Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Game designer Tynan Sylvester takes a close look at how games, alongside most forms of entertainment, "meticulously trigger human instincts" to create emotions and desires, suggesting ways these compulsions can be used positively.

Game designer David Sirlin once wrote that World of Warcraft keeps people playing by tapping into their latent OCD tendencies.

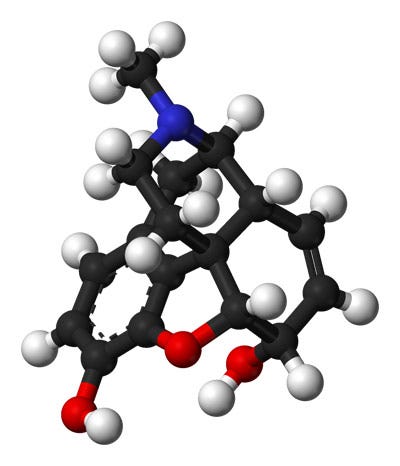

OCD is short for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, a psychiatric condition characterized by recurring anxieties which can only be resolved by performing meaningless rituals. Some OCD patients have to put their shoes on several times in the morning. Others walk a certain number of paces around their bedrooms before sleep. WoW players search for new gear.

At first, I agreed with Sirlin -- that's how WoW made so much money! Those devious Blizzard guys were preying on people's compulsions. The game just baits people along with a condensed stream of awards and an artificial, easy-to-climb social ladder. Damn those evil Blizzard devs!

Then I started thinking about just why people play other games, and I realized I was being hypocritical, because all game-playing is compulsive on some level. To understand this, we need to look at the concept of motivation itself, starting right at the bottom: just why does anyone do anything?

Contrary to popular belief, humans do not act in pursuit of physical sensations. The taste of great food, or the physical sensation of orgasm, are not our primary motivations. These things do matter, but they do not drive major changes in our behavior. What is really important to us is satisfying compulsive urges and maintaining good emotional states.

The only thing all of our ancestors have in common, right back to the first primordial replicator particle in a puddle on a hell-like early Earth, is that they reproduced successfully. Most of those ancestors were too stupid to think abstractly through a problem and weigh possible outcomes.

The solution that evolved was to simply react in certain genetically preprogrammed ways to certain predefined stimuli. Most creatures have rules like, "If you see a predator, move away fast" or, "If you see food, smell it. If it smells right and you aren't full, eat it." These rules are still in us today, and manifest themselves as compulsions, urges and cravings.

Not all compulsions are about direct physical results. Wolf pups, for example, play-fight with each other regularly. Play-fighting produces no immediate benefit for the wolf pups. It does not feed them or heal them or keep them warm. They do it because wolf pups who compulsively play-fought learned to fight and hunt better than those that did not, and thus reproduced more, passing more of their genes onto the next generation. The play fighting compulsion is a genetically selected trait because it provides an advantage by making the wolf learn combat and hunting skills.

Similarly, humans are also endowed with a whole smorgasbord of compulsions, most of which are only indirectly related to survival or reproduction. These compulsions and emotional triggers are what drive virtually all of our observed behaviors and habits. They are also the reason why human behavior is so irrational.

For example, I bite my nails. I don't do this because I think it makes them look good, or because I enjoy the taste. Ragged nails certainly aren't getting me any girls, or making me richer or healthier. There is no rational reason for me to do this. Even so, I and millions like me compulsively bite our nails simply because it is in our nature to do so. This is mildly obsessive-compulsive behavior, probably the expression of a genetically-coded compulsion towards self-grooming and removal of foreign objects from the body.

Compulsions manifest in different ways. As with nail biting, many of them appear as small momentary urges. There are others, however, which work on a much longer timescale. These compulsions control us by dosing our brains with pleasurable or painful emotions in response to various stimuli.

Emotions can be just as painful as a punch in the gut, or as pleasurable as the best meal on Earth. Emotional pleasure and pain are so powerful that we structure our entire lives around finding ways to fulfill our emotional cravings. The performer likes being onstage because he likes the feeling of having people pay attention and react to him. The rock climber likes climbing because of the rush of danger and triumph she gets from conquering a difficult cliff. The S&M submissive likes being whipped because it makes him feel secure under the control of a stronger personality. In all cases, these people's entire lives are built around satisfying their characteristic emotional needs.

