Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The one-of-a-kind British programmer behind Gridrunner, Tempest 2000, and Polybius opens up about his life, his relationship, and the future.

Jeff Minter has developed video games almost entirely by himself for his 43-year-and-counting career. But that doesn’t mean the 61-year-old British creator of arcade-inspired classics like Tempest 2000 and truly weird fare like Space Giraffe is an isolationist.

Much the opposite, really. The first 15 years of his career have been laid bare in this week’s Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story, an interactive, game-filled museum for PC and consoles. It’s full of interviews, documentation, prototypes, and more, but it also clarifies why he’s a truly remarkable game maker: his investments in relationships with his players.

Speaking to Minter on the eve of the compilation’s release, the theme of relationships comes up quite a bit, albeit humbly. Minter smirks from his home and farmstead in Wales as he calls himself a creator of “digital narcotics,” though he’s not interested in getting anyone addicted.

He points to a genuine and “euphoric” hope for anyone who plays his unique brand of games: “All I want to do is put goodness into the world,” Minter says. “To make people feel happy, not to make them feel frustrated and get a score, anything like that. You know, in a way, the game almost falls away when you're inside that space, and you’re just doing a thing which feels wonderful.”

A peek at the compilation’s 34 playable games, all made in less than 15 years, makes that quality apparent. Minter’s work often resembles a hallucinogenic interpretation of a stereotypical 1980s arcade–all lights, flashes, bleeps, and bloops, with a color palette comparable to space-themed arcade carpet–only to leave players sucked into approachably frenetic weirdness.

And it’s all indelibly Minter: his ability to distort and twist familiar arcade concepts into new shapes; his care to give players just enough information and explanation to know what they’re in for, while otherwise hiding plenty of surprises; and his propensity to sneak llamas, sheep, and other “beasties” into every game.

Everyone says it, and it’s true: there’s no mistaking a Minter game for anyone else’s.

Yet that’s not Minter’s daily countenance–not even close. His hair is thin, long, and knotty, draped past thick glasses and a giant, expressive smile, like he’s about to pick up a shift delivering organic produce in a van. His choice of sweater is fuzzy and cozy, a perfect match for the spot of tea brought to him during our chat by his longtime partner Ivan “Giles” Zorzin, both domestically and professionally. (“Thank you, sweetie,” is his instant response.) And with a voice that resembles a calmer, more composed Ozzy Osbourne, Minter never misses an opportunity for dry humor, all while being immodest enough to comment about anything–even a failed burp attempt between comments on VR and augmented reality.

In parsing his seemingly contrary traits, you can better view his quest for positive and euphoric experiences as something quiet, transcendental, or even meditative. That’s the tone Minter establishes while talking about the fandom and relationships his games have fostered.

From regularly meeting fans in person (“we’d go to pubs, rent a place out, play games”) to having his livelihood repeatedly saved by well-placed admirers (“various people who were fond of Llamasoft helped push my career on in directions which enabled me to keep going”), Minter has no shortage of life-changing connections under his belt–even while he’s clear that, sure, he enjoys a certain kind of solitude. If someone else can help him with business, engine development, and other tasks, he can be “completely free to sit on my ass and write games all day.”

The crucial thing about Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story is its throughline: Minter’s relationships with his players. Minter admits as much in a subtle, slightly anxious way.

“I hope people don't rush through [the compilation] too much,” Minter says. “I hope they'll give each game a little bit of time. I hope it doesn’t suffer too much from what I call ‘emulator syndrome,’ where you install an emulator on a machine, then you put a bunch of ROMs [digital copies of games] on there, and then you have five minutes on this, five minutes on that, five minutes on that. You don't really get the full flavor of any of them.”

What he means becomes evident after poring through this week’s new compilation, as produced by publisher Digital Eclipse as part of its “Gold Master” series. Like the two other Gold Master entries so far, which focused on Atari’s early era and Jordan Mechner’s seminal Karateka, respectively, L:TJMS shuffles playable games into a museum-like presentation. Where this release differs from other Gold Master compilations is its emphasis on helping new fans linger with each Llamasoft relic a bit longer.

