Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Sam Barlow, writer and director of FMV game Her Story, offers a fantastic breakdown of the video scrubbing mechanic of Her Story follow-up Telling Lies.

Gamasutra Deep Dives are an ongoing series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game, in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren't really that simple at all.

Check out earlier installments, including creating the gorgeous voxel creatures of Fugl, designing the UI for VR strategy game Skyworld, building an adaptive tech tree in Dawn of Man, and achieving seamless branching in Watch Dogs 2’s Invasion of Privacy missions.

I set up the company in 2016 to follow up my breakout indie game Her Story and develop Telling Lies. Prior to that, I had worked in the games industry for a while, most notably on a couple of Silent Hill titles including the narratively adventurous Silent Hill: Shattered Memories.

One of the most notable aspects of Her Story was the mechanic of searching video clips as the central (and only!) exploration element of the game. It was a meshing of narrative and gameplay that hadn’t quite been seen before and because of that - and in large part thanks to Viva Seifert’s central performance - it found and delighted an audience.

In deciding to follow up Her Story, I was interested in really digging into the core idea of exploring video and adding further layers of expression and choice into the central mechanic. Despite being a spiritual successor of sorts, the game also has a very different tone, scale and subject matter to Her Story and I wanted the mechanic to be an important part of expressing that. Out of our early explorations and thought experiments, we deconstructed the idea of scrubbing video, and this became a core feature. We invested a lot of the development effort in this one element, and it became part of the visual signature of the game, highlighted even in our teaser trailer:

This is how the game works, as described in a production document:

When I design, I start with two touchstones - first (1) a feeling I want to communicate to the player, then (2) I try to latch onto a metaphor that captures and creates that feeling. The metaphor is where the game mechanics and the player’s imagination meet - it describes the role or action they will perform. Sometimes the metaphor becomes more or less literal, and stops being a metaphor. With Telling Lies, the feeling was that of holding onto memories of a failed relationship, the mush of sensory and emotional beats wrapped up in hindsight. The metaphor was that of a surveillance job, the kind where the surveiller is so immersed in the private everyday of the target’s life that they feel like they know them intimately.

The game is about surveillance. A big part of the concept is to take the intrusive 21st Century surveillance that happens digitally, invisibly, and make it more tactile. I thought of the types of surveillance baked into popular culture. Old fashioned surveillance, the stakeout, the wire-tap, involves waiting, watching, listening - physical acts (of concentration, endurance) on the part of the spy. With the game I wanted to involve the player emotionally and intellectually in the process - insert them into the ritual.

The surveillance job has its own familiar tropes and pacing. The visual of someone scrubbing through hours of concealed camera footage or CCTV records (“Stop! Back up and enhance!”). The wiretap cop listening in on hours of mundane conversations for the one breakthrough. The mundane punctuated by revelation.

These ideas led me to think on questions of time and presence. The game is about watching pre-recorded video clips - in a gaming context, inert and dead. Movies have the sense of being alive because they proceed in real time - are unstoppable. I wanted a navigation mechanic through the video that would allow plays to ‘traverse’ it but with some friction so the real-time nature of the clips would not be entirely erased.

This meshed with my thoughts on structure. A key part of Telling Lies is the idea of being dropped into a scene in-media-res - you can be dropped into a scene at any point in its duration depending on the word that gets you there. This would communicate the sense of the world happening around you, of being the surveiller who overhears or glimpses something that happens on its own timescale, not put on for your benefit; and from the deductive gameplay perspective, to have additional layers of context to infer. Players are dropped into scenes in the midst, and must ask ‘What is happening right now? Who is this? Where and when is this? How did they get into this state? Who are they talking to?” To support this fundamental thrill, it was important that, having been dropped into a moment, movement away from it was not instant or frictionless.

Player is dropped into the video where the character speaks the word, “men”. If they want to see how the scene got here they can head backwards in the video, or see what happens next, faster or slower.

So, rather than have a timeline that could be hopped about at will, it became clear that instead giving players the ability to scrub through video would address these ideas. Players could not entirely bypass the flow of time in the clips, and had a new way of exploring directly. It would make the video more real and tactile in the way that walking and running through a gameworld makes it real.

It also provides further expression for the player, who is always driving the experience. With this mechanic, the player is able to scrub video like a DJ scrubs a record - slowing down to focus on and exaggerate an expression; rewinding to rewatch a moment, skimming through another sequence to drop back into a heavy narrative beat. This notion of allowing the usually-passive audience of video storytelling to be expressive is fairly unexplored, and further builds on the idea of players driving the storytelling in these games.

Research

When I have a metaphor for my game, I explore other media to see depictions of it, especially if it is a popular trope. This can bring details and further understanding to the game.

A big inspiration was this sequence from The Conversation. The movie focuses on a single recording made by surveillance expert Gene Hackman. The story sees him repeatedly listening and re-listening to the titular conversation and his attempt to discern the truth of it. The way the movie fetishizes the analogue tech and the process of rewinding gave me further reference for how the scrub can be tactile and feel special.

A movie that riffed on The Conversation was Blow Out, with this virtuoso sequence of editing. Similarly the weight of the machinery and the feel was perfect.

