Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A series about what and how I teach. In this lesson: designing meaningful choices and an exercise in fixing a "broken" game.

How I Teach Game Design.

Lesson 2: Broken games and meaningful play

designing meaningful choices + an exercise in fixing a “broken” game

The Game Modification assignment

In the last post of this series, I discussed some of the principles of iteration. The Tic-Tac-Toe exercise is a good way to get a beginning sense of the game design process, but iterative design really kicks in only when students get take-home assignments that they need to evolve over a longer period of time.

The assignment below is the first take-home project I give to students. It’s a 1-week project, which means the week after I assign it, students bring their finished games into class to share with everyone else.

RSP: Crossfire! by Craig Donahue, Andrew Jajja, Lyle Sterne, John Xiao

BROKEN GAME MODIFICATION

1-week assignment

Summary

Modify a “broken game” into a more meaningful play experience

Goals

• practice in iterating a game design

• understanding what makes a game “broken”

• analyzing the core mechanic and designing meaningful play

Preparation

In small groups, students are given a “broken game” to play. The games I have used in the past include:

War

the traditional card game

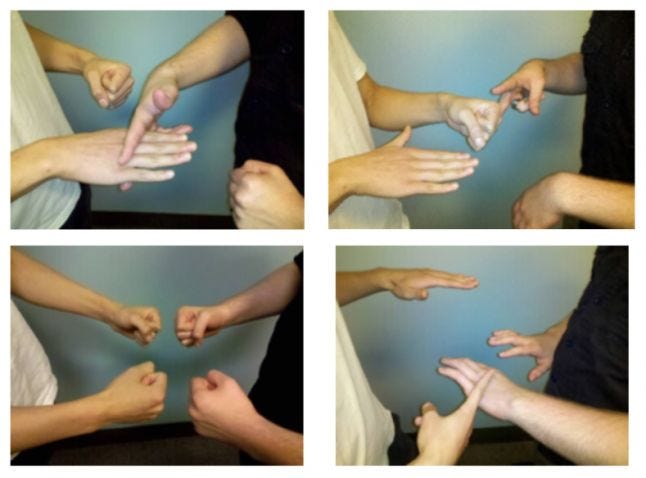

Rock-Paper-Scissors

the classic hand gesture folk game

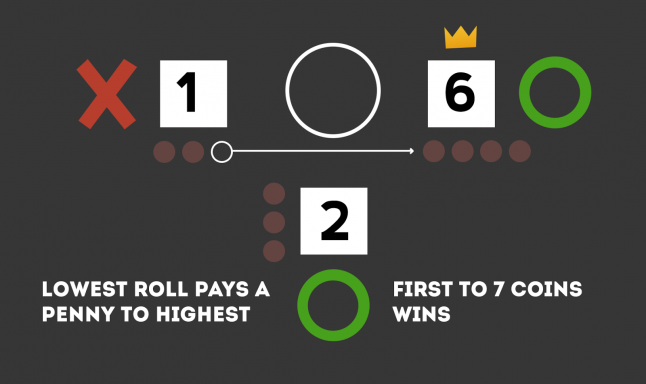

The Dice Game

roll a die, add the number to your total, and pass it to your left -

the first player to 20 points wins

The Number Guessing Game

think of a number from 1 to 100 - someone else tries to guess it -

if they guess wrong, they lose

Matching Pennies

two players each have a penny, and choose either heads or tails

both players reveal their pennies simultaneously - if they match,

player A wins – otherwise, player B wins

Modify!

Students analyze their game to figure out what about it is “broken.” Then they design a variation of the game that attempts to fix the broken aspects of the design they identified.

How broken is broken? The games that are the starting point for this assignment vary in just how broken they are. War and Rock-Paper-Scissors can actually be fun games to play, even though they do have the problem of being more or less random. The other three games are much worse: they’re mind-numbingly dull to play. But all five of the games lack a sense of meaningful choice for players. And this should be the focus as the games are redesigned.

This assignment is similar to the Tic-Tac-Toe exercise from the last post in this series, except that there is a full week to complete it. In fact, the Tic-Tac-Toe exercise is very much a warm-up for this first take-home assignment.

How far is too far? In a game modification exercise, the question arises: at what point has a modified game strayed so far away from the original game that it is in fact a completely new and different design? I want the students making variations, not completely new games. My rule of thumb is that an outside observer, who knew nothing about the assignment, should be able to recognize the new design as a variation of the original. If someone couldn’t reasonably see that Hamsters-Cheese-Chocolate isn’t a modification of Rock-Paper-Scissors, then the design has strayed too far away from the original. However, the most important thing is to make a game that provides players with meaningful choice – I try not to split hairs on whether a design has strayed too far away from the original, and generally give students the benefit of the doubt.

What do they turn in? As outlined in the syllabus, each time students complete an assignment, they turn in a standard set of materials:

• the actual game materials (cards, board, pieces, etc)

• a title page that includes the names of the designers as well as an “abstract”

that gives an overview description of the game in a few sentences

• a set of complete and edited game rules

• photos of the game being played

• a design process statement – a 1-page description of the group’s process

in getting to the final design

• peer reviews

Some of these items, like the rules and list of materials, are just a basic part of making a game. Others, like the abstract and photos, are documentation for the NYU Game Center archive, where we store student projects. The design process statement plays a different role – it gives me insight into how the design evolved, providing context to help evaluate the finished game.

