Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Atari Games, in its heyday, produced some of the most brilliant game designs the world has ever seen - from Marble Madness to Tempest and beyond - and Gamasutra compiles the 20 essentials throughout the company's long arcade career.

As far as the [arcade] industry itself goes it had become -- and still is -- severely polarized. The only titles that were succeeding were SSJPK fighting games -- Side-Scrolling, Jump-Punch-Kick -- a very few sports titles, and high-tech driving titles. The market had become completely indifferent to innovation in game design.

It seemed that all our management wanted to see in development was whatever was currently earning money. For so many years Atari had led the industry in innovation by constantly looking forward. Now we weren't even looking over our shoulders, we were struggling to climb on a tired bandwagon.

-- Ed Rotberg, speaking around 1996, in James Hague's book Halcyon Days: Interviews with Classic Computer and Video Game Programmers

What happened to the Atari fanboys? Nintendo and Sega have theirs, Blizzard and Bungie too, Square and Enix, Capcom and SNK. Yet Atari Games, in its heyday, produced some of the most brilliant arcade game designs the world has ever seen. Unique and idiosyncratic, at its best it made games the likes of which no one else could. Later, it is sad to say, it produced games that no one else would want to.

Some people rave about Nintendo; how its designers come up with new ideas so often, about its fearlessness in taking risks with unconventional designs, and how it reinvents its franchises endlessly.

But even Nintendo has never been as original, as brilliant, as determined to design what developers think best regardless of what management, critics, and eventually, even players might have to say, as was Atari Games in its heyday. A trip through Atari's classic arcade game catalog is like a course in game design all by itself.

Arguably, this was the company that kept the spirit of classic arcades alive the longest -- as late as the early '90s. Even now, the company-which-calls-itself-Atari -- which should not be confused with the company this article is devoted to -- shills out the memory of the former arcade powerhouse with GBA and DS ports of classic-era games.

Many of Atari's games were the targets of unequaled numbers of home adaptations. Rampart has over a dozen, and no one knows how many versions of Breakout are out there, considering how shareware authors have adopted and colonized the idea -- not to mention Taito, and Arkanoid.

Atari, particularly the arcade division that split off from the company in the '80s rechristened "Atari Games," seemed restless with ideas. A game where players race marbles through a world of grid lines? Float innertubes down fantastic rivers? Defend castles with walls and cannons? Skateboard while chased by bees? Deliver newspapers?

While the company also had its share of less-than-memorable ideas (Pit-Fighter, Thunderjaws, Batman, most games after 1991), it is easy to overlook such missteps when the company also gave us Tempest. And at its best, Atari Games seemed almost embarrassingly creative.

Other companies could deliver with the absurd premise once in a while (what the hell was Namco smoking when it released Phozon?), but Atari used to do it all the time. At least, Atari didn't stop doing it in 1986. It released an update of Breakout the same year Capcom started selling Street Fighter II. I consider this to be unspeakably awesome, but it should be understood that most players at the time would have disagreed with me.

Highly ingenious core play mechanics. These tend to be clever and unique, even while other arcade games were starting to become genrefied. Atari did release some genre titles, Pit Fighter in particular, but until 1992 the company never seemed to be quite comfortable with it. Most of those games are relatively obscure today, although Area 51 has shown itself to have legs.

An emphasis on procedural content as opposed to hard content. Atari was more likely to give the player algorithmically modified, changeable levels than hard-coded sequences. Gauntlet gives players different levels from a pre-made set every game, and manipulates food power-ups depending on game difficulty, average score per coin, and number of players.

While it always goes through the same general areas, Toobin's level order and layout can be quite different depending on which forks are taken. Skull & Crossbones shortens levels on easier difficulties. Atari Tetris uses the high score initials as preset blocks late in the game.

Level warps for skilled players. Many games feature these. Sometimes these are offered as a choice at the start of the game, like the wave selectors in Tempest and Star Wars or the score selector in Millipede, but some games would build the warps into the game itself, or even hide them.

Crystal Castles' warps are hidden places in certain levels. 720 Degrees and Rampart have a simple novice/advanced selection. Klax has two kinds of warps: the basic selection kind which appears often in the game, and "secret warps" which are activated by performing a special trick. S.T.U.N. Runner has secret routes in its levels that lead to warps. Gauntlet and Gauntlet II have them, Toobin' has them, even Tetris has them -- they are everywhere.

Distinctive sound. The venerable POKEY I/O and sound chip was used by Atari for much of its history. Used in arcade systems and 8-bit computers alike, like MOS/Commodore's SID chip it has a characteristic sound sought after by chiptune musicians.

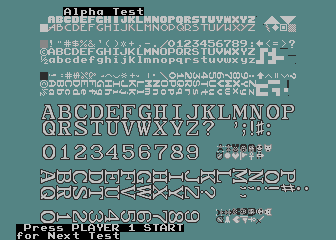

The Atari font. This all-capital, 16x16 pixel, monospace serif font began seeing use around the time of Marble Madness, where it's used for the timer and high score entry letters, and appeared in many Atari games from then on. Since Atari Games differ so much from each other it helped to give the company's output a distinctive look.

The Atari font. This all-capital, 16x16 pixel, monospace serif font began seeing use around the time of Marble Madness, where it's used for the timer and high score entry letters, and appeared in many Atari games from then on. Since Atari Games differ so much from each other it helped to give the company's output a distinctive look.

It makes appearances in games as late as Gauntlet Legends (1998) and Dark Legacy (2001). It was pervasive enough that, even if the game contains no visible use of the font, if one were to go into the operator settings of a 1984-1991 Atari arcade machine and page through them, one would invariably run into the font after a few button presses.

The Atari Bell. Used nearly universally, for a while, as a credit insertion notification, again starting around the time of Marble Madness. It is not identical between games; Marble Madness uses a different bell than Gauntlet.

Per-credit scoring. For games that allow unlimited continues and that don't reset score after a continuation, it is strange, but Atari Games is the only major game developer to make frequent use per-credit score tables. By this time arcade games had already begun moving towards play-to-win instead of play-for-score, but for games that care about score this is a great concept.

Before we begin, I need to more clearly define what I mean, exactly, by "Atari." The company's name is a term from Go; when a group of stones is one move away from being captured, they are said to be in "atari."

Founded as "Atari Inc.", the company was famously created by Nolan Bushnell to produce Pong machines in the early '70s, and there was no ambiguousness in the use of its name until Jack Tramiel bought the company off of Warner Communications after the great game crash of 1983, when mainstream tastes suddenly shifted away from the video game fad.

Tramiel, fresh after helming Commodore's success with the Commodore 64 home computer and seeking a repeat, bought only Atari's consumer electronics division from Warner. While Tramiel's "Atari Corp." did okay for a while, giving us the Atari 8-bit computers, the Atari ST, and the Jaguar, it didn't last as long as the arcade company -- Atari Games.

It's worth noting now that this article is not interested in the Tramiel Atari, the consumer products of the old Atari, Inc., nor will it cover Atari Games' home publishing efforts, either under the name Tengen or their own. We're interested solely in arcade games.

Atari Games' ownership changed hands frequently at that time, but that didn't prevent it from experiencing a great creative flowering. This is the era that gave us Marble Madness, Gauntlet, 720 Degrees, Atari's version of Tetris, Klax, Toobin', Vindicators, Xybots, Hard Drivin', S.T.U.N. Runner and many other unique games. Eventually Atari Games was sold to former competitor WMS, a.k.a. Williams Electronics, who also owned former competitor Midway.

The company's creative ascendancy seems to have ended around 1992. According to developer interviews from the various console compilations that have been released, Atari's developers had been continually stymied by the difficulty in coming up with original arcade ideas that tested well against fighting games, causing many projects to be abandoned.

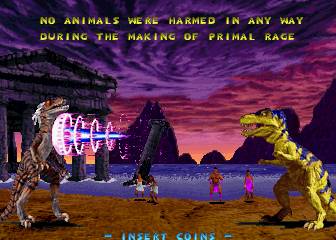

One of the abandoned games was the sequel to Marble Madness, Marble Man. Little other than fighting games and racers tested well. Atari Games even tried making a couple of fighters of its own, with the most famous example being the moderately successful dinosaur fighter Primal Rage.

One of the abandoned games was the sequel to Marble Madness, Marble Man. Little other than fighting games and racers tested well. Atari Games even tried making a couple of fighters of its own, with the most famous example being the moderately successful dinosaur fighter Primal Rage.

Some of the company's late successes include the Area 51/Maximum Force series of light gun games, the San Francisco Rush series of "exploratory" racing games, and Gauntlet sequels Legends and Dark Legacy.

By the time of Gauntlet Dark Legacy, the company had been renamed Midway Games West, and had found some work on the home adaptations of some of its arcade hits, but the continued implosion of U.S. arcades doomed the studio. Midway left arcades in 2001, and disbanded the studio formerly known as Atari Games in 2003. These days, the name "Atari" is used only by Infogrames.

