Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Unsung game designer Hirokazu Yasuhara, one of the 'original three' behind Sonic The Hedgehog, also helped make Western titles like Jak & Daxter and Uncharted - and gives Gamasutra a fascinating lecture on game design and fun.

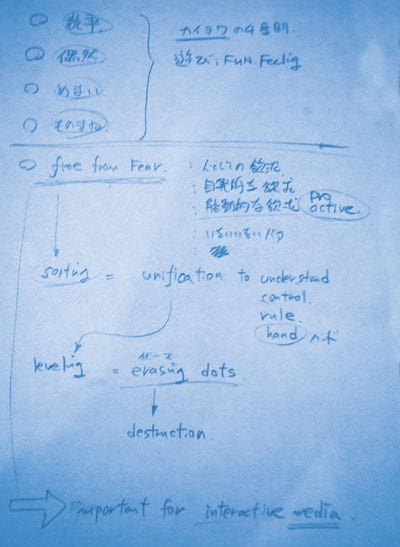

[The most recent issue of Game Developer magazine printed a truncated version of this interview with Namco Bandai Games America senior design director Hirokazu Yasuhara. Gamasutra is proud to present the unabridged version. Yasuhara has a great design philosophy which he espouses here, complete with his original notes and illustrations, alongside a history lesson on the Sonic series.]

Hirokazu Yasuhara is one of the great unsung heroes of game design. He is currently senior design director at Namco Bandai Games America, and before that he held the unassuming title "game designer" at Naughty Dog, having most recently shipped Uncharted: Drake's Fortune -- but his history is inexorably intertwined with the history of modern character game development.

Yasuhara was the chief level designer on the original Sonic the Hedgehog, as the third person to join that team after Yuji Naka and Naoto Ohshima, and played a key role in the fleshing out of that seminal title, as well as a number of its sequels. He was responsible for the first 3D Sonic game, Sonic R, and was involved in the Jak series for Naughty Dog since the first sequel.

In this extensive interview, Yasuhara outlines his carefully constructed theories of fun and game design, including the differences between American and Japanese audiences, with illustrated documents. After conducting this interview, I was convinced that he should write a book based on his theories. Until then, consider these words to be sketches -- a preamble to that necessary work.

I heard that you still use graph paper for all your level designs and things like that. What is your process for designing at this point?

Hirokazu Yasuhara: Actually, I stopped using graph paper to make the level. [pointing out some paper materials] I use this to work out all the gimmicks [ie. the unique features to each level], but I threw some small, easy --

Can I take a picture?

HY: Actually, no. (laughs)

It's so cute. I want that.

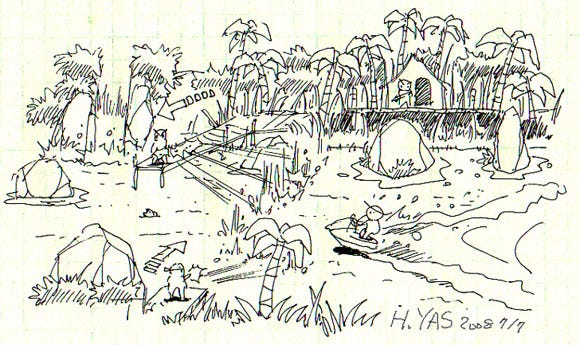

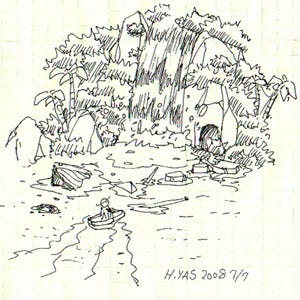

HY: So I come up with some ideas about events that are happening; how the player acts, you know, at each stage. What kind of results happen once you perform this or that gimmick in each level. For example, in a jungle stage, you would use...

So these are small bits of design concept, like moments that you could use? I see.

So these are small bits of design concept, like moments that you could use? I see.

HY: Mm-hmm. So I come up with some ideas for the programmer to work with, and they decide what's good and what's impossible to implement, based on schedule or programming difficulty.

So it's more high-concept design, and then they narrow it down?

