Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Relic Entertainment studio design director Alexandre Mandryka outlines a framework for looking at how game design is handled, which he argues will both allow the discipline to grow in value and expertise while ensuring it serves the needs of projects.

[Relic Entertainment studio design director Alexandre Mandryka outlines a framework for looking at how game design is handled, which he argues will both allow the discipline to grow in value and expertise while ensuring it serves the needs of projects.]

Over my 10 years in the video game industry as a designer, including three years as studio design director for Ubisoft Montreal, I've had the opportunity to collaborate on numerous projects from different companies and cultures.

While visuals and programming are better controlled, difficulty in anticipating, analyzing, and generally understanding the added value resulting from game design persists. While it is essential to game creation, this discipline is not clearly established and expertise is very rarely recognized.

This puts designers under so much pressure and gives them so little opportunity for reward and growth that they are trapped in a vicious circle of being at the same time paramount and overlooked. This is what I've come to call the Designer's Curse.

Most developers work in games because of their passion, which functions as a source of motivation, but it can also blur judgment as long as the pleasure of playing games and of making them stays intertwined. The beauty of a work of passion is that it is rewarding and fulfilling, as it caters directly to one individual's intrinsic needs, competency, autonomy and relatedness.

Because game design is such a young discipline, and also probably because games are generally viewed as not serious, its essence is not clearly established, making it a confusing path to follow, and grow in.

This article describes the difficult situation in which designers find themselves when not properly driven, offers a workable set of responsibilities and skills for them to own and develop, and defines a role for the game designer in the grand scheme of a project.

Like most things related to creativity, game design has always suffered from a lack of understanding. Most of the public thinks game designers just play games all day long. Executives tend to think they are the best game designers in the room or simply do not understand the designer role -- besides the fact that they need some on the payroll. A game enthusiast even once asked me if I was designing clothing for characters in video games…

Designers or aspiring designers I have met and worked with are rarely at ease. Most of the time, they feel that they are not heard or taken seriously, that they don't have the tools and support they need, that the complexity of their work is not acknowledged, nor the value of it understood.

Part of the problem is that the job of game design is generally not well defined in terms of skills and function. Game design is not as established as programming and art. Its academic status is in its infancy, which makes it difficult not only to execute, but also to discuss, since we lack a proper vocabulary to describe it.

This generally has two consequences. First, because no clear technical task is given to game designers, they tend to travel along the path of least resistance, as players also do in games, and try to do what they believe "being creative" is: coming up with ideas, and trying to have them accepted and put into the game. After all, games designers must design the game, right?

But as ideas are being proposed without any technical backing in terms of feasibility or relevance, and consequently no established authority, the ensuing discussions are generally just exchanges of opinions in which a producer, as the higher hierarchical decision taker, usually has the final say.

It is only natural then, that a designer, whose main measure of success is how many of his decisions are being accepted, evolves towards the producer position, making the game designer job even more devoid of essence.

Second, in some teams, game design and product vision can be merged into one single entity. Saying that they are the same thing is missing the point that the former is a means to the latter. As with any creation, the form has to be subordinated to the function.

Second, in some teams, game design and product vision can be merged into one single entity. Saying that they are the same thing is missing the point that the former is a means to the latter. As with any creation, the form has to be subordinated to the function.

Design has to be used to support the game's intention, even at its own expense. Some games, for example, can propose awkward player controls just because they support the overall product intention, just as some music composers can use dissonance in order to create the desired effect.

Merging game design and product vision has the consequence of limiting the medium's expression to the typical conventions of design, instead of challenging it to bring new solutions to the table.

For instance, a designer working on controls will by default try to create the best, most efficient, easy-to-use input system, but if the intention commands it, controls may be done in a less transparent way to give flavor to the experience.

Let's take the canon example of the survival horror genre. These games share a common experience with horror movies and thrillers that rely on frightening the audience with different tricks. Empathy with endangered characters is a typical example; that often takes the form of someone trying to limp away from imminent danger.

Difficulty of movement creates trepidation and frustration that build up the feeling of helplessness and ultimately fear. No wonder games like early entries in the Alone in the Dark and Resident Evil series are almost infamous for featuring clunky controls, further hampered by camera angles that sometimes force the player to aim at off-screen foes.