Sprint (series)

1974-1989

Designed by Dennis Koble, Robert Weatherby, Kelly Turner, maybe others

When we talk about classic arcade games, it is amazing that we tend to forget about an entire era of arcade history. Video gaming did not jump instantly from Pong in 1972 to Space Invaders in 1978. There were many games in the intervening years, although only Breakout is really remembered today -- mostly due to its Atari VCS ports.

Many other early Atari 2600 games were arcade adaptations, renamed for the system: Combat (formerly Kee Games' Tank), Air/Sea Battle/Target Fun (Anti-Aircraft in arcades), and the many Pong-likes which made it into Video Olympics. The Sprint games, the basis of Indy 500 on the VCS, are especially notable.

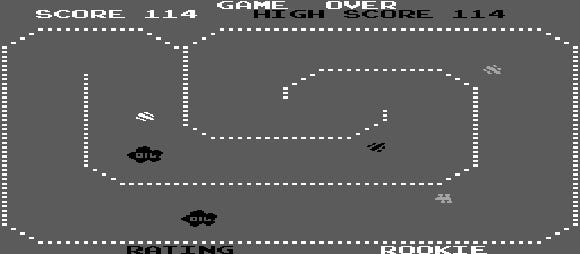

I call the series Sprint, but the original game was named Gran Trak 10. Atari released no fewer than ten versions of what amounts to the same game over their history: Gran Trak 10, Gran Trak 20, Le Mans, Sprint 2, Sprint 4, Sprint 8 and Sprint 1 were all pre-classic arcade games.

Some were released under the name Kee Games, a shell company Atari created to get around distributor restrictions. Amazingly, Atari Games would return to the series in the late '80s with Super Sprint and Championship Sprint (both 1986), and Badlands (1989).

While the updates add 16-bit graphics, vehicle upgrades and, in the case of Badlands, weapons, they still amount to the same game: a race game with single-screen tracks and tiny vehicles, steered with a steering wheel controller and a gas pedal. Take a moment to let the awesomeness of that fact sink in.

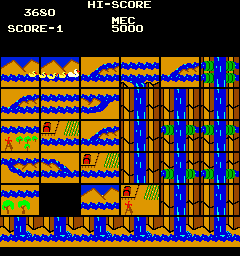

Sprint 1

Sprint 1

More awesome yet, even the original games, released a mere two years after Pong, are quite playable today. Since then, driving games have picked up a third dimension, cockpit and behind-the-car perspectives, sprawling tracks, drift mechanics, realistic damage, tremendously varied vehicles, weapons, navigation tasks, simulated worlds to drive through, and a slew of other features. But at their core, they all seek to duplicate what Gran Trak 10 did in 1974.

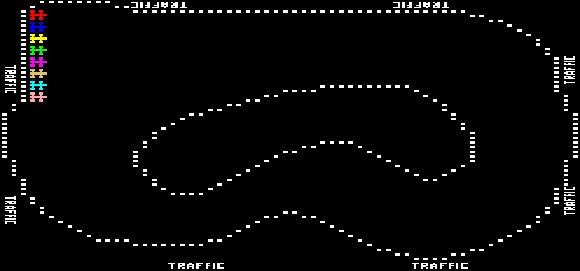

Sprint 8

And one of Sprint's features has yet to be equaled: Sprint 8 was a driving game played by up to eight players, around a gigantic monitor table in the middle, two to a side, all with their own steering wheels and gas pedals. No, wait; it was equaled once: by Kee Games' Tank 8.

And it wasn't just Atari that followed this successful formula: Midway's Super Off-Road is nothing more than a slower Sprint with bigger tires, turbo boosts, upgrades and multi-level tracks.

While it doesn't seem like it would be that kind of game, Championship Sprint has an end. I've never seen it myself, for it's one of those games that's fun to play for just a few minutes at a time, but that doesn't really lend itself to long sessions. While Badlands was released in 1989, the game was always a creature of its pre-Space Invaders design ideals.

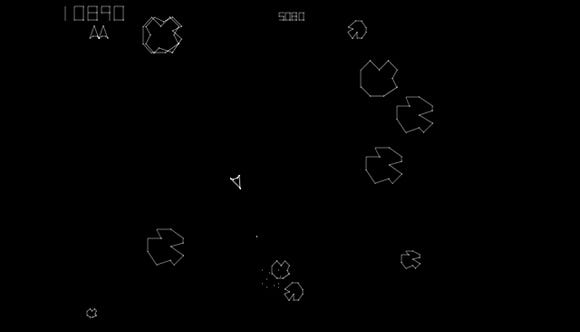

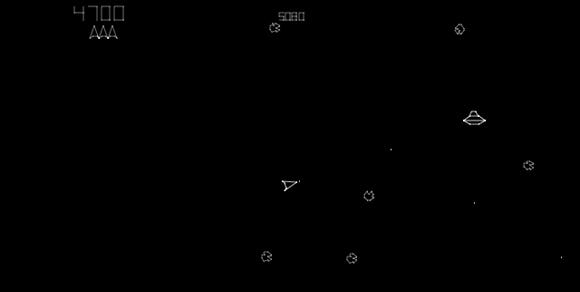

Asteroids

1979

Designed by Lyle Rains and Ed Logg

Taito's Space Invaders came out in 1978, and changed video games forever. Earlier games would give the player a limited amount of time to rack up points, but Space Invaders, borrowing a concept from pinball, gave the player a limited number of lives, and even the opportunity to earn an extra. So pervasive was the idea that, even now, it is everywhere.

Asteroids came out the year after Space Invaders, and it took its ideas and ran with them. Space Invaders awards one extra life throughout the entire game, but Asteroids awards repeatedly as the player continues to earn points. This makes it the first "game of attrition," where it's expected the player will continually lose lives, so the game continues to award them.

This turns out to be a big mistake in Asteroids, since there exists a good strategy, the infamous "hunting" technique, that can take players to very high scores with little risk. But that idea, of attrition, was influential too: Defender, out the year after Asteroids, relies heavily upon it.

Asteroids is also notable for being what amounts to a rudimentary physics game. That is, a game that ultimately derives its play from simulating Newtonian motion. The player's ship, the rocks, even shots all have mass and inertia. When shooting, the ship's velocity is added to that of the shots coming out of the ship. Many things that are considered physics games now have to do with masses interrelating, colliding or connected with springs, but this is 1979 we're talking about.

One of the core ideas of Asteroids, which is now ubiquitous but was rather daring at the time, is the idea that the ship's movement is relative to its orientation and not the player's. Pressing the "turn left" button doesn't cause it to face the left side of the screen, but to rotate to its left.

The thrust button doesn't cause the ship to move up the screen but in the direction it's facing. While the player's not inside the vehicle being controlled, just like controlling an R.C. car, movement isn't direct but indirect.

It is not overstating things to note that this idea has since saturated gaming. Many 2D games could do without it, but when 3D came along it became indispensable. Tomb Raider, for example, makes heavy use of it. Many say Resident Evil was crippled by it.

Once you grant the camera the ability to change angle independently of the protagonist, it becomes harder to make a 3D game that doesn't do this, enough so that going back and doing it the old way, using viewport-relative control, is one of Super Mario 64's key innovations.

Finally, Asteroids is one of the few games that still looks "cool," even to a modern gamer spoiled by texture-mapped light-shaded polygons, because of its Vectorscan monitor. The effect just isn't the same when reproduced on a raster display device. These monitors are no longer manufactured by any company, and are becoming short in supply, so the time may one day arrive that Asteroids in its original form no longer exists.

Prior games maintained visible high score lists, a.k.a. "vanity boards," but Asteroids was the first arcade game to let players enter initials. Unfortunately, the score rolls over at a mere 100,000 points! Twin Galaxies' record for Asteroids rolled it 413 times, over a number of days. This could be considered illustrative of the difference in developer and player perspective at the time.

It may be that the developers didn't see that ultra-long games with huge scores weren't possible, but that they thought no one would bother playing for so long. Contrast Asteroids' complex play with that of earlier games like Pong, and it's easy to see how developer expectations may not have matched with players.

Centipede

1980

Designed by Ed Logg and Dona Bailey.

One of the most interesting things about these games is how abstract they are. Centipedes don't move like this in real life -- going back and forth until they hit mushrooms and drop down a level. In fact, nothing in this game matches its real-life counterpart very well. The game is composed entirely of invented mechanics. This is nothing special in the field of puzzle games, but in a action game, it's novel.

But then, for what is basically a shooter, there's a great amount of strategy to Centipede. The most inert things in it, the mushrooms, turn out to be the key to success. If there weren't mushrooms it'd be easy to clear board after board. It takes time to chip away at them, shooting centipedes creates more, and if there are too few on the screen the game drops in mushroom-producing Fleas.

Meanwhile, mushrooms hasten the centipede's descent, they block shots, they give scorpions something to poison which can make the 'pede much more dangerous, and they even block movement if they're low enough. All four of the game's enemies affect, or are affected by, mushrooms in some way.

