Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In a wide-ranging article, former Company of Heroes: Opposing Fronts narrative designer Stephen Dinehart looks at the future of game story by examining narrative theory through the ages.

[In a wide-ranging article, former Company of Heroes: Opposing Fronts narrative designer Stephen Dinehart looks at the future of game story by examining narrative theory through the ages.]

What is the future of video games? This is a large, if not insurmountable question, especially when considering the increasing diversification of styles within the medium. Indie, casual, core, mature -- the labels continue to proliferate, identifying specialized niches of styles, however real or unreal, within the larger medium.

Forming at present is a new niche, one that threatens to pull away from the classic play-centric design paradigm. It's forming in the cubicles over at Visceral, at BioWare, at Ubisoft and at 38 Studios.

Many studios are aiming with different titles and terms, but the goal is to transplant the player into the video game by all means of his visual and aural faculties -- into a believable drama where he is actor. This is dramatic play; interactive drama that utilizes interaction, rather than description, to tell a story.

Aristotle began the movement some 2300 years ago with his Poetics, dissecting plays into clear parts and functions [Aristotle 330 BCE]. Some 2000+ years later, Richard Wagner saw a dissolving of the fourth wall of theater, bringing the audience into the play as actors so that the stage art may breathe like life, and seemed to them to be as expansive as the real world [Wagner 1859].

Through the next 130 years various studies and pioneers would set out on a pursuit to hit that mark: happenings, video installations, virtual reality, just to name a few. Though the target was never reached and the pursuit itself seemed to fall into the land of the obscure, and intellectual, without much effect on the everyday life of the public and how they experience stories. With the dawn of popular video game culture, the pursuit has gained a refined focus.

Janet Murray described how it would feel in Wagner's world of immersive interactive story [Murray 1998], and most recently Michael Mateas with his creation Façade and the accompanying paper Interactive Drama, Art, and Artificial Intelligence set out a detailed approach to creating dramatic systems [Mateas 2002].

This seemingly obscure pursuit has leaked, via some osmosis, into contemporary AAA video game development, manifesting in such titles as Jade Empire, Dead Space, Far Cry 2, World of Warcraft and the author's own Company of Heroes.

These games seek to immerse the player in a dramatic role play, whereby they assume the role of character in a different time and place, and whose actions and presence having meaning in the world as designed.

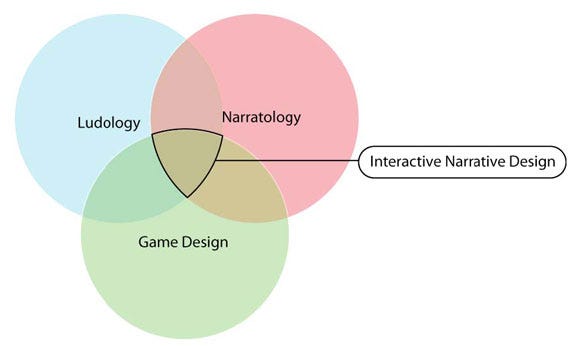

Dramatic play is the new niche these games expound upon, a paradigm that is the focus of interactive narrative design, a craft that meets at the apex of ludology and narratology and conjoins the theories into functional video game development methodologies (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Interactive Narrative Design

Ludology is the theory of play commonly used by contemporary game makers in the pursuit to understand and craft interactive systems. Play is defined as "movement within a system" [Salen, Zimmerman 2003].

Narratology is the theory of narratives, which is utilized by writers, critics, and academics, to understand the parts and functions of narrative texts, cultural artifacts that "tell a story" [Bal 1994]. Narrative is dramatic text that engages the reader in a pattern. Interactive narrative is a dramatic text that engages the player in a meaningful participatory pattern.

The game system fires up, the cooling fans roar, and the once-black screen ignites. Immediately the player engages the video game and encounters stimuli: text, main menus, loading screens, cinematics, play mechanics, player characters, non-player characters, etc. They take witness and navigate the system using designed actions, play mechanics.

Using these mechanics, the player acts as an agent within the participatory dramatic spectacle. An agent is a person or thing that takes an active role. The player moves forward through a series of events acting with designed mechanics to bring about change in the system in order to achieve some desired outcome.

To act is to cause or experience events. An event is a transition from one state to another. As a player acts he assembles a series of logical and chronologically related events, a fabula. This is the story, a series of events cognitively assembled and perceived by the player. The player authors this through the reading of the text.

"A narrative text is a text in which an agent relates a story in a particular medium," [Bal 1994]. The video game is related, or narrated, by the video game engine to the player through both active and passive means.

Text, imagery, feedback, sound, and temporal sequences are read, perceived and judged. The game engine presents a narrative text to the player and says read me; understand what I am; and immerse yourself in the simulation.

Some are better readers or better players, but all the players read and absorb the experience. As the player progresses in his play these judgments about the events, experienced as a result of his actions, cause him to modify his play to produce desired results.