Both these examples combine the effort of the surveillance thriller with the insight/revelation as the truth is sought out.

This latter example highlights something else I was reaching for. Working with video performance, I had observed that a film editor’s experience and POV of the footage is so different to that of the audience. Obsessing over single frames, exploring and enjoying the deep dive into the performances and faces, the editor wallows in the sheer joy of taped performance. I’d had a similar experience with the art piece 24 Hour Psycho. In it, Hitchcock’s Psycho is slowed down to last 24 hours - each frame taking 30 seconds. With no soundtrack, you are just drinking in the visuals, the faces, eyes, frames, lighting. This tied into both the idea of the sensory power of memories and the scrutiny of the surveiller.

Another art piece that inspired me was David - Sam Taylor-Johnson’s video installation of David Beckham sleeping. I loved the texture of this piece, its intimacy, the room it created for you to react and think around it. It made me think a lot about what it means to watch (and be in a position to watch) someone sleep. But, outside of the gallery, the pacing and lack of incident would make this texture excruciating to an unwitting audience (see: the floor sweeping in Twin Peaks Season 3). It occurred to me that a player, with the power to scrub through, or jump out of this clip could, however, make the choice to watch. And having made that choice, they could enjoy these kinds of textures as much as I did. In Telling Lies, we get to watch a couple sit in silence when words fail them, a child sleeping, a troubled man washing dishes, a bored cam girl lounging, etc. There is something special and interesting in all these scenes if the player wants to look for it.

So, I started to solidify this idea of allowing players to scrub through videos, embracing the analogue feel of The Conversation, using it to give players expression but also give weight and texture to the clips.

I was reading interviews with the director, Nicolas Roeg, and re-watching his movies, seeing how he used non-linearity to evoke the feel of human memory - of how we remember relationships. One detail stuck out: Roeg was fascinated by the subjective effect of rewinding film - from the moment he first saw an editor wind footage backwards on a Moviola machine. There’s a further marriage of the feeling and the metaphor here - a further way to deconstruct the narrative and play with the arrow of time. Our memories do not come to us in chronological, linear order. And likewise, in being dropped into a clip, by scrubbing backwards or forwards, the player is as likely to uncover new information. To encourage this, we set up our scrubbing so that players can read the subtitles as they scrub, so playing backwards or forwards they can still follow the gist of the conversations. Watching a scene backwards is a valid way to play.

The Moviola in all its glory.

As I focused on these ideas, I saw many parallels with (inarguably!) the greatest game of this century - Zelda: Breath of the Wild. The feel of that game is like nothing else, and in trying to create something similarly refreshing, I clung to the ways the game resonated.

The generosity and meaningful freedom in Zelda: Breath of the Wild

In that game, Nintendo promised freedom and allowed players to move in any direction. There is a scale to the world and the friction of movement - the effort to scale cliffs, to cross huge fields - adds weight to it. It allows players to soak up the atmosphere and the heft of the world. There is traversal and re-traversal, there is pausing to take in the view and there is galloping across a plain, or gliding down from a mountain. BotW has fast travel, but it is limited to shrines, forcing players to walk and ride and stay connected to the world.

I committed to treating our scrubbing like the traversal in Zelda - I can scrub backwards or forwards, fast and slow, but always there is inertia or friction - a connection to the video itself. I felt the synergy with this idea and the work of the spy/cop/agent. There is reward in climbing a mountain in BotW, and there is reward for the diligent surveiller who discovers an event. In both cases, the player makes the thing happen; they discover it. The scale of the effort lends something to the discovery. And there is little obfuscation. In BotW there are few UI elements or map markers or detective-vision overlays; there is a stripped down purity to the world and your being in it. In Telling Lies, I wanted to retain the purity - video, lots of it, and the player.

And I was excited with Telling Lies that the other aspect of the game - the ‘search mechanic’ which allowed you to teleport across the two years of narrative with the correct word - would be boosted by the scrub. Adding the connection to the sense of time within the clips would make the magic of teleporting outside them much greater.

Lastly, something I wanted to tackle within this mechanic was to push against the FOMO players might feel. I had been surprised by how many players 100%'d Her Story, and wanted to find ways to free them from that obligation here. In giving the players long clips full of sleeping-David-Beckham textures, I did not want them to feel compelled to sit and watch the entire clip - to lawn-mower all the content. The choice to do so was there (similarly, I can climb every mountain I see in Zelda if I wish). I wanted them to skip across and around and lose themselves in the jumble. So, giving them a traversal mechanic for the video that required effort would at least push against that desire. To more clearly elucidate and weight the choices available to the player, I wanted to make the ‘rewind to the beginning’ option less engaging. If you do it, you are climbing a mountain.

Having absorbed the influences and the rationale behind this mechanic, we set out to implement it in the game.

With BotW’s traversal in our mind, we knew that this core mechanic had to be fun in-and-of itself (the Nintendo figure-of-eight test - it is fun in a Nintendo game just to run a character around in circles). This meant it had to be responsive, expressive and aesthetically pleasing. We pushed the video player to allow us to scrub video frames as close to 30 or 60 frames per second where possible, depending on the platform. This required a lot of fine-tuning of the video players on different setups!

