Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The long-awaited Mercenaries 2 is a key title for EA-acquired developer Pandemic - and Gamasutra talks in-depth to creative director Cameron Brown on the game's creation and influences, from Will Wright to Jerry Bruckheimer.

Mercenaries 2 is Pandemic Studios' first next generation project - and also the company's first game to ship since the Destroy All Humans! and Star Wars: Battlefront creator was acquired by Electronic Arts as part of the BioWare/Pandemic acquisition.

In this in-depth Gamasutra interview, Creative Director Cameron Brown lays out a roadmap for the game's development, speaking of how the studio's relationships with EA, its previous owner Elevation Partners, and sister studio BioWare affected development.

He also discusses the travails of developing a next-generation open-world game, and the original inspirations for the series, which was initially published by LucasArts, but for which Pandemic retained the IP - and has now brought to EA.

The game has been in development for, I would say, an extremely long time. Could you first talk about when you initially had planned to ship the game, and...

CB: Yeah, I guess a little bit -- I mean you're kind of talking to the wrong guy. I'm the creative director on the project... so frankly, it's probably my fault if we have been in development for a long time; it's probably because of all the crazy stuff I want to do.

But yeah, I honestly don't remember what the original date we released for the game was. But yeah, we didn't get it finished in time; we wanted to just make sure that the thing was a polished and as cool as we could make it. We felt that, you know, adding in the co-op stuff that we're doing -- obviously, this is Pandemic's first next-gen game, and there was a lot of work... not a lot which we anticipated.

It's just that these are huge games, open world games, and I think if you look at some of the comparable games -- like you're going to see GTA IV come out soon. The number of people, and the amount of time taken to develop these games is just -- it's not literally an order of magnitude beyond last-gen, but it's a significantly more complicated endeavor.

And again, it just takes a lot of time. I can't point to any one thing, you know. I can't point to co-op or to any specific feature in the game that really pushed us out. It's just that we got to where we could move into bug testing, we could get through submission, we could ship this thing... But it's not going to be what we originally envisaged, so we elected to take more time.

You know, it's been an interesting time for Pandemic. As I'm sure you know, during the development of the project, we went through two phases of the company. First of all, working with Elevation Partners and John Riccitiello, as an Elevation studio, which gave us a lot of financial freedom to make those kinds of decisions.

If we were under a more traditional game deal we may have no option but to ship at this point, but under Elevation we were able to go, "Oh, well, we are independently funded, we're able to hold up and keep developing." And I remember this whole big discussion between us and the Mass Effect guys, about who was going to make it first. Obviously they did.

And then once Pandemic was acquired by EA, that was another change, but it also brings a lot of economic backing, and a lot of resource backing to us. That means we really can develop a game of this magnitude. This is not a -- like I said -- this is not an endeavor to be undertaken lightly. It's been a huge and fascinating ride for all of us... the sheer complexity of these games, and particularly a game like Mercs, where you've got -- where we allow the player so much freedom.

You know, we've got all the destructible stuff, we've got just hundreds of vehicles, we've got weapons, we let players approach objectives from literally any angle -- and they could be coming in on foot with a shotgun, or they could be coming in with a tank or a helicopter. There are 18 different kinds of air strikes.

You know, this adds a huge burden to the engineering effort, to the design effort. And then you add in co-op as well, so you're adding another variable to that mix. It's just a huge game! It takes a long time! (laughs)

You talked about going through changes at Pandemic. First of all, did this game actually start before you were acquired by Elevation Partners?

CB: Um, yeah, only just. Like, we shipped Mercs early '05, obviously, and the team did a bunch of other stuff -- I personally went and worked on Destroy All Humans a little bit, some of the other guys we know worked on Battlefront II -- we made a couple of internal demos, and looked around at some different IPs before settling on Mercs 2.

And at the start of Mercs 2 we actually had primarily an engine development team for almost a year, we were just working on tech and tools, and really upgrading our pipelines to next-gen.

So the game itself, we didn't really get seriously into until probably the beginning of '06 -- and at that time, we really focused on the PS3. Spent a long time making sure that we were squared away with the PS3. And yeah, it started before the Elevation acquisition.

It's interesting to see people's reaction to EA, and the changes that had been happening at EA. What's your take on that, and how has it affected your project?

