Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Bethesda's Emil Pagliarulo and 2K Marin's Jordan Thomas discuss the importance of building challenging, satisfying ethical gameplay -- both in their games and in the work of others.

[Gamasutra interviews Bethesda's Emil Pagliarulo and 2K Marin's Jordan Thomas to discuss the importance of building challenging, satisfying ethical gameplay -- both in games the duo created such as Oblivion, Fallout 3 and BioShock 2, and in the work of others.]

To a certain degree, all games are about choice. The player chooses how and when to react to a given situation, whether that situation is as simple as fight or flight or as complex as determining the future of an entire species. Given the role that choice holds in gameplay, it's no surprise that morality systems have become more and more common as games have increased in complexity.

Oftentimes these morality systems offer up only basic black and white choices: should I help this character or harm them? Should I defeat the evil wizard or accept his offer of power? Various types of moral choice systems appear in complex RPGs like Mass Effect 2, adventure games like Heavy Rain, and even straightforward action titles like Dante's Inferno.

Compelling moral choices can encourage players to experiment with different ethical stances over multiple playthroughs, while underdeveloped morality systems can seem like little more than an additional bullet point on the back of the box.

To examine how to make in-game moral choices that are both intellectually engaging and stimulating from a gameplay perspective, we spoke with key developers from two studios with very different specialties: Bethesda's Emil Pagliarulo explained how he and the rest of the team approached morality in RPGS like The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion and Fallout 3, while 2K Marin's Jordan Thomas discussed branching moral outcomes in the shooter BioShock 2.

The results of the conversations with the developers pointed to two aspects that need to be present in order to make in-game moral choices compelling: a virtual world that somehow connects with the player, and a set of choices that offer outcomes of significant moral weight.

The two required elements may seem obvious, but more often than not a game with a moral choice system is missing one or the other. Choosing to punish or absolve tormented souls in Dante's Inferno carries no weight because it has no connection to the narrative -- it's all about maximizing what kind of experience points you want to earn. InFAMOUS features a likeable protagonist and a recognizable world, but the choice to give food to hungry citizens or keep it for yourself is no choice at all in a game that doesn't require you to eat.

So how do developers tackle the issue? The first step is to create some element that players can create an emotional bond with. "It all comes back to the characters you've created," says Bethesda's Pagliarulo. "I think Heavy Rain has proven this better than any game in recent memory. In order for a developer to provide moral choices that matter, the player has to be convinced that those choices are going to have some kind of effect on the characters in the game, and the more believable those characters, the stronger the emotional impact.

"At the end of Heavy Rain, if there's one thing you feel it's that Ethan loves his son and is completely invested in finding him, and this really challenges the player's willingness to go as far as it takes.

"As it turns out, when I played Heavy Rain, I wasn't willing to do carry out one of the sequences, and I actually sat there yelling at my TV, saying, 'No! I won't do it! This isn't my fault! I will not be made the bad guy! You stole my son -- it's your fault! Not mine!' I was pissed off. Not at the developers, but at the Origami Killer. And you know what? The game didn't exactly have a happy ending."

Few games have managed to create the same kind of believable characters as Heavy Rain, but fortunately there are other ways to draw a player into a game. One of the strongest elements of the original BioShock was the city of Rapture, a game world that was so solidly drawn that it felt real. It had a history, a set of rules that it adhered to, and an internal ecosystem that made it feel like a real place.

BioShock 2

"A lot of people told us that in their version of the world, they decided not to kill Big Daddies," says 2K Marin's Thomas. "This is not an outcome we support with any special content. This is a simulated moral decision that they chose to make based on their own level of empathy for these enslaved former humans."

The world of Rapture in both BioShock games is a place founded on debatable concepts, and both games use a clash of ideals as the basis for the narratives. Rapture is both physically and ethically murky, and as such clear-cut "good and evil" choices seem out of place. In Rapture, the choices should be every bit as unclear as the rest of the world, something which Thomas believes the original game failed to achieve:

"It chose a very binary set out outputs at the far end," he says. "The players who enjoyed that were those who kind of were those who felt that they were embodying a moral extreme anyway -- there was a sort of cogency between what they chose and the outcomes they received. The ones who were less satisfied felt that they were morally more grey, or granular, and as such neither of the endings of that game reflected them well."

In other words, the players who felt as if they were playing a purely good or purely evil character were satisfied with the two possible outcomes, but those players (arguably the majority) who viewed the BioShock experience as more morally ambiguous were less than satisfied with the simple either/or choices.

In the case of BioShock 2, the solution was to strive for moral choices that were a bit harder to read as obviously good or evil. "BioShock 2 is, at best, a modest stride forward in the shooter space in the introduction of some RPG-like branching moral choices through the filter of parenthood," says Thomas.

