Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Minit devs Kitty Calis and Jan Willem Nijman open up about how they designed their one-minute adventure game to be fun but not frustrating, and why time limits are great for emphasizing player choice.

Released earlier this month, Minit is a game in which you have just one minute to have an adventure. When your time is up, your little black and white character drops dead and respawns in its house, ready to start another adventure with a new minute on the clock.

Set in a sprawling NES-era Zelda-style map of connected single screens, devs may appreciate how Minit is carefully designed to break play into minute-sized chunks by spacing out special items, puzzles and characters to speak to across its world.

“We know how far you can walk in a minute so we can design the world around it,” says designer and artist Kitty Calis.

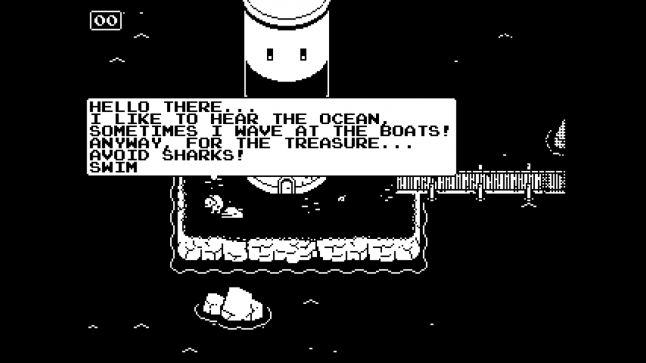

She describes an early scenario where the player encounters an old tortoise who sits outside a lighthouse and talks … very … slowly. In order to listen to all he says, you’ll need to make a beeline for him in order to get to him as early as possible so you have enough time for him to spool out his lines.

In your first true adventure, though, you find a sword on a beach that’s just south-west from the house in which you start the game. This is the sword that curses you to your minute-long lifetime, and the object of the game is to find a way of lifting it.

"We can make jokes not just with the text or the visuals but also with what people expect from a video game."

“The idea of finding a sword on a beach is ridiculous,” says fellow designer, and Vlambeer stalwart, Jan Willem Nijman. “Why would you pick up a weapon? That could only…”

”...Happen in a video game,” adds Calis.

“It can only cause trouble, which is the joke,” continues Nijman. “I guess a lot of the design plays off people’s expectations, because we can make jokes not just with the text or the visuals but also with what people expect from a video game.”

Like many Zelda and Metroidvania games, your passage through the world is gated by objects which can only be passed with the use of items, which in Minit are permanently collected while the world largely resets between lives. The sword allows you to cut through bushes which block off exits, while the Gardening Gloves allows you to chop down trees, and the torch allows you to see where you’re going in dungeons.

Slow talkers can be the death of you in Minit

And like Zelda, especially Link’s Awakening (“I played Link’s Awakening as a kid but I never really ‘got’ it,” says Nijman. “I was too bad at videogames back then,”) Minit’s environments are stuffed with things to do.

“We wanted to make a really dense game without any filler,” Nijman says. "There are no repeated puzzles and it’s not about fighting hundreds of enemies. It’s more that every screen brings something new, which adds to the sense of discovery.”

He and the four-strong team, which included sound designer Jukio Kallio and artist Dominik Johann, began by laying out the area around the first house, filling it in, bit by bit, with the rule that no single screen should be without some sort of puzzle or secret.

Some of these features are vital to progress, such as entering the lighthouse, where you’ll grab an important item. But others are optional, either only useful or just an interaction that does nothing.

Near the start, for example, there’s a screen where you have to cross an area inhabited by an angry bull which, when it sees you, charges.

“But you don’t have to fight it, you can decide to run around it,” says Calis. If you do fight it you get rewarded with a heart, giving you more health.

Other interactions reward playful thinking, such as trying to water the dog at the first house with a watering can found nearby. When it shakes it’s coat it rewards curiosity, a moment of connection in which the player discovers whether the game’s designers think like they do.

"We wanted to make a really dense game without any filler...every screen brings something new, which adds to the sense of discovery."

“It’s something we enjoy in video games,” says Nijman.

“Like the lightbulb test!” Calis interjects.

“Yeah! When you play a first-person shooter, for us, the first thing we do is to shoot a lightbulb and if it breaks it’s a good game, and if it isn’t it’s not worth playing.”

And more than that, these incidental secrets smooth out players’ experiences. “We wanted to make sure that if people are stuck and start trying random things they’d get rewarded for that. So having this dense world with all those secrets really helped there,” says Nijman.

However, these moments are more clustered around the houses where the player spawns so players didn’t develop an expectation that they should embark on potentially frustrating excursions to far-away locations to try out interactions.

“But also we really love hiding things in plain sight, and having them close to where you spend 20 or 30 runs,” he says. “It only makes it funnier when they find them.”

“Yeah, because who’d think of finding a coin in your own house?” says Calis.

When you tell players that they’ve just a minute to go have an adventure, their natural tendency is to rush off to get as far as they can, so placing valuable items close by is a way of subverting their assumptions, something that Calis and Nijman have enjoyed watching in Twitch streams since Minit released.

“As long as they’re having a good time then it’s fine, but I don’t want people to feel it’s frustrating and hate it,” Nijman says. “If they’re trying things and spending time exploring and being curious, that’s all we can wish for.”

Minit starts quite linear, with points of progression placed one after the other, but later the game opens up, facing players with several choices. One of the design intentions was for players to notice and remember loose ends and build up mental lists of things to do before picking one and heading off.

The minute therefore adds a layer of planning and intentionality to the game, but Minit avoids its time limit feeling like a restriction by asking players to revisit earlier areas and presenting them with a mix of progression-opening puzzles and long-running, multi-life quests involving collecting coins and finding hotel residents.

“Because it’s so dense and there are so many secrets, every time you move on to the next area you won’t have completed the last one,” Nijman says. “The world gets bigger and bigger, and you’re missing little bits. Most people who beat the game, it takes them two or three hours and they’ve seen only half the items and coins.”

And while the main game gives players a minute to live their best lives, almost all its puzzle and features are actually tuned to be completed in 40 seconds, which is the limit you get if you attempt to play its New Game + mode, which unlocks when you finish the main game. While Minit imposes a hard time limit, it turns out that a minute can feel surprisingly comfortable.

“We just want people to have a good time,” says Nijman. “Kitty came from Horizon Zero Dawn and I’ve worked on Nuclear Throne and both are really big, really hard, really brutal games, in a way. For Minit we wanted to make something that’s really friendly.”

You May Also Like