Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Why do games appeal to gamers? Is there another way to look at the issue than as a taxonomy of player types? In this article, researcher and writer Jason Tocci investigates and categorizes different types of game appeal.

April 19, 2012

Author: by Jason Tocci

I once happened upon my brothers attempting to fly an SUV off a cliff. This was years ago, when Grand Theft Auto III was still new, but it was already easy enough to search online for the cheat code to make cars fly. After about an hour of trying to glide across a river and into a football stadium, they finally cleared the edge of the wall, landed the car inside, and broke into proud laughter upon discovering the Easter egg inside: an image of fans spelling out the name of Liberty City's football team: "COCKS".

I often think back on this when I read various theories on why we find games "fun." Some of the most popular theories of engagement come down to offering an optimal level of challenge, establishing a pleasant "flow" state. Surely there was something like that going on here, but there was also so much more, from the thrill of intentionally messing with the laws of physics to the naughty humor in the final payoff.

Theories that account for a range of different types of players, meanwhile, have been useful in considering that games affect us on more levels than simply how challenging they are.

In the process of trying to simplify and codify how people think, however, these theories have trouble accounting for how a game can affect a person in different ways and in different contexts, or how to address appeals of games that don't fit quite as neatly into a carefully-structured model.

In this article, then, I offer five general categories of appeal (hence, "appeals") describing a host of different -- but not necessarily mutually exclusive -- ways that we engage with games.

This framework of appeals has been developed through research conducted between 2008 and 2011, including discourse analysis of online sources (e.g., collecting examples from public forum discussions and blog comments; see "'You are dead. Continue?'") and participant-observation ethnographic research (e.g., playing games with people in arcades; see "Arcadian Rhythms").

The appeals I'll offer aren't necessarily all "good" appeals -- this framework includes ways that games engage players that some designers have criticized as little more than manipulation -- but they may offer some broad ways to describe what makes games tick, and how to blend different kinds of appeals to encourage or even discourage different kinds of engagement.

I describe this theory quite purposely in terms of the characteristics of games and play instead of the characteristics of players themselves. Models of player personality and demographics are very attractive in their elegant simplicity, whether you're talking about the common-knowledge distinction between "casual" and "hardcore" or more scientific approaches drawing on social psychology. (See Bart Stewart's relatively recent Gamasutra feature for one such robust approach.)

Nevertheless, it may be more productive to describe engagement with games according to a variety of approaches to play itself, for at least three major reasons.

First, theories of "player types" often don't easily match up with empirical and anecdotal evidence of how people actually play games. We can display different "personalities" between different games, or even within a single game that offers a variety of different mechanics.

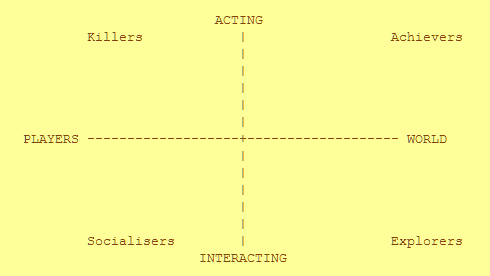

Take, for instance, the anecdote that began this article, in which my brothers continually flew a car off a cliff. What type of players are my brothers in this example -- say, in terms of Bartle's types?

Are they explorers, fiddling with the game systems and investigating its world? A large part of the reason they were attempting to get into that stadium was indeed that they wanted to know whether the game logic would allow them, and they wanted to discover whatever might be inside.

Are they achievers, looking to beat a rules-based challenge? It was a challenge of their own making, but they still had a distinct end condition, and even a sort of in-game reward in the Easter egg.

Are they socializers, playing side by side, telling a story together through their play? Certainly, playing cooperatively and sharing a laugh had something to do with the appeal.

Are they killers, going out of their way to subvert the rules of the game? They couldn't have played this way at all if it weren't for the fact that they entered a cheat code.

Does it change our answer if we find out that they also played the game separately from one another on other occasions, each following the rules and paying attention to the plot? Or does it change our answer if we find out that they approach other games completely differently -- say, eschewing any "cheating" or exploration in competitive sports games?

To be fair, Bartle originally suggested this typology not to describe all game players, but to describe MUD players. He even makes the point that three kinds of players aren't treating the MUD as a "game" at all, but as "pastime," "sport," and "entertainment," and acknowledges that "most players leaned at least a little to all four [types], but tended to have some particular overall preference."