HY: Yeah. So this is the idea for a section, and I make a picture or a scan of what kind of image I have going, add some simple comments, and make a document that I bring to the artists and programmers. These are all concepts. I make a lot of ideas and inserts. And this is what I just created. I don't write the map by hand anymore; I use Illustrator instead to do the map. It has about five layers.

Do you think of ideas and then put down whatever comes to mind, and then is it you that shrinks it down to the actual design that it'll be, or is it other designers?

HY: I shrink it down by myself, actually. It's up to the schedule, so... (laughs) If the artists or programmers say "no", then that's the answer. So it's kind of a mix. I always try to push a can-do attitude with them, you know? (laughs) For the programmer. But sometimes, you know...

How do your ideas come from these individual moments into the full art of game game design?

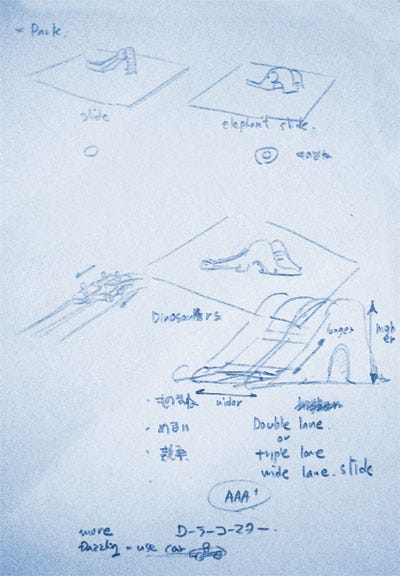

HY: So I always think about all the different elements of what makes something fun. This formula is made by a sociologist from France who did some thinking into what it is that makes something fun, or interesting, for people to experience. One of the things is competition. The next is happy coincidences; a gamble that pays off, that kind of thing. Following that is dizziness or exhilaration, and the final thing is imitating, or copying.

For example, let's say we go to a theme park one day. There are two slides there: a regular metal slide, and one shaped like an elephant. Which one is more attractive to a child? It'll usually be the one with the elephant, because the form of "imitation" that it represents is more interesting to the eye. That, in itself, is enough to make it fun.

For example, let's say we go to a theme park one day. There are two slides there: a regular metal slide, and one shaped like an elephant. Which one is more attractive to a child? It'll usually be the one with the elephant, because the form of "imitation" that it represents is more interesting to the eye. That, in itself, is enough to make it fun.

So what happens when you put all of these factors together? Well, if your park's trying to improve its business, then maybe it'd try to make the slide a longer or faster ride, or maybe make it bigger and shaped like a dinosaur so it'll be more fun for the kids.

Maybe they'll make it a dual slide so kids can compete with each other to get to the bottom faster -- add a competitive element.

If they keep going with it, it'll get big enough that it winds up becoming a log-flume ride or something -- but there's still more you can do, like maybe put wheels on the logs and make it look like a car.

It's a continual process to make it more fun. So the more you think about the externals of something, the more grandiose it'll wind up being. You'll wind up with a roller coaster eventually -- and then you'll make it rotate or something, if you think it'll improve business. That is one of my basic principles.

Another important thing is to consider the basic desires of people, even if all you're thinking about is a simple game. For example, you have active desires -- "Freedom from Fear", as they say, the way people actively want to avoid fear in their lives. And one way they deal with that is by engaging in a sorting process.

Let's say that you have a flat surface with some bumps sticking up out of it. Most people would want to see those bumps removed, as a sort of equalizing or "beautification" process. Also -- you know the game Othello, right? A lot of the fun in that game is the exhilaration you get when you flip a lot of pieces and make more of the board your color. Tidying up things, in a way.

It's the same thing even in business -- it's nicer when you have a well-organized Excel spreadsheet then a cluttered one. It's a continual process of actively sorting and bringing things under control, and the reason why people do this is because it helps make life simpler for them -- the process itself is fun, too.

As for how this goes back into video games, one thing you see a lot of in games is the act of "erasing," or "destruction." For example, in Pac-Man, you're eating dots -- wocka-wocka-wocka-wocka. That is erasing, and it's also a form of destruction. You're destroying everything in your path, and you're leveling out the entire playfield.