Centipede's difficulty curve is also a bit special, for there are actually two curves here added together. The game gets harder by level, in that every time the player clears a centipede the next one is slightly harder, with a faster 'pede and more initial heads, and it gets harder by score, which affects overall game speed and enemy behavior.

Centipede's difficulty curve is also a bit special, for there are actually two curves here added together. The game gets harder by level, in that every time the player clears a centipede the next one is slightly harder, with a faster 'pede and more initial heads, and it gets harder by score, which affects overall game speed and enemy behavior.

This helps to mix things up a bit, and also makes the game less vulnerable to hunting strategies that freeze the level progress but increase score. Although the game still has those...

The distinctive winding motion of the centipede makes possible an amazing exploit. An old issue of Joystik illustrated the technique, attributed to one-time Centipede champ Eric Ginner, demonstrating that by leaving three mushrooms on one side of the screen, both the centipede and any extra nuisance heads will be trapped between them and the side in a constantly-winding blob, leaving the player entirely safe.

Due to the game's per-level difficulty advancement, if this is done on a "full centipede" board, one that starts with no individual heads, then the game will never drop in fleas to bomb the player or add mushrooms, meaning the only things that can hurt the player are the spiders that show up periodically. By just hunting them the player can accumulate high scores with minimal risk, although it's kind of boring to play that way.

Tempest

1980

Designed by Dave Theurer

Tempest is abstract even by Atari standards. Each level is a one-screen web, divided into lanes. The player can move around freely along the outside of the web using a dial, but his position always resolves into being in one of the web's lanes, and shots always travel down the center of a lane.

The web is in perspective, with the player's movement area being at the close end, and the center of the web in the distance. This is where the enemies come from, and clearing a level means destroying all the major enemies on the web.

The primary enemy is the Flipper, a tie-shaped thing that sails out from the distant center of the web towards the rim where the player resides. One shot kills a Flipper, but there's many of them and they're pretty quick, and the player must try to shoot them before they make it to the end.

If a Flipper makes it, it "flips" along the outside of the web, out of the player's reach, and tries to "capture" him by flipping behind him and taking him in, which costs him a life. Flippers on the outside can be killed either with the Superzapper or by shooting just as the Flipper's about to hit the player.

If a Flipper makes it, it "flips" along the outside of the web, out of the player's reach, and tries to "capture" him by flipping behind him and taking him in, which costs him a life. Flippers on the outside can be killed either with the Superzapper or by shooting just as the Flipper's about to hit the player.

The most interesting "enemy" are the Spikes. They don't directly attack the player; in fact, they don't move at all. They start each level on the board, protruding into the lanes of the web from the distant opening. If a shot traveling down a lane hits one, it "pounds" the Spike back a bit, the amount varying according to the level, and a Spike pounded all the way back vanishes.

While they may block shots meant for more aggressive foes, they aren't dangerous until the level is complete. When cleared, the player sails down and through the web, with a 3D effect, to reach the next level. Any Spikes left during the level remain during this sequence, and if the player hits one along the way he loses a life and is sent back into the previous level.

The player can still move and shoot during the exit animation, so the can try to dodge into empty lanes and pound short ones down while exiting, but it's usually better to make sure there are free lanes available when the last enemy is killed... which means there are actually times when it's best not to kill that last foe. One of the enemies, Spikers, has as its purpose in life the growing of Spikes.

Tempest is one of the twitchiest games ever made, requiring total concentration to survive later waves. Most twitch games ultimately use a joystick, sometimes two, because of their familiarity to the player. Player movement in Tempest, however, is ultimately one-dimensional. The player movement zone during each wave is the outside of the web only.

Tempest is one of the twitchiest games ever made, requiring total concentration to survive later waves. Most twitch games ultimately use a joystick, sometimes two, because of their familiarity to the player. Player movement in Tempest, however, is ultimately one-dimensional. The player movement zone during each wave is the outside of the web only.

Since dials are a very analog form of control, the game can throw situations at the player requiring speed and precision where ordinary digital movement would be inadequate, and indirectly helps take the rough edges off the design. If the player's lane is surrounded by enemies he can still escape if he can only twist the knob fast enough, while if he had a constant travel rate there would be more situations that come down to being inescapable.

Link: Interview with the designer of Tempest (unnamed, but obviously Theurer).

Quantum

1982

Developed by General Computer Corporation

Quantum, one of Atari's more obscure titles, has one of those game ideas that seems to float around the game industry, popping up randomly in various places, even though it's unlikely each use was influenced by prior art.

The recent DS game Pokemon Ranger, for example, has play that ultimately can be traced back here, and aspects of it can even be found in Sonic Team's Nights Into Dreams. But Quantum is obscure enough that it's probably not due to a conscious effort to steal -- the idea just seems to suggest gameplay.

In Quantum-style games, the player has a cursor that leaves a trail behind it of limited length. Depending on the game, the trail is controlled with a trackball, joystick, analog stick or stylus. Various enemies litter the screen, moving slowly.

The player's task is to surround them with the trail, making a complete loop and clearing them from the board. Some enemies try to foil the player by attacking the trail, others the cursor. Capturing more enemies with a single loop is worth bonus points. That, by and large, is Quantum.

The control scheme tends to matter a lot to games of this type. This one is controlled with a trackball, and like Marble Madness, the control method is not merely an aesthetic choice here.

The control scheme tends to matter a lot to games of this type. This one is controlled with a trackball, and like Marble Madness, the control method is not merely an aesthetic choice here.

The speed of the ball, combined with the skill needed to manipulate it rapidly, make a big difference to the experience. Arguably, if you aren't playing Quantum with a trackball, you aren't really playing it.

It should be noted that while Atari published this game, its developers did not design it. It was produced by General Computer Corporation, who also made the better-known Atari game Food Fight.

Major Havoc

1983

Designed by Owen Rubin

A lot of what we've come to think of the platformer genre can be traced back to this classic-era, pre-Super Mario Bros. game. Prime innovations introduced here are the ideas that jump height should depend on how long the button is pressed, and that jumps can be controlled while already airborne.

Of course, in real life we all jump more like Simon Belmont in Castlevania -- without any in-air control. Both adjustable-in-the-air height and off-ground horizontal control are unrealistic, added to games to make them more interesting to the player.

They add player agency when none would be expected both to make up for the limitations of the controls (there is no button marked "jump strength") and to allow player reaction speed to make up for failure to look ahead. They make platform games more immediate.

The game also includes multiple routes to each goal, and at the end a Metroid-ish escape-the-base timed section. It uses a Defender-style scanner to show players both an overall map and the location of off-screen threats. In early rounds it shows the player the way using tutorial arrows.

It even includes a form of difficulty levelling: if crashing into a enemy kills the player, on the next trip through that level, the enemy will be gone! This is better than what many recent games to feature "adaptive difficulty" do, invisibly reducing the number of foes, making them dumber, or decreasing their health without telling the player, in effect lying to him about how much better he's getting. At least here, you can see the thing that killed you last time is no longer around.

Another interesting aspect of play is the multiple "modes" for the game. Between platforming areas there are shooter sections. After clearing the space level there's a landing challenge before the platform area begins. There's even a miniature Breakout game playable on the control panel view screen between boards; while only playable for a few seconds each level, the board carries over between levels, and clearing all the blocks is worth an extra life.

So many awesome ideas made it into Major Havoc, and work well there, that it's a real shame that the game didn't do well, its sales curtailed by the crash.

Of random interest.... according to Digital Press' page on the game, the game contains the credits of its creators, but hidden in a very hard-to-find place. In the base levels, try as you might, you'll never be able to find a way to escape the maze and fall out of the level, but there is a very rare bug that causes the player to fall through a wall. If this happens on the outside of the board, he'll fall down through space and encounter the names of the game's staff.

Here's a cool bit of trivia. Sonic the Hedgehog is often regarded as the first platform game to have an "idle animation," where if you don't touch the controls for a few seconds your guy stands and looks at you, tapping his foot. But Major Havoc has a similar idle animation, rendered in its Vectorscan way.

Could it be that the Sonic folks were familiar with Atari's arcade game? It's actually likely: Mark Cerny, designer of Marble Madness, is credited as a developer on Major Havoc and is also a friend of Yuji Naka of Sonic Team!

Link: Major Havoc designer Owen Rubin has a website.

Qwak

1982

Designer unknown

Qwak is a fairly old Atari arcade game planned for release just a year after Asteroids. Functionally it's equivalent to Happy Trails (for Intellivision) and/or Junction, and/or Locomotion. It's barely known about because it's one of Atari's many discarded prototypes.

As with Quantum, it's interesting that this idea has been visited by so many different people. Start out with one of those sliding tile puzzles, the ones with the numbers from 1 to 15 and an empty space into which the player can slide adjacent tiles.

The game board is bigger than that, but instead of there being numbers on the tiles, there's scrambled sections of a path. There's a character somewhere on the board following the path, who it's the player's job to protect. The player cannot control him directly, but by sliding tiles around, he can make a continuous route for him to follow.