"Our choice there was to refract rather than reflect. Your choices have a strong effect on your legacy, but your sense of powerlessness over that legacy once it kind of decouples from you was in many ways the point. We felt that there is no actual way to know the player's mind utterly, and so to instead use his or her behavior as a set of guidances was more attractive and more honest, particularly because we wanted the choices to be very readable even to a player who may have been in a firefight when all the seed choices took place.

"You're always kind of competing for the player's attention in the shooter space, so the inputs and the outputs had to be obvious," says Thomas. "So we chose this alternate vehicle to refract the outcome of your choices as a response to the relatively feeling of dishonesty that moral branching narrative can invoke elsewhere.

"We've been successful in some ways -- some critics seem to have bought into that sense of their moral legacy rather than exact reflection. Then you've got other folks who felt more like 'Hey, I wanted Lamb to die at the end and it didn't work out that way! This game is silly.'

"I think of it very brutally as baby steps in the sense that in the first game, your moral choice was cognitively quite juvenile: are you going to mistreat the innocent for your own gain, or are you going to redeem that innocent, even though you sacrifice something for it?" continues Thomas. "In BioShock 2, we said, let's introduce a set of points which are couched more in the adult world and about context rather than action.

"The moral choices in BioShock 2 remain interactively very simple - we debated whether we were going to go with a complex quest which had a very different outcome depending on which set of widgets you flipped, and we realized that the result wouldn't be very visceral - the player's inputs in a first-person shooter are largely different ways to deal misery. And having to flip a bunch of different switches, in order to achieve a kind of dissociated, broad world-spanning moral result would feel kind of dry, kind of academic.

"So instead we tried very hard to follow our own set of rules, which are quite narrow in the shooter space, and to preload you with as much context as possible before you had to make that decision. Each one was meant to be ethically murkier as you move towards the conclusion.

"So early on, Grace has clearly misunderstood your intent; at the end she has many sympathetic attributes. When dealing with Dr. Alexander, you're in a space where one version of this character is asking you to execute his final will and put him out of his misery, but the actual living being in front of you is begging for his life and has obviously shown enmity towards you. Showing traditional mercy in that case is quite debatable."

Choices that are deliberately harder to read as simply the "good choice" or the "evil choice" were a goal for Pagliarulo in both of Bethesda's most recent RPGs as well. Of course, successfully creating tricky choices doesn't always come easily. "That was a real challenge for us during development of Fallout 3," says Pagliarulo. "We actually started out much more comfortable with having just those black and white, good and evil choices.

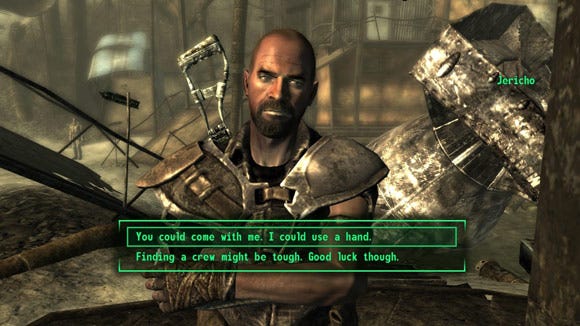

Fallout 3

"You have to remember that we weren't just trying to make a great game, we were trying to make a great Fallout game, and we struggled sometimes with the best way to pull that off. The previous Fallout games used a karma system to keep track of the player's level of good or evil, so we knew that's something we wanted to replicate. It was a good place for us to start. But then, as we got deeper and deeper into development, and really started to find our comfort zone, we realized we were missing that grayness, that moral ambiguity that is so important to the Fallout universe.

"I think, when all was said and done, we were happy with the mix Fallout 3 offered. There were some clear good/evil paths, and the player could make those easy moral decisions, and sort of try to get those karma-specific level titles, or achievements, or be treated a certain way by the various factions. But there are also plenty of situations where it's much more morally nebulous, and the player is left wondering, 'Is this the right thing, or the wrong thing?' I think the ending of The Pitt DLC sort of exemplifies that."

Unlike most games with a morality system, Fallout 3 had the extra challenge of creating a neutral moral path, which had its own unique set of challenges. "This was the subject of much debate during Fallout 3's development," says Pagliarulo. "Really, the biggest issue for us was deciding, internally, whether something was right or wrong! The designers ended up debating certain issues, and we came to realize just how differently we all viewed them.

"For example, a couple of us would come up with a situation that wouldn't give the player any positive or negative karma. We felt it was pretty morally ambiguous, a good 'gray' neutral point. And then we'd bring it up in a meeting, and another designer would say we're crazy, and it's clearly good, or clearly evil. And we'd disagree. It was great... and so completely unexpected.

"So for us, because we had a system to track activities that are supposed to be clearly good or evil, the real challenge was in us coming to a consensus on this stuff. Is making a kid cry evil, or just funny? Some of the conversations we had bordered on the ridiculous, in retrospect."

