Braid was couched in the story, it was still very much like that. You were kind of just dumped there, and then tried to feel out the boundaries and rules of the game through trial and error. You seem attracted to that way of doing things. Why is that?

JB: Part of it may be as simple as that's just my personal style. Actually, certainly The Witness is more non-linear than Braid. Braid was structured sort of as a traditional left-to-right platformer with some non-linearity... like, you can choose to walk right by things if you don't want to, and then sometimes the levels would open up and you could pick which ones you want to go to. When you're playing it, you kind of know what the preferred route for things is, right?

In The Witness, it's much more like... I mean, the actual gameplay is nothing like Fallout 3, but it's something like that where there's just this big world. And once you gotten out of the training steps area, you have total freedom to go where you want and to pursue the ideas that you want to pursue. That, for this game, certainly that has something in common with Braid.

And for this game, it has something to do with those themes that I was talking about earlier, about perception, right? If you're going to make a game that's about perception and about surprise, then people have to be free to look at something, or not to look at something, or to go somewhere, or not to go somewhere.

If you're doing a very linear style game, like if I'm doing a first person shooter like through corridors all the way to the end of the game, I don't really have that much choice about what I'm doing. So there can't be this kind of mechanism where I get an idea to do something that isn't obvious and then I do it and it pays off in a way that wouldn't have been obvious.

Because with those games, the player has to know what they're doing at all times or they're stuck. So it just allows for a different kind of mental space to happen. I don't feel like that was a very good explanation, but... it's what I got for you right now.

Okay, so looking at Fallout 3 as an example, you do step out of the vault and then you've got freedom, but at the same time you've got a core storyline. You can visit all these offshoots, but you still kind of know what you've got to do. How are you going to communicate that kind of that main path through your game? NPCs?

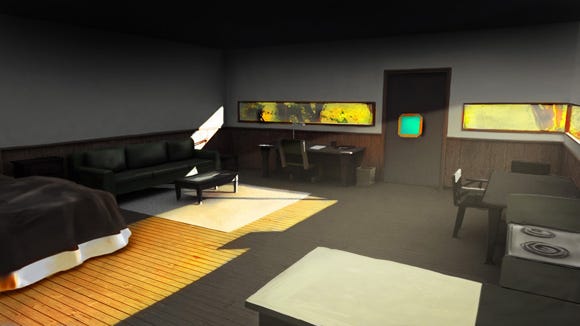

JB: There's nobody that you talk to in this game. There is right now a story, and I use that word very loosely, which you find audio recordings, like you might in a game like BioShock or something like that. So there are characters involved in this scenario that you're in, but you don't meet them.

And aside from production values and requiring a lot more money to do characters well, interacting with live characters is really not what this game is. It's about the opposite of that, it's about being in a kind of an alone, isolated space. So I wanted this feeling that people had been there, but they're gone now. And who were they, and why are they gone, and why are you here, and are you going to leave, right? That feeling of loneliness in a beautiful space.

So there is a kind of like through line of a story-ish theme, but it's very non-linear. You might find elements of it in a different order than another player might, and so you put them together in your mind possibly in a way that's influenced by the order which you found them, and that might make it different from what somebody else puts together.

It's interesting you say that. It seems like a theme in Braid as well. It's just you, you're on your own, and even though there are enemies in Braid you still, that sense of there was something here before and then gone.

And I noticed this with Adam Saltsman's games as well. Do you think that's got anything to do with the way in which you work? For both you and him -- solitary programmers as your background, and not working with big teams.

Do you think that reflects something about you?

JB: It might. Yeah, I mean it seems undeniable that like... if you're in video games and you're able to do substantial projects, you probably spent a lot of your life figuring out how to do it, because video games are hard to make, right? So that's got to be formative on my personality or on somebody else's personality.

It's hard to say for sure because I haven't spent a lot of time working on big teams. I know that I don't like it, mainly for reasons of you're always having to compromise, you can't just get things done, and there's all this inertia; it becomes a political process, and I don't like political processes. So I would say that there probably is some degree of influence there.

Part of it, though, is also that... I feel like parts of what I'm trying to do is explore territories that are underrepresented in games. And so, you know, Braid had a certain kind of sadness to it, while at the same time having upbeat and hopeful elements; it was a mixture of things. And you know, if you think sadness in video games, it doesn't often get done except in a very direct like, "Oh you killed my son!" or whatever. And so I found that ambiguous kind of sadness to be what I wanted to do there.

And The Witness actually is less sad and more hopeful. It's a little bit of an emotional sequel to Braid in that way, even though the gameplay has nothing to do with it. You know, even though you're alone, in this game it becomes alone with a purpose, with a good reason for being alone that becomes revealed as you understand more about what's going on.