The player's job is to do just that, and guide the character to various destinations somewhere on the board, but he loses a life if the character ever runs out of path, either because he ran into the gap or a tile without a matching path.

The player's job is to do just that, and guide the character to various destinations somewhere on the board, but he loses a life if the character ever runs out of path, either because he ran into the gap or a tile without a matching path.

Some versions of this game introduce time limits, multiple checkpoints, "jumps," enemy characters and other complications, but the basic idea is challenging enough. These games can be quite maddening, and Qwak is the hardest of all.

One of the unique things about this version is that the player is actually concerned with the fate of several characters, a small family of ducks (led by a swan) that floats through the game's rivers-and-waterfalls puzzle world. The player only need get one of them to the goal to pass the level, but more are worth extra points, and the excess ducks are meant to be the player's "lives."

This makes the game unforgiving, for the player ultimately has only one attempt to solve each board. If none of the ducks finds a route through, the game ends. Maybe the unknown designer intended this to add longevity, since each level has a fixed layout, but at a quarter an attempt it's not really fair.

There are some other things in there that make it even harder. Each level begins with only a few seconds before the ducks hit a fatal barrier unless the player fixes it immediately, but the game's tiles take a half-second to slide into place.

There are some other things in there that make it even harder. Each level begins with only a few seconds before the ducks hit a fatal barrier unless the player fixes it immediately, but the game's tiles take a half-second to slide into place.

Because of this, there is very little time to spare on wasted moves. And often, the only tile that's near enough to keep the duckies alive is one with a fork in it, which causes the ducks to split up and then forces the player to keep track of multiple paths simultaneously.

So why did this game not make it out of prototype? The era of the game was that of the classic arcade, and while many more games then had puzzle elements than they do now, there were very few explicit puzzle games. And... it is hard. There were lots of hard games then, it is true. Defender was released just the year before, but Qwak's difficulty, combined with its limited player agency, seems somehow less fair.

(By the way... there's another Atari game called Qwak, which more people might be familiar with, which was released eight years before this one. It's a light gun more akin to Duck Hunt.)

I, Robot

1983

Designed by Dave Theurer

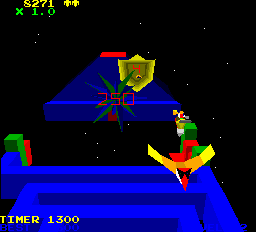

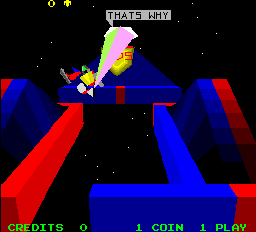

When people find out about I, Robot, the polygonal game released at the tail end of the classic era, jaws tend to drop. It's completely in 3D, right down to having a camera change button, and it was released just two years after Pac-Man. Sure, it's primitive, but as they say, it's amazing that the dog talks at all. This is the kind of brilliance Atari could field in its halcyon days.

And yet, I, Robot did badly in arcades. It could be that it was timing: it was released in 1983, the very year of the crash that marked the end of mainstream acceptance of video games. Atari Games did manage to retain much of its spark through the early 90s, but it set back the cause of 3D gaming for years.

The company tried to make sophisticated games, with unique play mechanics that no one had seen before, while arcades had become the exclusive province of teenage boys, a demographic not exactly known for its discernment.

Which is not to say the game doesn't have other problems. Its hardware had a high failure rate, and the game is abstract and weird -- even by Atari standards. The player controls a robot whose eternal mission is to hover and color all the red spaces of a three-dimensional playfield blue, in order to destroy a malevolent eye that surveys the board.

Moving to the edge of a gap causes the robot to leap across it, and there are lots of gaps to leap across, but the eye has declared that there shall be no jumping. (The game's attract mode demonstrates this humorously.) The eye opens at regular intervals, and if the robot isn't on solid ground at that moment it is instantly destroyed. Jumps are often long, so on some levels this requires some degree of foresight to avoid getting zapped.

Moving to the edge of a gap causes the robot to leap across it, and there are lots of gaps to leap across, but the eye has declared that there shall be no jumping. (The game's attract mode demonstrates this humorously.) The eye opens at regular intervals, and if the robot isn't on solid ground at that moment it is instantly destroyed. Jumps are often long, so on some levels this requires some degree of foresight to avoid getting zapped.

Each level also contains its own unique hazards, and these obstacles are the most interesting thing, design-wise, about it. Each of the first 26 levels plays differently! From destroying green walls with soccer balls to dodging floating sharks to dodging giant beach balls, this is a tremendous amount of variety for such an old game.

When people talk about I, Robot now, this aspect tends to get drowned out in their awe of the technical aspects, but it's the portion of the game that holds up the best. There are shooter sections between the platformer areas, bonus stages every three levels, and per-level best score tracking. There's even a second game mode, a simple art toy called Doodle City, that can be selected instead of the main game at the start of play, though it's kind of pointless.

When people talk about I, Robot now, this aspect tends to get drowned out in their awe of the technical aspects, but it's the portion of the game that holds up the best. There are shooter sections between the platformer areas, bonus stages every three levels, and per-level best score tracking. There's even a second game mode, a simple art toy called Doodle City, that can be selected instead of the main game at the start of play, though it's kind of pointless.

I, Robot actually shares a lot in common with Major Havoc. Both games feature multiple modes, including shooting scenes, platforming sections and tremendous variation between levels. They also both get hard fast.

Link: Here's a list of all the levels in I, Robot.

Marble Madness

1984

Designed by Mark Cerny

Marble Madness was the beginning of a great change in Atari's output, moving both towards standardized hardware and software components. After the split with the old Atari, Inc. after Jack Tramiel bought only the consumer electronics portion of the company, the arcade group was renamed Atari Games. Marble Madness was one of its earliest products, if not the very first.

This was the first System 1 machine, the beginning of a much-revised branch of Atari hardware that served well until around 1991. Even those games that didn't fall under the System 1 or System 2 lines share many hardware similarities with Marble Madness. This was the game that brought us the Atari Font, the Atari Bell, and demonstrated the potential of the POKEY interface chip.

Again, Space Invaders introduced the idea of lives determining the end of a game of indefinite length. Marble Madness abandoned that idea, reverting to a version of the Extended Play mechanic from old racing games like Sprint. In those games, the player was allowed to play until a timer ran out, but if he could reach a target score his game would be extended with a limited amount of extra time.

Marble Madness mixes the two ideas up a bit. You begin the Beginner Race (after Practice, which doesn't factor in) with a set amount of time. The time for each succeeding level is the time left over from the last, plus a large bonus.

Marble Madness mixes the two ideas up a bit. You begin the Beginner Race (after Practice, which doesn't factor in) with a set amount of time. The time for each succeeding level is the time left over from the last, plus a large bonus.

Thus, every second the player wastes comes off the end of the game; every wasted second is its own penalty. It's an idea that has not made tremendous inroads, but it pops up in surprising places: it is just this mechanic that makes Crazy Taxi so addictive.

It seems somewhat strange that Marble Madness is so remembered now. When a game like Monkey Ball, Mercury Meltdown or Hamsterball comes out, the reviewers will invariably describe it in terms relating to Marble Madness.

But the thing about the original game is that it's really short. Six levels is all there are, and the Ultimate Race at the end requires such skilled play just to get to, let alone complete, that most players have probably not gotten through the whole thing, at least on an arcade machine.

The game's legend has spread somewhat from the strength of some fairly good computer and console ports, but those sold in the first place mostly because of the popularity of the arcade original. That's not to say the game is bad by any means, just... brief.

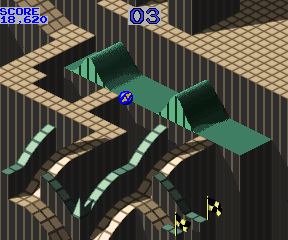

The basic play involves using a trackball to maneuver a ball around a series of geometric landscapes. The landscapes are covered with gridlines, which help the player to get some perspective on the isometric world the marbles inhabit. The cool thing about the ball is that its acceleration is converted directly from the input coming in off a trackball. Roll the ball south-east, and the on-screen ball rolls likewise.

The emphasis is simultaneously on precision, maneuvering the ball across narrow ledges, and speed, for to get the ball to the goal quickly means the player must exert a lot of force on the controls. The force required to get the ball to the end in a decent amount of time both makes Marble Madness an unusually physical game, and means that arcade machines have a very high control failure rate, as trackball mechanisms get busted up by excited players trying to better their time.

The emphasis is simultaneously on precision, maneuvering the ball across narrow ledges, and speed, for to get the ball to the goal quickly means the player must exert a lot of force on the controls. The force required to get the ball to the end in a decent amount of time both makes Marble Madness an unusually physical game, and means that arcade machines have a very high control failure rate, as trackball mechanisms get busted up by excited players trying to better their time.