Inefficient controls can be needed in order to create a specific experience for the player. Of course, in order to achieve this, you have to see beyond good design for the sake of it and understand how it can play its role in building the overall experience.

This shows the importance of the distinction between intention and technique. That's why design or any other technical field should not be taken as an end in itself.

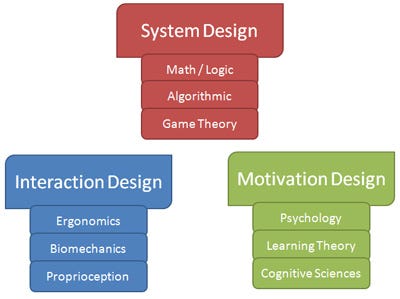

Can we deconstruct games and determine what skills can help design them? Making sure we regroup these skills orthogonally will allow for an easier way to learn and develop skill groups, and offer opportunities to specialize in them if required.

Rules, math and logic: System Design

In its most basic form, a game needs goals, rules, and general conditions that control the way the game unfolds, and establish processes for players to play and try to win. Because of the mathematical/logical nature of rules and conditions, it seems clear that analysis, logic and algorithmic will be relevant skills.

As these skills will also help create systems, state machines, and AI trees, we will call this branch of game design System Design and we will be set to design most of the rules and mechanical parts of games.

A typical example of the use of mathematics for game design is found in all games that rely on randomness. It's obvious that the calculation of probabilities is required in that case, either for payoffs or for odds of occurrences. In fact, an understanding of mathematics is going to help in most aspects of a designer's job across the board.

Interface, controls and readability – Interaction Design

Now that our game has rules and that they are stated clearly so that our player can understand them, we need to communicate the game state to our player so he can make decisions based on his understanding of the rules, and then input his decision back into the game world, basically "play his move."

The discipline that studies these aspects is ergonomics, and while less absolute to grasp, ergonomics is a well covered field that can help design interfaces, which give the right information to players, as well as controls that make it easy, even enjoyable, to input back into the game. Of course, depending on the type of interface considered, knowledge of biomechanics and cybernetics can also come in handy. For lack of a better word, let's call this second branch Interaction Design, as it focuses on the output/input loop between the game and the player.

When dealing with human-machine interfaces, knowledge of the principles of human body operation at the mechanical and psychological level leads to efficiently designed interactions. It is key, not only when trying to adapt a mouse-based interface, like FPS controls, to a gamepad, but also now that we're dealing with touch-based controls and gesture-to-full-body-movement interfaces.

Ergonomics was created to focus on making work tools and environments as comfortable and as efficient as possible. Now that we are applying its conclusions to entertainment, we have to learn to design enjoyable interfaces. Working in conjunction with human expectations like inertia, gravity, rhythm, and the action-reaction loop can give more of a natural, and thus enjoyable, experience, through what Steve Swink (Shadow Physics) described as "virtual sensation".

Reward, frustration and learning – Motivation Design

The last, but so essential, branch is the one that ensures players are so engaged that they actually want to play. Our motivation is largely based on chemical neurotransmitters that reward our brains and body through pleasure, generally in response to behaviors that help develop our evolutionarily selected traits. Endorphins make us feel good after physical exercise, dopamine rewards us when we understand something new, or establish new social relationships and so on.

Because we play games for the main benefit of entertainment and pleasure, understanding what is going to please our brains and bodies is essential to creating relevant experiences. Psychology, the neurosciences and cognitive sciences are obvious fields that will bring insight into these aspects and will strengthen an approach to the third branch of game design that I call Motivation Design.

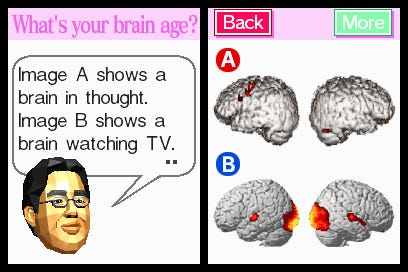

Brain Age deals with issues that everybody can relate to.

The emergence of casual games was made possible by improving the perception of benefit to a type of player that was not motivated by the benefits of core games. Nintendo's Brain Age series is definitely a typical example of this.