This is something that I think is vital for any interactive experience -- that sort of proactive desire in motion. This manifests itself in a lot of ways; the player can satisfy this desire a lot of ways in a lot of different games.

This is something that I think is vital for any interactive experience -- that sort of proactive desire in motion. This manifests itself in a lot of ways; the player can satisfy this desire a lot of ways in a lot of different games.

But there's something else involved here: creation. Some people get what they want via destruction, but others do it via creation instead. For example, if I am feeling vulnerable, then I get more friends or party members, if you will, and make myself more protected -- or I go to town and interact with people to get that same feeling.

By the same token, some people think in the opposite way -- if I kill every enemy in the area, then that logically means I'll be more secure. "Fear" at play. It's different ways of arriving at the same emotion.

That kind of mindset is more interested in "deleting" their enemies. So, like, Pikmin versus Gears of War. In Pikmin, you gather allies to complete objectives or defeat enemies; in Gears you just kill everyone in an area, and then that area is clear of monsters.

HY: Yeah, exactly. And this process keeps repeating itself. You see some cultural differences come to the surface with this, too. For example, a lot of Japanese people attain a feeling of security via creation, or making themselves look nice, or saving money. Not that Americans or Europeans aren't like that, but Americans may be more likely to take a more "destructive" process toward feeling safe.

I think a lot of that is because the things that you "fear" can be very different between nations -- not real, palpable fear, but more the lack of feeling at ease with yourself.

I think a lot of that is because the things that you "fear" can be very different between nations -- not real, palpable fear, but more the lack of feeling at ease with yourself.

Something you don't like very much; something that stresses you out -- another word for "stress", really. And since sources of stress can be different between Americans and Japanese, it follows that the methods both populations take to relax would be different, too.

One more important thing I want to bring up is that when people achieve freedom from fear, that in itself makes them feel happy. You aren't stressed out anymore, and that cheers you up. I use that a lot in my game design, because it's a very basic and important.

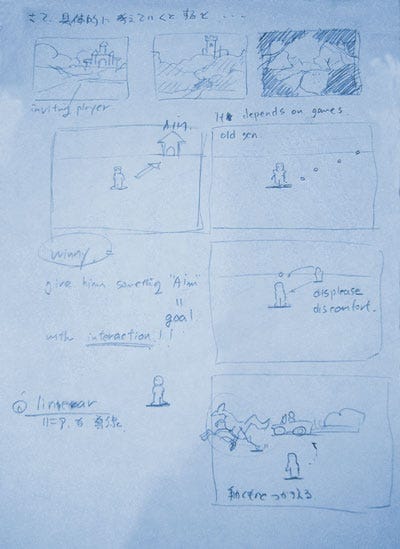

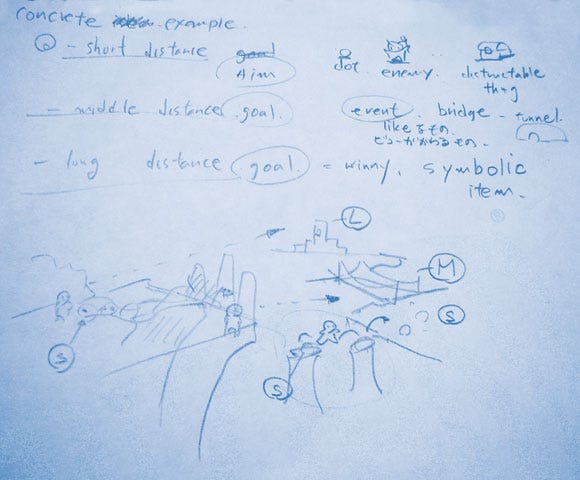

Another thing is that, putting it simply here, I usually come up with three goals when I'm making a level: a short-distance, middle-distance, and long-distance goal.

For example, going to see Cinderella Castle in Disneyland would, for us, be a long-distance goal; if it was a game, we'd need to keep reminding the player where he's going if we actually want him to remember it.