CB: Well, I have to say there has not been much... I've really said, there has been no direct impact on the day-to-day development. At least not so far. I think there's been some significant changes to -- we've had to integrate parts of it, the active side of the business, and obviously there is a huge, and very interesting, frankly, resource pool.

We're starting to talk to some of the other teams, and kind of start to share some of the techniques. It's really interesting to be interacting with the Burnout team, or the Godfather 2 team, or just reach out to some of those teams who do work that we're really big fans of -- kind of see what they're doing, and just compare notes. So that's pretty fun.

But, really, so far, in day-to-day development? I think we haven't really noticed a difference. It was kind of the same under Elevation. And that was really the goal -- we felt like we've figured out a pretty good way to, in our own kind of scratch way, to make fun and cool games. And I don't think anyone's got an agenda to really mess with that. So, so far so good.

I know, of course, everyone who works in the industry has an opinion on EA, and their reputation, but our experience has been great. For us, it's kind of interesting, because John Riccitiello was, obviously, deeply involved in Elevation, and was really, really a big advocate of that model. So, when he moved back to EA, he took back a lot of the stuff that he'd been thinking about with Elevation.

And to my eye -- and I'm not proclaiming to be a biz dev expert or anything like that -- it seems to me that he's really applying some of those principles that were behind Elevation. And so far, the kind of "games label" model, and working under Frank Gibeau, from my perspective, has been a delight. Frank's a really smart, really, really sharp guy. So far it's just been a really positive relationship and a help.

And I think for Mercs 3, and for other projects moving into the future, I personally am very excited at doing a much more thorough survey of the technologies, and tools, and information, and resources -- you know, like the usability stuff -- there's a lot of stuff that a big company like EA has that a smaller company like Pandemic just doesn't.

So, one thing you just touched on, briefly, was that you said you spent about a year working on engine and tools and stuff, as you transitioned off of the original Mercenaries.

CB: Yeah, exactly.

Do you have a full home-grown suite? You have your own engine that you're using for this game, and...

CB: Yeah, that's right. We have the Mercs engine for next-gen. We have written it pretty much from scratch, to make this game on next-gen. And we've got a completely upgraded tool chain that was designed to handle the just hair raising number of gigabytes of data that we throw around every day. Frankly, terabytes of data that we throw around at this point.

So yeah, we've got a full home-grown technology suite that runs the game, and has really developed into a really flexible game engine. And that's another part of the interesting stuff for next year: once we ship this game -- which is in the very near future -- it's going to be really interesting to look at this engine and say, "OK, what can we do with this tech? Now that we've invested this time and effort into building it, what's next?"

The nature of Mercs -- I'm not sure how familiar you are with Mercs 1, and the gameplay style of it, but -- it's a very open-ended, very flexible game, that gives the player a lot of options. You've got your flying around, you're blowing stuff up... So, the engine's got a lot of capabilities, so I'm really interested to see where we can take it next.

Are you using it on other projects at Pandemic right now? Or is it specifically Mercs right now?

CB: It's specifically Mercs. The way we work at Pandemic is, we don't do tech sharing in the traditional sense of keeping everyone on the same engine and try and pool the tech.

What we do is, we definitely share tech, but in the sense of branching off, so we have an unannounced title in development that kind of took a drop of our code at an earlier state, and then they've moved forward with it. There has been a little bit of sharing back and forth when it makes sense, but it's not like we have a central tech group and everyone uses that engine, or anything like that. Typically we tailor the technology to the game pretty specifically.

So you think that presents an advantage? Developing technology that supports a specific, let's say game type, rather than...

CB: Yeah, yeah, exactly. Well, you know, the capabilities that a game needs. I think so; that's been my experience. I'm cautious about saying "that's the only way to do it" -- I certainly wouldn't make that claim -- but in my experience, that's been a better way to do it. I think there's a lot of inefficiency around trying to keep that sharing going.

And I think, at the end of the day, what you're trying to do is move pixels in response to what the player wants to do, and I think it's easy to get distracted and really consumed by the principles of technology, and a more theoretical or abstract idea of what you're trying to do.

Whereas, at the end of the day, we're really trying to stay focused on, "It's about the game." There's no point having an engine if you don't have a game that people want to play, and want to buy, and want to enjoy on top of it.

When you branch off with the engine -- when other teams might take and branch -- it's difficult, potentially, to merge back in, if they have tech that they develop, that you might want to use.