We are all addicted to the happy-chemicals our glands brain release when stimulated, and we will do anything to get a fix. Just as with a heroin addict, this includes taking insane, life-threatening risks, directly self-harming ourselves, or inflicting vicious cruelty on others.

Endorphins are naturally produced feel-good chemicals in the blood. The word comes from 'Endogenous Morphine', which means 'Morphine produced naturally in the body'. It's the same stuff.

Now imagine we could invent a machine which would artificially trigger those incredibly powerful compulsions? If it was really well-designed, we could get people to sit in front of it for hours every day. A crazy idea!

Not really. They're called video games. Gaming is an industry which makes money by building machines to meticulously triggering human instincts in ways that they were never intended to be triggered.

We are not unique in this. Most forms of entertainment can be interpreted as "emotions in a box". You buy the product, and when you use it, you get the desired emotional state. The unique thing about game design is that we work behind a double layer of indirection. We do not influence people through direct interaction as with a salesman, or indirectly through a predefined set of stimuli as with a novelist. Instead, we create systems, which in turn create stimuli, which then make players want to play the game. Our advantage is that if we do a good job, the game system can put out far more stimuli than we put into it.

If we're going to use a machine to trigger a person's compulsions and emotions, we need to know what those compulsions are, and what triggers those emotions.

Differences in genetics, age, sex, and conditioning mean we each have a unique set of compulsions and emotional needs and rewards. The most consistent compulsions are the genetically programmed ones. These are also the easiest to analyze so I'm going to focus on them here.

Since our genes are direct results of the process of evolution, we can categorize our compulsions and emotional triggers by how they would have helped our ancestors reproduce. This is not a perfect system of categorization. Human behavior being as complex as is, these drives can never be clearly or unambiguously delineated, and their interactions can be wickedly complex.

I will only discuss a small subset of inherent compulsions, which are themselves a small subset of all human compulsions. This is just the tip of the iceberg.

The Compulsion to Learn

It's 80,000BCE. On the plains of prehistoric Africa, a very average tribe of early humans lives. They do all the normal cavepeople things. They hunt animals, make music, and have little cavepeople children. Nothing unusual about them at all. In this tribe are two cavemen, Thag and Blag. Thag and Blag have equal intelligence, equal physical strength, and equal looks.

One day, after a successful hunt, the hunters all have a few days off. Thag spends his time off lying around and relaxing. Blag, for some reason, does not. He is struck by an odd desire to repeatedly throw his spear at a wooden target. He does this for a few hours, and goes to sleep. Nobody thinks much of it.

Eventually, the next hunt comes around. Thag and Blag are out on the prowl. A deer jumps. Thag throws his spear and misses. Blag throws his spear and hits, due to the practice he got with the piece of wood. Blag gets credit for the kill, his social status rises, and he eventually manages to mate with more cavewomen than Thag. Thirty years down the line, Blag's children outnumber Thag's, and his compulsive spear-practicing genes outnumber Thag's do-nothing genes.

Repeat this story a few million times, and we are the result. We compulsively seek opportunities to learn essential prehistoric skills. One of the main ways of learning those skills is by playing games, just as Blag enjoyed throwing his spear at a target.

Games teach in ways that study and instruction cannot. Even today, in highly trained professions, game playing can still be an effective teaching tool. Doctors who play videogames have been shown to work faster and make fewer errors when performing laparoscopic surgery (1). Pilots are trained on simulators. Soldiers are trained with mock combat competitions. Playing is learning.

These are some of the ways we play games to learn.

The Compulsion to Learn by Practice-Fighting

When I was a kid I used to be obsessed with weapons, warfare and violence. I read enough books about weapons and warfare that I became a child expert on military history and tactics. I played countless games about war. I ran around with toy guns, designed nonexistent space battlecruisers, created and played war strategy games, and of course countless video games. I spent a large part of my childhood preparing for a war I'll never fight, and a hunt I'll never go on, simply because it is in my genes to compel me to do so.

