Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

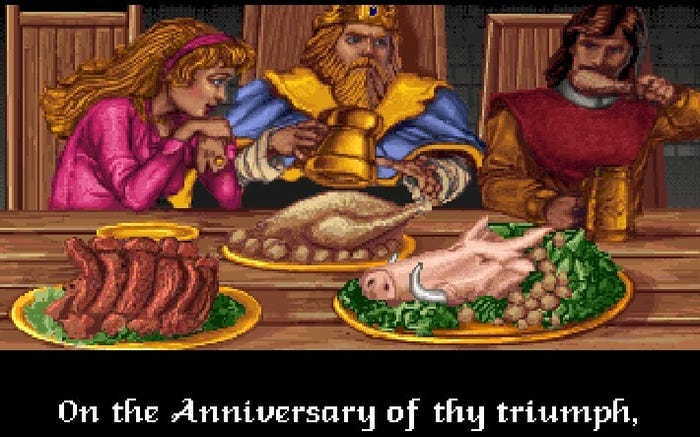

Ultima Underworld creative director Paul Neurath returns 30 years later to talk about the progenitor of the "immersive sim" genre.

30 years after the launch of Ultima Underworld, one of the most ambitious 3D games of its era, its original creative director somehow still hungers to do for modern video games what his classic "immersive sim" did for games of the ‘90s.

"The only reason I'm still doing this today is, I see creative opportunities to innovate," longtime designer and programmer Paul Neurath says from his home in Massachusetts. “The industry is still immature.” The industry veteran doesn’t come to this conclusion lightly, having programmed and developed games since the mid ‘80s.

But after a fumble with the 2018 launch of Underworld Ascendant, Neurath is taking an anniversary-timed opportunity to reflect on the original Ultima Underworld—to tell its stories and to recalibrate his current game-making compass.

Ultima Underworld heralded a new wave of first-person action gaming, even if its impact took years to bear out in the larger market. While it never achieved the widespread fame of controversial shooters like DOOM and Wolfenstein, UU eventually racked up over half a million units in sales—which Neurath says came well after the game’s first 90 days on store shelves ("That was a genuine surprise"). And its robust 3D tech, as combined with an "adventure however you want" mindset, eventually inspired the likes of Thief: The Dark Age and System Shock, two series that Neurath contributed overall creative direction to.

Neurath knows where his game’s impressive tech, complete with first-of-its-kind 3D texture mapping, lands in the PC gaming timeline: "Wolfenstein 3D came out a few months after Ultima Underworld, so we kind of, in some sense, beat id Software to the punch." He pauses. "Not that that matters at all."

And he means it: this many years later, the concepts behind Ultima Underworld matter more to him than the texture-mapping advancements. His college experience had little to do with his selected major of environmental science; instead, he says he focused on running Dungeons & Dragons sessions with friends. He laughs while recounting a session where he told his players that they’d been tasked with defending a village under siege. "The players decided the best way to deal with the bandits was to just burn down the whole village," Neurath says. “That would scare the bandits away, technically."

He added programming to his college courseload "on a lark," only to get hooked. He describes his course’s final project as "a 3D, real-time, first-person, multiplayer, space combat game,” built from scratch on a DEC PDP-10. "You had to use your imagination, but the gameplay was, like, 'wow,'" Neurath says. "Maybe a computer is another way to create worlds, as opposed to pen-and-paper. That was an eye-opener for me."

In the years that followed, Neurath cold-called the publisher of Wizardry to strike a deal for his first Apple II game, followed by freelance work on games like Chuck Yeager’s Flight Trainer (an early "platinum"-selling title). His most formative break came when he looked at the box of a recent RPG he loved, Ultima II, and realized the address was roughly 40 miles from his home.

That distance soon became his regular working commute. One day, he drove to Origin Studios, knocked on its doors without an invite, and struck up conversations with founding staffers like Richard and Robert Garriott and Chuck Bueche.

"In short order, they said, 'we have a lot of extra office space, if you just want to have an office and work out of it,'" Neurath says. This kicked off a period he describes as his "graduate school," as he was put to work in a small role on Ultima III and IV, and did some AI programming work on Ogre, a port of a Steve Jackson board game. "The AIs were nothing special by today’s standards, but they were good enough to beat Steven Jackson nine times out of ten," Neurath says.

Though he’d loved the Ultima series before getting office space at Origin, Neurath absorbed even more when rubbing elbows with its creators: how to create "worlds that were living on their own," full of NPCs living their own lives, and how to manage moral and ethical choices, where "there was no clear 'right' or 'wrong.'"