CB: Oh yeah, sure. It can be. Yeah, but in my experience -- and again, I want to be really explicit with the caveat that I don't pretend that my experience is necessarily the be-all and end-all -- but in my experience, it's easy to overstate the difficulty of kind of reuniting the technology.

You know, programmers are very smart, and they can usually figure it out, and particularly if the code has the same DNA -- even if, let's say they took a drop nine months or a year ago, fundamentally a lot of the architectural decisions are going to be similar. Things might have changed off of that, but as a general rule, I think it's not too difficult.

Sometimes you've got to be willing to invest weeks or months into reintegrating, but that's still better than starting from scratch and taking years, or potentially spending millions to license the tech, or whatever your other options are.

Now I'm assuming it's full, multi-platform tech. This game is shipping on 360 and PS3 -- is it shipping on PC as well?

CB: Yep, there's PC as well. Then there's a PS2 version as well, which is developed out of house, and using the Mercs 1 tech.

So is the PS2 version actually basically a different game?

CB: Yeah. It has a lot of similarities, but it's really tailored to the capabilities of the PS2, much more. So, you know, it's the same basic storyline, it has the same sort of characters and setting -- it's set in Venezuela -- it has the same kind of core story.

The missions themselves, it's not like there's a one-to-one correspondence between the missions or the world layout, or anything like that. So it's similar, but it's actually its own game, to the point that, as director of the next-gen project, I'm very enthusiastic about when we ship this game. One of the things that I'm going to do on my vacation is play the PS2 version, so I can play a Mercs game that I didn't get involved in every detail of!

That's kinda cool. When it comes to generational transitions -- I guess the game I think of the most is, when the Xbox 360 was still relatively new, they shipped two different Splinter Cell games that year, and they were different games. It's kind of an interesting thing, when that sort of thing happens.

CB: Right. That's been a kind of fun part of going from Mercs 1 to Mercs 2, we're starting to see a lot more expressions of the game universe. There's a comic book now, there's a mobile game that is really awesome -- it's actually, I'm not a huge player of games on my cell phone, but the Mercs cell phone game is unbelievably cool!

It's like this really, really awesome, 8-bit kind of "Commando" Mercs, with like little 8-bit Mattias running around. It's really neat; it's really, really fun, just as someone involved in the creative direction of Mercs, to see other people starting to run with it, and seeing reflections of it in other places. That's a really fun thing.

Let's go way back and talk about -- this series started a few years ago; can you talk about where it came from originally?

CB: Yeah. Well, it's, the original idea of doing a mercenaries game, or a game with a mercenary as the central character, really came from Andrew Goldman, who is our CEO. And his title is CEO, but he really functions as kind-of -- I don't know what you'd call it, but he's the chief creative consultant of the company. He's got his fingers in pretty much everything that Pandemic's made, it has a little piece of Andrew's brain in it.

So he and I were talking, and we're really, we'd really gotten to think about, I guess what we would call... obviously we were heavily inspired by GTAIII at the time. We were just blown away by what Rockstar had done in, really, creating a new genre, and really opening up the structure of the game. We were really inspired by that, and we started talking to each other, and seeing that, wow, taking this into a more military environment -- so, you know, putting it in a war zone, and having the tanks, and helicopters, and focusing more on more epic destruction -- would really be a more interesting spin on that genre of game.

We started throwing around this "GTA in a war zone" kind of idea, and I remember Andrew just came to me one day, and he said, "What if you're a mercenary?" And we started talking about it, and it became clear that there was this really interesting freedom that came from that concept. You know, the freedom to work with whomever you wanted, the freedom to not follow orders, and it really felt like a way to not get sucked into being just another military game.

It really let us have the best of both worlds, in terms of taking stuff from a civilian world -- you know, a mercenary can drive sports cars, and can be in crazy drug lord villas, and do a lot of the really cool civilian stuff that you would associate with an action movie -- but then the merc is just as at-home on an open battlefield, with the tanks, and the helicopters, and the air strikes, and soldiers, and massive battles. So it was really exciting when we started thinking in those terms, and going, you know, you could basically turn up for the battle in your Lamborghini, or whatever, and we're going, "Wow, that's a really interesting idea." And there weren't a lot of games at the time, and there still aren't that many games, using that kind of premise.

