Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Sam Barlow, the writer and director of this interactive mystery, title discusses "creating the Dark Souls of watching a bunch of movies."

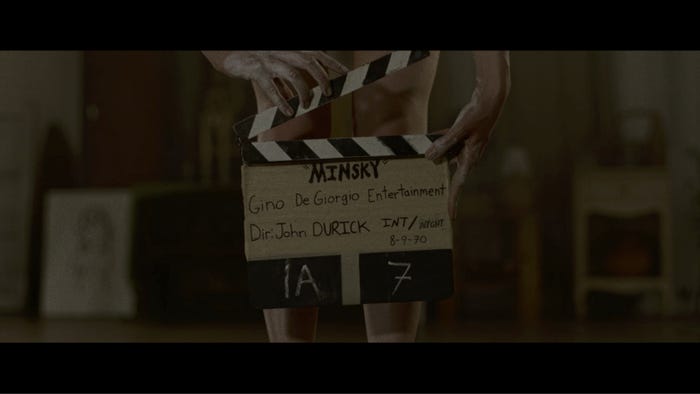

Immortality is an interactive game that captures the work of fictional actress Marissa Marcel, giving you access to three of her lost films, some behind-the-scenes footage, and multiple interviews with her and the cast of her movies. Through scrubbing through the footage, clicking on actors or props to see their connection with other works and a careful eye for detail, you’ll strive to find out why Marcel has disappeared.

Game Developer spoke with Sam Barlow, writer and director of Immortality, about what draws him to create puzzle games where there are rarely any clear answers, how he chose what editing abilities would work best for players wishing to explore Marcell’s film career, and about creating the Dark Souls of watching a bunch of movies.

Game Developer: Immortality leaves a great deal of the real story of Marissa Marcel in the player’s hands to figure out. Much of your work leaves a lot up to player interpretation. What draws you to this storytelling style?

Barlow: I played Dark Souls, originally. And obviously, I was plugged into the discourse around Demon’s Souls and Dark Souls and all the From stuff. But I started playing Dark Souls when my son [was] very young. And, my God, it makes it sound like I'm getting really old now, but now my son is old enough that he got into Dark Souls. He and his friends were playing Dark Souls Remastered and he's getting extremely deep into the lore. When Elden Ring came out, that was the first time since he's been really into this stuff that we both got to sit and play our own separate sides.

It was interesting playing that as it was coming out – seeing, in real-time, people trying to dig into the more obscure things. As a game designer, I like the brazen “We don't give a fuck” you see in some of that quest scripting. I really wanted to progress the Ranni questline, and I'm old school enough that I kind of feel like looking online is cheating still. So, I said to myself “I'm not stupid. I’m gonna give this a good go. I'm gonna figure this out.” And I just couldn't get the questline to progress. So, I looked online, and I found that I missed one vital Site of Grace that I didn't stay at because I had full health. I would never have done that if I hadn't looked online.

Then, I realized how much of that stuff is in that game. It’s an interesting thing because I'm always intrigued by friction as a concept. When I did Telling Lies, there was a deliberate decision (which a vocal number of people didn't like) where you can’t skip through the videos. And for me, it was really important because Telling Lies was supposed to be evoking a sense of surveillance and this real-time feel of watching people go about their lives. So, to me, having the player be unable to skip, and instead having to kind of scrub around, was an element of communicating some of the (I'm not gonna say tedium) friction of the idea of surveilling someone.

I'm always intrigued by friction as a concept.

I play Elden Ring and I'm thinking “I just spent three hours combing this village (that I've already been to four times) looking for a quest trigger here. Is there something I've missed looking into dark corners?” At that point, I was impressed at the amount of work people are willing to put into digging into the lore elements, quests, and more obscure aspects of Dark Souls and Elden Ring.

I'm really interested in that element. With Immortality, we tried to respect the audience, and there's a lot of story which is buried deep in there. There is story that is, texturally, not even present there but is underneath it. Those are the things that I think people can put two and two together. I really like the idea of people finding these hidden, obscure pieces and clips throughout the game. And this is exactly what happens in Elden Ring, right? Somebody finds a weird, obscure thing, tells their friends or their online community, someone else puts that with another piece they found, and together they unravel the story. That's the bit that's gonna be really fun.

Your work is often filled with secrets and twists. What do you feel goes into making these twists satisfying?

My touchstone was way back when I made Silent Hill: Shattered Memories. We knew that we were telling this story that was going to have, for whatever value it adds, a twist at the end. And I wanted that to be meaningful and not bullshit. So, I did lots of research and thought into the point of a twist. What a good twist? What is a bad twist? And how does one go about meaningfully, usefully setting up a twist? Which led to lots of arguments with Konami at points because there were people at Konami that felt that if you have a twist at the end of your story, then the audience should not see it coming.