The compulsion to practice-fight is a very popular one for use in games. All games with warlike or violent themes of any kind will trigger it. It is easy to trigger because war is so physical, overt, visual, and dramatic. There is nothing subtle about the things that trigger this compulsion.

Unfortunately, the fact that it is so easy and obvious means it is very overused.

The Compulsion to Learn by Practice-Nurturing and Socializing

Social and nurturing skills are just as important to us as fighting and hunting. We need to learn how to maintain and gain social status, how to interact with family and friends, and how to care for our young. It is a compulsion which tends to be stronger in females, who are specialized for nurturing roles in prehistoric societies.

A teacher in ruthless methods of social manipulation, which are useful in adult life.

Consider Barbie. The entire Barbie line of toys can be thought of as a training program for teaching girls how to maximize their social status. They learn social roles and interaction through roleplay, they learn fashion and beauty by dressing and making up their Barbie, and they learn to create and decorate a home. Girls compulsively do these things because these behaviors teach reproductively useful skills.

The Tamagochi toys are also is based on this compulsion. Personally I spent more time driving my Tamagochi insane with endless punishment (maybe this compulsion isn't that strong in me personally), but I know people who actually nurtured theirs.

Powerful as this compulsion is, it is not commonly used in games for a variety of reasons. First, game developers are predominately men, and this is a more female compulsion.

Second, directly simulating social interactions is impossible because computers do not have the context knowledge to have a real conversation. Third, social interactions and nurturing involve variables and objects which exist only in the mind, which makes it difficult to conceptualize the mechanics them since they lack a physical presence. Visualizing feelings on a screen is not easy.

It's a shame, because the compulsion is so powerful. Anyone who can effectively trigger this compulsion (Will Wright, please stand up) will make a lot of money. Working with this compulsion is tricky, but I think that there is a lot of unexplored potential here.

The Compulsion to Learn by Hearing and Telling Stories

Remember Blag, the spear-throwing caveman? Now let's look at two of his sons, Clag and Zug. They both like throwing spears at targets, just like their father, so they are both skilled hunters. At night, however, they can't see their targets, so they cannot practice spearthrowing. They must find something else to do.

This is when their behavior differs. Clag sits around and does nothing before going to sleep. Zug, for some reason, feels compelled to go and trade stories with the other hunters.

One day, Clag and Zug are out hunting separately. Clag finds a strange new berry and eats it. Zug finds the same berry, but he recognizes it as the new poisonous type that one of his friends told him about. Clag, not having heard the story about the new poisonous berry, eats the berry and dies. Zug's genes, which made him compulsively seek out stories from his friends, thus outnumber Clag's non-story-hearing genes in the next generation.

I recommend everyone read The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins. It's a great help in understanding evolution, and some of the non-obvious results of the evolutionary process. One of the principles of the book is that the "unit" of evolution is the gene, not the organism. This means that we are programmed to give advantages to our genes, not to ourselves as individuals. The interesting thing about that is that our genes exist outside our body. Our relatives often have exact copies of our genes. This means that genes which encourage us to help our relatives at little cost to ourselves will proliferate.

Since most of our evolution took place in very small societies, we are programmed to treat any friend as likely to have copies of our own genes. One way to greatly help friends and relatives at little cost to you is by telling them stories.

If you've ever seen the movie Apocalypto and managed not to burst out crying, you may remember a scene in the initial "happy tribe" section of the movie where one of the tribe's old men sits and tells a story at a campfire, while the rest of the tribe listens intently. Note how intently the younger people watch him speak. This is realistic. Human beings are genetically compelled to tell and hear stories.

The passive media we compete with -- movies, books, television -- are largely based on the story-telling/story-hearing compulsion. I don't think it is a good idea to try to compete directly with these established media in quality of embedded stories. Forcing an embedded story in a game requires serious design compromises. We can do it and it has been done, but it is not the strength of our medium.