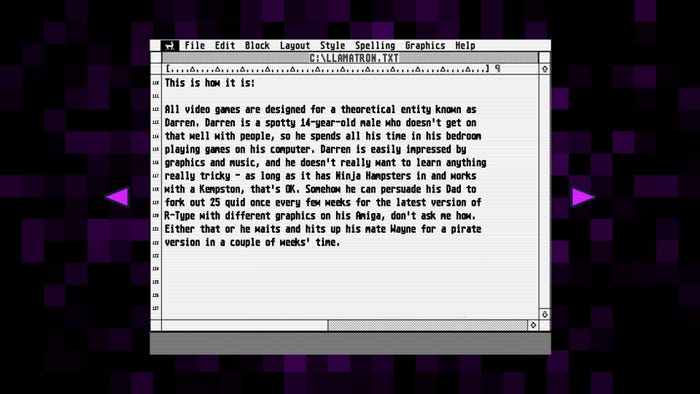

The first sign of this difference comes in the volume of words. As Minter starts to gain confidence and even swagger in his work–with a whopping 17 different games published for British PCs by the end of 1982–his writing ramps up. The compilation includes many issues of his “Nature of the Beast” fan newsletter, which he began distributing in 1984. His games’ instruction manuals (also reprinted in this compilation) soon take on the same unfiltered, conversational format: how games were made, what Minter has been up to, plans for future games, favorite bands, the durability of average computer joysticks, and even his frustrations with an increasingly commercialized “industry” for gaming.

Image via Digital Eclipse/Atari.

Around the same time, words begin to fill his games, as well–which, for the uninitiated, resemble the action-forward likes of Robotron and Defender, not text-filled RPGs. The longer you play any Minter game, the more pop-culture references, manic cries, and silly non sequiturs appear on screen between each zap of a laser. In this way, Minter subliminally connects his worldview with his players the longer they engage with any of his games, even if he describes some of the phrases as “what jetsam is floating about in my brain.”

Minter’s childhood interests landed halfway between English studies and science. “I’ve always liked playing with words,” he says. “If I hadn’t been a programmer, I would have quite enjoyed being a linguist. I enjoy the etymology of words and studying how they fit together.” Some of his earliest memories include both of his British parents taking on “open university courses”--schooling at home, well before that was the 2020s norm–and absorbing what each brought to the house. His mother was a multifaceted worker (nurse, secretary, and more), while his father eventually became an engineer at the UK’s Atomic Weapons Research Establishment. The latter take-home curriculum was a bit more involved and attention-grabbing.

Minter recalls his first time seeing a computer in person. He was nine years old, and his father Patrick had a scheduled block of terminal access at a “time sharing place”--about the only way to publicly access computers in the early ‘70s. After expressing his dismay that this computer didn’t resemble the stuff of sci-fi, able to answer any question about “life, the universe, and everything,” Minter’s father countered: “A computer only knows as much as you tell it.”

Less than a decade later, Minter took that insight to the next level after seeing a fellow college student playing an apparent arcade game on a university terminal. “How’d that game get on that [Commodore] PET?” Minter asked, incredulous that an arcade hit had escaped the dark, neon-lit halls of a typical arcade.

“I typed it in,” the person replied. “Ah,” Minter thought. “That sounds interesting. I’d like to learn to do that.”

This new computer obsession quickly changed his scholastic tune, even if it didn’t immediately convince his parents. “From being not very keen about college, suddenly I was going in early every morning and staying there late every evening,” Minter says. “My parents couldn't quite work out what was going on at first.” They initially described his obsession as a “fad,” though they didn’t obstruct his path to learning more. By the age of 17, Minter had spent his savings on a Spectrum ZX-80 so he could stop fretting about scheduled blocks of computing time at school. By 18, he’d attended a computer convention, handed out homemade copies of his coded-from-scratch games, and gotten a bite from a publisher.

“It was only when I went to a computer show one time with some programs I'd made and came back and told [my parents], I had a deal with some guy who was going to sell my programs,” Minter says. “At that point, maybe their attitude started to turn around a little bit. ‘Yeah, maybe there's some proper work in this for us!’”

Fate had a hand in what came next: a derailment of Minter’s health that forced him to slow down and reassess his life. Bad news: he couldn’t go back to college and pursue computer science. Good news: he was allowed to keep programming. By the time he’d fully recovered in early 1982, Minter had a company name in mind for the games he’d been making: Llamasoft, based on his lifelong interest in the creatures and his proclivity to draw llamas on paper or render them on screens.

And render them he did: whether they guested as helpful creatures in 1982’s Space Zap and Superdeflex, or became outright titular in later titles like Revenge of the Mutant Camels, Sheep in Space, and Metagalactic Llamas Battle at the Edge of Time (yes, really), Minter’s “beasties” became omnipresent. His persistence in adding them is relevant to the computing era Llamasoft was borne from–all crystallized by a certain copyright holder raising its eyebrow at Minter’s cheekily named 1982 game Defenda.