Not really, I don't think.

And I remember at the time, I guess it was back in -- I don't remember when it was. But I guess it was in 2002, or something like that. Or 2003. And I remember, it was really like, for me, I was vaguely aware of the private military companies, and the Blackwaters, and the executive operations -- or the executive outcomes, I should say -- it's clear where the executive operations inspiration from Mercs 1 came from.

And I remember when I began to research that stuff, and read into it more and more, and learn about these very corporate, private armies, and these private soldiers. It's just a fascinating world. And once we'd gotten into that -- once we started looking into it, and started thinking about the gameplay possibilities, it just kind of snowballed from there. It became a no-brainer, you know?

The basic concepts for the game, from a gameplay standpoint came first, then you sort of fleshed it out with some basic setting ideas, then you moved forward with finding the narrative that fit that. Would you say that's a fair assessment of how you proceeded?

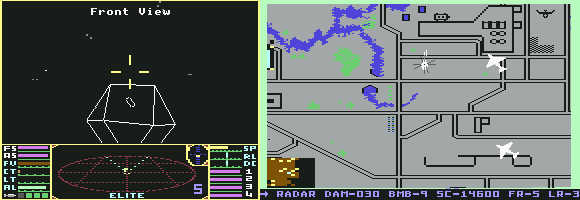

CB: Yeah, pretty much. You know, we definitely started from "let's make you a mercenary". And let's let you work with different factions, and let's really focus -- and from a gameplay perspective, my thing had always been, you know, I really wanted to make something partly inspired by GTA, but also equally inspired by, you know, I grew up -- I'm Australian; I don't know if you can tell from my accent -- I grew up in Australia, and in Australia, the Commodore 64, and the Commodore platforms, like in Europe, the Commodore platforms were very dominant.

So I grew up with a lot of really classic Commodore 64 games as a kid -- you know, Elite, and a lot of the Andrew Braybrook games, like Paradroid -- and they all have this kind of sandbox element to them, where they have these fairly rigidly defined game rules, and then they set you loose in the world.

Particularly Elite, which was agame I was pretty obsessed with as a kid. It's got its rules, you've got the training, you've got your spaceship -- but then you're just set loose in the universe, and you can really, you've got goals, but... you're not told, minute to minute, here's what you have to do. And those were the games I was always really attracted to.

Actually, another really formative game for me was a game called Raid on Bungeling Bay, which I was really amazed to learn many, many, many years later, I learned that that was a Will Wright game, and it was actually the engine he wrote that he used to make SimCity.

So it was... this helicopter combat game called Raid on Bungeling Bay, that, as a kid, I played on the Commodore 64, and adored. It kind of had that element too -- you had free movement over the map, you could attack various objectives at any time. It was very goal-driven, rather than a scripted kind of...

You know, I have a lot of respect for all genres of games -- I have been a game developer long enough to know that there is creativity, and passion, and skill applied to pretty much any genre -- but as my personal tastes go more to the very emergent games... So, you know, I was bringing in to it... there was a great convergence between the idea of being a mercenary, and the kind of narrative freedom, and just the freedom inherent in that role, and the kind of gameplay freedom that, really, as a game designer, I find personally exciting.

And, actually... a lot of the designers that have been on the team for a long time, I think, share that enthusiasm for that kind of sandbox-style gameplay. And, honestly, to this day, I still think that's really something unique that Mercs really brings to the table, is our commitment to that player freedom. We really take it to a level that I think a lot of teams kind of get a lot of the way there, but you know...

I have a saying that I use a lot with the team, that I think is completely applicable to game development: "There's the first 90%, then there's the second 90%." I think a lot of teams go the first 90% -- all the games, I feel that they're the first 90% -- but then they'll kind of back off, and they won't let you go the rest of the way. I think there's a real emergent complexity that comes out if you really stick to your guns and say, "No. These rules are going to hold true without exception, across the entire game world, and the player can just do this any time."

I think it would've been very tempting, and it was very tempting at times, given the technical difficulties, to take something like the airstrikes, and make them into more cinematic, scripted moments. So, like, you had to stand on a specific hill, and you could call in the airstrike on a specific city, and we could craft it. It would have been much easier to make that a crafted, scripted moment. And it would've looked great -- it would've looked great in trailers, it would've looked good in TV ads.

