Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In Other Waters creator Gareth Damian Martin discusses how mechanics and design shift when translating a video game to the pen and paper world of tabletop role-playing games.

In 2022, you can see the DNA of Dungeons & Dragons peppered throughout this year's most anticipated releases. Tabletop role-playing games and video games are inextricably linked, but video game RPGs can feel repetitive, many still relying on the same tired interpretations of D&D mechanics. At the same time, the independent tabletop scene has been pushing boundaries of creativity and storytelling with modern tabletop games like Blades in the Dark and T.I.M.E. Stories.

In recent years Gareth Damian Martin, game designer and founder of the zine Heterotopias, has fallen headfirst into these types of tabletop games. Both of their current projects are blending ideas from one form of gaming into the other. The pressing focus is turning their 2020 game In Other Waters into a module for the sci-fi horror TTRPG Mothership as In Other Waters: Tidebreak. Both the original and the module are crowd-funded projects.

The Kickstarter for In Other Waters: Tidebreak raised over $69,000, quite nearly twice what the campaign for the video game earned. The biggest difference for Damian Martin this time? They aren’t doing it alone. The project is a collaboration with Lone Archivist, an experienced TTRPG module designer with a particular interest in the sci-fi genre.

“Andrew [Lone Archivist] actually approached me asking if I was interested in collaborating on something, maybe to do with In Other Waters,” Damian Martin said. “It just so happened that I was in the final stages of development and since then I’ve been really into tabletop role playing games. I had noticed In Other Waters had been quite popular with people in the tabletop scene because of its reliance on maps and text and the way it asks you to fill in the gaps.”

In video game form, In Other Waters uses a stylish overlay to navigate and explore the murky depths.

The idea that In Other Waters' jump to the Mothership system was a seamless transition from video to tabletop game is a stretch. Game development is anything but seamless. However, more often than not elements of the original game’s design philosophy lent themselves well to the new format.

“[In the video game] an important part of the design philosophy is [that] I wanted players to plan dives and then go on dives. That pattern and structure can be quite a natural fit for a tabletop game. The idea of ‘here you have this map in front of you, where are you going to go? How are you going to study this world?’ That was a key way of translating it.”

The mechanics of In Other Waters encourage players to explore an alien ocean planet via unique systems and minimalistic presentation. According to Damian Martin, the intention was to get players to study the world and its lifeforms with care and attention. Studying the ocean’s creatures was as important to the game’s overall focus as the narrative journey of the player character, xenobiolgist Ellery.

In the video game, Ellery’s story got a definitive ending, but Damian Martin still wanted players to tell their own stories. As a result, Tidebreak takes place directly after the events of In Other Waters. It is in many ways a direct sequel, but at the same time it is more of a toolbox for building a sequel. As they elegantly put it, Tidebreak is not a sequel but “a moment when a sequel could happen.”

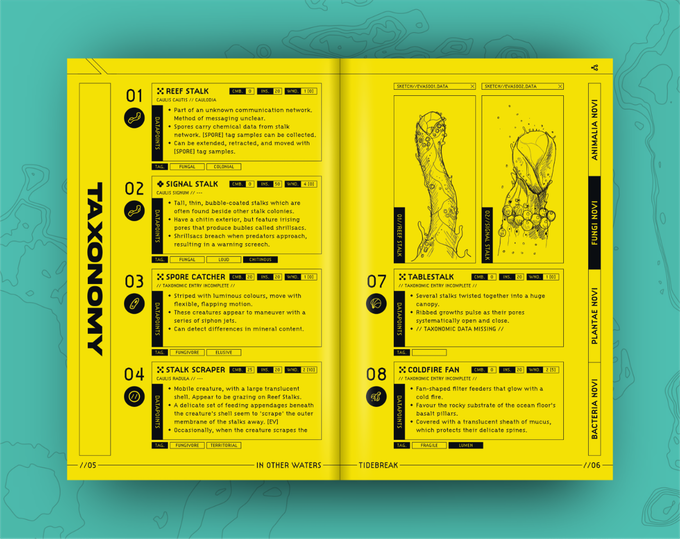

As a narrative and aesthetic continuation of In Other Waters, a large consideration going into Tidebreak was graphic design. As a trained graphic designer themself, Damian Martin knew this would be a key part of communicating that Tidebreak takes place in the same world. The identity of the game is contained in the colors and graphic identity, as well as the sketches and creature designs that litter the rulebook.