Image via Digital Eclipse/Atari.

“At first, all of us who were interested, we were just copying arcade games,” Minter says. “That’s what you did, until Atari started getting heavy handed about it. Atari being litigious, honestly, was one of the things that pushed me out of a comfort zone of doing copies of things–to try and put more of my own stuff into things. And I’ve always been crazy about animals. So I did this game, Attack of the Mutant Camels, a blatant rip-off of the Parker Bros. Empire Strikes Back game, but with camels instead of mechanical walkers. People loved it! It was distinctive enough. It started to get us noticed.”

Minter suggests that something as simple as a sprite swap–a llama in place of a Lucasfilm icon–was the right idea at the right early-career moment. “It made us stand out a bit from other people who were also making games,” he says. “Once I saw that happening, I had a lot more confidence, then, to open up and entirely do my own thing. It was a blessing, really.”

With the release of his seminal 1983 game Gridrunner, Minter had struck game-design gold–breathing new, frenetic life into the Space Invaders formula–and found himself cracking the PC software sales charts both in the UK and US. This happened after his mother took over Llamasoft’s production and sales reigns, in the wake of a bad publishing deal, which left the Minter family not only in good financial straits but also free to create and sell “experimental” games. “Once we got a bit of a name for ourselves, we kind of guaranteed that whatever we’d put out, people would buy up to an extent,” Minter says.

For the next four or so years, Minter suggests, life at Llamasoft was good. American sales delivered a surprising windfall of cash, which Minter and his family invested for future stability. British sales were strong enough to make Minter a big name in his nation’s microcomputer magazines–so big, in fact, that a negative Zzap!64 review of his 1985 game Mama Llama led to a months-long spat that spilled into its letters column (a conflict so fully chronicled by L:TJMS, it includes a video interview featuring Minter and the original author of that game’s most negative review).

Minter’s willingness to lean into his individuality exploded during this era. Each of his games’ mechanics became all the more complex and fine-tuned, all intending to push home computer gaming to a new threshold where difficulty and score-chasing faded, in favor of dives into synesthesia. This was even more loudly realized by Minter’s advancement into the genre of “lightsynths,” or programs that generated programmatic visuals as timed to a specific meter or rhythm.

The idea for these began in Minter’s childhood bedroom, where he remembered listening to Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon in the dark: “Certain of the tracks on there, like ‘On The Run,’ it was a driving track with a filter sweep going across it. I’d listen and see geometric shapes in my head. Ever since that, ever since I was 11 years old, I thought, ‘I would like to have an instrument one day that would let me externalize these shapes and show them to people.’”

Everything he’d learned in making video games, particularly ones that emulated the Eugene Jarvis school of bombastic explosions, led him to making exactly that kind of interactive software–Psychedelia being his first attempt in 1984, with many others following over the decades.

(Fun fact: If you ever owned an Xbox 360, then you owned Minter’s most advanced lightsynth software released to date, which was built into each console’s music player.)

When asked about psychedelic inspirations, Minter makes a face as if he’s been asked this question a million times: “People assume, when they look at my work, I must have done a lot of hallucinogens. I don't really do hallucinogens! I've just got a naturally psychedelic imagination.” He admits having his third eye opened a bit by “half a pill” at a party in the 1980s, which unlocked an appreciation for electronic dance music that he holds to this very day. (“I was out on the dance floor for fucking five hours,” he says with a laugh. “It was brilliant.”)

The compilation also slams into the reality of a swiftly changing games industry at the end of the 1980s: “There didn’t seem to be a place for somebody like me, who is sitting on his own doing his own thing and publishing his own work,” Minter says.

This week’s L:TJMS touches upon some of his professional misses, particularly his work on the bizarre Konix console, a vaporware project that never officially launched and cost Minter years of time and money. (Digital Eclipse somehow recovered a working build of the game Minter was making for Konix, and it’s now playable for the first time anywhere.)

Others aren’t so fully covered by Digital Eclipse, and Minter freely summarizes them in our call: work-for-hire gigs with Atari UK; an ill-fated move from Wales to Los Angeles (where he at least made the legendary Jaguar hit Tempest 2000); a moment where he nearly took a job with Activision, only to move back to Wales and dump more failed time and energy into programming for the ambitious Nuon set-top box.

Image via Digital Eclipse/Atari.