Reading allows the player to determine the next action needed to achieve a specific objective, or "object of desire". The story is needed by the player to convey the subjective meaning associated with the narrative read in the video game. A dramatic pattern that when assembled by the player creates a [player] story; a communication about the way things are within a particular system.

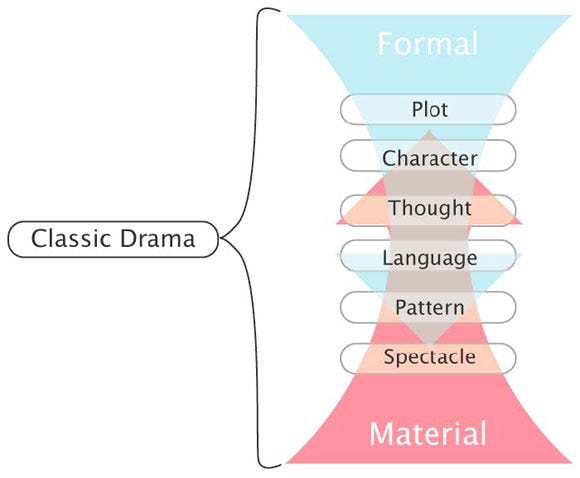

Aristotle's Poetics is a classic text that was the first to identify clear patterns and structure in narrated stories. The narrative design system of six hierarchal categories serves as both a tool for storytellers and critical study: Plot, Character, Thought, Language, Pattern, Spectacle -- the parts of a play. These all are related by formal and material causes (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Classical Dramatic Theory

Material cause is the material with which a spectacle is created; a formal cause is the "object of desire" (desired outcome) toward which a plot is headed. The plot is a constructed series of events by which a writer tries to expound on a theme.

The characters are formally caused by plot; the characters in turn are formed by their thought, the first step in creation. This thought translates to language, which within a temporal period becomes a dramatic pattern that forms a spectacle, caused by the actions of characters.

The material cause works in reverse moving the audience from spectacle to plot. When a drama is successful the audience experiences catharsis, a realization of the formal causes of a spectacle, the ever elusive "a-ha" moment, which is so often missed and misunderstood. This constructivist system attempts to dissect how both the audience and writer to understand the structure of drama.

With time the constructivist approach evolved further. Vladimir Prop created a formulaic system to deconstruct the narrative systems of Russian fairytales [Prop 1968] He took texts and broke them down into formula of elements (variables, values, functions) that when read create a meaningful narrative. They could be mixed and remixed to create believable, albeit "unauthored", texts resembling the authored parents from which they were derived.

He worked backwards, starting with meaningful patterns, dissecting the texts to identify the narremes, parts and functions, fundamental to their narrative systems. Prop's dissection of fables further suggested that a constructivist approach to story was possible; it seemed system design was inherent to these stories.

One man's system has been the feature of many of Game Developers Conference lectures, Joseph Campbell's The Hero's Journey.

While a wonderful framework to understand the structure of myth, like Prop's, these systems were never meant for constructing stories, but to understand the structure of cultural artifacts, texts.

Narrative design works in the opposite manner. It is a narratological craft that focuses on the structuralist, or literary semiotic creation of stories [Dinehart 2008]. Narremes (variables, values, functions) are formulated into designed patterns to create a cohesive narrative structure.

Interactive narrative design works in a similar manner, creating parts and functions to design and develop interactive narratives systems; ones that deliver meaningful texts focused on core play experiences of a visceral nature.

The aim is to create a cathartic immersive interactive world with a meta, or arch, narrative facilitated through designed dramatic play.

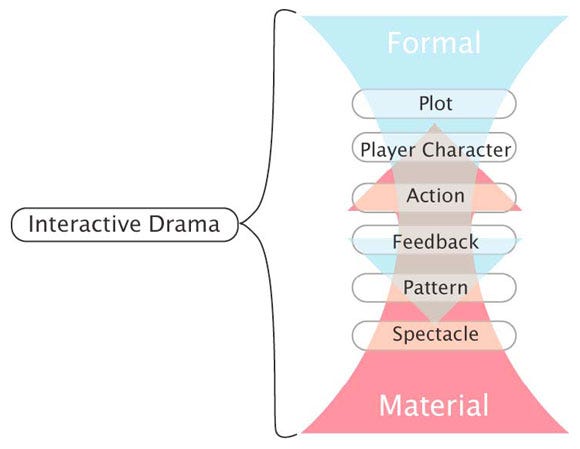

Similar to the neo-Aristotelian approach proposed by Mateas [Mateas 2002] the theory of interactive narrative presented here takes the narratological model of Aristotelian theory, and alters it with the considerations of ludology and AAA video game design. Here the plot is a constructed series of events by which an interactive designer tries to expound on a theme. The plot formally causes the player character (PC).

