Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Fresh off her co-directing debut on King's Quest 6, Jane Jensen laid the groundwork for a more mature adventure game and adventure-game hero.

The following excerpt comes from Once Upon a Point and Click, a collection of retrospectives on the making of Sierra's King's Quest and Gabriel Knight adventure games. Once Upon a Point and Click is currently available from Story Bundle in a pay-what-you-want collection of books centered on game development and culture.

**

While Jane Jensen shared much in common with Roberta Williams, an interest in creating sing-song worlds filled with fairytale characters was more her mentor’s domain. “At the time, I was a fan of graphic novels like Hellblazer and [the works of] Neil Gaiman,” Jensen told me. “I wanted to do something that was a mystery, something that had a paranormal element to it. I came up with the idea of a guy descended from a long line of inquisitors who fight evil.”

Jensen kicked around several themes and settings for her inquisitor to explore. One of her first concepts was the backwoods of Germany, the setting of a string of murders that locals attributed to a werewolf. Jensen liked the idea, but saw a flaw. An inquisitor who jetted around the globe to solve murders would already be comfortable in his own skin. Established. For her first solo game effort, she wanted to tell an origin story.

Setting aside theme and setting for the time being, Jensen concentrated on fleshing out her protagonist. The name “Gabriel Knight” had a strong ring to it. She envisioned Gabriel as a modern-day Indiana Jones: a professor who specialized in the paranormal and had a penchant for adventure. Naturally, Gabriel got wrapped up in cases that contained supernatural elements.

"The story came first. Then I had to figure out how to make it work as a game designer."

Jensen considered her Indy Jones-style leading man, then dismissed him. One of her favorite archetypes was the flawed hero. Unlike Graham of King’s Quest fame, Gabriel struck her as a scoundrel. Handsome and bright, yet more likely to chase skirts than mysteries and hard work. He would also be a struggling writer. “At the time, I had tried to write a novel and didn’t get good responses from the agents I’d sent it to. I guess some of Gabriel’s writer-dom reflects some of my experiences at that time.”

Jensen turned to some of her favorite media for influence. She’d devoured Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire series of novels during college and became spellbound with New Orleans, the setting of the novels. While working at Hewlett-Packard, she had gotten hooked on Angel Heart, a psychological horror film starring Robert De Niro and Mickey Rourke. Rourke played Angel, a down-on-his-luck P.I. who walked a dark path littered with obstacles like voodoo priestesses and demonic possession.

Intrigued by the culture and mysticism of New Orleans, Jensen plunged down the rabbit hole. “At the time I wrote Gabriel Knight, I had never been to New Orleans. I really did all my voodoo and New Orleans research pretty much with books. Now everything I do is Googled, but at the time, I actually called a New Orleans bookstore and had them send me some picture books of New Orleans.”

The more Jensen learned, the more she fell under the spell of New Orleans’ voodoo scene. During the early 1720s through the early 1740s, most slaves exported from Africa arrived in the state of Louisiana. They carried no material belongings, but they did bring their religious practices and beliefs. When their slave owners attempted to convert them to Catholicism, the slaves played docile and pretended to accept their new doctrines. During the leisure time granted to them as gens de couleur, “free people of color,” they carried out voodoo ceremonies in secret.

On the evening of August 21, 1791, a voodoo priest called an underground meeting on the island of St. Domingue, a French colony. The meeting boiled over into one of the largest slave revolts in history. Hundreds of thousands of slaves and gens de couleur raped, pillaged, and plundered until the French withdrew and declared St. Domingue–later renamed Haiti–a free state in 1804. Not everyone was interested in staying. Citizens of all ethnicities fled to New Orleans, a city whose French culture and language seemed comfortable and familiar.

Over time, New Orleans’ mish-mash of voodoo coalesced into a practice known as Louisiana Voodoo. Practitioners believed there was one god; that He did not interfere in the lives of his people; and that spiritual forces acted as His liaisons, able to influence events on his behalf. Spirits entered the flesh of believers through dance, song, snake worship, and the use of special components called gris-gris.

Emerging from her research, Jensen set to work on an outline. “Generally, on all my games, I tend to write the story first. For Gabriel Knight’s story, I had just taken a class by [screenwriter] Robert McKee on story and screenplay writing. It was really, really inspiring. Sierra sent all the designers to that class; it was a three-day session in L.A. It was focused on things like positive and negative beats, subtext, and just a lot of things I’d never really thought about as a writer. I worked on Gabriel Knight’s story outline to include stuff I’d learned. So the story came first; then I had to figure out how to make it work as a game designer.”

