Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

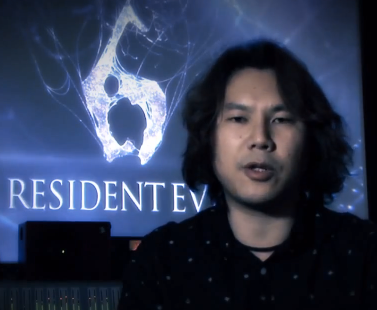

What goes into making a game like Resident Evil 6? In this interview, executive producer Hiroyuki Kobayashi, producer Yoshiaki Hirabayashi, and director Eiichiro Sasaki discuss this task at length, describing how the game was developed using an entirely new production methodology for the studio.

What goes into making a game like Resident Evil 6? Think about it. The game stands at the absolute head of its publisher's lineup, and also has to draw on 16 years of accumulated franchise history while still surprising fans. It also has to outdo all previous installments in the franchise -- and match up to the current generation state of the art while being built in a reasonable time frame.

Executive producer Hiroyuki Kobayashi has called the game "by far, the largest-scale production Capcom has ever embarked on". How do these developers deal with such a massive undertaking?

How would you do it? In this interview Kobayashi, producer Yoshiaki Hirabayashi, and director Eiichiro Sasaki discuss this task at length, describing how the game was developed using an entirely new production methodology for the studio, and how that lead to better results for the game and the satisfaction of its 150-member strong team of internal developers, which swells to a massive 600-plus when you include external contractors and outsourcing.

When you sit down to do a sequel to a franchise like this, what is the first thing that you think -- the first thing you have to think, with so much history, and so much pressure as well?

Hiroyuki Kobayashi: I think, especially with numbered iterations in the Resident Evil franchise, you have to think, "What are we going to do to surpass what we did with the last iteration of the game?" So with 6, I think the first thing we all thought of was how are we going to surpass what we did the last time out.

Hiroyuki Kobayashi

What defines "surpass"?

Eiichiro Sasaki: I think, for me, "surpass" means to create a new experience. So you want to create something new, something that you didn't do in Resident Evils 1 through 5.

And when we're talking about "experiences" -- is that a gameplay experience, is that a story experience, or is it a holistic experience?

ES: Definitely a holistic experience.

How much pre-production and pre-planning goes into a game like this, if you want to get a holistically new experience? How much work goes into defining that, before you even set foot on developing it?

ES: Pre-production on this game started in July 2009.

HK: Yeah, I think it takes at least half a year for something like that.

Yoshiaki Hirabayashi: For just half a year, we gathered everyone's input and feedback before really starting the game.

What kind of size team does a game like this have?

YH: Just internally alone, we had about or over 150 members working on the game -- internally. But when you consider external partners and all outsourced elements, and things like that, there were over 600 people involved in the making of this game.

Yoshiaki Hirabayashi

Managing that process must be so complicated. You can't just have one person managing all of that; just the level of which you manage that is just so complicated.

ES: Well, we have everything broken down into different sections. So we have, like, the game designers, the environment designers, the artists, and each of those groups has its own, you would say, director controlling that. But then within the team, itself everything is comprised of different units, and each of these units is like its own game development company. So they're working on portions of the game individually.

Eiichiro Sasaki

Now usually, what you think of when you think of something like that is, you have a group of, say, artists, programmers, and designers, and you say, "Okay, you guys are working on zombie movement," and then, "You guys are working on the controls for the player characters", and things like that, and it's really a piecemeal process.

Well, we didn't do it that way. Our units were in charge of actual stages of the game, and so they had to create everything for that section of the game. So it's as if each unit was its own company, creating its own individual product, and so then we had to bring that together. And so you had all these separate units working on their own things, and then it becomes much easier to manage them overall.

Is that a new process within Capcom for this game?

ES: Yeah, that's definitely a new process for us.

Why did you decide to do it that way?

ES: There are a lot of goals when making a game like this, and for us, originally, our goals were, we want to make it quick, cheap, but good. And so that's your guiding mantra -- but then, we're trying to surpass what we did with RE5.

So it can't just be fast and cheap quality; you have to try and maintain a high level of quality in a game you're producing. So by breaking it down like this, we're able to localize our efforts and maintain high quality, I think.

Were you able to create something cohesive that came together in the end with that process?

ES: I think that yes, we did. Because we had a vision from the beginning, and I told people what we wanted -- "these are the goals, this is what we're trying to achieve" -- and then we broke them down in every unit, and went to work individually. But at the end of the day, they were still working towards the same goals that I had laid out from the beginning, and I don't think people deviated too much from what my vision was.

How do you communicate that vision, and how do you keep people on track?