Yet when the Garriotts spearheaded a major company shift from NH back to their home state of Texas, Neurath didn’t follow—even after being offered a full-time role as the Director of Development, which he turned down due to family ties in the greater Boston area.

Yet he was also burnt out on the three-year grind he spent completing 1989’s Space Rogue, which he attributes in part to the company’s move away from NH, leaving him to make the game "virtually on my own," he says. (On a programming level, Neurath rewrote DOS "from scratch" to recover more precious memory, so that Space Rogue could run at all. Surmounting this challenge was but one reason he found himself working “60-hour weeks” on a regular basis.)

The only way to make the D&D-like game of his dreams, where players would be empowered to make unexpected choices—all while sporting first-person tech beyond Wizardry’s slow "turn-based line drawing" system—in his home state, he figured, was to start his own studio, build a team, and create his own IP.

On a programming level, Neurath confirms that the texture-mapped 3D core of Ultima Underworld came partially from graphics engineer Chris Green (as well as several other UU team members), who he met while working on the Chuck Yeager’s Flight Trainer series. The rest of Neurath’s newly hired team at Blue Sky Studios (which eventually renamed to Looking Glass Studios) built gameplay systems and other important technical upgrades on top of that code base.

There was a prototype up and running within three months of the team getting to work. Within a year, that studio’s pitch of a fully 3D action-RPG with major player-choice ramifications, and an impressive proof-of-concept demo that ran on the era’s 386-powered PCs, was rejected by nearly every potential publisher. "There’s no market for this," Neurath recalls hearing a lot in the spring of 1990, even from PC-friendly publishers he’d worked with like EA. Once again, Neurath found himself cold-calling the team at Origin, now headquartered in Austin, TX, to see if they’d bite.

"There could be some cool potential here," Neurath recalls them saying, "but we think it should use the Ultima brand. We’d be cool with that." This was the Summer of 1990.

"I don’t think I ever said this to Richard and Robert [Garriott], but the only hesitation I had was that our vision was to make a completely original game," Neurath now admits. And he knew, having seen Ultima game development up close, that Origin might spend a lot of time "vetting” his game to "fit the Ultima sensibility."

But Neurath took the offer back to his new studio to decide as a team, and they agreed: Ultima already inspired the kind of game they wanted to make, and it would commercially benefit from Ultima’s branding and fandom.

That is, until that very branding was nearly taken away. "There was a scenario where [Origin] would have walked away from the game," Neurath says. Roughly one year into development, Origin became unsure about the game’s "focus on action."

They weren’t happy with the narrative, which Neurath originally led: "it needed work, for sure, and I wasn’t a great writer by any stretch. Mediocre at best."

On a performance level, Neurath is blunt: "The frame rate sucked." The game’s pre-alpha version could reach 15 frames-per-second performance on a commercial 386 PC "on a good day," he says, but it more typically ran lower than 10 fps. And the adventure-how-you-want aspect of the gameplay still wasn’t gelling. “These immersive sims tend to come together late,” Neurath says, pointing to similar development issues in series like Thief and Deus Ex.

Neurath was in over his head: he was leading a brand-new game studio, made up largely of fresh college graduates (including one engineer, Doug Church, who was still finishing a degree at MIT), and trying to convince a publisher that they could get an ambitious-yet-undercooked game over the finish line without tarnishing arguably the biggest Western RPG brand in the PC gaming space.

He had to buy time. So he did—almost literally.

"Frankly, we convinced [Origin] by saying we’d cover the remainder of the [development] cost, effectively," Neurath says. While building Ultima Underworld, his team was simultaneously juggling a port of Electronic Arts’ upstart Madden NFL ’93 to the Sega Genesis, complete with up-front cash and a royalty arrangement.

That project was going well, and sports gaming appetites on the Genesis were exploding. Neurath did the math, then made what he admits was less than a sure bet. He’d fund the remaining "lion’s share" of Ultima Underworld’s development out of his own pocket. Origin agreed.

"Look: part of being an entrepreneur is being kind of crazy," Neurath says. “Warren [Spector] and I have talked about this a lot over the years, that when you make these innovative games, you have to accept the risks. It can be foolish, right? You can crash and burn. But you have to be willing to take that risk, or you won’t innovate.”

Neurath had met Spector, then a little-known story designer and writer, while working on Space Rogue, and during the aforementioned UU turmoil, he asked Spector to come on board as a producer (and replace two other producers who’d left the project). "We had a shared mindset in terms of gameplay and games we liked," Neurath says. "He really gelled with our team."