The peer reviews are a chance for students to grade each others’ performance as collaborators. Peer reviews are a more complicated matter and I’ll be addressing them in detail in a future post. In any case, I often don’t have students complete peer reviews on their first assignment, so that they are a little less self-conscious as they try and wrap their heads this “game design” thing for the first time.

Ugly but clear. My classes are not visual design classes, and I so do not expect anyone to express themselves with detailed illustrations, expert typography, or polished visual design. In general, I would rather that students spent their time iterating on the rules of their game rather than the art direction. For a prototype, ugly is beautiful! That said, the dividing line between visual design and game design is blurry, and designers do need to create materials that are visually clear and have good play ergonomics.

For example, in the case of a card game, I will expect that thought has been put into the card layout. Is the most important information clearly visible? When the cards are being held in hand, can players see everything they need to see? I don’t mind unpolished prototype materials, but game designers do need to be able to think visually and produce clear and usable game prototypes. This is an important skill not just for a student in a class, but for any working designer.

from the rules for Veto Dice by Winnie Song, Jeremy White, Zack Zhang

The Core Mechanic and Meaningful play

The Game Modification assignment raises a number of fundamental issues about how games become meaningful for players. In preparation for this assignment – and during the critique of the projects that it produces – I like to talk about core mechanics and meaningful play. Below are the kinds of issues I bring up with the class.

What are players actually doing? Designing a game is designing an activity – something that fills up the time your players spend for seconds, minutes, hours, days, even years. While some may think about games in terms of their visual aesthetics or narrative content, the fact that a game is a dynamic system with which players interact defines what is unique about games as an expressive form. Game designers have to create an activity with which players engage, from moment to moment, over time. A question designers need to ask themselves is: what are your players actually doing to fill their time as they play?

A repeated activity. For most games, the activity of play boils down to a fairly repetitive activity or set of activities – the core mechanics of a game. The core mechanic of the sport of Sculling is rowing a boat. The core mechanics of Poker are drawing cards, playing cards, and betting. The core mechanic of Starcraft is using the mouse and keyboard to issue commands to your units. When I worked at R/GA in the 90s and real-time strategy games like Dune II, Warcraft, and Command & Conquer were just emerging, we used to call them “Photoshop games.” The graphic designers who were fluent with Photoshop’s command-key shift-alt-clicking had lots of practice in the core mechanics of RTS games and dominated the office tournaments.

Making activity meaningful. An important part of game design is to make the core mechanic of your particular game meaningful. Whether it is reading text and clicking on links, moving through a 3D space, or moving pawns on a gameboard grid – how can you make that activity meaningful? Giving a player meaningful choice means providing a context for players to know what their choices are, to be able to choose one option out of several, and to understand how their choice has affected the state of the game.

Action -> Outcome. As players play a game, they make many small decisions – whether the decisions are made in real-time, as in a sport or action videogame, or whether they are happening discretely, as in a strategy game where play happens in turns. Each action a player takes has some kind of outcome in the game. These action/outcome moments are the molecules of meaningful play. Gameplay is the moment-to-moment experience of these small pearls of decisions, strung together to extend across longer periods of play.

Designing a context of meaning. A game design should provide a context in which every player choice is meaningful. If a Chess set is sitting on a coffee table as merely a conversation piece, moving one of the pieces on the grid doesn’t really change that much. But if a game is in session, it suddenly matters very much exactly which piece you move, and when, and where. What does an action mean in the game – how does its outcome ramify over time? A player’s action becomes meaningful in the context of the game. The game is the context that helps to provide meaning for the action.

Breakdowns in meaning. Meaningful play is often most evident when it doesn’t work. You have a hand of cards and it seems like it doesn’t matter which one you play; you raise taxes on your virtual city and you never really understand the outcome of that choice; your character died and you don’t know why – all of these moments represent breakdowns when a game fails to provide meaningful play.

A space of possibility. When it does work, meaningful play gives players expansive spaces of possibility – sets of choices and outcomes that represent interesting possible ways to play the game. This is what makes players want to try a game again – to see how their choices might play out differently if they attempt new approaches. A game design should give players spaces of possibility that they can explore in their own individual ways.

The Game Modification assignment is a great way to begin exploring all of these key game design issues. Designers must first understand the core mechanic of their “broken game” and why it is failing to provide meaningful play. Then they need to redesign the core mechanic in order to tease out more meaningful play experiences for players. The idea of meaningful choice is so fundamental to game design that in fact every exercise and assignment in my class addresses it in some way or another.

Further reading

Meaningful play is probably the central concept in Rules of Play, the game design textbook I co-authored with Katie Salen. A good place to start reading about it is Chapter 3: Meaningful Play.

---

This series is dedicated to my co-teaching collaborators and other game design instructors who have taught me so much, including Frank Lantz, Katie Salen, Nathalie Pozzi, Naomi Clark, Colleen Macklin, John Sharp, Tracy Fullerton, Jesper Juul, Nick Fortugno, Marc LeBlanc, Stone Librande, and Steve Swink, and the NYU Game Center faculty.

I also want to thank some of the many many teachers that have inspired me throughout my life, including Gilbert Clark, Enid Zimmerman, Weezie Smith, Susan Leites, Gwynn Roberts, Pat Gleeson, Janet Stockhouse, Janice Bizarri, Sensei Robert Hodes, and Sifu Shi Yan Ming.

Special thanks to Frank Lantz, Nathalie Pozzi, John Sharp, and Gamasutra editor Christian Nutt for their input on this essay series.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like