I disagreed. A good twist is one where you’ve kind of had the idea yourself. You've rationalized it, but then you've dismissed it, and it's gone away. With a good twist, the story that is revealed by the twist is more complicated and interesting than the story before the twist. In delivering that twist, you're making the player’s brain and imagination a bit more work.

A good twist is one where you’ve kind of had the idea yourself. You've rationalized it, but then you've dismissed it, and it's gone away.

Your work with Immortality is filled with secrets that can be very obscure and complicated to find. What thoughts go into deciding how deep to bury your secrets? How to make those secrets approachable yet still hard to find?

One of the things I really got into when I was working on Shattered Memories was Gene Wolfe because he writes some of the best stories that have deeply-buried secrets. You read Wolfe and get to the end, and you're not quite sure what you just read. But you feel like somewhere in there, there is a truth. So, you'll get to the end, and it’s wild because you read The Book of the New Sun. It’s several volumes, thousands of words. You’ve read this incredibly dense, beautiful story, you get to the end, and you say “I have vague feelings that I understand some elements of this thing.”

Wolfe wrote books where you're supposed to read them three times. As an example, in his books, there's sometimes a single line on a single page that is the key to understanding something. Which is so very Dark Souls. I was really interested in this and wanted this to be present in what we’re doing with Immortality. The downside to Wolfe, for me, is that you have to sit and read thousands of pages of books from beginning to end, and then you have to go back and read it again. And then you have to go back and read it AGAIN. And in the modern day, when we have too much content and no time, that's a lot to ask.

I was aware of thinking, back when I was developing Her Story and Telling Lies, that I was making these games that were asking you to be as obsessive as a Wolfe reader. But, because you had the freedom to jump around or stop or replay, that it kind of accelerated that process. The internal pitch for Immortality was to try to tell Wolfe-like story with those deeper secrets, but in a way that was a bit more friendly to the audience without disrespecting them in terms of laying things out for them.

Immortality is a puzzle game where you never really know if you got the answer right. You can come up with theories, but there’s no “YOU ARE CORRECT. YOU WIN.” sort of moment.

Andrew Plotkin, who makes really fantastic interactive fiction, said (and he may have been quoting someone else himself) that the definition of a good puzzle was one where, when you have the solution, you don't need to confirm it because it just makes sense. That’s a loose paraphrase. Anyway, the hypothesis of Her Story was that we take away all of the game structure and shepherding that we use in these games. And does it become more interesting when we do?

And how did this lead to looking at filmmaking and editing? Creating a game around those things?

Immortality partly came out of having made Her Story and Telling Lies, as well as some other projects that involved a lot of filmmaking. There was a real pleasure in just being immersed by footage in the editing room and scrutinizing it. And looking at, say, a bunch of different performances and picking which frame do you want to cut out on? We've got these two versions of takes, which one is the one that has their expressions?

It's such a joy to scrutinize a performance in that way and which you would not do if it were in the cinema. There, you're watching an incredible performance on-screen, it just flies past at 24 frames a second, and then you walk out the door.

Why a film that’s out of order? And jumbled up with several other films?

There was definitely an anecdote there was pasted up on my wall. Early on, when we were conceiving of Immortality, I was really deep into a Nicolas Roeg trip and thinking about how he cut his films nonlinearly. For him, this was an attempt to create something that felt more like human memory and how we actually think.

There's an anecdote from him of when he first got his job in the film industry. He got into the room with the moviola machine. The first time he saw someone actually rewind film - essentially reverse the direction of time - it blew his mind. Walkabout is this movie he made about the Australian desert and kids wandering around it. There's a scene in that movie where there's a young Native Australian boy, and he sees some hunters kill a bison, and it's so upsetting to him. And it cuts to him, and then it cuts again, and you see the footage rewound. The bison’s coming back to life. which was the character’s attempt to undo what’s been done.

Hearing Roeg talk about this very innocent, beautiful pleasure of just playing with film and how that felt magical to him, [we] wanted to try to capture some of those little bits by saying, hey, it's a game. You can push your sticks and have fun with this, and like every now and then, feel that this is kind of fun and magical.

You can click on many different things in each scene to move to a different scene. Did you create the connections between each clickable element ‘by hand’? There are so many different things to click on and explore, so I am curious how you did that.