A more short-distance goal, meanwhile, would be if you're in a baseball game; your goal is to get on base, and there are any number of simple, linear ways to achieve that goal. An example of a middle-distance goal would be if you run into a bridge in the forest that you can't gain access to -- something I do a lot in games. Maybe you have to do a sequence of jumps to reach it, but it's visible, at least.

It's a constant cycle of "fear" and "relief". If you're in an enclosed area, then completing a middle-distance goal to escape it makes you relieved; it makes you think "Oh, that's how I get out of there!" I'm always thinking about that kind of thing.

Short, middle, and long distance -- how do you manage those goals? What is the critical difference between short and long distance?

HY: It depends on the player's moving speed. For normal gamers, these short-distance goals would be around 30 seconds each.

How do you judge when the player should feel he's accomplished a small goal -- or one type of goal, and now another type? What kind of feedback should the player receive in order to know "I've accomplished a bigger goal now"?

HY: The important thing here is that the player always feels like he's in control of his own fate -- that he's got a full understanding of the world around him and what's going on. That has to be a constant process.

And how can you do that in an open-world environment? In Sonic games, it was 2D and you can see everything around you, but in an open world, there's so much to interact with. How can you have the player feel that way?

HY: Well, for example, if there's a house in an otherwise completely empty area, then the player will probably try to go in, since there's nothing else to check out. If you're in a shooter and the enemy is shooting at you, then you know that you have to avoid the bullets and come up with countermeasures.

No matter what the environment, if something special is nearby -- whether it's hostile or not -- it will grab the player's interest. There are lots of ways this can manifest itself.

What about when players have multiple goals? How do you rank which goal is most important for them? Like, there's a guy shooting at you over here, but over there, there's a treasure. Do I get the guy, do I go for the treasure? How do I emphasize to the player that he should get the guy first?

HY: That's sorting in action, and that's the sort of gameplay I always try to have going. It's the player's responsibility to figure out how to best sort through his situation -- whether the threat is weak enough to merit ignoring it for the time being so you can get the treasure or not.

Is there a particular strategy that you take for that kind of scenario?

HY: Well, like I said before, you can see a middle goal, but there's no obvious way to get there -- you have to jump or cross a gap. The kind of game mechanic is important here. The player always has to think about how to get there. That's the way games are made, really.

It seems like an old way of doing that might be, before you reach the middle goal, you have to find a key so you can get past this gate and then go. But now we have more involved things, like you have to knock down a tree, or something, and you have to beat some enemies first. You could always knock down that tree at any time, but you have a small obstacle in front first. That seems like the more modern type of game design.

HY: Right.

How do you deal with that kind of situation?

HY: Hmm... like, the first person shooter approach to that sort of thing?

Even Resident Evil still does that sort of thing -- you need the red key for the red door...

HY: Yeah, that sort of thing is too obvious. (laughs)

What would your solution to that be?

HY: Well, it's plain that the "red key" approach doesn't really match up with the visual standard game worlds are made with these days, so I guess you need to have a more natural approach. A lot depends on the type of game.

For example, in a game where you can climb freely, you create areas where it's possible to do that, or you make a spot that lets you traverse your way elsewhere if you double-jump or something. Or you give the player tools to use if it's that type of game, like in Zelda.

In an open world like Grand Theft Auto, the player can go anywhere at any time, and do anything. Many American games are moving toward that, and so you must also have to be thinking that way somehow. In that kind of scenario, what do you think is important -- do you think it's important to keep a player on the designer's goal, or can they be doing whatever goal they may set for themselves?

HY: That really depends on the game. Even in GTA, you're still always reminded of the really important things that you should do. If you're lazing out on a mission, you'll get a call asking you what's up. That's the way the game motivates you to continue.

Really, "freedom" is not what you get in a game. In Second Life, they say you can do anything you want, but really, there's nothing to do there! That's not a game. In a game, the designer is a "game master", and he has to be thinking about you.

Do you think of yourself as kind of the "master" of that experience?

HY: I definitely think so. I think it's important you give the player an engaging and interesting experience.

Do you think it's possible to give the player too many goals, all at once? Like, again in GTA, or in the open part of Uncharted, do you think it's possible to have too many things the player could do, so they get overwhelmed?