And as for the next game... the game that I am thinking maybe the next game... is very abstract, so it's hard to even call anything in it a character, so I don't know how I would file that. But maybe it does.

So you've been talking again recently about things that you perceive as damaging game design trends, which is kind of in a theme that you're known for. My perception of your work is that you value games that level the player over games that level the avatar. Do you think that's true, and would you prefer it if all games functioned like that?

JB: Well, you know, it's really difficult to say. I don't want to be in the business of saying that all games should be anything. Because I think that, actually, there should be a variety of all kinds of games. That's what makes things healthy, right? Like all the time, the way we progress in anything -- in science, in arts, or whatever -- is that totally out of some left field corner, some surprising thing happens and it moves us; it causes a paradigm shift. So having a wide variety of games, I think, is the most healthy thing. I don't ever want to say, "Don't make that".

However, that's not the situation that we have right now, right? What we have is, there are a large number of a small set of kinds of game, and there's all this territory that's kind of unexplored around it.

And so when I go and give lectures like that, I feel like it's a good idea to call attention to certain unexplored things and say like, "Hey, maybe this is valuable". And then also on the other side, like what I was doing in my most recent talk [is to] say, "You know, a vast majority of our games that we're making -- and almost all of them -- have these certain design trends in them and I actually want to question that trend because I do think it's unhealthy."

Now me personally, as a designer, I think very much about when I make something and I'm going to put it out into the world... You know, Braid sold hundreds of thousands of copies, right? That's hundreds of thousands of people playing a five-hour, four-hour... however long it is for them. And that game has an impact on somebody's mind, like that's just how it is.

And so when I do that and I'm putting something out with that kind of volume, I have to care about what it's doing. It's doing something to the minds of my players, and the question is, "What is that?". And for a lot of games, you know, going back to really old games like Pac-Man or something, what the game does to the mind of the player is mostly about just teaching them the basics of the game.

Like, okay, I'm this yellow guy and I'm eating these dots and these ghosts will kill me but I can eat the power pill and chase them. You don't know that before you ever sit down to play Pac-Man, but at first you know it and then you learn how to strategize around that or whatever, right?

So there's a learning process that happens, and that can be a very positive thing. And I think to a large extent, that's what games are actually about, is learning. So then the question is if games are about learning, if every game teaches people something, then if I make any particular game, what is that game teaching people?

And obviously there's always this very game mechanical level of things that it's teaching, but usually there are subtler things as well. And so what I try to do is think about what those subtler things are, and make sure that I feel okay about that. And call attention sometimes when I feel like there are huge trends of subtle things that are very negative that are being done to a large volume of people. I just feel like I ought to say something about that, because very few game designers think about things that way.

So getting back to the first part of the question, while doing all these talks, I don't ever want to say to any specific game designer, "You shouldn't make some kind of game." Actually, that's not true. I would say that about most actual games -- like, you know, even back when I gave a talk a couple years ago saying like, "Hey, I don't think World of Warcraft is that great".

I still wouldn't tell people, "Don't make that game" exactly, I would say, "Think about what you're making and be careful when you make it and try not to exploit players." But I mean now that we've got FarmVille and stuff like that, I pretty much would say "don't make that kind of game" because I don't see much value in it.

It's only about exploiting the players and yes, people report having fun with that kind of game. You know, certain kinds of hardcore game players don't find much interest in FarmVille, but a certain large segment of the population does. But then when you look at the design process in that game, it's not about designing a fun game. It's not about designing something that's going to be interesting or a positive experience in any way -- it's actually about designing something that's a negative experience.

It's about "How do we make something that looks cute and that projects positivity" -- but it actually makes people worry about it when they're away from the computer and drains attention from their everyday life and brings them back into the game. Which previous genres of game never did. And it's about, "How do we get players to exploit their friends in a mechanical way in order to progress?" And in that or exploiting their friends, they kind of turn them in to us and then we can monetize their relationships. And that's all those games are, basically.

And there's this kind of new way where people are, like Bryan Reynolds working on FrontierVille and stuff, making it supposedly deeper, but that kind of thing has been very token so far. And in fact, I would argue that the audience of that kind of game doesn't necessarily want a deeper game, or certainly that's not proven; it's very speculative.

So I would say don't make that stuff. If you want to make a Facebook game, there are a lot of very creative things that could be done, but the FarmVille template is not the right one.

A long-winded answer to your question.

Don't you think that there's a sense where FarmVille has sort of perfected some of those systems that a lot of mainstream games are going for? Like even say, Modern Warfare 2 or something -- the multiplayer aspect of that where you are constantly being pulled back in by these rewards and peer esteem?

JB: Yeah, and I think that that's a negative trend in games, actually. I gave a talk a few weeks ago about that. There's a lot of psychological research that actually shows that this kind of thing, if we use it a lot in game design and we are, that in long term may de-motivate people and make people feel like games are less fun.