Marble Madness is another highly abstract Atari concept, but the game's design document, unearthed by atarigames.com, tell us that the game once had a backstory. It was originally intended to bear the name "Omnichron", and be a sport played by people of the 27th century. (This explains the level names a bit, e.g., Practice, Beginner, Intermediate -- they were skill levels of the sport's courses.)

The coolest fact revealed by the document is that, in the original concept, the trackball had motors attached to it, so its motion would match that of the marble on-screen. If it rolled down a ramp and the player didn't want to go, he'd have to fight the motor to stay up there! While an intriguing concept, I'm sure the developers of all those home ports are glad that the designers didn't use it.

720 Degrees

1986

Designed by John Salwitz and Dave Ralston

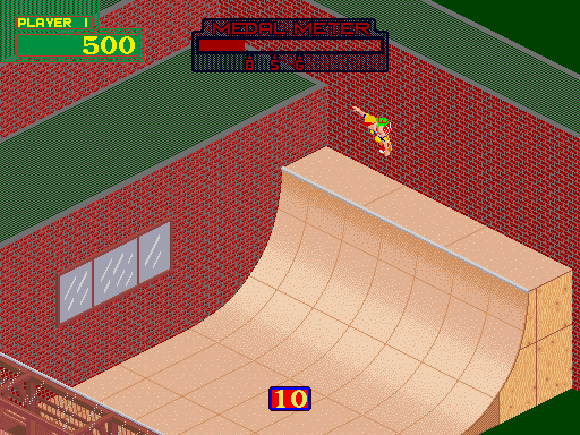

Besides being a predecessor to both event-oriented and free-roaming skateboard games, 720 Degrees has many other fascinating aspects. While its ties to skateboarder culture gave it an immediate audience, its structure is even more interesting and, as far as I know, unique in all of gaming.

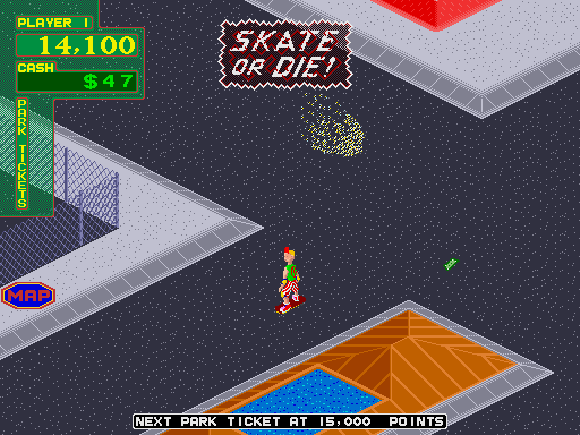

The object of the game is to complete four skate parks, earning as many points along the way as possible. There is no health bar or number of "lives" in the game. Instead, the player is dropped in the middle of a large explorable space, "Skate City," with a machine operator-adjustable number of tickets. He must then find his way to one of the four events located along the edges of the map.

How the player gets there is up to him. It's not hard to make it to an event if he knows where he's going (and maps scattered around help with that), but in order to prosper in the game he's got other stuff to do besides just get to the next area.

There are dollar bills scattered around that are worth small money bonuses, jumps and hidden spots galore that award points when activated, and in the corners of the map shops where collected money is traded for better equipment, which is very useful in later levels.

But the events are most important. The Skate City area is timed, and if the time bar runs out the game declares, dramatically, "SKATE OR DIE!" (The game is unrelated to the early Electronic Arts hit by that name.) This signifies the arrival of the deadly bees, which begin to pursue the player, faster and faster, until they catch him. Getting caught by the bees is the only way to lose the game.

It's not at all hard to skate to an event site within the timer. Shouldn't that make the game easy? Well no, because the game is designed so that everything else puts pressure on the Skate City timer, making working within it, and defeating it as far as possible, the core of the game.

The events themselves, Ramp, Pipe, Slalom and Downhill, are just bonuses: completely failing an event carries no game penalty other than the lack of a bonus. Just the act of entering an event resets the time bar, allowing the game to continue, but there's a catch. The player won't be let into the event unless he has a ticket for entry, and the only way to earn those is by scoring points by whatever means, either from event bonuses or in the park.

Even on the easiest settings, it is difficult to get the points needed to keep earning new tickets within the time allowed. Besides events, the only reliable source of points is doing tricks on Skate City's wide variety of ramps and jumps, and from finding invisible point spots.

Getting better equipment helps the player in making the most of his time by increasing speed and acceleration, making it more difficult to crash after a bad jump, and decreasing recovery time if the player does crash. 720 Degrees' design is tuned to force the player to do all these things to have a chance of finishing all four boards.

To summarize: the only way for the player to lose is to run out of time and get caught by the bees. But only way to reset the clock is to make it into an event with a ticket. The only way to get tickets is to earn lots of points, which requires doing well at events and/or earning points doing tricks in Skate City.

Earning points in the city takes time however, and time is also needed to get to the shops for better equipment that makes earning event points, so the player must also learn quick navigation and travel skills.

It's a little confusing to understand at first, so the game pops up help messages if the player's in danger of losing due to having no ticket. It turns out to be a very effective design. Each piece of the chain is just unfair enough that even good players will find themselves lacking if they concentrate on one link only.

The timer is the only real danger, but to survive it the player must master navigation, upgrade strategy, each of the four special events, and trick performance on the run between destinations. The result is that, while it's ultimately a skateboarding game, the game is interesting even to people who have little interest in shredding.

The reason it works is that the player doesn't have to understand all this in order to play. So long as he just skates along, finding points, doing tricks, and is making it to and doing well in events, the game continues. Doing better at any one of these things will ultimately be felt in reduced time pressure, so players get better quickly with practice. But with 16 events to complete, a lot of practice indeed is necessary to finish.

Finally, it's possible for operators to enable a continue feature for the game, but it's unusually harsh. The player may only continue up to three times. After a continue, the bees vanish, the time bar refills, the player's character gets back up, and if he doesn't have one, he's spotted a ticket.

But the ticket is a loan, not a gift! The score needed for the next ticket is increased one award level when this happens, meaning that the player must do very well at the coming event to earn enough points to make up the deficit or he'll have to continue again in short order. This means that it's not possible for a player to just continue his way to the end of the game; a high degree of skill is still necessary, for he needs 16 tickets in order to win and the game will only spot him up to three.

Tetris (Atari Games)

1988

Original design by Alexey Pajitnov, developed by Kelly Turner, Norm Avellar and Ed Logg

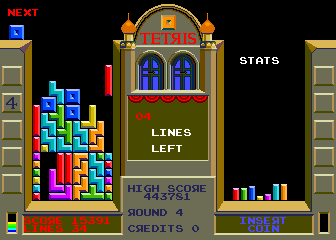

Many companies have tried their hand at a port of Tetris. In arcades, the ports that get the most buzz include those by Sega and Arika. Yet there remains much to recommend Atari's port of the game, long the standard in U.S. arcades, for its inventive special features like advancing lines, appearing blocks, and pre-existing stack levels.

Its excellent music, Russian dance animations, and other touches like using high score names as levels are also appealing. Tengen's fabled NES version of Tetris, generally superior to Nintendo's but chased off of shelves by the courts, was based off of Atari's arcade game.

Now, Atari Tetris is not flawless. The joystick control lacks the sharpness that most Tetris ports have and that makes the game more difficult at later levels, which keeps the difficulty up since the game's speed never gets as fast as other versions. But it's a solid port, with plenty of charm and interesting variations on the game on higher levels that vary it a bit without turning it into a game removed from the Tetris concept.

Some more recent Tetris games try to hook players by drilling deeper into the game's concept, especially Akira's Tetris: The Grand Master, a move which helped to attract hardcore players. Yet Tetris is a populist game, one that lots of people play who could care less about 20G or standardized piece rotations.

Some more recent Tetris games try to hook players by drilling deeper into the game's concept, especially Akira's Tetris: The Grand Master, a move which helped to attract hardcore players. Yet Tetris is a populist game, one that lots of people play who could care less about 20G or standardized piece rotations.

Because of this, I consider this the definitive arcade Tetris, even in the face of modern revisions like The Grand Master, for while that series is well thought-out, and commendable for breathing more life than one might think possible with such a simple concept, they are still games which geek out a bit too much about the idea of Tetris. It was originally a very casual kind of game, played by everyone, and Atari's Tetris is a casual kind of arcade game.

One interesting thing about the game... watch the game demonstration in attract mode and it becomes obvious that the game doesn't demonstrate play using pre-recorded inputs, but actually contains a capable computer Tetris player. They needed this because one of the boards used for attract mode contains the initials of the top scoring player in blocks, so in order to depict realistic play they needed a program capable of responding to varied situations.