First by advertising the benefit of "mind youth", a real-life associated benefit that would resonate with customers beyond the core gamer audience, then by a mix of constant praise, slow difficulty progression, scheduled reward, even some tempering with guilt when the player would miss a session, these games really established a standard on how to motivate non-core players. This is obviously becoming of growing interest within the industry, especially through the growth of the social games market.

Now it is my belief that because the three branches of System Design, Interaction Design, and Motivation Design are quite orthogonal and also constituted of established and academically studied disciplines, it becomes possible to use existing literature to improve in each, create a workable vocabulary and even establish a career path for designers that would want either to specialize or diversify in each.

I think this approach would go a long way for managers to help their understanding of the game design position. It would better integrate game designers in the development process and help them in the hiring process, as well as in task assignation, and ultimately, performance reviews.

Note: I'm leaving level design out of the scope of this paper; this is not because it is of less importance, but just for simplicity's sake. Similarly to mise-en-scène, level design can be argued to be of a higher level than game design, as it aims to build a directed experience for the player, using elements of other technical fields in conjunction.

Historically, level design has been considered as game design's little brother, but recent blockbuster games have clearly showed the importance of thinking otherwise. A similar analysis could be done for that design discipline, also leading to better specification and understanding.

Even in the simplest games, game design should be subordinated to the product's intention; however, it is very important to keep the distinction between the two very clear.

Game design, just like all other disciplines on a project, is here to help support the intention so it can be delivered to the final consumer. As a step between product vision and implementation through code, it reflects on the intended experience and proposes concrete rules and systems that are actually conveyed to the player, not only through the content presented, but also through the choices and challenges he will have to face in game situations.

As Griesemer and Butcher stated in their 2002 GDC talk "The Illusion of Intelligence", their intention in Halo was to make the player feel like Schwarzenegger.

The conjunction of the low enemy accuracy that gradually improves with constant exposure of the player to foes, and the fact that the player's shields regenerate after some time away from combat favors the engage/cover routine that Predator's Dutch uses during the outpost attack, thus ensuring that players will follow that routine.

In an industry, creation is always a top-down process that trickles down from intention to execution. Not only because it reassures the guys in suits, but also because it's the most efficient way to ensure that a collaborative project focuses on a given experience instead of becoming a juxtaposition of inspirations aimed at different targets.

The vision holder has to clearly state his intentions, then turn towards his specialists and ask them to propose technical solutions for the intended experience to transpire through the game. For this, they have to be entrusted with ownership over their specialties so they can feel they have enough autonomy to be creative.

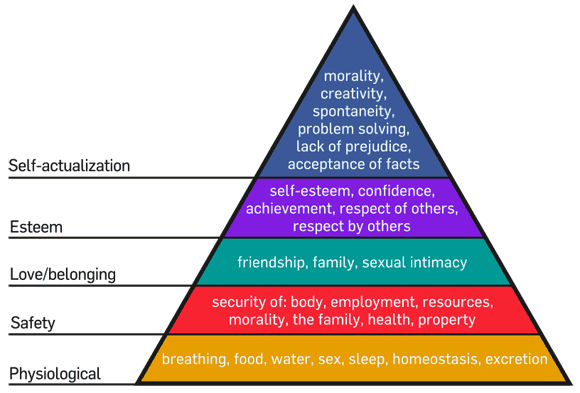

It's at that point that they can feel safe enough to engage in creative thinking at their level of intervention and take part in building the whole structure. Maslow showed in his hierarchy of needs that the esteem level needs to be secured (self-esteem, respect by others...) before one can be at ease at the self-actualization level and tackle creative tasks.

Being recognized as a specialist and owner of a specific domain gives the designer the confidence to be responsible for a given part of the production. This is where the designer develops a sense of pride for what he does and naturally wants to improve, as he's being motivated at the intrinsic level. This is not to say that every discipline should be separated and keep their ideas for themselves. Quite the opposite, when someone is being respected for his skills, he is more likely to freely share his ideas with the rest of the group, and have them developed by whoever has the most adapted skills to do so.

Game designers need to focus on identified technical tasks, and be given ownership over them. That is the only way they can develop as individuals and as team members.

Once established as technical providers, game designers need to understand the overarching game vision, and come up with solutions in their area of expertise to support it and make it tangible to the player.

When that happens, on that day, we'll have lifted the Designer's Curse.

Three keys to a healthy game designer

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs image taken from Wikipedia, under Creative Commons license.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like