But when you're playing the game, and you've been playing for three hours, and you've got your own personal narrative of how you got to that point, you don't want to be told where to use the airstrike. You want to use it when you want to use it. And I find it's a bit of an immersion breaker when I have to stand on a special flashing spot and press a button and it just happens for me. That's just me, as a gamer, but I certainly don't intend to be judgmental about how anyone else does it.

Well I think it just comes down to the matter that certain people like certain things. It's just like anything else -- movies, music.

CB: Yeah, exactly. So, see, I guess that was all an answer to your question of "how did we arrive at Mercs". For me, it was very -- once I got into that convergence of the idea of being a mercenary, and the narrative freedom, and that gameplay freedom, I was pretty hooked.

And so how do you handle story in the game, given that you're talking about wanting to not take away control, not wanting to deliver scripted things? I heard a lot about this coming out of GDC -- I get a lot of people talking to me about articles about, "Where is narrative going in gaming, and how can we shape it in a way that's compelling -- and not intrusive, but actually rewarding?"

CB: Right. You know what, I know... I'm really interested in seeing what the FarCry 2 guys are doing with that kind of stuff; definitely watching with interest. Our ambitions with Mercs, we tried to recognize what the core of the game is -- I think why people are attracted to the game, I don't think it's necessarily for an emergent narrative experience.

So the solution for Mercs 2 has been to keep it relatively simple, but give you a really compelling, easy-to-follow story. I'm kind-of a real dumbass when it comes to games. I'm a pretty good focus test for my own games, I think, because I emulate people who get confused by game stories -- which I think is most of us, to be honest.

So we've kept it relatively simple. You start out, and you meet the key bad guy in the game. You actually start out, in Mercs 2, working for this guy, and through a sequence of events that play out during the first act of the game, he becomes persona non grata -- he does something to you that really, really annoys you. Moving into the worst insult that you can level at a mercenary -- which is not paying you.

And so, the game is set up with a very simple kind-of overarching premise of, "Go and get this guy." And then we have -- obviously, you've got these factions that you're working with, and we've got a lot of really interesting factions that we've brought into this kind of fictionalized Venezuela. And so, by working with the factions, you're kind-of building up your resources, and uncovering clues, and bringing yourself closer and closer to this final showdown with this guy Solano who stiffed you in the beginning of the game.

Yeah, so, I'm not sure I can give you a crisp answer on exactly how we've done it, but it's really -- you know, we've kind of blended this merc's journey of going after this guy, with kind of half-accidentally, but half through just not carrying very much, kind of igniting this entire war in Venezuela, which, if you really take a step back and look at the story, turns out to be pretty much your fault. Not that you care, as a mercenary.

And so, there's all these -- the world becomes the resources that you can use to build yourself up and go after this guy. You have to play the game and tell me how we did in crossing the street.

A couple things that you said really interested me, but one of them is about delivery of narrative. How do you deliver narrative in your game? Is it through cutscenes, or, like, mission updates, or voice overs during gameplay?

CB: All of the above. There are some cutscenes in the game; we use a couple at the start of the game, really just to set, just to introduce the characters in a way that you'll understand. Introduce the world, and make sure that you follow what's going on. And then you go meet the various heads of the factions, and they'll give you contracts that you're going to do. So, those are presented to you as kind-of non-interactive sequences.

We don't do a lot of them, and honestly, I would say, the primary narrative vehicle for the game is the contracts that you do. So you take contracts from various clients in the game, and that varies from, you'll have very military objectives, like you're going to go level entire cities for the Chinese Army, or you've got to, sometimes it's more low-level but lucrative stuff like you're transporting, like, endangered parrots to these Caribbean pirates, or harvested human organs for these Caribbean pirates... So whatever it is you're doing, that is really the context of what you're doing, and why you're doing it, and who you're doing it for; it fills out the world and advances the story.

There are certain missions that are self-generated -- things that you do, not for a client, but you actually elect to do yourself, in part of your quest to get this guy Solano who screwed you. And those really advance the primary arc of the story. So, you know, you're getting key pieces of information, and key resources that you need in order to move forward.

And so a lot of that happens in the missions -- there are various things that you've got to acquire in order to track this guy down and then attack his [base] where he is. So that happens, actually, in the missions. So to answer your question directly, I would say I think the primary narrative device is the contracts themselves -- the gameplay that you do.

