Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The creators of Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator designed purposefully taxing elements within the game. Here's how that friction work to make for a more meaningful experience.

“Transcendent, singular gaming experiences cannot exist without friction.”

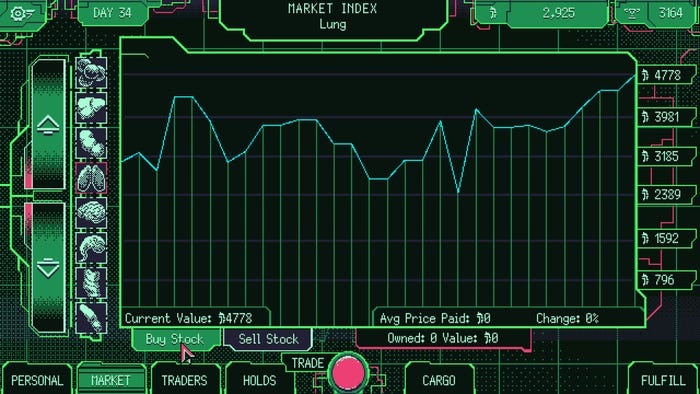

Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator is an experience in finding buyers for a starship filled with body parts, buying, selling, and trading for top dollar so you can become wealthy through the organ market. Its systems will push players pretty hard, challenging them to keep up with client demand, the organ selling market challenges, and the fact that some of your organs eat one another. It can be demanding, to the point of feeling taxing and unfair. But this is all by a purposeful, meaningful design.

Following a deep dive into Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator's narrative arc, Game Developer spoke with Xalavier Nelson Jr. to discuss the purposefully taxing elements of the game, the “friction” it creates for the player, and how that helped contribute to making the work a more meaningful experience.

Game Developer: What is purposeful friction in games? What is that purpose behind it?

Nelson: When I talk about friction, I’m referring to every time the player is forced to adjust from the brain that they use in everyday life, to the perspective and mindset of a different world. It can be a unique control scheme, a design that forces you to practice new rituals to succeed (Papers Please being the most prominent example), or even something as simple as using in-world terminology for common objects. The best-case scenario of friction is that its presence quietly and insistently enforces the reality of the world we want players to be immersed in.

The degree to which we are constantly tempted to reduce the virtual lives of our characters, the virtual lives of our NPCs, and the virtual worlds that we've built for the purposes of a moment's convenience is honestly pretty stunning—and it’s often for valid reasons. Accessibility and playability are immensely important. However, it’s easy to adopt an attitude that convenience is king, above building an experience that is true and cohesive unto itself, and this is the point at which we lose so-called ‘jank’ that was actually needed for our games to feel whole.

I think players can feel this absence, even when they can't verbalize it.

What sorts of shortcomings do you feel may be integral to a work? That can be removed?

If you had infinite time and budget to make a game, I believe it’s still entirely fair for you, as an artist, to choose the limitations that define your work. Or for your work to, in some way, be compromised! You're a flawed human being, making a flawed execution of a flawed creative vision. The word ‘flaw’ in itself, when applied to art, is not an inherent detriment. It is instead an acknowledgement that we are communicating to each other in the limited way that we can given our limited time and perspective in this universe, and that this is in fact what makes those words exceptional.

My point isn't that things should not be fun, but that so-called ‘shortcomings’ can be a critical part of making them fun, especially when intentionally chosen. With that context, it's been kind of jarring to play critical pieces of game canon for the first time and see imaginary Steam reviews pop up in my head. If Silent Hill 2 was released for the first time today, I’m fairly sure it would have negative Steam reviews for how foggy it was. Are those theoretical reviews correct? Yes. And are all of those theoretical reviews also wrong? Undoubtedly.

What are some other examples of older games with frictional elements that come to mind when you think on this concept?

I think there's something really interesting to be said here about Animal Crossing. There were characters in earlier Animal Crossing games that are vile. That were horrific, unpleasant jerks to exist alongside if you missed a few days in your town, or would just make you feel bad for existing. Even Resetti, the mole! Imagine being a child and you turn off your console without resetting or saving, and then a mole pops up out of the ground to scream at you for five minutes. “You didn't fucking turn off the console the correct way and this is your fault.” You say “I’M SORRY!” in your mind, and he says “I hope you remember because I'm union!” and then he goes back into the ground [laughs].

I can acknowledge the degree to which Animal Crossing: New Horizons is undoubtedly one of the most positive and necessary spaces we've had in these years of the pandemic, while also seeing that the sharper edges to that world which have been abandoned over time also mean we have less opportunities for those digital universes to make impressions on us that stick around forever.