Neurath suggests that Spector’s involvement may have made an even bigger impact on the game’s eventual release than its revised financial plan. He more effectively communicated the team’s vision to Origin, particularly the pessimistic sales and marketing groups.

Spector also helped overhaul the narrative beyond its original skeleton, which freed Neurath to focus on level design for the game’s first two levels, out of eight. "I did that because pretty much the rest of the team had never made a commercial game before," Neurath admits, though he makes clear that Spector and the rest of the team chipped in on other major design decisions.

Neurath concedes that his team’s juggle of UU and Madden ’93, which financially paid off, took its toll, particularly in the form of 80-hour work weeks for the staff: "I had my hands full, and I made a lot of mistakes, and it's fine. That's what entrepreneurs do." He still regrets that the game adopted D&D-styled stats for characters, like strength, dexterity, and intelligence, which he conceded to play nicely with the Ultima brand.

His original vision revolved around the player’s choices impacting how well an action played out, instead of points on a page. (Run and charge to make an attack more powerful, instead of relying on extra points on a spreadsheet, as an example.) He tells fans to look at how creation and development systems worked in the 1994 game System Shock: "That’s really what we wanted to do with Ultima Underworld."

While he’s proud of the technology behind UU, and how his team built a number of "never-before-seen" gameplay mechanics into the engine, he laughs at how his team managed UI and player movement. “Before Wolfenstein and DOOM, mouselook wasn’t a thing!" he says. Members of the UU development team tried to wrap their head around first-person movement by holding camcorders at eye level, walking around, and reviewing the VHS footage, which helped them understand and implement the concept of virtual "head-bobbing."

But the game’s original movement system, which revolves around an on-screen cursor that alternates between inventory management and head movement, paled compared to what id Software and others delivered shortly after. "I was like, duh," Neurath says about seeing competitors' games, then smacks his forehead.

In hindsight, Neurath still believes the game’s development staff of mostly fresh college graduates paid off for a huge reason: "New hires don't have a sense of what they cannot do." He points to an exception on the UU team who would interject and exclaim, “You can’t do that, that’s not how games are done!”

Neurath says he "couldn’t solve that for that person." Instead, he relished putting problems in front of fresh talent: "throw the challenge down and see what happens!" He admits this led to a few "frayed edges" in level design that, according to fans he’s spoken to, “people love to this day.”

UU’s impact on the game industry was immediately evident in the games that Spector later made in the ‘90s, many of which Neurath worked on as a producer or other high-up role, and he lists modern games, like Weird West, Deathloop, and the upcoming Bioshock follow-up Judas that continue carrying the torch of player-made decisions that are either unexpected or wildly branch a game’s narrative. "That feels so cool," Neurath says, to recognize UU’s imprint in his favorite modern games.

Yet he believes most games, including 2018’s Neurath-led Underworld Ascendant, only go so far to push beyond the industry’s status quo, even within the realm of ambitious immersive sim adventures. Neurath likens the current state of gaming to the 1930s period of filmmaking: "We’ve gotten to ‘talkies,’ but there’s not yet color, that’s what it feels like," he says. While he admits that real-time 3D graphics rendering is advancing at an incredible rate, he doesn’t feel the same about game design and mechanics.

"Gamers may not realize it, but they hunger for that innovation," Neurath says. His current plan at Otherside Entertainment, his latest game studio, is to move the innovative sim genre into a direction that he vaguely calls "player-powered."

His studio’s current design litmus test is to get testers to say, "I didn’t know you could do that," upon completing a level or puzzle, all because the games’ designs revolve around "letting players control the way they solve challenges."

Otherside is also pledging to deliver UU-inspired immersive-sim gameplay in a multiplayer space, though at this point, Neurath has zero details to share on that front. No gameplay or impressions are yet available for the studio’s pair of games with apparent multiplayer modes built in: Thick as Thieves, a multiplayer heist game, and Argos: Riders on the Storm, a Warren Spector-led game that revolves around a "deeply simulated outdoor environment" that may include a significant "butterfly effect" aspect to how the world reacts to players’ choices.

Maybe one day, a Neurath-led game will resemble or surpass the D&D sessions he helmed in college—allowing connected friends to invent and execute bizarre solutions to adventurous challenges. "It’s a very different dynamic" compared to his history in single-player game development, he admits.

"It keeps me engaged to work with awesome teams, having a vision of where we’ll take this. And at least trying. I don’t know if we’re succeeding, but we’re at least trying."

Update: Earlier iterations of this piece incorrectly stated New Hampshire was Neurath's current home state, some of his roles on earlier games were incorrectly attributed, and the dates and timing for UU's pitch process were not accurate. The piece has been corrected.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like