Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

“Progress” has almost become a buzzword in today’s gaming industry. And indeed the idea is of fundamental importance for the motivational power of gameplay. This article takes a critical look at the different forms of progress you may come across.

Especially in light of today’s wave of “free-to-play” releases and them usually offering buyable in-game progress, the implementation of progress systems has become a frequently discussed game design topic. A number of companies and researches try to answer the question of how quickly players should be able to advance to maximize their engagement. Scheduled rewards, among other factors, are introduced to inform players of their advancements to, ideally, make them “play forever” and motivate them to invest time (and sometimes money) again and again. Motivation itself being of utmost importance for any game though, is not a new and by no means a “free-to-play”-exclusive idea. FarmVille needs to motivate its players just as much as Starcraft, Chess or Tennis does. Otherwise the games won’t see any play and will, after all, simply be irrelevant. However, the occurring forms of progress are quite different in any particular case. Therefore the following article will take a close and critical look at each one of them.

The most obvious form of progress is immediately visible given a specific game state (therefore explicit) and at the same time aimed at an achievable endpoint, a static goal. Games primarily structured around this form of progress are usually meant to be solved, to be “finished”. Generally these titles are not concerned with replayability but experiencing the contents. They are “content-based” and thus exhaustible. The sequence of events and levels is preset by the creators. Therefore, at any given moment, the designer knows what situation the player will be in or at least which specific game states are possible. The interestingness of these static games can’t emerge dynamically and is instead purely handmade.

Many players appreciate this focus on this maximally engaging flow of events, even if it’s usually only meant to be experienced once. Others criticize the nature of these types of games as “disposable products”. Judging a work by its creator’s intentions however, the latter is only a valid complaint if the games are not designed to be “interactive stories” or “puzzle collections” to begin with. For example, Heavy Rain (with its story serving as a progress system) was never intended to be played multiple times. Therefore not offering enough replayability is not an inherent flaw of the game. Portal (with its combination of story and a linear sequence of puzzles) lives by the interestingness of finding the solution. Once found however, it’s naturally not exciting anymore. That’s not a problem either. Content-based games that are at the same time on the verge of offering dynamic gameplay challenges however, like Mass Effect with its combat system, are a different beast. It can be inferred that the designers wanted the player to at least put some thought into tactical and strategic decision-making. However, the overall linearity of the game directly undermines this intention: If the player is for example forced to repeat a battle multiple times, memorization of the exact sequence of events will inevitably take the upper hand. In the end, it becomes a (solvable) puzzle by accident.

Another clear example for explicit static progress is Super Mario Bros. with its completely transparent level structure. Monkey Island on the other hand combines story progress with an at times rather loose composition of puzzles spread over the game world. Even the single-player campaign of an RTS like Starcraft presents its players with a linear story and a set order of missions. In all these examples it’s immediately visible how far the player has come. The progress can be expressed in very precise, concrete and easy to understand ways: “Level 7”, “Mission 23”, “Scene 182”, “right after Jim died, “at the rubber chicken puzzle”.

Another clear example for explicit static progress is Super Mario Bros. with its completely transparent level structure. Monkey Island on the other hand combines story progress with an at times rather loose composition of puzzles spread over the game world. Even the single-player campaign of an RTS like Starcraft presents its players with a linear story and a set order of missions. In all these examples it’s immediately visible how far the player has come. The progress can be expressed in very precise, concrete and easy to understand ways: “Level 7”, “Mission 23”, “Scene 182”, “right after Jim died, “at the rubber chicken puzzle”.

A game based on story or pre-designed levels can be “beaten”, thus effectively nullifying any progress made (in the context of the game system). This is, regarding these indicators of static progress, also true at any point in the game. The progress made up to this point does not matter for the rest of the game. Persistent progress is, in contrast, of permanent relevance. It endures way beyond its acquisition, sometimes (although not necessarily) even beyond the “end” of a game, if it has one, and into another playthrough.

Typical examples include “RPG elements” like experience points and levels (Diablo, Dragon Age, FarmVille) or unlockables such as special abilities (“skills”). Once acquired, they become a permanent part of the gameplay system and affect its future dynamics (that is, if they’re not “achievements” having no actual connection to the game). In that regard, an interesting observation, for example made by the Game Design Bookclub, is concerned with the difference between horizontal and vertical (explicit persistent) progress.

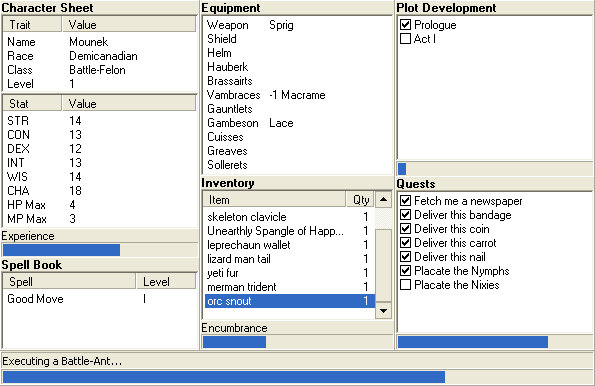

Horizontal progress, like unlocking new abilities, extends the spectrum (the “breadth”) of action alternatives for the player. Many primarily static games employ this form of progress to keep the game mechanics interesting long-term (Darksiders). Vertical progress on the other hand is basically increasing numbers. A classic example is the improvement of “character stats” (like strength or dexterity) in Diablo. This progress does generally not affect the possibilities the player has nor the nature of the gameplay system. Most of the time it only scales the effect of some specific actions, like more strength leading to more damage done by attacks.