HY: Hmmm, that's difficult... Well, you have individual goals, like in GTA where you're trying to kill X enemies within one minute, but I don't think that is the goal -- the real goal of the game.

There's a difference between making a game and making a virtual world and putting it in a package. It's the job of the game master to take that world and give you the motivation to move through it. If you don't, then that won't leave the player satisfied.

If you're just trying to keep the player playing as long as possible, then that's like an online game, where the focus is much more on communication -- "Hey, how are you, let's go kill that enemy," you know. That communication aspect is part of the game, yes, but...

That kind of scenario seems to allow a group of people to determine the goal, to an extent. That's an interesting way of thinking about it. From my perspective, sometimes when I start up a game, it says "You can do this, and this, and you can customize your character, and then you change his color, name him, then you set up your party...", and it's just too much. They give me too many options, and I don't want to play.

HY: Yeah, naturally.

And how do you avoid that? How do you decide what's the most important for the player at a certain time?

HY: Mmm... For example, you could make the setup process the same every time and have it so you can start it right away; I like games like that. Then, after that, you could go buy your own equipment to customize if you like, or make your own designs.

People who want to do that could, and those who don't aren't forced to. Keep the basic experience simple, and allow players to explore it at their pace.

Yeah, sometimes the problem with optional things like that is that if the hardcore player will want to try it, but then they'll burn themselves out because it's too much.

HY: I definitely understand that. When you begin the game, you're on a high; it's like "Aaah! What am I going to do?"

And this seems to happen a lot in MMOs, for example.

HY: Exactly.

You start at level one and everyone else is at level 60 or 70.

HY: Yeah, and then you just say "Forget it" at the start. (laughs)

So in your opinion, how has design changed from 2D into 3D?

HY: I think it's mainly in the camera -- its positioning. That can change everything. If you place the camera to the side, then it's a "2D" game, but in a 3D game, it's all in how well you can express the world to the player, how clearly you can show elements and obstacles. There are lots of approaches to solving that problem, so there are lots more possibilities to explore.

What was the first 3D game that you worked on?

HY: Sonic R, I think.

Was it difficult to make the transition -- to decide what was important for 3D back at that time?

HY: I definitely spent a lot of time thinking about the camera -- whether it was too close or too far. If it's too far, then you'd start to have polygon issues, but if I put the camera down lower, then you couldn't see far enough ahead. So I experimented with raising the camera when there weren't too many polygons on screen, and so forth. It was a major headache for me.

So field of vision was a big problem. And in terms of considering what a player could do in a 3D world, was that a difference for you? Did it require extra thought?

HY: Well, even when I was making 2D games, I always think in terms of a 3D world. It was the same back in the Sonic days. For example, you're never going to take a loop in Sonic from the other side, so I never really considered that when constructing the course maps.

That's interesting to hear. I guess that would make sense, why it wasn't a difficult transition. Did you draw your designs in 3D style at that time as well?

HY: Yes. There was the corkscrew in Sonic 2, for example, right? I had to think all that out in 3D. Also in Sonic 2, you had these pipe passages where you would be thrown around all over the place until you came out somewhere else; I had to work out all the layers involved in that layout.

It's funny how quickly you drew him again. It seemed very natural, like "Sonic? Okay!"

HY: (laughs) Lemme draw one more.

Ahh, that's great. So...this may be a question you answered long ago, but when Sonic was created, Sega, as I understand, wanted a mascot. So how were the three of you chosen, or were you just coming up with this yourselves? Like, Ohshima, Naka and yourself.

HY: Like, how we wound up choosing between an armadillo and a hedgehog?

Did they tell you three to do it, or did they say "OK, everybody at Sega, come up with an idea"?

HY: No, it was just us three, and the mission statement was just "You guys have to make a mascot for Sega."

How many design iterations and ideas did you go through before you came up with this?

HY: Well, in the very beginning, the project staff consisted entirely of Naka and Ohshima, back before I joined them. The main thing Naka had thought up at that time was a game engine that scrolled really, really fast -- the problem after that was to figure out what kind of game we could make with that.

We didn't have any game at that time, so we had to think about that first. I thought it'd be enough to have a game where you ran really fast, but we couldn't get anything to work. Naka was really adamant about the idea that the game should be playable with one button, since Mario needed two -- jump, and run or attack.