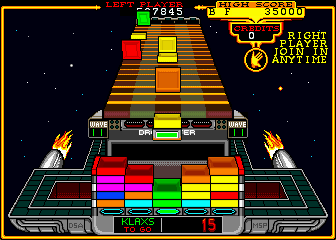

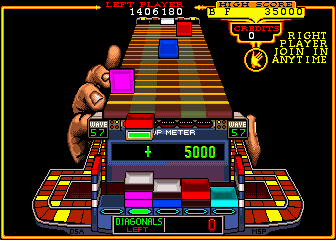

Klax

1989

Designed by Mark Stephen Pierce and David S. Akers

After Tetris, Atari tried a couple of other arcade puzzle games. The most famous of them was Klax, a game with an amazing amount of style, with its "It is the nineties and there is time for...." slogan, T-Shirt offer screen, pop art aesthetic and tremendous array of backgrounds, which are there for no reason other than to be awesome.

Yet the game is interesting for other reasons too. It is fundamentally a Tetris-like game, yet it doesn't look like it at first. Instead of a bin with falling blocks, the player must catch colored tiles coming in off a conveyor belt, then drop them into an abbreviated bin. Both catching and placement are determined by the paddle's X-position at the conveyor belt's edge, so survival and intelligent play are a bit at cross purposes.

Once tiles are in the bin the game works a lot like Columns, in that the player is trying to get horizontal, vertical or diagonal lines of the same color. But the player drops single pieces instead of triples, and the bin is only 5x5 so careful thought is needed to avoid screwing things up irreparably.

The game also features combo scoring like practically every other post-Tetris puzzle game, but is unique in that combos are limited by the bin's small size. It takes a some thought just to figure out what kinds of combos are possible.

The game also features combo scoring like practically every other post-Tetris puzzle game, but is unique in that combos are limited by the bin's small size. It takes a some thought just to figure out what kinds of combos are possible.

The game softens this a bit by letting players move and even drop tiles during the short delay while a Klax is being recorded, which are recorded as a combo if this produces another line of three. One type of Klax, the five-tile vertical, can only be made this way.

Klax gives the player lots of ways to mess up. The paddle can hold up to five tiles, and the uppermost tile can be thrown back onto the belt, but unless the player is careful there's a good chance it'll end up parallel to another tile, making it impossible to avoid missing one or the other.

The player is unusually beholden to the randomness of the blocks that come down, even more so than in other color-matching block games, because the bin is so small. There is no good way to keep more than six potential lines open at once, yet later levels can have up to eight different colors to sort through. In other such games wild pieces, that match any color, are an occasional bonus, but Klax players come to rely on them.

In order to do well at it, players must procrastinate in dropping in tiles, waiting to see if there are any other of that color coming in off the conveyor belt. Dropping in a single color when there's no guarantee that a second or third will come any time soon is a big error.

Waves often start with the player saving tiles on the paddle until at least a pair of the same color is visible. To activate a "secret warp," which requires constructing two five-tile diagonals crossing in the center, this tactic must be taken to extreme lengths.

One aggravating aspect of Klax is that the game, much more than other games of the time, makes its advancing difficulty too explicit. Klax is lost when the player fails to catch the tiles coming in; if he misses too many, the continue screen appears. To stay in the game, the player must always be putting tiles into the bin to make room on the paddle. Hopefully he's using them to make Klaxes to clean out the bin, but that's actually secondary to the tile catching game.

One aggravating aspect of Klax is that the game, much more than other games of the time, makes its advancing difficulty too explicit. Klax is lost when the player fails to catch the tiles coming in; if he misses too many, the continue screen appears. To stay in the game, the player must always be putting tiles into the bin to make room on the paddle. Hopefully he's using them to make Klaxes to clean out the bin, but that's actually secondary to the tile catching game.

The problem is that the paddle movement speed is fixed (it's joystick control, not a dial), and the conveyor belt, if enough time passes in a level, eventually gets too fast for even a perfect player to keep up. This, by itself, is not really terrible; it's just another version of a time limit.

However, over the course of the game's 100 waves each is more difficult than the last, in the time-honored way of arcade games. And each wave also gets faster as it continues. But there is yet another factor at work. The game adds to this an effect called "ramping," by which the game gets faster at a steadily-increasing rate in addition to the increasingly difficulty of the levels.

Ramping only resets when the player expends a credit to continue, but the later levels are difficult enough, and so vulnerable to bad luck, that the player can easily lose anyway. Once ramping is added in some levels end up impossible, too fast to possibly catch all the tiles before the procession becomes overwhelming, unless the player expends a credit to get the speed back down.

S.T.U.N. Runner

1989

Developers include Ed Rotberg, Andrew Burgess, and Sam Comstock, among others

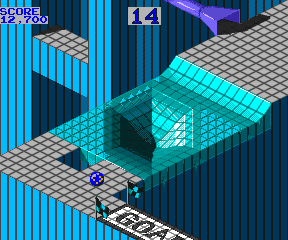

S.T.U.N. Runner saw arcades some time after I, Robot and Hard Drivin', but it still qualifies as an early 3D game from our perspective. Although its frame rate would make it seem unplayable today, people put up with it at the time in exchanged for its then-impressive polygonal graphics.

Basically the first high-speed hovercraft racer, this game is the spiritual forefather of Wipeout and F-Zero. Unlike those games, S.T.U.N. Runner offers a less competitive take on racing. There are no physical opponents in the game; the game leaves the competition to the score lists (every level has a vanity board), and quick finishes are rewarded with points and extra time on the next level, as in Marble Madness.

Notably, the game doesn't contain a speed control or brakes. The game assumes that players will constantly want to go as fast as they can, and is designed with that assumption in mind. There are three basic tasks players must do to keep their speed up.

First, they must avoid the obstacles, usually track walls and enemies. If they can't be avoided then they must be destroyed, with either lasers or with a limited-use "Shockwave" smart bomb-like weapon (which doesn't fail to impress even today). Shockwaves are awarded for flying over many bonus spots in a single race or collected outright off the track's surface.

Second, there are zippers at various spots on the track that provide a great speed boost when traveled over. Hitting consecutive zippers is often difficult, but provides for much better times and good score bonuses.

Finally, and subtly, in the frequent twisting tube sections that make up much of each level there is an optimal path that naturally provides the best speed for the player's vehicle. This path is the line on the tunnel wall that the actions of centrifugal force and gravity would cause the vehicle to drift towards: if the tunnel turns left, then the fastest speed comes from being on the right side of the tunnel, and vice versa.

The tighter the turn, the further up the tube's wall the player wants to be. The game shows the player what the best path is in a tutorial course at the start of the game, and throughout bonuses tend to be located on the path most often. Unlike the many games that reward risky or showy play, in this scheme, players who chase bonuses naturally learn to become better players.

Perhaps the most awesome feature of the game comes at the very end. Every level has a best time score table entry, but the final level's entry is special. The last level cannot be completed; it's an infinite course.

The player's goal is to get as far as he can in the time allotted. As he progresses, the names of the five players who got the farthest float in the air throughout the course, at the spot where they ended up after time ran out. So, to pass another player's skill in the game means literally passing their name in the final level!

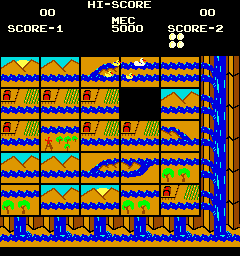

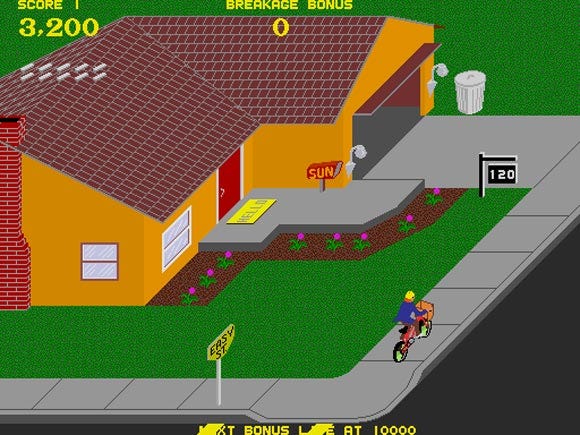

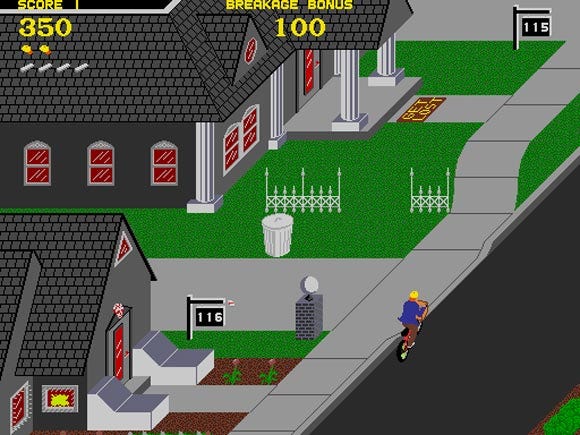

Paperboy

1984

Designed by John Salwitz, Dave Ralston, and Russel "Rusty" Dawe

Paperboy, at first, seems like a simple game of rote memorization and reflexes, but the strategic decisions lend the game more depth than it has to have. This may be the prime connecting element between all of Atari Games' titles: few of the company's games come down to raw reflex testing. There's typically an element of strategy buried there somewhere.