The fact that game critics and designers have applied this typology more broadly may reflect an admirably progressive willingness to broaden our understanding of what a "game" can be, but it also extends this particular model well beyond the claims of the original 30-person study that brought it about.

My goal with this thought exercise, then, is to illustrate the problem with focusing on a small group of players or a single genre. Players exhibit different preferences and behaviors with different games or in different social contexts, which makes it problematic to claim that anything so fixed as personality or an inherent "type" is at the root of enjoyment. My brothers played the way they did not just because of who they were, but because of the context of the situation: Each was sharing the game with another player he knew very well, and they were playing a game whose design allowed them to play it in multiple ways.

This brings me to the second major issue with describing how we engage with games based on types of players instead of types of behaviors. By suggesting that we design games around categories of players, we run the risk of reifying our own top-down notions of what the player base is like.

This risk could be as innocuous as simply missing out on audiences that we didn't know existed -- a segment of players that requires more nuance to understand than "hardcore" or "casual," perhaps, or that can't be defined as any of killers, achievers, explorers, or socializers. More problematic, however, designing games with player typologies in mind opens the doorway to reinforce stereotypes of which games different people "should" be playing, and which play styles are more valid than others.

In his original article, Bartle didn't have much good to say about the "killers"; they were basically the Slytherin of player types, a category for those who don't play well with others. Bart Stewart's Unified Model goes some way toward legitimizing their activities as a valid play style that most games simply aren't designed to accommodate, but the fact remains that the original typology was constructed in such a way that essentially demonizes a segment of players. In the meantime, releases like Gears of War have demonstrated that there's a market for games that explicitly encourage "killer" play styles, such as by offering brutal and demoralizing ways to dispatch with opponents.

Even more problematic than missing out on audiences, however, is to unintentionally exclude audiences by assuming that certain games are only for certain "types" of players. This risk is probably less in overt categorizations than in implicit or easily inferred connections, like the common assumption that women are more likely to be "casual" gamers, and less interested in games like fast-paced, first person shooters.

To be fair, some studies have indeed observed different preferences between different demographics, and some have even attempted to explain such differences -- say, in terms of innate, cognitive differences between men and women (e.g., see John Sherry's "Flow and Media Enjoyment" [pdf link]). Again, however, it's important to consider the huge role that context can play in terms of what people will feel comfortable engaging in -- or, to put it another way, what they'll even bother to try.

Consider a study by Diane Carr, for instance, which found that when girls were given the chance to regularly play whatever games they wanted in a comfortable, non-judgmental atmosphere, expectations from both stereotypes and other empirical evidence practically disappeared. Yes, men might have a slight neuropsychological edge at navigating a 3D maze in a first person shooter, but that's probably not what's keeping more women from playing. The fact that a game is popularly considered more "meant for" some audiences than others is worth considering as a factor in who chooses to play, rather than who would be capable of enjoying it.

From the standpoint of simply designing more engaging games, however, the greatest reason I see for thinking in terms of "game appeals" is that it's a lot easier to contemplate how to blend different appeals than different personalities. Through design, we can make room for a number of different ways to enjoy a game, or we can purposefully pare down the number of appeals a game offers so that they don't conflict with one another in unintentional ways. Before I offer some more specific examples of how to think about this, however, I'd like to suggest what I see as some useful categories to think about appeals.

Researchers, critics, and designers have suggested a lot of ways to analyze the ways that games can engage players. Why throw in one more? Partly, I offer this approach to validate some excellent ideas suggested by others, backed up with additional research. In addition, however, I offer this approach to fill some gaps that may not be discussed on a widespread level yet. And finally, so much of the research and theory on how we engage with games either focuses very specifically on challenge, or defines engagement with games in terms of "fun".

Given that recent years have seen an explosion in popular games that are not at all challenging, and a quieter expansion in "serious" games that provoke thought more than provide amusement, it seems a good time to draw attention to broader concepts of how we play.

I do, of course, intend to follow the grand academic tradition of borrowing wholeheartedly from my favorite theories. Bart Stewart's Unified Model is especially useful in recognizing that certain player behaviors represent legitimate styles of play that designs can purposely accommodate; "griefing" isn't necessarily just for jerks, but something that can be built into a game to appeal to certain needs and interests.