My response to that was that if you have only one button, then all you can do is jump, so we need to find some way the player can attack at the same time. So our character needed some way to deal damage just by jumping, and from there, we came up with the idea that he should roll himself up into a ball while in the air. I think that was how we first started off.

Did Sega want the mascot to be specifically popular in the US?

HY: Yes, that's true.

Is that why he's red, white and blue?

HY: Well, he's blue because that's the color of Sega [the Sega logo].

Oh! But then, the red and white shoes...

HY: Well, that...hmm, that I'm not sure about; you may want to ask Ohshima about that.

Okay. Someday, I'd love to.

HY: Maybe there was that sort of meaning, since we definitely were trying to make this popular in America.

I also heard that originally, when Sonic would get hit, the rings would not come out. Is that true? And then that was later implemented to make it more interesting.

HY: Well, I think the way rings shot out of you when you got hit was there from the beginning. But the Genesis's power means that you can only show so many rings at once, so we experimented a lot at first with having the rings flash and not overlap with each other and so on.

HY: Well, I think the way rings shot out of you when you got hit was there from the beginning. But the Genesis's power means that you can only show so many rings at once, so we experimented a lot at first with having the rings flash and not overlap with each other and so on.

After a while, though, we realized that having a ton of rings onscreen would be a selling point -- it'd show how cool the Genesis was, and it was visually interesting. So we tried our hardest to make that happen.

Actually, what games did you work on before Sonic? I actually don't know.

HY: Before Sonic, I worked on things like the arcade version of Altered Beast. After that, I worked on downloadable games [for the Mega Drive's Game Toshokan system in Japan] with Mark Cerny.

Really? Which one?

HY: Pyramid Magic and so on.

And then you worked with him again on Sonic 2?

HY: Yeah. He was the president of STI [Sega Technical Institute], so he wasn't involved with the day-to-day process; he was more of a producer.

I was about to ask you all the rest of the games you worked on, but I don't know if that's too much... Oh, you have them?

HY: These are some of my old game designs. Boy, I have a lot.

Oh! Why do you have that here?

HY: (laughs) These are the games I was working on apart from Sonic the Hedgehog. Some of these didn't come out. There was Sonic & Knuckles...I worked on Sonic 1, 2, and 3, then I went to London for Sonic R with Sega Europe.

After that, I got some money from Sega of Japan to work on games and ride technology projects for Disney, and after that, Sega had bought Visual Concepts around that time, though they're called 2K now, so I worked with them on Floigan Bros. for the Dreamcast for a bit. After that, Sega dropped out of hardware, so I moved on to Naughty Dog and worked on Jak 2, Jak 3, Jak X, and then Uncharted.

What made you choose Naughty Dog at the time?

HY: That's because I thought the first Jak & Daxter was just an incredible project. Really, really impressed by it. I was amazed by what they were doing with the PS2. That, and Mark Cerny invited me over, which was also big.

But he doesn't work there now.

HY: Well, he works for Sony; I think he's doing a fair amount of things for the PS3 right now.

What kind of game do you want to make in the future?

HY: Well, a character game. In the end, I definitely want to make a character game. There are lots of first-person games these days; it's almost the main genre in a way. I don't think I need to make any more of them, because somebody else can do that.

Do you think that character games are still possible? Because there haven't been very many good ones, except for...there's still Ratchet & Clank, there's still Jak & Daxter.

HY: Oh, definitely.

But other than these two, not really... Of course, Super Mario; I'm not really into it myself, but...

HY: Well, I think that's the perfect chance for me, then. There's no competition, so if you make a character game for, say, the next generation, I think it'll have a seriously good chance. I think, anyway.

I hope that's the case, because too many games are kind of forgetting how to be fun. They're kind of challenging, or competitive, but that sense of real happiness and fun is not there.

HY: Yeah. For example, the piñata game [Viva Piñata] on the Xbox. I think that's a really neat game -- the game itself is good, of course, but I really loved the character concepts. If we had more titles like that, it'd be a good thing for gamers and for the industry, too, I think.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like