Lots of arcade games have taken the save-the-world approach to play. Like blockbuster movies, they turn up the volume, use tremendous explosions, and tell the player that the fate of the world rests on their shoulders. Atari sometimes took just the opposite approach: all Paperboy requests of the player is to survive a week of running a paper route in the most hostile neighborhood on Earth.

Fundamentally, Paperboy is a shooting gallery game. The screen scrolls unstoppably, ever diagonally up and to the right, while houses go by on the left. The player can change velocity and steer, but can't ever stop, much like a real bicycle. He throws papers with a set velocity in attempt to hit the delivery spots on each house, either the doorstep or the paper box.

The game doesn't directly keep the player away from his targets: there is no invisible wall in place. In practice, however, the house lawns are so cluttered that driving over them is suicidal. The basic strategic tradeoff of the game is this: the closer to the houses the player rides the easier it is to hit targets, but the more likely it is he'll crash, which costs him a bike.

Paperboy has dual survival requirements. If the player runs out of bikes the game is over, but it also ends if he runs out of subscribers. At the beginning of each level a map of the route is displayed with subscriber houses marked, and during play subscriber houses are painted white.

If the player fails to land a newspaper on either a doorstep or paper box, or if he breaks something on the property with a paper (especially windows), then at the end of the day the subscriber is lost.

One interesting thing about this is that, as the number of subscribers goes down, the game gets easier. The player only needs one house to remain in the game, and if the player focuses on it one house is not tremendously difficult to keep. The obstacles make up for this by greatly increasing in difficulty as the week continues, and keeping more houses means more delivery points, and progress towards the scant extra lives offered.

Another strategic decision the game forces on players concerns the paperboy's limited paper supply. He begins each route with ten papers in stock, with refills available on the route. In addition to allowing him to complete deliveries and earn points, newspapers are also the player's only weapon, capable of stunning many mobile obstacles.

Paper caches tend to be on the sidewalk, and the bike's limited maneuverability means the player must begin steering towards a pickup early to reach it in time, further reinforcing the need to stay relatively distant from the houses.

Vindicators

1988

Developed by Kelly Turner, Norm Avellar, and Rusty Dawe, among others

This is a very nifty little game. As mentioned previously, it revives the Battlezone dual-lever control scheme with overhead-view shooting action play. Instead of roaming a vector-screen virtual landscape however, the game has a vertical-scrolling overhead view.

Mastering the controls is a big part of the game, even bigger than in the vector classic, since the player doesn't have the intuitive aid of a first-person view. Additionally, the tank has an independently rotating turret, which itself causes its own share of confusion. The game can be entirely completed without rotating the turret, but many enemies are easier if this control is mastered.

About those enemies, none of them would really be all that difficult if the player weren't in a vehicle that drove, well, like a tank. Vindicators is ultimately about mastering the controls then using them to attack the enemy as safely and quickly as possible.

The two primary types of enemies, tanks and turrets, each apply pressure to the player's control skills in a different way. Turrets can't move and shoot in a predictable, periodic manner, but are each vulnerable only at specific times.

"Number" turrets track the player, and can only be shot when they are open which is the same moment when they fire. "Spinning" turrets rotate until they point at the player, at which time they freeze and fire off a shot.

Both styles are interesting because they place the player in greatest danger at the only moment they are vulnerable to shots. Enemy turrets are the main reason the tank's own turret controls are so important; being able to shoot in a direction other than the one the tank is moving in lets the player perform "drive by" attacks.

Both styles are interesting because they place the player in greatest danger at the only moment they are vulnerable to shots. Enemy turrets are the main reason the tank's own turret controls are so important; being able to shoot in a direction other than the one the tank is moving in lets the player perform "drive by" attacks.

Enemy tanks are relatively weak, but can move and track down the player, and many require several shots to destroy. A few also carry floating mines that detach when their bearing tank is destroyed and chase the player. Mines are actually a fairly major source of points, for the score awarded for shooting one is proportional to how close they are to the player when shot. Good scores on a level are rewarded with extra fuel at the end, so this is more than just a bonus opportunity.

Unlike games produced for PCs and consoles, arcade games are not allowed to be too easy. The operator relies on there being a good turnover rate of players in order to keep earnings up. But this cannot be taken too far, or players will stop playing early.

Eugene Jarvis, creator of Robotron and co-creator of Smash T.V., in an interview for Midway Arcade Treasures, expressed this tension in terms of screwing the player over, but not too much. Vindicators has relatively well-balanced difficulty, and while it's not as famous as Marble Madness or Gauntlet, is one of Atari Games' better productions of the time.

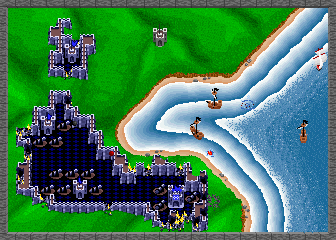

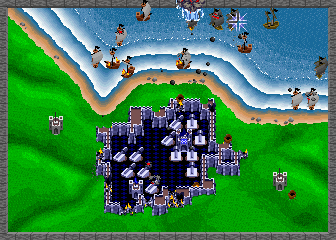

Skull & Crossbones

1989

Designer information unavailable

Skull & Crossbones is a forgotten game. Not one of Atari Games' bigger hits, it's difficult to control and requires lots of money to get to the end, unless the player learns the twitchy swordfighting scheme, and even then it's easy to feel screwed over. Up to two players take to the seas at once in attempt to defeat an evil wizard.

The game alternates between ship levels, where the player boards opposing vessels and defeats pirates and enemy captain, and island levels, which have considerably more variety in dangers. Ships are generally easier, and provide extra health pickups, but islands have more treasure.

I mentioned the annoying control, and I really should elaborate on that. Player control consists of a joystick and two buttons, Turn and Sword. The players' pirates can attack in either direction from either facing by using the joystick in conjunction with the Sword button, but can only defend forward.

The game's attract mode illustrates how players are supposed to defend from sword blows and attack enemies high and low and using backstabs. Tapping Sword and forward or back at the same time performs reaching attacks, while holding the button down and moving the joystick up or down guards in those directions. That's how it's supposed to work, but the jerky animation and weird, laggy walking make it difficult to utilize this knowledge effectively in the game.

One of the things Skull & Crossbones does well is style. It took what is a fairly simple swordfighting game and gave it a thick coat of Pirate Paint, and this is best illustrated by the treasure hoard screen. Here, the player is given a more tangible measure of their success than just a score. At the start of the game the player begins with an empty hold on their ship, which is shown at the bottom of the screen between levels.

As the player collects various pieces of treasure by digging it up and finishing levels, it's not just added to the player's score, it's moved to the hold screen, where it piles up over the course of the game. The amount of loot varies according to how dedicated the player has been at digging it up and which path he's taken through the game, with harder difficulties being longer but providing much more booty.

When the Evil Wizard is defeated, all the treasure the player has collected during the game is displayed, from magic crowns to mere piles of coins, while initials are entered. It was a nice touch.

Unfortunately, collecting that booty is a bit problematic. Throughout the island levels are scattered Xs on the ground that the player can dig up by standing on them and pressing Sword. Once the digging begins, it happens automatically; the player can move on and kill enemies while invisible mates, I presume, do the digging. After a length of time proportional to its worth the treasure will be dug up and the player can collect it by walking over it.

It's an interesting mechanic because like most arcade games, each level in Skull & Crossbones is timed. The player has far more than enough time to get to the end if all he does is kill enemies, but digging up treasure takes extra time, and if time runs out the player's health shifts into Gauntlet mode, emptying one unit per second.

The game encourages players to be greedy to fill the hold screen, and messages after each level tell how much wealth was missed, but the game's one-way scrolling is eager to move Xs off-screen unless a pirate is standing at the edge blocking it, so in the end it feels like being nagged over something the player really has no control over.

The difficulty system could stand a little elaboration, being unusually flexible even by Atari standards. At three points in the game, the player is asked to choose a difficulty. All difficulties go through the same areas, but if easier routes are chosen the player gets abbreviated versions of all stages, enemies have less health, and they telegraph their moves further in advance.

Once a hard difficulty is chosen at a route, easier difficulties are removed from later selection screens, and if the players pick hard at the first choice they're locked into hard mode the rest of the way. (They are rewarded for doing this, however, by being able to find treasure that provides invincibility during much of the boss rush in the final level.)

Skull & Crossbones has many cool ideas in it, but in the end the spastic movement just makes it frustrating. Other, more polished games that were much easier to control were populating arcades at the time. Konami's fondly-remembered, oily-slick Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles came out the same year. Sitting alongside its responsive action and smooth animation, Skull and Crossbones must have seemed grossly inferior.