The video game included a taxonomy of creatures that acted as pockets of lore that fleshed out the world. This type of floral prose has no place in tabletop gaming, but Damian Martin found a way to incorporate the idea of a taxonomy into Tidebreak that allowed them to revisit ideas from the early prototyping stages of In Other Waters. This became Tidebreak’s tag system, which is how the game ascribes traits to its creatures. The creatures are not enemies, so they don’t have resistances and weaknesses like in D&D or Shadowrun. Instead, these tags inform players about the creature’s ecosystem; where they live, what they eat, how they protect themselves from predators, etc.

Tidebreak's taxonomy, shown as a work-in-progress spread.

“One of the things I wanted to do early on in the prototyping phases was [have] real creature behaviors, but I realized the structure of the game and scale of the compass is too small to communicate that,” Damian Martin said. “With the tabletop game you have a higher chance of emergent behavior. That’s the idea behind the tag system. To not set an explicit set of behaviors, more to give a series of prompts to understand if for example two creatures just showed up in the same place, what would happen? You can compare the tags and immediately be like ‘this creature wants to eat this creature’ or ‘they are both competing for the same food.’ That type of thing is really hard to do in a video game.”

These types of emergent choices are part of what makes Mothership an ideal choice for Tidebreak. The TTRPG’s framework allowed Damian Martin and Lone Archivist to make a module that encourages players and Wardens (Mothership’s equivalent to D&D's Dungeon Master or a Game Master) to be creative and take risks. Each gameplay session begins with the group taking on a contract. Perhaps you’ve been hired by a corporation or a collector to find a rare specimen, and that’s used as a framing device for the adventure both narratively and mechanically. This system also allows Tidebreak to be worked into the rotation for Mothership players who already have an established group of characters. But more so than many tabletop modules, Tidebreak is focused on giving Wardens the tools to set a scene and tell a story.

“I’ve given Wardens materials to feed the player's curiosity and to respond to them. That’s not something all modules have,” Damian Martin said. “We have a mechanic where you can study the creatures and reveal data points that the Warden can give to players as a reward. Those data points are used as currency in the game as well.”

The focus on making Tidebreak a tool for emergent storytelling became clearer when Damian Martin revealed how much work was put into making the game fun for solo play. Inspired by solo RPGs like Apothecaria and Thousand Year Vampire, the mode adds a journaling element for players approaching Tidebreak on their own. These games give solo players prompts to respond to, allowing them to write down their adventure as opposed to having a GM narrate it. This format is a natural fit for the world because Ellery’s journals in In Other Waters are a key narrative tool and insight into her mind.

The question is how are your tools going to dictate their experience?

For Damian Martin, the biggest difference between designing a video game and a TTRPG module is control; specifically, letting go of it in order to let players create their own experiences.

“It’s kind of scary for game designers [to lose control] but sometimes video games are so overwrought. You have to design every possibility into the system and then make sure that possibility is being communicated to the player. Because if it's not, you might as well cut it.” Damian Martin said. In their experience, designing a TTRPG is exactly the opposite. “You can use breadcrumb trails and tools for people to build things out of. The question is how are your tools going to dictate their experience?”

It’s a question Damian Martin is interested in exploring not just with Tidebreak, but in their next video game Citizen Sleeper, an RPG influenced by modern tabletop design. Both projects (coming later this year) look at the last decade’s best TTRPGs and attempt to harness the creative freedom and expressivity these games allow to players in an age where many games have lost sight of these tenets.

While it's easier to make these decisions in the crowdfunded indie space, it’s still a risk. And if modern triple-A games are anything, it’s risk averse. We can only hope that industry titans like CD Projekt Red and Bethesda decide to look beyond the giants of the tabletop world and find more modern inspiration when creating their next, multi-million dollar role-playing game.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like