There's a book by Alfie Kohn about this called Punished By Rewards, and he talks about this idea of reward scheduling. Basically, setting up any kind of situation where you tell somebody, "If you do a certain thing that I want you to do, then I'll give you this as a prize".

And that happens a lot in Western society, right? Whether it's grades in school, or bonuses in the workplace, or whatever. Certainly in American society, and probably in British society as well, there's just a fundamental belief that this is how you -- in a lot of ways -- this is how you get people to do better work or be motivated; you give them bonuses for performing well.

But actually, research shows that that kind of reward system only works for very boring tasks; it makes boring tasks more variable and more interesting.

But if there are interesting tasks, what it actually does is convince people that they're not interesting. There's a lot of reasons for it, but one of them that's kind of intuitive is like -- especially if you're a kid in school or something -- "Oh, they have to bribe me in order to do this. That means it must not be worth doing on its own." Right?

So there's this idea of intrinsic motivators versus extrinsic motivators. Intrinsic is when you really want to do something, extrinsic is "I'm getting paid to do it, whatever the payment is, if it's achievements or level ups or whatever." The more you get paid in this kind of string-you-along way to do something, is found in general by decades of very consistent psychological research, the less motivated people tend to be for interesting tasks.

That could have two effects. One could be people enjoy games less and end up only doing them for these rewards, which is kind of what's happening in game design, actually. And the other thing that could happen is that... because games are made through this cycle of focus testing and refining things and when these rewards become a major part of the game, that's a big part of the focus test and so now people are looking at, "How do we make the rewards work the best?"

And if they work the best in situations where the gameplay is dull, then you gravitate towards games where the gameplay is dull and it's all about the rewards, right? Because that's the system that works the best when you're reward heavy. So that may be happening as well.

And I don't want to give the impression that I'm putting out a doomsday scenario and like that this is for certain going to happen, but there are a lot of reasons to believe that we should be very careful when we're going about designing these kind of systems, and we're not being very careful right now. We're just pumping them out as fast as we can and that is not necessarily a good thing.

But also, at the most recent talk that I gave was more from a design ethics standpoint. You know, game design used to be about "Hey, I like video games and I think they're cool and I have this experience that I think would be cool to make it and I'm gonna give it to my players because I want them to have a good time.", right?

And it's becoming less about that and more about this explicit manipulation where, you know, I've got a carrot attached to a stick and I'm just pulling you along. And I don't feel that that respects players, and I don't feel that it treats them as human beings, really.

You know, again I wouldn't go tell designers stop using this kind of reward structure because it's useful sometimes. And part of this talk I gave last month was that it's actually very hard to design a game without any kind of reward structure; it's always there to some degree.

But what I would like designers to do more broadly is think more carefully about what they're doing, and just understand the consequences. And if they choose that kind of reward structure, great. But what I find is right now it's not being thought about enough, and that's what bothers me.

How do you feel about putting your game out on Xbox Live Arcade, where you're forced by the requirements to add achievements? How do you approach achievement design when it's a forced part of certification of your game?

JB: Yeah, I don't like that at all. For Braid, I would've much rather not had achievements. What I ended up doing was just putting in achievements for the default things that you might end up doing. Like, getting through chapters and then completing all the puzzles in a chapter and finishing the game and then doing the speedrun.

But yeah, unfortunately it's a requirement of the platform. I have a problem with that not just for all the reasons that I've explained, but also from more of a pure game design standpoint. The kind of game design that I'm finding myself doing is very much about subtlety and focus. It's about like, "Here's a very specific kind of experience that I want players to have".

And there's a lot of communication, especially in The Witness -- a lot of it is about communicating subtle things to the player. And having, as a designer, kind of intent about what I want the player's intention to be, or what they should be aware of at any time is a very important tool.

And suddenly when you start dropping achievements in the game, it's like, "Oh yeah, you could be doing this main game, but you could be killing 300 orcs in a row or you could be doing this or that". And it all of a sudden defocuses player intention.

Which could be totally great for some kinds of games. Like if you want to make a kind of game that's a grab bag of "Here's an open world and there's all kinds of crazy stuff and you pick what you're gonna do and you go do it and it's exciting." That is a kind of game structure that could be very successful and has been very successful for some people.

And, you know, players really like that. Like some players play through a first person shooter and they like it and then they want to go do the, they like find all the things; it gives them more replayability, right? That is all true, and for many games that kind of system can add to the experience. But when you require it, then suddenly you dilute the effect of these other games; you make it actually almost impossible to make these very focused games. And I don't like that. I wish that they were optional.

Well I guess when you're trying to make a game that's all about exploration and trying to work out what you're supposed do, there's a danger that players just look for the achievements straight away as a kind of "This is your list of things that you need to do", and it kind of takes away all of that effect.