Vertical progress is therefore in many cases the worse alternative. It is much less interesting than its horizontal counterpart because it does not present the player with anything new or interesting. Instead it usually just makes him fill bars. While this might feel just as good, it’s generally pretty meaningless for the particular system as well as the player and does not significantly affect the gameplay in any way (as demonstrated in the satirical Progress Quest). In many cases this form of progress is used to trick the player into believing that he himself has learned something. The urge to learn and master challenges (according to Raph Koster the root of all fun in games) is projected onto the virtual and numerical “learning” of the avatar.

Vertical progress is therefore in many cases the worse alternative. It is much less interesting than its horizontal counterpart because it does not present the player with anything new or interesting. Instead it usually just makes him fill bars. While this might feel just as good, it’s generally pretty meaningless for the particular system as well as the player and does not significantly affect the gameplay in any way (as demonstrated in the satirical Progress Quest). In many cases this form of progress is used to trick the player into believing that he himself has learned something. The urge to learn and master challenges (according to Raph Koster the root of all fun in games) is projected onto the virtual and numerical “learning” of the avatar.

On top of that, problems concerning the difficulty level arise: If the avatar gets stronger and stronger, the enemies have to keep up. However, the player should also feel more powerful over time (so the enemies have to grow in strength slower), but at the same time regularly face new challenges (so the enemies have to grow in strength faster). This conflict is usually circumvented by letting the game alternate between sections that are way too easy and passages that are genuinely difficult. This is usually a rather poor solution though, since the truly optimal composition (“flow”) of growing player capabilities on one side and more and more challenging gameplay on the other will rarely, if ever, hold up long-term.

Another part of the “progress machine” lets the player repeatedly execute low- to no-risk actions to gain an in-game advantage: grinding. Effectively it serves as a safety net, allowing the player to trade time for decreased difficulty and potentially make the game infinitely easy. While this may seem like a neat idea at first sight, it actually just means that the designer did not really finish his job. Instead of providing the player with a set of well-balanced and thought-out difficulty levels, the player himself is supposed to do this work and ask the question: “Exactly how easy do I want my game to be?” The player is supposed to decide at which of the (practically infinite) difficulty levels he will have the most fun. This means that he spends hours upon hours, grinding, to merely adjust the difficulty. Oftentimes games try to distract from what’s actually happening by drowning the player in spectacle and compliments such as shiny bars filling up, huge effects during combat and whatnot.

Even worse though, players regularly reach the conclusion that they should simply make the game as easy as possible through grinding. The reason is rather obvious: Grinding is in most cases the optimal strategy. The player continuously gains advantages without having to invest resources. There is no drawback to be feared. It is therefore the maximally safe way to success. In the context of the game alone there is no argument against grinding. A possible objection at this point might be: “But nobody does that if it takes so long! You don’t have to do it after all!” The problem is that this argument implicitly includes a transition to a meta-level of discussion and thus takes a step outside of the game. On the level of real life, there does exist a resource you have to invest after all: the time you have left to live. This resource only exists outside of the game though, and the player does not receive any real life value in return for investing it. The reward for grinding is purely extrinsic.

Even worse though, players regularly reach the conclusion that they should simply make the game as easy as possible through grinding. The reason is rather obvious: Grinding is in most cases the optimal strategy. The player continuously gains advantages without having to invest resources. There is no drawback to be feared. It is therefore the maximally safe way to success. In the context of the game alone there is no argument against grinding. A possible objection at this point might be: “But nobody does that if it takes so long! You don’t have to do it after all!” The problem is that this argument implicitly includes a transition to a meta-level of discussion and thus takes a step outside of the game. On the level of real life, there does exist a resource you have to invest after all: the time you have left to live. This resource only exists outside of the game though, and the player does not receive any real life value in return for investing it. The reward for grinding is purely extrinsic.

The demands of the player in real life and in-game are thus in conflict: In the context of the game, grinding as much as possible is clearly a great strategy. In real life however it’s agony best avoided (by the way, this is why the “free-to-play” business model works so well: it allows players to pay to skip the grind). The resulting mental dissonance and the stress of actively having to decide against the best in-game action should never be put on a player’s shoulders. Depending on the personal circumstances it can even lead to players maximally exploiting every possible bit of grinding in a game and therefore wasting countless hours of their lives, just because the game tells them that this is the optimal way to do things. A behavior that is in itself boring and uninteresting should never be part of a good, let alone optimal, strategy. The game design has to take counter-measures to prevent that from happening. As just one example, many roguelikes combat the limitlessness of grinding by using a “food clock”, i.e. letting the player’s avatar starve to death if he doesn’t move on to more dangerous and interesting levels quickly.