Instead of embedding a story in the game fully formed, games can generate stories which players will then tell each other. Any FPS player will have a few stories about crazy plays he pulled off. I once walked into a room in Counter-Strike and killed three guys who were stacked on top of each other by filling the bottom guy with lead and letting the others fall into his place like Connect Four pieces. That was cool. Another time in Halo, I was firing from the minigun on Warthog and got hit by a rocket. I did an entire midair flip without ever stopping firing or losing my point of aim. That was cool.

These stories don't have to be about combat. The Sims has an entire array of features about taking photos of your Sims and assembling albums chronicling their lives, which can then be posted on the web.

The Compulsion to Learn by Experimenting in a Safe Environment

Experimentation with any kind of low-risk, unknown, dynamically responding system tends to be fun. Little kids are known to poke, prod, smell, and taste nearly everything they come in contact with. In my case this included a hot stove (I learned something useful).

There is a game called Garry's Mod, which basically consists of a toolkit to help you abuse the Source engine physics system. You can spawn characters and items. You can pose characters, or attach items to characters, vehicles, or each other. You can create thrusters and explosives and trigger them by remote control. It's a physics playground, and it is popular because it allows so much experimentation.

The Sims is a good example of this as well. I enjoyed locking my Sims in rooms and seeing how long it took for them to starve to death, or seeing how the game reacted when I did strange things which I would never do in real life.

The strength of games as experimental tools is that there are no consequences in the game. This means we can try out crazy new ideas which we would never do in real life. Realistic flight sims can be used to try out unorthodox fighter tactics, for example.

Another interesting this about experimentation is that it becomes boring as soon as we fully understand a system. In order for a system to be continuously experimentally fun, it needs to continuously display unpredictable but logical responses. The entertainment value of a system will fall off as the player learns to accurately predict its output. There is no reproductive advantage in studying a system you already know.

Similarly, if a system is so random as to be incomprehensible, there is no entertainment value. There is no reproductive advantage to studying a system which is random since it cannot be understood. Like already-learned systems, unlearnable systems will not trigger this compulsion.

This principle is one of the main determinants of replay value. Games which depend on the experimentation compulsion can be replayed as long as the system they present offers logical but somewhat unpredictable results -- as long as the player is continuously learning.

After a person's material needs are satisfied, and they are securely safe from predators and enemies, hunger, heat, and cold, the main remaining avenue to increasing reproductive success is by increasing one's social status. Status allows access to more mates and higher quality mates. Accordingly, human beings are programmed to pursue social status. In a modern post-scarcity society, shifts in social status and social position are the main drivers behind most of our serious emotions.

Once, walking into a socially competitive nightclub, I noticed is how people were huddled together in tight groups. They looked like people in the Montreal winter, trying to escape the windchill. The men huddled at the bar, or along the walls. The people on the dance floor huddled in circles. Nearly nobody was alone, or if they were, they were walking or talking on the phone.

The comparison to huddled masses in a cold wind was not far off, because standing alone in a club is just as painful as standing alone in a freezing wind.

Standing alone causes a perception of friendlessness, leading to a loss of social status. The human unconscious is tuned to recognize status shifts, and to pump you with the appropriate motivating chemicals. In the case of standing conspicuously alone in a club, the subconscious will pump the brain with pain emotions.

Therefore, just as huddling together in winter keeps us from the physical pain of cold, huddling together in the club keeps us from the emotional pain of status loss. If you watch for it, you can almost see the gusts of status blow around the room, following attractive people, and you can watch everyone else shuffle around to stay warm.

This is just one expression of one emotional trigger related to social status. Human beings have countless compulsions and emotional triggers like this. There is an entire class of emotions -- embarrassment, triumph, pride, humiliation -- which are used to describe feelings caused by status shifts. As compulsion engineers, we can compel players to play our games by triggering these emotions properly.

At first glance, it may seem that this class of emotions is only important for multiplayer games. Not so. The environment that your compulsions evolved in never included any computer-simulated people, so your genes lack a system to differentiate between simulated and real human interaction. As a result, these compulsions can be triggered by computer-generated people (although only in certain ways, and the emotions will tend to be less poignant).

