Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

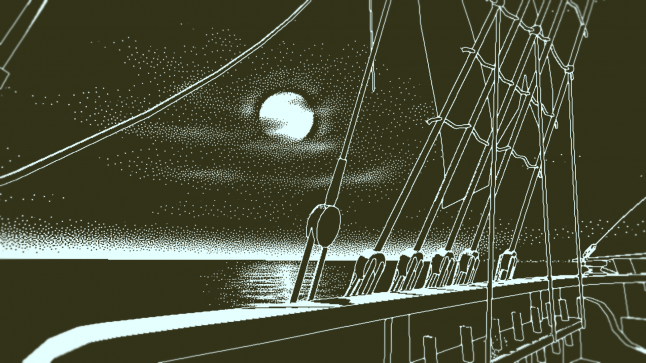

Having played Return of the Obra Dinn recently, I was inspired to write about historical settings, exploring themes, co-linear storytelling, and ships - all within the context of the Obra Dinn.

(NB: this was originally posted on medium)

There’s something that draws a particular kind of writer to ships.

Say we want to create a story - a story not about a particular character and their journey, but a group of characters. This group cannot be homogeneous or united in purpose, as the story is not about the group’s journey together, but about the lives of each individual, and how they each bounce and reflect off of each other, just as our real lives do. In life, each of us is the hero (or at least the protagonist) of our own story, and we have scant opportunity to fully see or comprehend how we affect the other people in our lives, much less the effect of our bit parts in the lives of acquaintances or strangers.

Back to our story. We need to have some way to bound the scope of the narrative; a defined span of time that our characters’ stories play out in, bounded by significant events, along with a clever constraint to stop ourselves linking ever more relationships (and thus characters) into our tale’s deliberately tangled web.

Oh, and to reduce the complexity of the backstory, let’s ensure that there are at least several distinct groups among the characters that don’t know each other when the story starts, so that a reader can meet each of our characters through the eyes of another. (These groupings will also make it easier for the reader to remember each character among the ensemble.)

A journey on a ship, preferably in a time before modern communication technologies, fits all these criteria perfectly, and it’s how you end up with, say, Katherine Anne Porter’s fascinating 1962 novel Ship of Fools. The setting is a 27-day voyage from Mexico to Germany in the early 1930s, and throughout the novel she continually dips into one character’s life, only to have them bump into another character, who we then follow until they encounter the next.

While Ship of Fools never lived up to the incredibly high expectations of the public - Porter was a renowned author of short stories and had famously been working on the novel for decades - it succeeds at portraying people that are, in Porter’s words, “alive and real”, through this format of interwoven, co-linear stories.

It’s this same goal that drives my current work on Wayward Strand, and could provide some explanation for the setting and perspective of Lucas Pope’s brilliant new game, Return of the Obra Dinn.

I played Obra Dinn this past weekend, and as soon as I finished it I couldn't stop thinking about it - its structure, its perspective, the stories it tells. I see a lot of similarities between what Obra Dinn achieves and what we’re trying to do with Wayward, and my brain’s been churning on many of these topics for actual years, so I wanted to get at least a haphazard collection of them written down somewhere.

(Note that the following may only make sense if you’ve already played Return of the Obra Dinn, or at least have an understanding of what the game is.)

Following a thread of untimely demises in Obra Dinn is a Memento-like experience: each scene contains clues or suggestions as to the next, and as you follow a thread back through time the story gradually unfolds, both forwards and backwards.

Something I find really interesting about these scenes is how minimally they are constructed. Oftentimes there are just a couple of lines of dialogue, sometimes even just a snippet of non-verbal audio (which tells its own grisly tale) - after it plays, the scene you are visually presented with and can walk around in is a single, frozen snapshot of a moment in time.

Thus, there’s a large amount of the story and plot which is inferred, or can be inferred, within the space that is propped up by these spare materials. It’s space in which you are meant to reason through various possibilities and develop your own timeline of events in order to solve the game’s puzzles, but in this space you can also develop characters further - you can fill in other events to satisfy your own curiosity or desire to have a more complete mental picture of what went on.

This method of storytelling gives the player’s mind lots to chew on during and after the actual experience, as well as providing the story a sense of a scale beyond itself. The implicit, grey-space elements that are created from the explicit scaffolding create an impression that there is more to what’s going on than just what you see or hear or even put together yourself; that the story that you are experiencing is happening within a larger context.

Why is that important to me, as a creator and as a player? I think it’s because so many narratives are so tidy and clean - they fit within a specific, heroic mould that is born of our individualistic society and is pleasurable to our pattern-sensitive brains - but that’s not how life works, at least most of the time, and stories told within that mould, while powerful, neglect so many aspects of real life that I think are important and exciting to explore in fiction.