Besides explicitly visible progress there’s also a less obvious form: the player increasing his own skill. Games that primarily rely on this form of progress are usually played in matches (Chess, Spelunky, Auro, multiplayer Starcraft). Persistent progress is, if existent, usually only relevant for the duration of a single match. Most of it happens inside the player’s mind though, as he masters the controls over time or learns to understand all the strategic intricacies of the system. While gaining competence the player traverses one layer of mastery after another. James Pau Gee writes about the “Achievement Principle” in What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy:

“Good video games reward all players who put in effort, but reward players at different skill levels differently. [...] Good video games give players better and deeper rewards as they continue to learn new things as they play (or replay) the game This means that, in a good video game, the distinction between learner and master is vague (at whatever level of mastery one thinks one has arrived).”

Good games therefore force the player to question the gameplay routines he has gotten used to before, sometimes to alleviate them and use them as a working part in building a higher level strategy, and sometimes even to discard or reinvent them altogether. In any case, the game does not need explicit rewards if its gameplay is intrinsically interesting. In multiplayer games following this principle usually comes down to finding an opponent that roughly matches one’s own level of skill. In single-player games a well thought-out system of adaptive difficulty might be the corresponding solution. Of course, introducing a set of selectable difficulty levels can do some work, too.

Good games therefore force the player to question the gameplay routines he has gotten used to before, sometimes to alleviate them and use them as a working part in building a higher level strategy, and sometimes even to discard or reinvent them altogether. In any case, the game does not need explicit rewards if its gameplay is intrinsically interesting. In multiplayer games following this principle usually comes down to finding an opponent that roughly matches one’s own level of skill. In single-player games a well thought-out system of adaptive difficulty might be the corresponding solution. Of course, introducing a set of selectable difficulty levels can do some work, too.

It’s important to note that merely increasing the victory requirements numerically while keeping the system exactly the same is not enough. Especially the highscore model in single-player games comes with some inherent problems: For example, if there’s any randomness involved the game will come down to restarting and waiting for a particularly favorable run. Furthermore, by steadily increasing the highscore the game in a sense becomes “unwinnable”. At the very least topping the previous best attempt becomes a very rare occasion, which certainly does not correspond to increasing skill in any way. On top of that matches with particularly high-reaching scores usually last longer and longer, thus disregarding that every game has an optimal match length based on the length of its strategic arcs. And at last, risk management becomes a triviality in a highscore game. If the goal is merely to get the “highest score ever”, then it’s obviously optimal to simply maximize every possible risk.

In practice all the forms of progress mentioned in this article do not always come as clear-cut as they have been described here. Heavy Rain features mostly static, FarmVille mostly persistent and Outwitters mostly implicit progress. But even in the case of Super Mario Bros., besides the linear sequence of levels there’s also the skill of the player involved. Looking at Diablo 3, one can find an even more complex situation: Story meets quest structure, vertical (stats) progress meets horizontal (skills) progress, and even player skill does, if only marginally, influence the system. While the story does not interfere with the implicit progress too much, the explicit persistent progress certainly does: When receiving positive feedback from the system, it’s usually not clear if the player himself has actually gotten better, or if his avatar is merely more powerful, or in case of a combination of the two how much each side has exactly contributed. Hence the transparency of the system suffers. Also, the level of challenge is, as mentioned before, oftentimes tuned suboptimally.

After all, the different progress systems can get in each other’s way. A linear story or level structure is of questionable value for a system of implicit skill-based progress. It’s of fundamental importance for the latter to allow for potentially endless replayability and mastery. A static, exhaustible game however is specifically designed to be experienced once. Both of the explicit forms of progress (static and persistent) on the other hand, go together decently well: While a story is told, new gameplay mechanisms can be introduced without problem (Ocarina of Time). Ideally both progress are closely intermeshed to guarantee an especially strong boost of (extrinsic) motivation.

After all, the different progress systems can get in each other’s way. A linear story or level structure is of questionable value for a system of implicit skill-based progress. It’s of fundamental importance for the latter to allow for potentially endless replayability and mastery. A static, exhaustible game however is specifically designed to be experienced once. Both of the explicit forms of progress (static and persistent) on the other hand, go together decently well: While a story is told, new gameplay mechanisms can be introduced without problem (Ocarina of Time). Ideally both progress are closely intermeshed to guarantee an especially strong boost of (extrinsic) motivation.

Whatever forms of progress you may find in or design for any particular game, be wary: Do they pursue conflicting goals? Or can they co-exist peacefully? Maybe they can even support each other: Imagine using a (static) story-based mode to introduce your theme and mechanisms one-at-a-time (horizontally), and then switching to an “evergreen” match-based mode of pure skill later on. The fact that many players like ever-increasing character stats, others want to play through a story and some are aiming to challenge their own capabilities, is not a reason to put all of them into one single gameplay experience. Maybe that way everyone will find something to like but probably no one will really like the overall result (imagine a “one size fits all” glove). Any form of progress should instead have a good reason to exist in a specific game design.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like