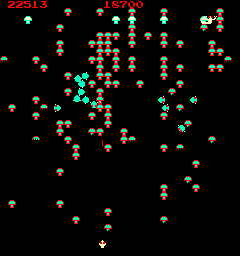

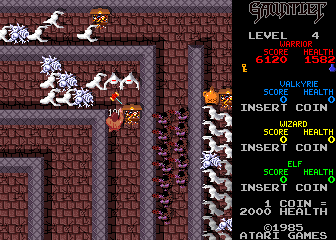

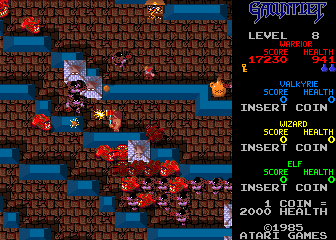

Gauntlet

1985

Designed by Ed Logg

Gauntlet did as much to further the design of arcade games as Space Invaders did long before. While not as popular as the marching aliens were in the day, it was a huge hit relative to the competition. Believe it or not, was the first game to give us drop-in-anytime style multiplayer in the arcades, one of those innovations that seemed so useful afterwards that the great majority of arcade multiplayer games since have nicked that feature for themselves.

The play is fairly simple, even if given the veneer of a Dungeons & Dragons theme. Players pick one of four characters, with differing strengths, to roam around 8-way scrolling dungeon levels, looking for the exit.

Instead of lives they have a numerical health total, that depletes over time at about one hit point per second, and more quickly when taking hits from the enemy. Putting in more coins adds additional health, and the vanity board is average score per coin instead of overall.

Around each level are many enemy generators, out of which pour a flood of monsters. The players can both shoot (with a fire button) or just run into enemies to damage and kill them, but at best this merely holds back the flood. To survive, they must get to the source and destroy it, which requires finding ways around, or through, the enemies in order to get their shots to the target.

Around each level are many enemy generators, out of which pour a flood of monsters. The players can both shoot (with a fire button) or just run into enemies to damage and kill them, but at best this merely holds back the flood. To survive, they must get to the source and destroy it, which requires finding ways around, or through, the enemies in order to get their shots to the target.

A small variety of opponents infests the levels, with a good mix of abilities: some shoot, some are difficult hand-to-hand, and some can throw rocks over walls. Each level provides monsters in different proportions, and the game is basically an endless assortment of such situations. Doing well involves responding to each efficiently, and dealing with each with a minimum of health loss.

And that's roughly it; there's no storyline at all. There's a bit of strategy involved in getting food, collecting permanent ability potions, and defeating the Thief (a special enemy that follows the players' exact steps through the level until he reaches them), but the main play really doesn't change much as the game goes on.

According to GameFAQs, there are 100 boards in Gauntlet's cycle. The first seven are always the same every game and serve as an introduction. After that, the player begins getting levels in what I'll call the loop, a long cycle consisting of the bulk of the game's maps.

According to GameFAQs, there are 100 boards in Gauntlet's cycle. The first seven are always the same every game and serve as an introduction. After that, the player begins getting levels in what I'll call the loop, a long cycle consisting of the bulk of the game's maps.

The loop is sequential, but when level 7 is completed the player could end up anywhere along it. When a game ends, the machine remembers the loop level it ended on, and that board becomes level 8 in the new game, which re-enters the loop at that point.

The loop has an interesting character to it. There are both easy and hard levels in Gauntlet, and there are runs that provide several easy ones in a row as well as challenging ones. If a new game enters the loop at the right place, players could collect a windfall of food and manage to play for some time. If the loop is entered at the wrong place, it could be tough going for a while.

In any case, what's important to remember that it is truly a loop -- an endless cycle. There is no ending to either Gauntlet or Gauntlet II. You could loop many times and it won't end. Word is that someone has looped the game three times on one credit, just to be sure. Gauntlet II scrambles the levels in various ways as it goes, but there's still just 100 of them.

The fact that there's no ending, however, points out a very important difference between Atari's view on video games and the current perception. Atari saw Gauntlet as a process, a game that was played for its own sake and not to reach completion. The adventurers continue forever until their life drains out, their quest ultimately hopeless.

Gauntlet was a huge hit for Atari at the time of its release, but this endless play concept doesn't appear to have aged well. I find it interesting, in games of Gauntlet I've had with other people in the past few years, that their interest tends to survive only until the point where they learn there is no ending. Times have certainly changed.

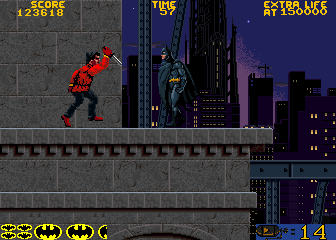

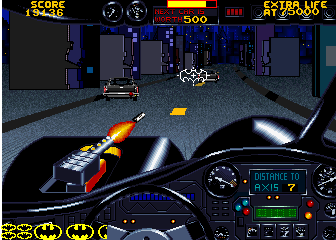

Batman

1991

Developed by Team Numega

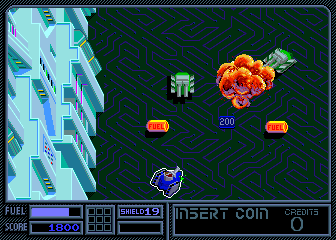

I don't wish to give the impression that Atari Games could do no wrong. They had a few less interesting games mixed in there. There was a class of arcade game, right before Street Fighter II hit, just as ROM space was getting large enough to hold some slight amount of multimedia, that existed merely to immerse the player in some licensed property, announcing its theme song in attract mode, scattering its indicia through the game's UI, and presenting itself as a playable version of that license.

Konami arguably did this best with Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Atari's Batman is an attempt at the same kind of thing, but it was nowhere near as successful.

Not one of Atari's more-fondly remembered titles, this a painfully dated adaptation of Tim Burton's movie, coming at that time when side-scrollers like Double Dragon dominated arcades.

Not one of Atari's more-fondly remembered titles, this a painfully dated adaptation of Tim Burton's movie, coming at that time when side-scrollers like Double Dragon dominated arcades.

Using an engine very similar to ThunderJaws, itself not one of Atari Games' better products, it's a clunky mish-mash of concepts, with stiff jumping and pointless driving and helicopter sequences. Also, like ThunderJaws, the platform areas take a lot from Namco's Rolling Thunder, right down to enemies emerging suddenly out of background doors.

It's loaded with music taken from the movie, digitized portraits between scenes, and an abundance of character quotes. Playing the game now, it's hard to imagine there was ever a time when hearing Jack Nicholson saying "Didja ever dance with the devil in the pale moonlight?" was cool. Movie stills are used between levels as a player reward in a way that, alas, mirrors the use of video clips in more recent movie-to-game adaptations.

But let's stick to the gameplay here. Of the ill-considered ideas at work here:

The player cannot see very far ahead, relative to his size, causing lots of cheap deaths. The gray-suited opponents take the worst advantage of this, possessing both a bomb-throw move that travels in an arc and a gun that shoots at head-level. The proper response to the bomb is to jump, and the response to the gun is to duck.

In this case, the enemy's distance from Batman is what gives the player opportunity to react, but the screen is just too small to allow for enough of that. Of course the player could just keep trying until he lucks through, but that's not really fair, especially when lives end so quickly and cost 50 cents each.

Enemies fire off shots quickly and without many frames of animation for reacting. This, combined with the frequent use of reaction-based dodging, tends to make Joker battles particularly frustrating, seeing as they rely on exactly this kind of react-to-the-attack play.

Lots of piddly background details turn out to be lethal. In the second platforming level, there are nozzles on the ceilings and on pipes that look like purely decorative, but turn out to cause damage. The ceiling nozzles are particularly bad, as their bullets are only three pixels wide! Considering that the only notification of damage is Batman flashing white for a split second and a generic digitized grunt, and you could be forgiven for not even noticing you'd just lost a third of your health.

The final level has both cracks on the ground that are less than half Batman's width yet turn out to be deadly pits, and bells hanging from off-screen overhead that turn out to be instantly deadly when they land on Batman's head.

Some enemies, especially the Jack-in-the-Boxes, can end a player's credit from start to finish all by themselves despite being minor enemies. If you get close to a Box and don't kill it instantly, then your life is basically over.

Some areas have tremendous vertical scrolling range, but finding the place to jump up to can be difficult, especially since Batman's jumping height magically extends only sometimes when up is held on the joystick.

There is some good to be found here. Strangely for a narrative-based license game, but not for Atari Games, Batman puts high emphasis on score. The scoreboard is per-credit, not one-credit or overall, and large awards are granted in driving and helicopter levels for perfect performance. A couple of the platforming levels actually have what amounts to multiple routes through them, although they're uniformly deadly.

There is some good to be found here. Strangely for a narrative-based license game, but not for Atari Games, Batman puts high emphasis on score. The scoreboard is per-credit, not one-credit or overall, and large awards are granted in driving and helicopter levels for perfect performance. A couple of the platforming levels actually have what amounts to multiple routes through them, although they're uniformly deadly.