Nearly 30 years later, Minter still lights up when talking about Nuon’s complicated parallel processing nature and reliance on Assembly language: “It was fantastically complex to code, fantastically satisfying to code, if you were an Assembly nerd like I was,” he says.

Yet these failures belie one risky bet he took that did pay off: a tiptoe into the increasingly relevant shareware market. His first release in the format, Llamatron 2112, included a full, unlocked game and a massive TXT file pleading with fans to send a few quid his way if they liked what they played. They did: “Not only did we get the money back for it, we had people sending more money,” Minter says. “People wrote us hundreds and hundreds of letters, telling us how much they appreciated that we trusted them to pay for the game.”

Llamatron 2112’s shareware launch in early 1991 was the bridge that connected Minter to his eventual, bill-paying jobs with Atari, along with the freedom to make something as mechanically and aesthetically pure as Tempest 2000. “At a time when everything was getting much more commercial, that felt absolutely lovely and pure,” Minter says. “It healed my heart in some ways.”

Years later, as Minter’s life moved into projects and concepts not covered by L:TJMS’s conclusion in roughly 1994, another heart-healing development unfolded: meeting his life partner. And it’s a rare example of Minter having to loudly, if briefly, re-evaluate some of the relationships he’d fostered over the years.

“In the early days, I didn’t really form any kind of attraction, neither straight nor gay, really,” Minter says. “Nothing of this is doing anything for me.” This made a life of programming a more comfortable place to be in his 1970s and 1980s youth: “When the real world feels uncomfortable, coding is a place where everything makes sense. Everything is deterministic. If there’s a problem, just think about it long enough, and you can work it out.”

Minter takes a protracted pause. He’d dated a few times in his younger years, he says with a sigh. “Nothing really worked out. I wasn’t unduly bothered by it. There was so much else going on in my life”--remember, his first two years in the games industry were marked by a whopping 17 different game launches–“and I thought, maybe this is just how it’s going to be. Maybe I’m going to be on my own. I don’t really mind that. But I feel terribly sad about it.”

His tone softens once his partner of over 15 years, Ivan “Giles” Zorzin, figures into the story. “It was a surprise to both of us, really,” Minter says. After meeting online and talking at length about their shared interests, including “the same kind of coding aesthetic,” things happily escalated. “It’s almost like our relationship formed more in the head than in the body, really.”

This explanation emerges maybe 30 minutes after Zorzin has shared a cup of tea and asked me how the weather is where I live. His shadow is occasionally visible in our video chat–maybe to offer occasional reassurance as Minter gets choked up recalling his past, or maybe because they just set their computers up side-by-side as a happy coding couple.

As Minter makes loudly clear, Llamatron would not currently exist without Zorzin as an equal partner, handling all kinds of coding and engine-level challenges. (Zorzin is also responsible for localization work, which comes with its own Minter-ian headaches of translating so many non sequiturs in the text: “He’s like, ‘what the fuck?’” Minter says with a laugh.)

When asked what friction or challenges the couple may have faced, Minter reminds that he had returned to Wales for years by this time, having rejected the game-studio norm of cities like Los Angeles. As such, instead of walking into a potentially unwelcoming studio, he regularly tuned into his YakYak BBS (still online to this day, still archiving posts from as far back as 2002) to confront a brief-but-intense series of public, online challenges from dedicated fans.

“The only hard time I had for it really was not because of the sexuality,” he says. “It was because some people felt that [Giles] was coming in and maybe trying to take advantage of my fame, as such. You know, a very small kind of nerdy fame.” Even this many years later, Minter expends some energy reframing his relationship as a positive to the small percentage of his fans who complained: “[Giles] proved himself. He hit the ground running and he was instrumental. I couldn’t have done the visualizer work on the Xbox 360 without him doing a hell of a lot of backend work.”

But he’s also insistent that the relationship of a game maker with their fans has a clear line that shouldn’t be crossed–and has an emotional impact when it is. “I’m grateful for the fact they like my games,” he says. “But this is my life, and I choose who gets to share it with me, and you don’t have a say in that. I was pissed off with people who were giving us a hard time, and I was pissed off on behalf of Giles because he was getting it in the neck from some of these people. It didn’t last.”

When pressed about parallels his story might have for anyone who’s faced holier-than-thou feedback from customers on social media or Steam forums, Minter continues: “I’ve always interacted with my fans, my audience, whatever, but you can’t let them run your life. That’s madness. Craziness lies that way. You can’t have these people leaning on you, pushing you around. You have to say, I am what I am. If you like it, then yes, I’ll come and talk to you. We can be social. If you don’t like it, then, you know, push off. You can’t change me.”