ES: Well, from the outset, it would just be completely impossible for me to communicate with 150 people on a daily basis. But that's, as I said, why we have those individual units. And we had about, say, 10 directors -- one for each unit -- and I would have constant meetings with them, and I would explain to them what I wanted, and what my goals were. And they would translate what I was trying to say into stuff that each of the units could understand, and it was about just constantly refining that process.

Was stuff feeding back up to you? And is there room, on a project of this scale, to take into consideration what people on the ground level are saying and learning -- running into problems, or finding new solutions that you could then transfer over from team to team?

ES: I guess I should say that at Capcom we're all on the same floor for development, so it's not like we're all spread out and it's hard to communicate.

YH: And there's no cubicles or partitions like blocking communication, so we're very close together. So we can just shout across the room at each other and whatnot. The lines of communication are very open on that floor.

Does Capcom have a culture where people can say, "Hey, wait a minute. This isn't working," or "Hey, wait a minute. We've got to think about this in a different way"? Can they say that to people who are above them in the hierarchy?

ES: I think it's just something with human relationships. My door's always open for people to come and express their opinion to me, but sometimes there's things that are difficult to express to another person, and that's just life, I would say. For example, I could theoretically just go talk to the president of Capcom if I had a problem, but I probably wouldn't do that. I would probably go through someone, an intermediary, to convey what I wanted to say to him, and I think it's the same way throughout the company.

And like I said, 150 people on the project. That's a lot of people's opinions to try and incorporate into the project. So that's why we had to have these units broken up. And then we have core members that are always contributing and giving us feedback, and you try and incorporate those opinions into the game, and make sure you're always improving it.

But then you consider so many people working on the game, if you break them into disciplinary units, and they're working on an isolated part of the game – so it's like they're making just one part of the product – people get bored with just their one part and they don't feel like they're contributing to the whole. So because we broke everyone down into these units where they're contributing to a small whole, there's more satisfaction, more motivation for them to work on that part, and then we bring all of it together.

How did you determine what direction you wanted to go with the gameplay? Obviously, Resident Evil's been moving away from horror and more towards action. How do you determine that kind of thing, and what goes into determining that?

YH: One of the goals with this game is that I wanted an ensemble cast where I could have all these human relationships, and focus on how horror is shown differently depending on the point of view of the character. As you know, we have four campaigns in this game, and I think that allows us to show horror in different lights.

With Leon, we have that gothic, classic Resident Evil-style horror; with Chris, it's more like a horror of the battlefield with his group. With Jake's campaign, he's being chased by this creature, and being stalked, and with Ada it's more of a very classic Resident Evil-style single player experience as well.

And of course you add to that with her mysterious spy persona, and whatnot, and it's a completely different style of horror. And then you want to bring all four of these horror experiences together under the umbrella of RE6.

Why do you think horror games and action games are mutually exclusive?

It's usually a sense of being empowered, for one thing; it's hard to feel real fear if you have the power to fight back.

YH: That's the very same issue that we, on the dev side, were wrestling with when making this game. And so our answer to that is, okay, you don't make the player feel completely powerful. And one of the ways you do that is you can give them a powerful weapon, but what if you limit the amount of ammo they have? So now it becomes a choice of when you use this ammo.

For us, the campaign in Resident Evil 6 is a very important part of the game -- the most important part of the game -- and so someone might start to play the game, and they would play a number of stages all in a row. But then they have to consider, "Should I conserve my ammo? Should I use it now? Should I save it for later?" That kind of tension that you give to the player -- by not letting them know when they can use these weapons -- I think maintains the horror elements in the game. So while there's still action, I don't think we're losing the horror, just because we keep action in the game.

One of the ways that I think the horror genre works well is when you have a personal connection to the protagonist. In this game, you have multiple protagonists. Does that affect the way that the player relates to them? Does it affect the story, in the way you portray it?

ES: I think we've been very careful in designing it in a way that won't impact the game negatively. For example, we're using an ensemble cast, as I've said, but we're not just throwing random characters together just for the sake of it; they all have a reason for being there.

So when you play Leon's campaign, it's not just about Leon. Sure, you play his campaign and, start to finish, you find out what's going on with Leon's story, but there's more to it than just that. By playing the other campaigns, you'll learn more about Leon's story as well; it'll give you another perspective.

So when you're playing with Leon, you get the full story, but you may be at a loss to understand certain motivations for, say, why Leon did something, or what was happening with Helena, and why she was doing this. And we're hoping to create that interest in that people want to play the other campaigns, and by playing the other campaigns they get the fuller story. And hopefully that brings more of a resonance with what happens to Leon, and you feel more attached to the character as a result of that.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like