Now, there's always caveats and nuance to be had in conversations like these. Still, games that present me with bad times along with the good times, especially to align with a specific creative vision? Even if I only remember the bad parts of that game in hindsight, they're so much more memorable than the dozens of mediocre games I've played over the years that simply presented me with an airless chunk of whatever they were supposed to represent before passing out of my life entirely.

What specific frictional elements did you put into Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator?

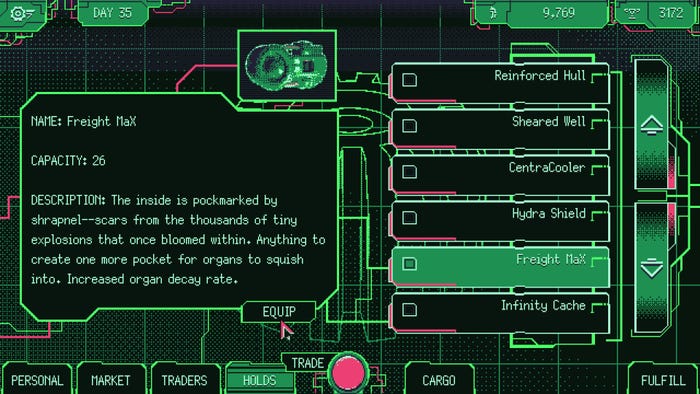

So many! One of my favorite examples is that organs can affect each other when they go into your cargo hold—and all of this is happening during a trading day. So, while you're trying to buy, sell, trade, and fulfill the requests of clients, you could have organs that are eating each other. And unless you're paying attention - unless you're shifting things around and making sure everything plays nicely - you may not know.

I adore this concept of (and maybe this is the ADHD talking) riding the razor's edge of stimulation. Knowing what matters and when it matters, and finding that when you were looking in one direction, something delightful or awful has changed. Because in the moment where you are putting out fires, you are entirely engrossed in the thought processes of a different universe.

There is a version of this game where we just have a hull that exists to form your inventory capacity. And you can upgrade it in a linear way. And it's not just a fundamentally less interesting game, but it's also a game that fundamentally communicates less with the player, as they're playing. Every system arranged within a game’s overall landscape is a moment in which the player and the developers are abstractly having a direct connection and building an experience - together.

How do you choose these elements to affect the player through friction?

When we go through the process of building a game, the team is constantly discussing how to align every element with our intended experience and story. Maybe this is weird, but we design compromises and negative experiences as carefully as the many tweaks and features and bug fixes we place to solely provide what's hopefully a pleasurable experience. I don't see a difference in design between friction and positivity, because they are all aligned to create a singular experience in our players lives.

Again, just because something is jank or not enjoyable in the moment, that doesn't mean it hasn't been designed, or put there on purpose. And I would even argue that as designers, we should proactively look at pieces of our experience that we know will be compromised or seen as unenjoyable, and find a way to make those downsides in some way contribute to a larger vision of the project.

Does this purposeful friction cause difficulties with some of the player audience?

For what it's worth, the majority of people, both on Steam, and a variety of other forums, seem to have really connected with Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator. We shipped what we intended to ship, and people are understanding that to a degree that is so liberating and gratifying to see. It’s very relieving [laughs].

That said, it is interesting having conversations with people who did not enjoy or understand a given intentional constraint in the way in which the game was built, and feeling a bit tongue-tied in the language to go through that conversation. Because it doesn't feel like there's many precedents for it. For saying “I’m sorry that this piece of the experience does not work for you, but that is what makes it work for everyone else who is enjoying the experience within the framework of what was intended.” There is conflict there, I guess partially because we are a medium that has an additional set of criteria, which is playability.

Playability is important, but there’s an insidious dark side to it, which is: “is it playable for me in the specific way that I want to play it,” which is not always going to be the case—and can’t be the case if we want this medium to grow as an art form. I’m finding it very liberating these days to play games and bounce off of something. That just means I can play a different game, the same way I would go to a different movie, or a different book, or a different piece of music. It feels a little bit scary that it's only more recently that I've applied that perspective to games, despite that creator-first framing being such a priority of my artistic career to date.

I feel like this is why it's so important not for us to have an aggressive or antagonistic or dismissive attitude towards our players, but to collectively begin to use more respectful and clear language that communicates our artistic intent as a priority. This is how we open doors for our players that would never be possible otherwise—and the more we can communicate that to our players, the more receptive I believe they will be to experiences that defy their initial expectations or desires. A medium that continues to generate those specialized, specific, cohesive worlds, just means their next favorite title is only around the corner.

You May Also Like