Mitch Krpata's New Taxonomy of Gamers offers some usefully fine-tuned distinctions between different kinds of challenge, immersion, and recreation. Michael Abbott's Fun Factor Catalog offers a data-based set of appeals, but without much rigorous, systematic organization to date (as it is still a work in progress).

Hunicke, LeBlanc, and Zubek's MDA [pdf link] (Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics) approach, meanwhile, offers perhaps the most comprehensive range of ways that players engage with games, but leaves some aspects relatively unexplored. Few theoretical approaches even recognize "submission" as a reason people play games -- so what does it look like?

Consider here, then, five categories of game appeals:

Accomplishment: Appeals involving extrinsic and intrinsic rewards.

Imagination: Appeals involving pretending and storytelling.

Socialization: Appeals involving friendly social interaction.

Recreation: Appeals for adjusting physical, mental, or emotional state.

Subversion: Appeals involving breaking social or technical rules.

Though my own research has focused primarily on video games, I've noticed that many of these appeals may be equally effectively applied to analysis of how other sorts of games are designed, as well. I'll suggest a few specific appeals for each category, but there is likely room for more.

Accomplishment refers to the rewarding feelings that come from "winning" or otherwise succeeding at a game. Related appeals include completion (finishing a game, getting all the trophies/achievements/unlockable content), perfection (improving one's skills at the game), domination (besting other players), fortune (earning a reward through chance), and construction (using a game to create art or objects).

I take a cue from Mitch Krpata here in making a distinction between completion and perfection. As I found in my own research, completion is what inspires players to earn every Achievement in Halo 3, but perfection is what inspires them to achieve the highest multiplayer ranking possible. Domination is also a factor in the latter, but a player can find satisfaction in defeating other players even if she isn't necessarily improving her skills (as even expert players sometimes take pleasure in crushing poorly matched opponents).

Note, however, that accomplishment doesn't necessarily only include mastering a game through one's own skill, but simply winning at it. Players still find something appealing in lining up three cherries on a casino slot machine, or harvesting all their crops on time in FarmVille, even if there was no actual skill involved in the "win". This is why I add an additional appeal for fortune, representing a sense of accomplishment through no actual ability, or perhaps even any effort.

After describing all of these appeals, it may seem odd to group construction -- an expressive act -- alongside more traditional concepts of "winning." I include this here, however, because acts of creativity in games are similarly goal-oriented, and often accompanied by external indicators of success or failure (such as appreciative comments by forum-goers looking upon your screen shots).

Whether the end result is a mosaic of the Mona Lisa rendered in FarmVille crops, an especially attractive Skyrim character, or an exquisitely-constructed palace in Minecraft, construction offers a sense of user-definable accomplishment all its own; what the game contributes is a platform that makes this possible.

Imagination refers to practices of pretend, with particular regard to storytelling and simulation. Related appeals include spectatorship ("watching" stories), directorship ("making" stories), roleplaying (pretending to take on another kind of identity), and exploration (pretending to exist within a pretend landscape).

Different games emphasize different imagination appeals to varying extents. Skyrim, for instance, has a heavy emphasis on directorship and exploration. Go on any Skyrim forum online, and you'll find plenty of players sharing detailed stories of their adventures and the unexpected things they encountered, each different from the others. There's room for roleplaying -- many players generate quite a bit of back story and additional context for their characters -- but the game itself doesn't really ask players to do this, at least not directly.

In contrast, Mass Effect offers less in the way of exploration, giving players a more linear path to explore, but it more directly guides roleplaying and focuses more on spectatorship, with cinematic cutscenes and clearly defined personality options for the protagonist. Players still have a sense of directorship, discussing on their own forums how they made different choices and told different stories, but the range of narratives is narrower because the game is written to more resemble Hollywood storytelling techniques. Gears of War, meanwhile, offers no opportunity for directorship in its campaign mode, but through dialog, cutscenes, and music, still offers opportunities for spectatorship.

I also humbly posit that spectatorship should include not just engaging with the story of a game you're playing, but engaging with the story of a game you're watching someone else play. This refers not only to players I've spoken with in the course of my research who make their spouses buy certain games so they can watch somebody else play through for the story, but also to the many thousands of spectators of professional sports at stadiums and in front of televisions. Though "winning" plays a part in people's enjoyment of such games, the unfolding drama of a game in progress, with an uncertain end, can appeal to both players and spectators alike.