These are some of the ways we are compelled to gain social status:

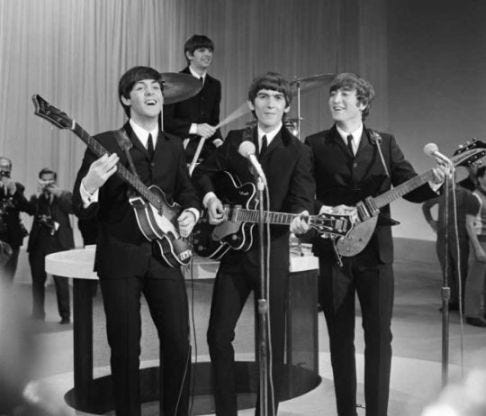

The Compulsion to Gain Social Status by Showing Impressive Skills

Being impressive is a great way to gain social status. Even if you logically know that a high Counter-Strike kill count is never going to get you laid, the drive to be perceived as exceptionally skilled remains. Any game with a skill component triggers this compulsion. It's even more powerful in online competitive games since there are human opponents, who provide an audience and a social ladder to climb.

These guys loved performing. This feeling of enjoyment evolved to make them perform, thus increasing their social status and getting them lots and lots of girls.

This compulsion often overlaps the compulsion to defeat competitors. A group of musicians will naturally compete to be seen as skilled -- especially if there are attractive mates listening.

The Compulsion to Gain Social Status by Defeating Competitors

Remember the scene in Braveheart where Wallace stands on the field of English dead and screams at the sky? Imagine how that felt.

Since people who have a compulsive desire defeat competitors will tend to win more competitions than apathetic people, they will reproduce more. Over time, the compulsion to win has proliferated. The word triumph describes your programmed emotional reward for defeating a competitor. Wallace got a big dose of that when he defeated the English -- and he sure enjoyed it.

Competition doesn't have to mean combat. Contests of ability appear everywhere. An apparently benign conversation often has an undercurrent of social competition just under the surface. School grades, athletic skills, pain thresholds -- nearly anything can become the basis for a competition in the right social context.

This compulsion often overlaps the compulsion to show impressive skills.

The Compulsion to Gain Social Status by Acquiring Cool Stuff

Material wealth and social status are closely connected. As a result, we are compelled to acquire things.

A long time ago, I played the original NES. There were lots of beat-em-up games for this system. There was one game called River City Ransom. The combat in this game was not that great. I became hooked on it not because the combat was interesting, but because it was possible to acquire stuff. I kept coming back to the game so I could feel the emotional rewards of buying new things -- even though those things did not physically exist.

This compulsion shows up in any game with an inventory or array of stuff. The obvious examples are RPGs like Diablo. These games are very carefully tuned to constantly dangle new and better loot in front of the player, never frustrating them with slow progress, but never allowing them to get all the items and finish, either. By keeping the player in a middle ground, they maintain the compulsion to acquire almost indefinitely.

The compulsion can be amplified when other players are involved. Games like World of Warcraft are based on this. Other players provide a social ladder to climb, and associate positive social reactions with the acquisition of new items. This amplifies the compulsion.

The Compulsion to Gain Social Status by Building Impressive Things

Creating something really cool is a good way to get social status.

Consider this essay as an example. I'm enjoying writing this. Writing these words could even be described as compulsive. I don't really think my ramblings are particularly impressive, but the compulsion to do something that I self-identify as being good at is strong in me as anyone else. In this case, the compulsion will hopefully will result in an eventual increase in social status upon publication of this article.

Devious game designers can take advantage of this compulsion and trigger it deliberately. Example games include obvious world-builder games like The Sims or SimCity. Less obvious examples appear in certain ways of playing low-pressure or turn-based strategy games in which players have a chance to build a beautiful base or a cool custom-designed warrior.

This compulsion can commonly overlap with the compulsion to acquire cool stuff.

"...when you buy furniture, you tell yourself: that's it, that's the last sofa I'm gonna need. No matter what else happens, I've got that sofa problem handled." - Edward Norton in Fight Club

When I have a lot of things to do in little time, I feel a palpable sense of anxiety. Similarly, when I clear one of those things off my plate, I feel a sense of relief. These are emotional responses tuned to push us into action when situations threaten to get unmanageably complex.