I was obsessed with the clunky moment found when reversing direction on an old VCR - the moment of zero G where the tape winders re-engage - and compared it with the joy of seeing a character skid their feet to do a 180 turn in a game; or the handbrake turn in a driving game. Rather than actually make the game as unresponsive as an old tape machine, we settled for having the reversal happen swiftly, but have the inertia occur in the audio. With the audio itself, we auditioned many different sounds and layers of sounds, many of them more ‘digital’ in keeping with the tech of the game. But I kept coming back to the more analogue sounds that evoked tape technology. Just as guns in sci-fi movies often still make noises like our guns, there was something about how these sounded that communicated our desired behavior.

When scrubbing we also played with the video audio - should it be heard, speeding up and slowing down? Forwards and backwards? What we found was that this often distracted from the drama, or became too surreal. Instead, we dropped video audio and mixed up the game’s music (if it was playing), mixed up slightly the sounds of the ‘in game’ apartment, and focused on the scrub sounds themselves - highlighting that in this moment we were more ‘in the world of the scrubber’ than the world of the videos. It also had the benefit of focusing attention on the visuals of the footage, on the faces and expressions skimming by, the spoken words flashing up as subtitles. There was an early idea for Telling Lies where the characters would never be seen speaking, focusing entirely on their expressions - and in the scrub, fast or slow, we returned to this idea.

In defining the controls themselves, we came back to the importance of the mechanic being fun and expressive. We threw out existing paradigms for video fast forward and rewind and created our own. To make it expressive and fun, we thought of the ideas of a conductor with their baton, or a DJ running their fingers over a record. The player should have control over the speed of the scrub and with mouse pointer or touch screen, move their finger/hand across the screen to control the videos. A direct, responsive connection, and one that allowed for the odd unconscious flourish. We iterated the mapping of speed to arrive at a non-linear ramp that gives players the ability to noodle around at lower speeds/slow motion. There is also that idea from the surveillance job, of work or effort - the player does not just hit ‘rewind’ and sit back, scrubbing is always direct and active. You have to push the video all the way to where you want it.

Testing

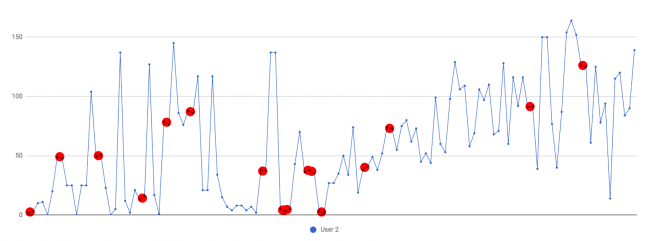

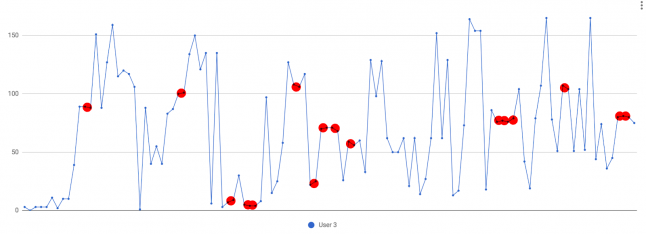

When testing the mechanic, we recorded play sessions and data which showed us how much time players spent scrubbing vs. watching; how many clips they watched; how often they jumped in and out of clips. We tweaked the scrub speeds between sessions and stopped when we arrived at the fastest speed which still discouraged players from excessive rewinding. We also determined which maximum speeds would still allow (and encourage) them to read scenes as they scrubbed via the subtitles.

Graphs tracking users’ sessions with the game during tests - used to track how they navigated the database

We shipped the game!

One aspect which surprised me (as much as the 100%ers of Her Story) were the players who attempted to rewind every video to the start and so found the scrub mechanic an impediment. As I discussed above, the scrub mechanic was partly designed to frustrate and discourage exactly this behavior - what I hadn’t allowed for was (a) the expectation that the game would play out like Her Story and (b) people’s heightened familiarity with everyday video players (Youtube, Netflix, etc.) meant they were not prepared to deconstruct or re-invent the act of watching video. This is always going to be a risk if you design a feature to negatively steer a player (they keep on anyway!), but I’ve always been attracted to designs which do this. I’m not sure how to have avoided this because we’re getting to the heart of the design. Perhaps the solution would be to more overtly explain the possible play styles. An older, less-free Nintendo may have had Navi appear and say, “Hey! Stop rewinding so much. You don’t need to!”

But overall, the focus on this mechanic of scrubbing in Telling Lies delivered everything we wanted. It was highlighted in reviews along with the unique texture of the videos and, anecdotally, I have heard from players about how well it created the feeling we wanted. In testing the game, I would often find myself dwelling on a moment, scrubbing slowly through the frames and expressions as music swelled around me. In one final playtest, a player remarked that it reminded him of working on old Moviola machine - I hope Nicolas Roeg would have been proud.

You May Also Like