How did you find the right balance? This is a question very much from a development perspective; when people are working on games, particularly more sandbox, emergent games -- you have to deliver some sort of compelling story, for the most part, to support a complex scenario like being a mercenary in Venezuela. It's a complex, abstract scenario. So how did you find your balance, and your techniques during the course of development?

CB: A little bit, there was some learning from Mercs 1. That was something that I felt was definitely not a strength of Mercs 1; I felt like it was a fun game, and it had some really cool gameplay in it, and certainly a lot of people seemed to like it, but I don't think anyone would accuse us of having a really strong story in that game. It was fairly disconnected from the action, and I think a lot of people... well, I've had this feedback directly, but I also believe a lot of people would've gotten confused, and not been entirely sure what they were doing. They would just kind of go, "Well, this is fun, and they're telling me to do it, so I'm doing it."

In Mercs 2, we've invested a little bit more in act one, so we've actually applied a more traditional narrative structure. We front-loaded, in act one, a bit more of face time with the bad guy, a bit more face time with the other characters; we've taken a little bit more care and attention in the flow of the first missions, to introduce you into the world a little more carefully.

The game, for the first thirty or forty minutes, is -- I wouldn't call it a linear experience, but we don't really open out the sandbox to you, probably until thirty or forty minutes in, after we've carefully introduced you. These are airstrikes. This is how you do this. These are the controls. Here are the key characters. Here are your partners that you've got to work with. Here's your base. Here's where you are in the world.

So, hopefully -- and we've been doing a lot of focus testing as we get very, very close to submission, to make sure that everything's panning out as we planned. Hopefully we've done a better job of introducing you to your capabilities, and to the setting.

And I'll tell you, another thing that we do is, we really try and work with familiar-feeling tropes. We're very explicit about being an action movie game; we want to put you into a kind of Bruckheimer experience. That kind of summer blockbuster high action, but it's you doing the stunts, and it's you experiencing these huge explosions. I think, by trying to leverage a little bit of that familiarity -- obviously, we don't want it to feel cliché, or tired -- we try and make it feel like these are fairly iconic characters that you can understand just by looking at them. You're kind of going to get a sense of who these people are, and what they're doing. So that, I think, helps as well.

So it's really a combination of all those things, and then just a lot of iteration -- particularly over the start of the game -- trying to get it so that everyone gets it, everyone's engaged, everyone feels like they're having fun within five minutes picking up the controls, and that kind of thing.

I only touched the first game very briefly -- I didn't really play it --

CB: Right. This interview's over!

(laughs) What I heard people saying is that, you know, "Oh my god! I can't believe that I blew this up! Or that I could just do this, and jump on this!" You know what I mean? It was very much a gameplay-driven game. There's a certain degree to which you have to make sure not to spend too much time on narrative. I think a lot of games make that mistake.

CB: Yeah, exactly. And I'm not going to name names, but yeah, that's definitely a sin that gets committed often, and I don't think we're going to do that. We invest a couple minutes in act one into introducing you to who you are, but I don't think anyone is going to feel like they're stuck watching a movie when they want to be playing a game. We get you into the action pretty quick, that's a pretty strong focus for our game.

But, you know, I think my sense is that people who played and enjoyed Mercs 1, I think they understand what the game's about, and I think they'll trust us that we're going to deliver on what we are promising. And then we are trying to extend a little bit more of a hand -- like you said earlier, when we were talking, that people have different tastes. Some people play games for the story, some people want to go through and experience the narrative and what happens one moment to the next.

Some people -- and I personally am in this camp -- I'm more driven by the mechanics, and the raw gameplay. And to put it in an extreme level, I could almost play some of my favorite games, you could swap out the characters with, like, just boxes, and as long as the mechanics were as good, I'd be almost as happy.

So we're trying to extend a little bit more of a hand to the folks who are really more character- and narrative-driven, and we have a lot of people on the team who are really, really obsessed and passionate about that side of things, so I've let them really step up and, really, make a huge contribution in enriching the setting, and the fantasy, and the character.

And I think, just if you look at the revision of the characters -- we have some returning characters, we have some new characters -- I think if you look at the iterations we're doing on the returning characters, they're just head and shoulders above the first game, and just much richer and more compelling than they were before. They've got much more interesting back stories, and much more interesting looks, and much more interesting attitudes to them.