Life started out simple for Jensen’s flawed hero. Gabriel spent his days staring vacantly at the blank page lolling out of his typewriter, which he kept in the studio apartment located in the back of St. George’s Books, his ailing used-books stores tucked away in New Orleans’ French Quarter. At the start of the game, he catches wind of a string of serial killings labeled by the press refers as “the Voodoo Murders.” At first, his interest in purely occupational. He views the ritualistic massacres as a dark and intriguing hook for a novel. A chance to hit the bestseller’s list and turn his life around. Jensen plotted a journey that would take Gabriel and adventure-game fans from New Orleans to Munich, Germany, where Gabriel learned several sobering facts. That he came from a centuries-old line of Schattenjägers, shadow hunters sworn to combat supernatural evils; and that his father and grandfather had perished at tragically young ages in the line of duty. Gabriel, it seemed, was doomed to follow in their footsteps.

To offset Gabriel’s flirty demeanor, Jensen penned a sidekick. Grace Nakimura was an overachieving, Japanese-American college student who ran the bookstore while Gabriel meandered around the city, and delighted in helping him research the “Voodoo Murders” case in her spare time. Grace was also female–just Gabriel’s type–and a character cut from a different cloth than most videogame heroines. She was attractive, yet petite, absent the double-E bust of female likes like Tomb Raider’s Lara Croft. She wore outfits that covered rather than exposed skin, preferred to spend her nights studying instead of carousing, and gave even better than she got when Gabriel sharpened his wit and turned it on her; indeed, their verbal sparring became a frequent and endearing habit of their interactions.

As a counterbalance to Grace, Jensen created Malia Gedde, a voluptuous socialite and the femme fatale at the head of the cult responsible for the “Voodoo Murders” plaguing New Orleans.

“I knew Gabriel had to have a sidekick, and I wanted sort of a romantic triangle. Grace probably represents me more than anybody else in the game. Gabriel is that bad boy who women love to like but know better than to mess around with. Grace reflects that. I wanted to make her a natural person. That also goes with the concept of who she represents to Gabriel: she’s not the blonde bombshell he would normally be attracted to. She’s very smart and bookish.”

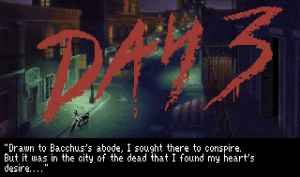

As the characters came together, Jensen solidified her story structure. Events would unfold over ten chapters. Every chapter began at the dawn of a new day. After Gabriel stumbled through the curtain that divided his cramped apartment and bookstore, chugged a cup of coffee, and engaged in witty repartee with Grace, players could hop on his motorcycle and perform adventure-game activities: converse with characters, pocket items that would come in handy later, and solve puzzles. Chapter by chapter, players would lead Gabriel closer and closer to the answers behind the mystery of the Voodoo Murders and develop his connection to Grace—culminating in a denouement where Gabriel confronts demon-possessed cultists.

Dividing the game into chapters enabled Jensen to skirt a common flaw that plagued adventure games, including early installments in Sierra’s celebrated King’s Quest series. Many games allowed players to advance even if they were missing a crucial item needed to solve a puzzle later in the story. When players hit such a brick wall, they had two options: reload an earlier save-game file, provided they’d had the foresight to keep multiple saves; or give up and start from scratch. Gabriel Knight’s day-by-day progression prevented players from moving on until they had talked to every character, gathered every item, and solved every puzzle needed to finish a given day, leaving them properly equipped to tackle the next day’s conundrums.

Dividing the game into chapters enabled Jensen to skirt a common flaw that plagued adventure games, including early installments in Sierra’s celebrated King’s Quest series. Many games allowed players to advance even if they were missing a crucial item needed to solve a puzzle later in the story. When players hit such a brick wall, they had two options: reload an earlier save-game file, provided they’d had the foresight to keep multiple saves; or give up and start from scratch. Gabriel Knight’s day-by-day progression prevented players from moving on until they had talked to every character, gathered every item, and solved every puzzle needed to finish a given day, leaving them properly equipped to tackle the next day’s conundrums.

Jensen took her story proposal for Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers to Ken Williams and met some resistance. Sierra’s co-founder had hoped Jensen would come up with something more whimsical—in other words, something more in the vein of his wife’s lighthearted King’s Quest series. Jensen stood her ground.

“It was my ambition to make Gabriel Knight a sophisticated, dramatic story of the type you’d do for a book or a film rather than just a framework [for a game], which is what a lot of adventure games had been up to that time. And I love all those games. I was a huge fan of them. But I wanted to see if I could make something a little more intricate.”

Williams had a reputation for supporting the creative vision of his designers. He approved Jensen’s pitch. If Gabriel Knight found success, Sierra would have another hit series under its belt. If it flopped, the blame would be placed squarely at Jensen’s feet.

**

The following excerpt comes from Once Upon a Point and Click, a collection of retrospectives on the making of Sierra's King's Quest and Gabriel Knight adventure games. Once Upon a Point and Click is currently available from Story Bundle in a pay-what-you-want collection of books centered on game development and culture.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like