Socialization refers to the various ways that players use games to connect with one another on an interpersonal level. Related appeals include conversation (through game chat during play, or made possible through in-game messaging), cooperation (supporting and helping one another during play), and generosity (helpful behavior in a more one-way direction, like giving gifts or helping a low-level player advance more quickly).

You could, of course, argue that socialization is an appeal of any entertainment medium, from discussing favorite books with a friend to attending a movie in a crowd. Games, however, can be (and often are) specifically designed to encourage particular kinds of socialization over others.

Rock Band, for instance, is fun in groups not just because multiple people can play at the same time, but because it actively fosters a sense of cooperation: Players rely on one another and can help each other. If one player does poorly, the song could end for everyone, so other players must be mindful about when to save floundering teammates by triggering "Overdrive" mode.

Many team-based action games also rely on conversation between teammates not just to chat about how your day went (though players use games as a social gathering for just that purpose), but also to share tactical information and plan group actions against opponents.

Less formally explored, however, are more one-way generosity mechanics -- helping out players without necessarily receiving a reward for oneself. That may sound like it would be a contradiction in terms: Once you design a system that recognizes one player helping another, doesn't that necessarily imply a reward for the charitable player, making this more appropriately described as cooperation? I'd argue that this isn't always the case, but such a system may have yet to be designed in a truly satisfying way.

FarmVille, for instance, does allow for cooperation-free generosity by giving players the option to send one another gifts at no cost. One could ask for reciprocity (and players often do), but some players happily use this feature simply because they enjoy giving gifts to others.

Unfortunately, the system is designed better as a marketing tool than as an appeal because the result is often unwanted Facebook messages notifying players' friends that they have a "gift" waiting in a game they don't play. Some MMORPGs also offer formalized "mentor systems" (see Shadow Cities or Final Fantasy XI), suggesting that there is room to actually design for such appeals, though this is more typically arranged by players through less formalized means.

Recreation refers to processes of renewal and pastime, which typically means using a game to adjust one's psychological or psychological state. Related appeals include mood-management (toward relaxation, elation, amusement, or other emotions), distraction (actively avoiding thinking of painful or difficult stimuli), contemplation (pondering thought-provoking issues), and exertion (getting physically energized through play).

The broadest of these appeals is mood-management. I offer this as a single appeal, rather than offering each type of mood-management as its own appeal (relaxation, amusement, excitement, etc.), not only because that list would quickly get unreasonably long, but to make a distinction between appeals as play-behaviors and emotional states as their end result.

That said, it's worth making note that mood-management encompasses a great many more states than "having fun." flOw, a slow-moving, soothing game, was specifically designed to show how games might encourage relaxation rather than elation. Shadow of the Colossus and Final Fantasy VII have received praise for sometimes effectively encouraging sadness over happiness. Players choose different games based on context, depending on their company and their preferred mood.

Contemplation is a related appeal, perhaps even part of mood management. Passage, for instance, is a short game with subtle implications rather than an obvious goal for "fun." It's a game that is calculated to make you think, rather than to make you enjoy yourself. Distraction is another related appeal, and one that may not sound very worthwhile, given that it can be taken to refer to shutting out other responsibilities that need to be dealt with (as with compulsive gambling, for instance). Even so, distraction is at the heart of why games make such excellent therapeutic tools in hospitals, effectively acting as non-medicating pain-reducers.

One of the main reasons I think it's important to give recreation its own category is that it includes the main appeals that have skyrocketed many so-called "casual" games to success, from Facebook and mobile "social games" to motion-control games on the Wii and other systems. Regardless of whether critics or designers find their tactics to be nothing more than extortion, the success of skill-free games like FarmVille and Tiny Tower should suggest that these games are giving players something that they want.

Rather than lamenting that players are unfortunate dupes, it's worth considering that maybe players are getting precisely what they want from these games, at a price players are willing to pay. And while many traditional gamers lament that Wii "shovelware" games do little to scratch the surface of what motion control technologies could do, it has done little to slow sales of the system. Even the least thoughtfully-designed Wii game might offer some opportunity for pleasant physical exertion in the hands of someone eager to cut loose in the living room.

Subversion refers to behaviors that run counter to norms and expectations, as defined by society and game logic alike. Related appeals include provocation (actively antagonizing other players through "inappropriate" behavior), disruption (breaking game logic and exploiting glitches), and transgression ("playing evil", such as killing friendly NPCs).