JB: Yeah, and we haven't decided platforms for The Witness. When we do that, if it's a console that requires achievements, probably my approach would be to make them all secret achievements. And then try to put them in the game in some way that they don't disrupt gameplay and that they come at interval times. I don't know exactly what that's going to be, but I'm figuring it out.

But here's another problem, is that The Witness, part of the game design from the very beginning, there's no text in the game.

There's verbal communication that you can hear, there's like these audio logs like in BioShock and stuff, but the first time you hear one you're also warned that listening to these things is not a good idea necessarily. You might want to do it but you might not.

There's a tension set up at the beginning of the game, that you might want to ignore all this linguistic stuff and play all this nonverbal communication, or you might want to. But there's absolutely no written text anywhere in the game of any kind, and there are reasons for that in the plot.

And suddenly I have to pop up these boxes that say "Achievement Unlocked:, you know, ba-ding ba-dang! or whatever. I can't make a game without text in it now; I'm not allowed to. Like, what the hell is wrong with... I don't know, it just it really bothers me.

Or you can use Wingdings or something like that.

JB: [chuckles] Well, they'll fail you for certification for doing that. So I don't know.

It's a challenge.

JB: Yeah. I mean, it's even a challenge even beyond the achievement thing, right? Most people who play Xbox 360 games, have the little friend note flyer popped up, even though they maybe don't use it very often. And so you're trying to play a game and you get interrupted all the time by like "so and so started watching a movie". And that's fine, but it's like if I'm trying to make a game that's very subtle and very quiet and stuff, even if people aren't necessarily using that because it's defaulted to on, it's going to kind of like mess with that game experience. So I don't know.

There's a very low attention span tendency to the way things are being integrated in the games these days. I mean, you know, it's the classic thing of old people are just like "kids these days have no attention span!" That's terrible, right?

I don't find anything wrong with short attention span games; like WarioWare is a really fun game. But if the future environment becomes so full of pop up things that I can't make that subtle kind of game anymore, because it doesn't work, because there's just too many things grabbing people's attention, that would make me kind of sad. I don't know, we'll see.

And then finally, I'm just interested in maybe what you're playing at the moment and enjoying.

JB: Super Crate Box, is the most recent thing that I've been playing. Again, they do a lot in that game with a small number of elements, and that's really exciting. It's obviously a very low production value game.

Super Meat Boy, another "Super Blah Blah" game. Really interesting platformer that's well designed in many ways. It's sort of following... there's been a trend in indie games for a little while about games with low punishment levels, you know, where you die and you can try again right away and stuff.

It's interesting like that could've been done in the 1980s, back when all these platformers... but we were still in that mindset of "You've gotta kill the player to make them play through all these levels from the beginning" and whatever, right?

To make money, I guess.

JB: Yeah well, that's how it started. But then once you have a home like for Nintendo console or something, you don't need to take their money. So why was it, it was just that we already established that tradition. You know, some other games do that like VVVVVV does that and whatever. But Super Meat Boy does it so much more in that... it gets so hard, like ridiculously difficult, but it works.

Again, it's like a leveling up the player kind of game where you could... you think some level is totally impossible and you play it for like an hour and you finally get through it, but then you play the game five or six more hours and now you can go back to that impossible level and you can just breeze through it really easily.

And that's fascinating, it's like obviously this game has made a change in the player that's effective somehow. And it might be only limited to Super Meat Boy, like the only skill that I'm learning is within the scope of this game, but it's still very interesting to me.

So I finished the game in the light world way, and I played a bunch of the dark world but I've not completed it, in as far as I've gotten I definitely feel like I've gone on this epic journey of difficulty and I've come out as a different person on the other end. And that's a weird feeling to get from something that's like, it's just a platformer where you just try not to hit obstacles.

And that's part of the magic of video games that I feel like almost has been lost in modern game design. Because in the old days, every game design that was, there weren't that many games. Every time someone made a game it was wacky and new, right? And now we've got all these traditions, we've got like first person shooters and whatever.

Once in a while games do things that are kind of magical. Like Modern Warfare 1 did a couple of things that were pretty different, like getting shot in the beginning and, the nuke thing, and all that. Those were kind of magic moments, but they were very narrative magic moments. Which I feel like is easier to do because we have this example of film and all that.

But like Super Meat Boy has managed to do like, and it's not the only game, but it's managed to do some kind of interactive magic moment where it takes a long time, it takes a lot of dedication, but it pays it off. And that's really fascinating, and I'd like to see more of that.

But it's hard to do when our idea of a game is, you know, "Let's make something just like that last shooter but... set in the 1950s!" I'm not naming names here. But the fact that it's being done means that that's cool and we're still progressing and new design ideas are coming in.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like