The PC is formally caused by their designed actions, the feedback produced by the system a formal result of player actions, this feedback loop forms a pattern, and this pattern forms a spectacle. Again here the material cause works in reverse moving the player from spectacle to plot (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: Interactive Dramatic Theory

Dramatic play systems invite the player to co-create a plot through a world that is influenced, if not shaped, by their actions. In this role play, the question is begged of the player "what kind of character do you want to be?" Begetting the formation of a particular desire in the player, a desire to be. By actively pursuing that desire, the player becomes an active protagonist.

In taking action, trying to achieve that character, to be the person he desires, conflicts naturally emerge. As Robert McKee would have it, the "gap" opens up. That is the gap between what is in actuality, and the goal of achieving what is desired [McKee 1997].

It is in this basic human conflict of wanting we have drama. Drama is a serious play of human conflict. Interactive narrative creates more engaging game conflict. Conflict which plays on a players own desires to act and achieve; engaging the player in a participatory dramatic pattern that is focused on a concise themed communication.

Interactive narrative design is a craft that aims at creating dramatic play systems. Systems that deliver narremes, narrative elements, to a player so that they may cognitively craft a story based on their navigation within said system. When successful the player authors a plot-driven text based on their experience within the played video game.

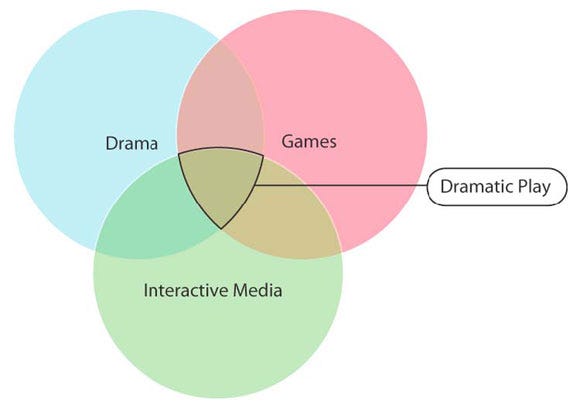

Figure 4: Dramatic Play

While the aims of interactive narrative design are similar to game writing and game design, and surely involves many of their crafts, interactive narrative design makes story to take center stage so that the systems engaged by the player are delivered in continuity with a core thematic vision [Dinehart 2008]. This is surely a both present and future art, a fusion of drama, games ,and interactive media, one that is here called dramatic play (See Figure 4).

The video game industry now stands on a threshold, ready to create a new form of story -- an interactive one. As video game products increase in diversification that new form exists, forming a yet to be named niche within the medium whose aim is dramatic play.

It is at the intersections of interactive media, games, and drama that dramatic play exists. It's been a long time coming; for over 150 years people have been trying to bring it forth.

Heralding it most was Richard Wagner, ever famous German composer and theorist. He called this new form "Gesamtkunstwerk", or "the total artwork", the embodiment of all the arts into one fusion in which the fourth wall [screen] is dissolved and the spectator becomes actor-player.

Drawing from an adapted definition of his total artwork, the Gesamtkunstwerk is described as the artwork of the future, a work that transplants the player into a dramatic space by all means of his visual and aural faculties, making one forget the confines of reality; to live and breathe in the drama which seems to the player as life itself, and on in the work where seems the wide expanse of a whole world [Wagner 1859]. The key to this dramatic play is the craft of interactive narrative design.

As the videogame industry slowly changes to see interactive narrative as a viable enterprise it will beget the total artwork of the 21st century, dramatic play. Or as Dr. Greg Zeschuk of famed narrative-driven developer BioWare put it recently, at the GDC Canada conference, "What [video games] are going to be in the next 30 years is limited only by, we think, the imagination... We're the creators; it's an exciting role to have. Narrative is one of the most powerful forms of expression," [Remo 2009].

1. Aristotle. Poetics. 330 BCE

2. Wagner, Richard. The Art Work of the Future. Kessinger Publishing, 2004.

3. Zimmerman, Eric and Salen, Katie. The Rules of Play. MIT Press, Cambridge MA 2003

4. Bal, Mieke. Narratology. University of Toronto Press. 1994

5. Mateas, Michael. Interactive Drama, Art, and Artificial Intelligence. 2002

6. Murray, Janet. Hamlet on the Holodeck. MIT Press, Cambridge MA 1998

7. Propp, Vladimir. Morphology of the Folk Tale. University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas 1968.

8. Dinehart, Stephen. "Defining Narrative Design". The Narrative Design Exploratorium 2008.

9. Mckee, Robert. Story: Substance, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting. Regan Books, 1997.

10. Dinehart, Stephen. "Defining Interactive Narrative Design". The Narrative Design Exploratorium 2008.

11. Remo, Chris. GDC Canada: Bioware Bosses Talk The Future of Storytelling. Gamasutra 2009.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like