Fingers crossed!

Good luck with that. I mean, it's a difficult balance, I'm sure, to try this. That's the thing, right -- you can't be everything to everyone. I mean, this is just totally me, my personal opinion, but I find that there's a certain bizarre expectation that everybody will like certain games. Like, there are "good games," and "bad games," and everyone will play the good ones. The expectations are changing -- I think the Wii is throwing that into sharp contrast, because people are realizing -- but there was a certain point where it was like, you know, "everyone should like Halo," or whatever.

CB: Right, right, right, right. Well, it's, you know, people have different tastes, and I think, honestly, a lot of the most popular games -- just to tick some recent examples, if you look at a game like Call of Duty 4, which is a phenomenal game, and one of its strengths is that it knows what it wants to do, and it does it really, really well. And it doesn't try and do everything, you know? It focuses on being just this über first person shooter on the console.

Just as a developer, I know what they must have done to keep the game running at 60 frames a second. That's a huge -- you know, that would've taken a lot of really smart compromises, and a lot of resisting temptation to just go, "Let's do one more effect! Let's do one more shader! Let's do one more whatever!" Yeah, it took a lot of discipline, I'm sure, for those guys to hit 60, and keep it there, but that's what a focus on your core will do. And that's what a commitment to knowing what you're trying to do, knowing that some people just aren't going to get into it, but by really nailing the core of what you're doing.

I mean, for Mercs, we're always very clear on what our core is. I think people who are coming to Mercs, most of them are coming to have an awesome experience blowing shit up; they want to have an amazing amount of free-form destruction, and just incredible catharsis, and that visceral feeling of power. And we're going to deliver that to them, so I think that throughout the nearly three years of development that I've spent on the game, that's been the consistent daily, hourly focus -- has been, "Let's just make this an unbelievable experience!" When you get the controller in your hand, and you feel the power of this game, this is something that no other game is going to give you.

I guess it's an abstract question, but how do you focus on that? Because like you say, the core focus of Mercenaries is, "Let's make this the Bruckheimer movie of games!" You can sit down and just blow shit up, and it's got to be fantastic to do that. How do you stay on course with that? How do you measure that as you're developing it?

CB: Well, I think that one is relatively simple. I mean, I think early on, there's -- I've heard that a lot of different people have a lot of different names for it. I've heard it called "high concept", I know that EA call it an "X". It's like, what is that single idea that really defines the effort that you're doing? And I'm not saying it has to be one thing -- and Mercs certainly has other central concepts apart from destruction -- but for us, it just really is a daily focus.

And because we settled on that day one, in the first kick-off meetings, where we were getting the team together and saying, "Alright, this is what we're gonna do. We're gonna go to Venezuela; we're gonna have these characters; here's the basic story, we're going to flesh this all out", but from day one, we're talking about how we're going to deliver an amazing destruction experience.

Here's an example, right: from Mercs 1, part of the DNA of the team -- and it's not even a question, it never comes up, no one ever comes and asks me as the director, "Hey, Cam, does this thing have to be destructible?" It's not a question. Everything is destructible. It's just part of the DNA of day-to-day development.

And so, the questions I'll get are, how does this thing destroy? How many pieces should it break into? Should it fall over in this way, or that way? Do we want it to crush things when it falls? Can the player shoot it, and it falls down and crushes other things? So those are the discussions that we have -- it's not, it's never, "Is this thing destructible?" It's only, "How does it destroy? Does it need to destroy any cooler than that?" You know what I mean? It becomes part of the DNA from day one, and I think that's the way to do it, at least in my experience.

It's identifying what you think is the core concept, and then messaging it out, making everyone on the team -- I guess there's a certain amount of getting them to buy into it, and embrace it, and understand it. You know?

CB: Yeah, and I think both of those are equally important. I think you can't just pick an arbitrary high concept, or an arbitrary -- when we talk about it, we usually call them "pillars". Or at least that's what I call them, I'll say, this is a pillar of our game! If you take out this pillar, the roof's gonna fall in. There are a lot of features that come and go during development, things that you try, things that work out, things that don't work out -- but you don't want to remove the pillars, or the structure's going to collapse.