As with any debate on ethics, there are several different takes on what makes for compelling moral gameplay, and both Pagliarulo and Thomas can cite several examples about what makes for interesting gameplay choices, as well as why it's become popular to give gamers these options.

"I think gamers get tired of doing the same thing over and over," says Pagliarulo. "We've slain dragons, beat up super villains, and shot at space marines over and over again. There's a level of burnout there. So when you throw in something like a morality system, it forces the player to stop running on autopilot, and think about their actions a bit more carefully. 'Shooting the bad guy' becomes 'shooting the guy who may or may not be bad,' and that in itself adds a unique twist to the gameplay.

"Look at a game like Army of Two: The 40th Day. You've got this really tight co-op experience, but there are also these situations where you've got to make a moral decision in a matter of seconds. You never know when one is going to pop up, or what the outcome is going to be, and it adds a layer of gameplay beyond simply 'point my gun at this guy and pull the trigger."

Thomas points to studios like BioWare and Pagliarulo's employer Bethesda as developers who create games with compelling choices.

"There were quests in the Baldur's Gate series which I felt were sort of difficult for me to reconcile because there wasn't really a right answer," says Thomas. "The choices you made would offend a party member and that party member, when pushed to a certain limit, would turn on you.

"I experienced a kind of crisis in that I wanted to please everybody, and I certainly have seen a lot of real-life humans fall prey to that same problem. Ultimately, it felt as subjective and kind of relativistic as philosophy does in real life. At that moment I was like 'dammit, there's no right answer here!' and of course I had to put down the party member and felt terrible about it."

"Then there's the assassin's guild quest line in Oblivion, written by Emil," says Thomas. "It's very interesting, because it's supposedly the most kind of sociopathic and empathy-free quest line in the game, and yet it's also the one that made me feel something. Because -- spoiler alert -- you're brought into this quite charming family of monsters and at some point you're called upon to turn on them and kill each one through a variety of means - poisoning their food, killing them in their sleep, all of these things.

"You come to sort of love them, because they're charming in their sort of gruesome fairy tale way. And so I felt genuine ethical queasiness at the prospect of taking the few characters in the game that I cared about and annihilating them for the cause."

Finally, Thomas points to Ubisoft's open-world shooter Far Cry 2 as an unsung example of a game that offers compelling moral choice gameplay. "There are certainly decisions that you can make that shape the narrative in a very broad way, such as when one of your rescue-ready buddies comes out to help you in the field. If they get tagged and they're bleeding on the ground, you can sacrifice one of your syrettes to bring them back, but if you can't do that you can either abandon them or blow them away.

Far Cry 2

"All of these things feel grey when they're in the heat of the moment. They're contextual. The game responds to them, but it's not really making a specific didactic moral statement, it's just putting you in the position of making interesting decisions and allowing your own pre-loaded moral structures to be self-applied. I think that's extremely powerful."

As designers continue to experiment with interactive morality, new innovations will certainly arise to allow for more and more powerful emotional experiences. Could the first step towards creating more moral complexity be the discontinuation of rewards like Achievements and Trophies for earning the "good" or "bad" ending of a game?

"You could argue, and I think many have, that moral decision making in interactive entertainment sort of requires that you accept the sociopathic economist in all of us," says Thomas. "If you want to players to make these decisions based on any kind of internal ethical compass, you should decouple them from any mechanical rewards. I'm not totally sure I agree with that, because in real life, there are physical rewards for all forms of self-interest. But I certainly agree that we start with such an incredible bias upon entering a genuinely solipsistic artificial space."

"Concrete gain is the root of any conflict of interest," Thomas continues. "It's difficult to imagine a set of quandaries that doesn't touch on material. I know that you can do it, but you would be filtering those questions, and perhaps in some game where all rewards are essentially equal.

"Perhaps it's also possible that you'd have to open up to leaving things in a state of questionable resolution as well. In BioShock 2, as a highly narrative-driven shooter, we felt compelled to tie it off, to show that your actions lead to a dramatically compelling outcome no matter what. In real life, that's not the case. The right path might actually be the most boring. There's the notion that we're also entertaining as we do this.

"That puts the thought experiment of what games could be into some question. Because again in the case of BioShock 2, we're throwing millions of dollars at this, and the user is expecting to be compelled and titillated in the same way as with any narrative. And as with real life, playing the saint is a lot less fun and arguably not a commercially viable decision."

While Thomas is probably correct that few players will say they want to be all good all the time, the feedback on moral choices in games might suggest otherwise. In short, although many games offer up the option to be diabolically evil, most players want to be good. "Interestingly, when we looked at the actual stats for Fallout 3 we learned that a really staggering majority of people chose to play the game as the good guy," says Pagliarulo. "So it's really interesting to me that even though we gave players the choice to be evil, to be the jerk -- most of them chose not to."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like