I group these appeals because each involves breaking some kind of rule. Provocation involves breaking implicitly agreed-upon social norms about how people are expected to act in games and in polite interaction. Disruption involves breaking rules hard-coded into the game -- and, if you use those rules to your advantage in a multiplayer game, breaking the aforementioned social contract of "fair" play.

Transgression is generally considered the least offensive of these, as the rules broken are broader cultural norms, and generally permitted by fellow players and game rules. Nevertheless, I group this sort of transgression along with the other subversion appeals because the root of enjoyment behind this activity is, as more than one person said in the course of my research, "being a dick". The basic appeal of each of these activities revolves around doing something you know you're not supposed to be doing.

I give these attention as valid appeals, rather than dismissing them as griefing, glitching, and cheating, simply because so many players enjoy doing this sort of thing that it may be helpful to avoid thinking of it as a deviant behavior. (For a comprehensive account, see Mia Consalvo's book, Cheating.) How can designers account for this appeal?

The most obvious answer, of course, is that actually accounting for subversion neuters it entirely. How can you encourage rule-breaking and also leave the thrill of breaking the rules? That doesn't necessarily tell the whole story, however. Designing a path for "evil" play is one way to offer a transgression appeal: In Fallout 3, for instance, the player breaks no game-logic rules by sharing a friendly meal with cannibalistic murderers or by selling a small child into slavery, but still gets to enjoy bucking traditional narrative expectations and social norms.

Designers can even formalize provocation in a game where copping an attitude might be an expectation of the community: The aforementioned player-on-player brutality of Gears of War (with the option to punch an opponent's face for several seconds even after you've beaten them) might arguably be called a formalized approach to griefing. These offer ways to break the rules of normal social conduct without breaking the rules of the game.

Admittedly, it's trickier to suggest ways to encourage players to actually break the game rules without running the risk of actually destroying the game (or at least crashing multiplayer servers). Cheat codes and Easter eggs offer a sort of sanctioned subversion -- breaking game rules on a controllable scale.

Could we imagine a game that even more purposely encourages this sort of appeal -- say, a Matrix-style science-fiction game where glitching actually makes sense in the context of the game world, and interesting glitches get formalized as part of the game rules? I certainly wouldn't want to be the one in charge of making sure the game doesn't fall apart as players scramble to find ways to do just that, but it would be interesting to see some developer try something like it. For now, subversion may represent the most unexplored category of appeals to date.

Reading over these appeals, you may notice that they aren't at all mutually exclusive -- and, in fact, that's entirely the point. This allows us to discuss the many ways in which they intersect for good and ill, and how to design games to capitalize on these intersections.

Finding and exploiting a game's glitches, for instance, offers subversion-related appeals in breaking the rules, but it may also offer accomplishment-related appeals in giving oneself an edge against opponents, or even just in uncovering the secrets of the game system. Playing Dance Dance Revolution offers accomplishment-related appeals in achieving a high score on difficult songs, socialization appeals in dancing alongside other players, and recreation appeals through physical exertion.

Different game appeals sometimes map to different game mechanics, but they don't have to. A game can offer imagination appeals entirely separately from accomplishment appeals by having narrative cutscenes that feel completely irrelevant to player input, but it could also blend imagination and accomplishment by making dialog interactive, even challenging.

Dialog scenes in Mass Effect 2, for instance, offer an appeal of directorship by allowing the player to choose how to respond, but there's not much room for a the appeal of perfecting one's skills; some responses yield objectively better results than others, but the best responses are clearly color-coded, and generally achievable so long as you choose consistently "good-guy" or consistently "bad-guy" responses.

In contrast, dialog scenes in games like L.A. Noire and Deus Ex: Human Revolution add an additional layer of challenge by requiring the player to gauge characters' facial expressions and body language in choosing the most effective responses.

No less important than blending appeals, of course, is anticipating how different appeals might conflict with one another. This offers designers an opportunity to prioritize features, or offer additional context for features, based on the appeals they most want to encourage. As I described in an article in Eludamos, for instance, "dying" in a game is usually hugely disruptive to storytelling, but it's typically considered an appropriate way to make players feel they have something at stake in failure.

In other words, it's a traditionally-accepted concession to accomplishment appeals at the cost of imagination appeals. Some games do, however, anticipate this conflict and attempt to compensate for it, such as by explaining away death through narrative means -- reviving as a clone in BioShock, or finding out that the death was a mistake by an unreliable narrator in Prince of Persia: Sands of Time.