So yeah, so I think it's, you have to have a messages that's credible for the team; I think the team has to buy in, like you said. They have to be ableto think about it. Game developers are incredibly smart people -- it's really hard to put anything over on a game developer! So you've got to expect critical thinking in an office, so you can't just say, "Get out there!" and say anything. It's got to be a credible message.

So with Mercs, I think people understand that when we say, "Look, all other things being equal? We're going to destroy everything in the game. It's going to come apart, look amazing, and this is really one of the pillars of the experience." I think people hear that, and I think it's easy to understand, and I think they believe it. And as a result, through thick and thin, and through ups and down, and through the various challenges of development, we've never wavered from that goal. And I think that ultimately, when the game ships, that's part of the core of the product.

Looping back around, you guys merged with BioWare a few years ago, and I know I've talked to people from both studios, about tech sharing, and you talked also about taking a look at things at EA -- how is tech and idea sharing? How does that work for you, over the past couple years, and moving forward?

CB: Well, unfortunately, after the Elevation experience, obviously BioWare and Pandemic are now mortal enemies, and are sworn to destroy each other in an epic battle.

But, look, I spent some time up in BioWare, I went and visited those guys, and because of the games we were making at the time -- when it was just BioWare and us, as real sister studios -- there wasn't much explicit engine sharing or tech sharing that we could do. But something that we did do is, we went up -- I flew up to Edmondton, and got extremely cold, and had a special time looking at their projects, and pitching Mercs to them, and hearing their feedback on an early version of Mercs. Then they came down to us, and presented a couple of their concepts to us, and we definitely used each other -- not extensively, but usefully and, I must say, a pretty fun way -- used each other as sounding boards.

They were definitely interested in our experience in making action games, and they were particularly interested in how we approach vehicles in Mercs; they were like, "We think you guys do really good vehicles! We really want to apply that to..." it's a still unannounced project, so I won't talk about it...

And then, for us, obviously they make some of the best story games out there, so we're really interested to learn from them about, you know, how do you guys approach -- it was fascinating to go and talk to them about their incubation process that they have for writers up there. They take their writing incredibly seriously, and they have such a rich culture up there of video game writing, as opposed to any other form of writing. It's really interesting, and they are developing, and are at the forefront of a really interactive form of fiction. We mentioned, we touched on interactive fiction before, and I think BioWare are clearly innovators and pioneers in that field.

So it was more a really interesting and stimulating discussion that we were able to have, and comparing notes about -- it was the first time in my experience, like video game developers, because of various reasons, we tend to be -- when we meet, we often have to play our cards close to our chests, because we're technically under NDA, and we have unannounced projects, there are questions of competitive advantage in cool things we might be doing... So when we were like a sister studio with BioWare, that was the first time, as a developer, in a long time of doing this, that I was able to march into another developer, and just be very forthright, and be very, "Here's what we're doing! Here's what works, here's what doesn't work! Here's what we think is really cool! Here's our secret sauce!" And they were able to do the same for us.

So, you know, I can't really point to a specific thing -- it wasn't like we took some of the space ships from Mass Effect and put them in one of our games, or anything like that. Much as I would've liked to!

(laughter) That would be a cool, kind of like Smash Bros...

CB: It was nice just, you know, talking to those guys, hearing how they approach problems. And it was really... I'm still processing some of the conversations I had up there, and I still find interesting aspects of what they were doing, and how they were doing it. They're smart guys. I really, really have a lot of respect for those guys.

I think it's perspective, right? Perspective is, you can't judge things that you're working so closely on, the same way someone with an outside perspective can, and that's awfully valuable. I mean, that's basically why they hire focus groups. To add perspective.

CB: Right. Right. No, no, it's true, I mean I don't think that's unique to video games, I think that's common to human endeavors in general. I think the longer you do something, the harder it is to get some distance.

It's the cliché of the painter who needs to take a step back from the canvas, and take a look from viewing distance, and go, "What am I creating, here?" I'm a terrible painter myself, but I'm quite interested in the art -- and I've seen painters who'll turn their portraits upside-down, to get a fresh eye on it, and see -- just look at it in a new way, and force their brain to process it in a new way. And they'll see something in the painting that they were missing, even though it was right in front of their face.

Just because video games involve now hundreds of people, and millions of dollars, and years of time, it's equally true! Ultimately, they are a creative endeavor, and all of those human limitations of perception and thinking apply.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like