Games can trigger these same emotions -- both the anxiety related to an unsolved problem and the reward that comes with resolving it.

The Compulsion to Make Progress by Simplifying Problems

I used to play StarCraft. Back when I sucked even more than I do now, I used to like playing maps with lots of resources in one place so I could just sit and build up a beautiful defensive line, which I would foolishly convince myself was unbreakable. Next, I would spend huge amounts of time building some unbeatable army. Only then would I venture out on the attack. Of course, as soon as I came up against an even moderately good player I would get my ass handed to me on a platter.

I was succumbing to the compulsion to simplify. I wanted to solve problems and therefore not have to think about them again. The prospect of constant upkeep and surveillance, as is required for a viable dynamic defense strategy, seemed unpleasant. In my case, this compulsion destroyed my StarCraft game (eventually I realized what was wrong, and started occasionally winning matches against small children).

Triggering this compulsion is generally done by presenting the player with a complex situation which can be simplified. Single-player RTS games are like this. You start with a complex and hard to control situation involving multiple AI bases, and are challenged to take down these bases on by one. With each enemy base destroyed, the game becomes simpler. Eventually you can toy with the last enemy base at your leisure. That final release of pressure is the emotional payoff.

Any game that starts out complex and becomes simpler will trigger this compulsion.

Purely linear entertainment products, like film or books, are self-limiting. They always run out. Games, however, do not suffer from this limitation. This includes pre-computer games like card gambling.

Gambling with cards is well known to be addictive for some people. Gambling addiction has destroyed many lives. There are support groups for those addicted and their families. Similarly, some games are so effective at compelling people to play for extended periods of time that there are support groups dedicated to breaking game addiction.

But wait a minute. Gambling addiction destroys your bank account. Drug addiction destroys your body and brain. But the entire reason we play these games is because we are evolved to compulsively do so, since these compulsions are evolutionarily beneficial. Games are tools for learning and socializing. A person who plays chess or basketball for hours every day is called dedicated, not addicted.

I've personally learned a lot from countless games that I played throughout my childhood. I learned World War II history from Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe. I learned about municipal tax systems from SimCity. I learned about the stock market from Railroad Tycoon II. I learned about Roman history from Caesar III.

Even games with no real-world analogue can teach deeper skills. StarCraft taught me about dynamic defense, when not to plan ahead, and how to manage complex situations under pressure. Counter-Strike and Unreal Tournament taught me hand-eye coordination and teamwork.

But what about a game which teaches nothing useful, and is so good at triggering compulsions that it can force people to play continuously for years? What if it could engineer a compulsion to play so powerful that it destroys the rest of a person's life, and they get nothing back from it? Does this make us the moral equivalent of casino owners? Not evil, but maybe just a little bit suspect?

Maybe. I don't think that creating powerfully compulsive games is unethical. But I think that a game should do more than trigger a person's compulsions.

Games could be incredible tools for elucidating a concepts -- whether those concepts is educational, philosophical, or political. Games can hold attention for a very long period of time. They can and communicate ideas differently from other media because we can actually force the player to live some part of a reality instead of just reading or watching someone else's story. We can put people in anyone's shoes and show them a tiny bit of what it is like to make that person's decisions. We can teach systems through exploration and experimentation instead of just showing results.

Games like this are showing up, but slowly. DEFCON: Everybody Dies (2) is a mechanically fun but thematically horrifying game about trying to "win" a global nuclear war. September 12 (3) is about trying to stop terrorism by killing people -- which, in this game, tends to create more terrorists.

These games show promise, but there is so much more territory to cover. For most of gaming's history, we have been more concerned with figuring out how to generate compulsions to care about whether our games say anything. Maybe now we can all start using our medium for something greater than psychological button-pushing.

1. Phend, Crystal. "Video Games Hone Laparoscopic Surgery Skills". Medpage Today. http://www.medpagetoday.com/Surgery/GeneralSurgery/tb/5089 Accessed December 4, 2007

2. Introversion Software. DEFCON: Everybody Dies. http://www.everybody-dies.com/

3. September 12. http://www.newsgaming.com/games/index12.htm

4. Wikipedia: Images.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like