A more dramatic approach is to completely exclude certain features to ensure that the appeals you most want to encourage are most salient. Consider, for example, how game designers might deal with the potential conflict between imagination appeals and socialization appeals. A cooperative, multiplayer campaign like in Borderlands or Gears of War offers opportunities for socialization with friends, and may even help make challenges more manageable -- but these appeals may come at the cost of imagination if your friends have a tendency to chat over cutscenes.

Demon's Souls also features cooperative and competitive multiplayer mechanics, but it prioritizes imagination appeals (like being drawn into a tense atmosphere) over socialization appeals (like chatting with friends). You can't communicate directly with other players through voice chat, but only interact with them as ephemeral ghosts or indirectly, by leaving brief messages written on the ground. By forcibly isolating players in their own dangerous worlds, the result is arguably much more thematically and stylistically consistent than it could have been with a voice chat function.

While it won't always be obvious which appeals are likely to conflict and why, describing game features according to this approach does at least offer a means to critique what has worked and what hasn't worked in existing games. And by considering all of these appeals on even standing, it's my hope that we might see more games that experiment with prioritizing some of the least widely utilized appeals, for the sake of innovation, exploration, and -- if I may be permitted to say so -- fun.

This theory of game appeals represents an attempt to cover a lot of ground. That said, I see this not as an all-encompassing, universal taxonomy, but as a starting point for a way of thinking about games that sees potential value in a broader range of design approaches.

Moreover, I also see plenty of room for additional appeals, or for taxonomical reshuffling as further research recommends. Do skill-free "social games" have more complex workings than I give them credit for by only describing their appeals in terms of recreation and chance accomplishment? Do motion-controlled games like those on the Wii and the Kinect -- or athletic sports, for that matter -- deserve an entire category separate from recreation, breaking kinesthetic activity into more varied and nuanced appeals? I would have loved to have investigated such questions myself more fully, but I'm hoping others will suggest how to fill in the gaps.

Beyond being a mere theoretical exercise, however, I also hope that these discussions can lead us to designing an even broader variety of thoughtful and innovative games. When designers and developers define games as obstacle courses whose primary purpose is to elicit "fun," we miss out on other kinds of engagement and experience. And when we describe players as if they could be so easily fit into a small handful of categories themselves, not only do we forget that we can intrigue and delight one player on multiple levels, but we run the risk of never reaching the players -- or creating the genres -- that we have yet to discover.

Michael Abbott (2010). "Fun factor catalog." Brainy Gamer. http://www.brainygamer.com/the_brainy_gamer/2010/08/fun-factors-catalog.html

Richard Bartle (1996). "Hearts, clubs, diamonds, spades: Players who suit MUDs." http://www.mud.co.uk/richard/hcds.htm

Robin Carr (2005). "Contexts, gaming pleasures, and gendered preferences." Simulation and Gaming vol. 36, iss. 4, pp. 464-482. http://sag.sagepub.com/content/36/4/464.short

Mia Consalvo (2007). Cheating: Gaining advantage in videogames. MIT Press. http://mitpress.mit.edu/catalog/item/default.asp?tid=11153&ttype=2

Robin Hunicke, Marc LeBlanc, and Rober Zubek (2004). "MDA: A formal approach to game design and game research." In Proceedings of the Challenges in Game AI Workshop, 19th National Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI '04, San Jose, CA), AAAI Press. http://www.cs.northwestern.edu/~hunicke/MDA.pdf

Mitch Krpata (2008). "A new taxonomy of gamers." Insult Swordfighting. http://insultswordfighting.blogspot.com/2008/01/new-taxonomy-of-gamers-table-of.html

John Sherry (2004). "Flow and media enjoyment." Communication Theory vol. 14, iss. 4, pp. 328-347. http://icagames.comm.msu.edu/flow.pdf

Bart Stewart (2011). "Personality and play styles: A unified model." Gamasutra. http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/6474/personality_and_play_styles_a_.php?print=1

Jason Tocci (2010). "Arcadian rhythms: gaming and interaction in social space." Reconstruction vol. 10, iss. 2. http://reconstruction.eserver.org/102/recon_102_tocci01.shtml

Jason Tocci (2008). "'You are dead. Continue?': Conflicts and complements in game rules and fiction." Eludamos vol. 2, iss. 2. http://www.eludamos.org/index.php/eludamos/article/view/43/81

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like