There's lots of fun logic in terms of how the game decides what we should cut to and what the game thinks is a good cut. And you know, you make sacrifices. There is nothing hard-coded in the game at all. It's all algorithmic. So, you sacrifice the control of deciding how you would cut it. But there's a lot of underlying logic that tries to kind of create meaningful things and point you in interesting directions.

How did you decide how much of that movie editing experience you wanted to give to the player?

When I first mentioned this concept to my agent, they felt like it was going to be like editing a film. And I think we did, at points, loosely talk about how we didn’t want to make Final Cut. We don't want to ask people to undertake the effort that would be involved in actually moving pieces of film around because that isn't necessarily the fun of it.

What we wanted was an experience that felt like having a friend say, “Oh shoot, I just found this crate of all this footage from a lost movie!” And you get taken to this old moviola and go look at it. There would be this rush of just grabbing stuff and sticking it into the machine and figuring out what this movie was. That was the point we wanted to try to recreate.

What about the look of each of the films, and how they each reflect specific times in film? Was there anything you wanted the player to get out of those?

I wanted players to think a little bit about the analog nature of them. This wasn't necessarily designed - we kind of fell into this - but we opened the game with a piece of digitized video cassette of a '60s TV broadcast. When you look at that, it's really pixel-y and shitty looking. And then you zoom in, and the pixels blow up more. And while it was on a very basic level, it asks the player to think about what even is film? What is digital video? It's just a bunch of dots, but you experience it as if there's someone alive on the screen.

What sort of work went into capturing the three different cinematic eras of Immortality?

We went out looking for people that could do bits and pieces and give us versions of scripts that would evoke that era. We tried to have things that were very authentic and, in terms of how we shot it, made sure we were using original historical lenses. It kind of fried a lot of the crew’s brains. Especially younger crew members, because we would be referring to processes that did not exist for them. Or, if we said something like matte painting, they would be thinking that this goes to the CGI people, and they put a 3D model behind our rotoscoped characters. No, no, we're going to put a painting on a piece of glass in front of the lens.

It was just important to us to have it be authentic enough that it was kind of interesting and useful. Obviously, you know, we weren't Fincher. When David Fincher does a film set in the '70s, he spends like a million dollars per shot having the CGI artist erase wheelchair ramps on street corners that would not have existed then and things like that. It's ridiculous micro detail. So, within our constraints, we tried to be as authentic as possible.

What thoughts go into turning movie editing, or looking through old films, into a game?

I was aware that, with Her Story and Telling Lies, people refer to those games as interactive movies. People stopped doing this now, but when Her Story came out I would do panels and shows and people would ask “Is it really a game?”

"Interactive movie" always struck me as slightly odd because, as someone that's obsessed with movies, to me, what defines a movie is the cut. If you see a movie, you're seeing somebody explicitly control a sequence of images that has been put into your brain, and that's part of the craft. Talk about Hitchcock and the mastery of the shot sequence, or you talk about how he deploys suspense, and it's all about that control in the cut.

With Immortality, I was thinking about how people keep talking about these things being interactive movies. That's when the idea, to some extent, was, “Well, let's talk about movies.” Let's make something that's about movies. The real question, then, was about how to keep it magical. Because if we just make a game of Final Cut, it's not necessarily magical, right?

The idea behind the mechanics in Immortality was that we're giving you something that's extremely freeform and expressive and powerful.

So, the idea was to still have an element of surprise. And while I'm making it, I'm really interested in the expressive side of video games. Which, I think, is partly when people ask me those dopey questions about whether my work is a game? Look, if we're talking about something being interactive and being a game, you know, a corridor shooter like Call of Duty, where it doesn't matter who's sat in front of the game, everyone will get pretty much the same experience. And that's a very poor version of interactivity. Whereas in my games, you play it, and it's the simplest game in history. In Her Story, at any point, you can decide what to type, and in theory, you can type any word in the English language and create a meaningful expression. And so, it rapidly becomes quite a personal, expressive game. If you two people - especially people in a relationship - sat playing Her Story, you get this interesting look at how different people react.

The idea behind the mechanics in Immortality was that we're giving you something that's extremely freeform and expressive and powerful. Mostly, you can stop at any point and click on something that looks interesting. And we will meaningfully act on that. So, you have a huge amount of control. At any point, I'm going to how we're cutting this thing. But at the same time, we're reserving some of the magic because we then get to teleport you and take you somewhere magical when you click on some element in each scene. There is something magical about clicking on someone's face and jumping 30 years into the future, and the character’s in a different situation. You know, there's an interesting spark between those two things.

We're gonna give you some of that magic, but it's completely in your control. That was pretty much the heart of the game.

You May Also Like