Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Flinthook’s fluid, accessible hookshot is the result of months of design work, solving problems from controller mapping and aim-assist to the role it takes in the game.

It might be called a grapple, or it might be called a hookshot. It might be bouncily elastic or responsively taut. It might launch you into a lazy swing or fling you towards the grapple point.

There are many ways to express the concept of throwing out a line from a player character that attaches to a surface, something that’s familiar to many first- and third person 3D games, from Ocarina of Time to Spider-Man 2.

But the hookshot is curiously underused in 2D platformers. Tribute Games’ new action-platformer, Flinthook, might give some pointers as to why. Not because Flinthook isn’t good. Quite the opposite, in fact.

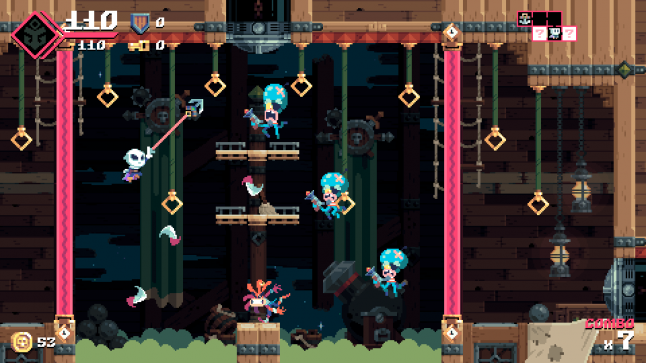

This Rogue-like about boarding procedurally generated spaceships and stealing their booty is built around the concept of hookshotting around its arena-like rooms.

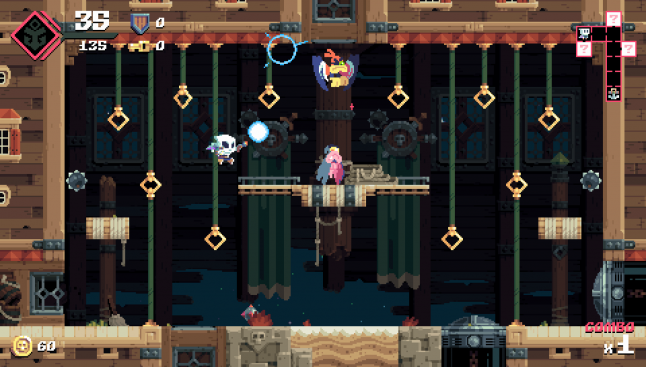

It seamlessly augments the standard platformer moveset of running and jumping; fluid and accessible, it’s also powerful, able to launch the player at speed across the room. But Flinthook’s hookshot is the result of months of design work, solving problems from controller mapping and aim-assist to the role it takes in the game.

Tribute’s focus, after all, was for players to be able to focus entirely on the moment-to-moment action, dodging bullets and defeating enemies, not carefully aiming the hookshot. And the first challenge was designing the game’s controls, which took Tribute on something of a journey.

The Montreal-based studio had previously made Mercenary Kings, Wizorb, Ninja Senki DX and Curses ’N Chaos, all games with a decidedly console sensibility. So they naturally designed Flinthook first for controller. “The first prototypes we tested were a no-brainer,” says programmer and co-designer Jean-Francois Major. “Twin-stick, so you move around with the left stick and aim with the right.”

But they immediately ran into issues. Prime among them was that the design ruled out the use of the face buttons, because players’ thumbs had to be kept on the right stick.

The thing with Flinthook is that your little buccaneer has many different tools and abilities. You’re armed with a gun and the hookshot, and you can slow time as well as use consumable items.

You can interact with objects, whether to buy items, pick them up or talk to NPCs, and, of course, you can jump. Flinthook needs a lot of buttons.

“So we were limiting ourselves to the bumper and triggers, and they’re tricky,” says Major. “Not a lot of people are able to use both a bumper and trigger at once; people tend to swap from one to the other with their finger and it felt awkward.”