When following a thread of these vignettes of death, while each scene focuses on a different character, the scenes often are co-linear within the timeline of the narrative. This allows the creator and the player to explore another common real-life occurrence that is rarely explored in fiction - several events that overlap messily with one another in time, the complex combination of these events affecting each individual in a different way, based on their perspective of the events, but also their own history and personality.

The rarity of this phenomenon in stories correlates with our limited understanding of it in our lives - and co-linear storytelling through interactive media is an exciting new way to explore it (this is also the case for several other real-life phenomena rarely explored in fiction).

One of the things I really enjoy when experiencing a complex, challenging piece of fiction - unfortunately a rarer occurrence when playing games - is realising key themes of the work only when thinking about it later. While producing a work that achieves this is admirable, for me it’s not really about the “genius” of the artist; it’s just a natural outcome of consistently thought-provoking work.

With Return of the Obra Dinn, what crystallised for me upon reflection is that the story and the experience is very much a meditation on death - not the dread of death, or the concept of death, but specifically the fact of death. The game is comprised of dozens of scenes depicting the exact moment that life, as we understand it, leaves the bodies of each of the ship’s inhabitants.

Through this meditation, it expresses the equity of death - it comes for everyone, and everyone is reduced to nothingness by it. It does this in concert with exploring the inequity of life, with POC characters scapegoated and executed for crimes they did not commit, or poor/lower class characters being assigned dangerous tasks at the whim of their masters.

It also feels like an exploration of a familiar paranoia around the particularities of death - a persistent feeling that our bodies are soft and delicate things in a world of sharp, heavy, fast-moving objects. How many times has each one of us been meters, cm, or mm away from our heads being squished, our organs poked, bodies torn apart, burned, drowned?

There’s a morbid satisfaction in examining and noting down the particulars of each death - it scratches an itch to further our understanding of death itself. (To try to avoid it, or to try to prepare for it? It’s not really going to matter after the fact.) In designing the puzzles within the game, it wasn’t strictly necessary to include specifying the exact cause of each character’s expiration, but it’s a critical element within the whole.

Over the past few years I’ve thought a lot (and spoken a bit) about the reasons for setting games within a real historical context, or at least a context that has a relationship with history or the current-day world, as well as my frustration with how few game makers even seem to consider a setting that isn’t fantasy or science fiction when creating their game.

Obra Dinn’s use of a specific historical context was a huge draw for me - it provides an agency to explore, through fiction, what the lives of some real people who did exist at some point in time would or could have been like - people who we have no real way of connecting with.

There were thousands, if not millions, of voyages like the Obra Dinn’s throughout the centuries in which sea travel was the only available option; few if any of those voyages were ever recorded in minute detail. (Absolutely none were recorded as an interactive 1-bit adventure through time.) Works like Return of the Obra Dinn are obviously not exploring what actually happened, but they give us a lens, in the current day, with which we can peer back into that time and place, to imagine, speculate and wonder.

When creating something set in real place and time, we take on a certain set of responsibilities. While we can add as many mystical creatures or Lazarean dirigibles as we like, the work will become a constituent piece of a player’s mental picture of that place, in that time period, in that situation, regardless of their conscious intentions. This creates a responsibility to consider how we present these places, these people, and their stories.

While Obra Dinn does include people of colour and several characters who are women, there’s no evidence, explicit or otherwise, of the existence of queerness in the lives of any of the characters depicted, at least as far as I could ascertain. I certainly understand and believe that in many cases, queerness would have to be hidden or obscured for the safety and survival of the individuals, and it would likely exist in different forms as compared to the modern day, but I believe that, in creating works that include large ensembles of characters in particular, creators ought to consider the the power and effect of a total exclusion of queerness in its representation.

The specifics of how you include it might be tricky and warrant research and consultation, particularly for creators that don’t identify as queer, but not including it is a choice, and will say as much (if not more) about what the work considers “normal” and aberrant behaviour, both now and throughout history.

This (hopefully constructive) criticism is really as much for me as for Obra Dinn - regardless of setting, I believe the default mode of writers ought to be thoughtful and inclusive, at least until we get to some kind of proportional representation within our media (and then we should probably go way over that line for the next few thousand years or so, to balance the ledger).

I want to play more games like Return of the Obra Dinn - games that acknowledge their place within a context, historical or otherwise, games that explore themes as opposed to regurgitating them, games that leave some things unsaid, games that are brave enough to say something in the first place, games that can be criticised as thoughtful expression. (If you have particular suggestions for me, just let me know!)

In the meantime, I’m really happy that it exists, and I’d love for more people to play it and/or write about it! I’ve only covered a few of the elements that really captured or excited me - to get a much more thorough take on the game, Laura Hudson’s recent essay is a fantastic place to start.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like