Should you be moved by Minter’s stories, or compelled by critical adulation about his video games, now is the time to tiptoe through L:TJMS. Play each included game for more than five minutes, then read through each increasingly individualistic instruction manual, or each increasingly vulnerable and honest newsletter, or each increasingly giddy barrage of mid-combat text in his later games.

Feel these words, mechanics, and concepts seep into you as a receiver of Minter’s worldview–the geometric shapes in his pre-teen dark-room mind, transmitted anew as light, sound, and satisfying gameplay. Imagine being so lucky as to live in the 1980s and absorb in real time so many consistently good, weird, and indelible games in every-few-months chunks. That’s the perspective that may answer why in the blazes Minter has been able to make his kind of bizarre, animal-first game-making career work as an indie dev for so long, even in an increasingly frenetic games industry: because he left a mark on fans who helped him stay afloat, again and again.

An early 2000s encounter with a well-placed fan led to Minter being hired to make a boundary-pushing lightsynth software experience for Ubisoft, named Unity; it never launched, but the project paid a few bills (and its concepts and programming were eventually paid forward in 2007’s divisive-but-memorable Llamasoft game Space Giraffe). When Unity fell apart, another studio-owning friend had seen the prototype and forwarded it to a well-placed guy by the name of J Allard, the co-creator of the Xbox, who “was a bit of a fan of my stuff,” Minter learned. Yadda yadda yadda, and Llamasoft was paid to build a visualizer for every single Xbox 360 ever made.

It keeps going: Minter tried pivoting from there in dedicating nearly two years to publishing his own games on the burgeoning iOS App Store, only to see each of his eight games make “about 50 pence.” By the end of that, Minter found himself “exhausted, fucking spirit-crushed.” While at that edge of financial ruin, “a friend of mine put me in touch with Sony” to develop something for the upcoming PlayStation Vita, which bore out the critically acclaimed and commercially successful TxK. “That saved us.” There’s also the time he got cold-called by Trent Reznor to have his 2017 game Polybius featured in a music video, and that visibility, as compared to hiding in plain sight on the App Store, was a financial boon. “The thumbnail on YouTube is an advert for Polybius,” Minter says. “That’s class.”

Llamasoft isn’t done, either. Minter has another entirely new visualizer in the works, designed to work within the cozy confines of virtual reality (he’s already released a few tantalizing games for PSVR and SteamVR), and Zorzin is full steam ahead on an engine refresh to port existing and new games to Meta Quest 3. “I’ve got this idea that before I die, I’ve got to do Space Giraffe 2,” he adds. “It’s got to be done in virtual reality. It’s got to be even more so than Space Giraffe 1, so it’ll probably be even more divisive. But I have to do it.”

His bespectacled eyes continue looking forward to the games he wants to keep making the same way he has for years–on his property in Wales, with breaks to sip tea, visit the pub with his mates, play with the restored arcade machines in his home, and take care of the sheep on his property. But he’s also delighted by L:TJMS as an opportunity to take stock of what he’s built thus far, and the relationships that have gotten him there, even if a few of those are no longer active relationships this many years later.

“It takes you back to various points in your life, and, so…” Minter pauses, swallows, and collects himself. “You have to revisit, you get to think about people who are gone, basically. But I always get a bit emotional when I think back.” A nervous laugh, and then Minter stumbles over some words about the bittersweet truth of reflecting on past successes.

“It made me reflect on what a good time we had, and how fortunate I’ve been in my life to be able to do this,” Minter continues. “What a magic time it was in the early days of the 8-bit era, there! This was wild creativity, before it all formed into this, right, huge industry we now have, that makes tons of money. There was a little period where it was like being present at the Big Bang, you know! Suddenly all this stuff just appeared out of nowhere. A bunch of us that were kids, we found ourselves in the middle of this, blinking in the light, going, ‘what the fuck?’”

This many years later, Minter takes in the entirety of his career with more zen than he applied to his earliest letters and missives from the 1980s. “You have to accept that at some point, not everybody is going to love everything you’ve ever done,” he says.

“If you try to aim for the lowest common denominator to try and include as many people as you can, that's a different kind of motive than what drives me, really. I'm more interested in pursuing the ideas I have, and I don't really care that much if they're wildly successful or not. Oh, it'd be nice if they were. I'm not saying I would turn that down. But I'm not that bothered if they're not. As long as I can carry on doing what I'm doing, I'm happy, you know?”

You May Also Like