Moreover, he found that playtesters would tend to aim and move with the sticks in the same direction, rather than use them independently. “So that’s when we decided to try to put both on the left stick, which would free up the face buttons and make the triggers available.”

This is how Flinthook controls today, so you shoot and hookshot toward the direction you’re headed. While on paper it might sound limiting, even frustrating, that you can’t move and aim independently, in practice it feels natural. In fact, it helps reinforce the sense that this is a game about constant movement.

But Major wasn’t completely comfortable, worried that players used to twin-stick games would bring expectations to Flinthook. “We knew we needed to explain to people coming from The Binding of Isaac that it doesn’t play that way,” he says. The issue was compounded when, towards the end of production, they started to think about mouse and keyboard controls.

They found themselves inescapably drawn towards using the mouse to aim, separating aim from movement again. They tried free aiming with the mouse cursor (but it relied too heavily on the player having to keep track of where it was) and locking the cursor to the player (it felt better but still required the player to look at it too much), and eventually settled on a final scheme in which you aim by simply swiping in that direction.

“But by going that way we’re telling people it’s possible to have twin-sticks in our game, and now some people are asking why they can’t have it on the controller,” says Major.

“People have expectations, and it’s hard to convince them that yeah, this is how you play this game. We see on forums people saying, ‘Oh, you should design your controls like this,’ but they don’t take into account that we already tried those things. There’s probably a way to squeeze it on a twin-stick controller but we’d have to sacrifice some things. With our button mapping we’re not sacrificing anything.”

Part of Flinthook’s fluidity is down to its animation, in which the rope loops out towards a ring and then put pulls the character to it as it latches on. And a lot is down to its auto-aim. “It’s not really that crazy,” says Major of how it works, but it looks in a 30-degree arc from the point the player is aiming at and then works out what hook-able elements are closest, which is most meaningful, and directly latches your hookshot onto it. Clean and reliable, it allows you to simply trust in it as you focus on the action.

In play it feels as if there are many things you can hook on to, but in fact there are only two types: rings scattered in every room, and enemies encased in a bubbles, which you need to pop by hooking before you can defeat them.

This functional restraint smoothes out the logic behind what the game auto-aims at. In the case of a ring and a bubbled enemy being nearby, it’s most likely that’ll be the player’s priority. “Because if there’s a ring you don’t want them to hook onto it because it’ll pull them towards the enemy,” says Major.

That simplicity, once again, was down to exploring lots of different avenues for what the hookshot would be used. At one point it could collect coins and other drops (a feature that Tribute found slowed down the platforming). At another point it was a weapon that allowed the player to hookshot an enemy, grapple towards it and then melee attack it. It also took the form of a projectile that would deal damage without grappling the player towards the target.

As they explored each, one idea that Tribute liked was having the hookshot take a leading part in a combo system in which you could chain together actions while in mid-air: you’d hookshot an enemy, staying frozen in position while you shot another, or took an extra jump, or grappled a ring to move somewhere new.

“But what we found out was that it was better to have two separate abilities,” says Major. And so in the released game, the player’s weapon is a rapid-firing gun, and you can hookshot at the same time. The hookshot itself is almost instantaneous, extending fully in two frames. “That was really important in getting a good feel; it had to be really fast and decisive. Initially it was more physics-based and it didn’t feel as satisfying.”

And while that separation meant gutting the combo system, in its place is something more organic and momentum-based. Early on, players would stop moving once they reached the ring, but Tribute realized it felt good when their retained their impulse, and that they could add a splash of extra nuance by allowing them to cancel the hookshot mid-flight, keeping the impulse they’d collected so far.

That momentum supports the sense when playing Flinthook that you can – and should – be flying all the time. Its hookshot’s success lies in the way it feels so simple to use, folding smoothly into play.

But it’s the result of hundreds of decisions, from small ones to huge, made across months and months of development. The hookshot is a familiar concept, but as Tribute found, there’s lots of design potential in it.

You May Also Like