Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How 2DBoy created 2008 indie darling World of Goo, with a little illumination from WiiWare and Steam.

Imagine, if you will: Groundbreaking video games made by small teams. Control schemes that broke the gamepad status quo. Quirky art and stories that pointed to significant political and social statements. All sold via digital storefronts as an alternative to big-box retailers, where such games could top sales charts instead of landing in a discount bin.

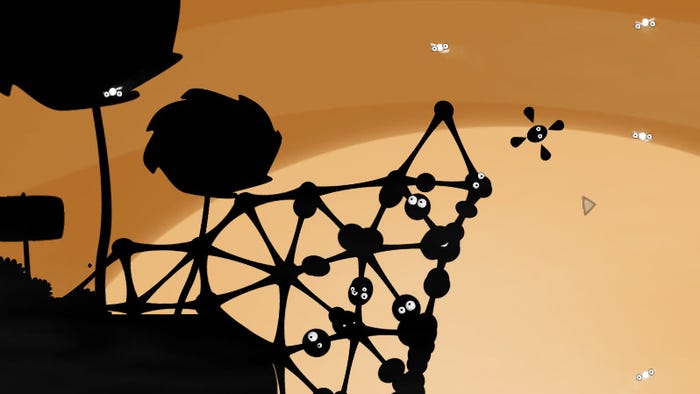

Long before players and developers alike would take those bullet points for granted, one game emerged 15 years ago to combine them into something memorable: World of Goo.

The physics-driven puzzle game revolved around building a series of structures—bridges, towers, pulleys, levers, and more—out of thousands of little, squealing balls of goo. It asked players to do little more than point-and-build, beating Minecraft to a similar spiritual core by two years. Its bizarre plot spoke to the repercussions of mining an unknown substance to generate energy, a full year before the film Avatar showcased its own blockbuster take on the same concept.

And it somehow became one of the biggest games on that year's white-hot Nintendo Wii console, all without a traditional disc version on that system.

On the eve of the retail game's 15th anniversary, WoG co-creator Kyle Gabler and former Nintendo of America digital content head Dan Adelman offer stories about the game's rise from a game-jam experiment to an international sensation. Though be warned: each story comes with the signature self-deprecating wit that made the original game so memorable.

"Do you remember video games in the early 2000s?" Gabler says from his current island home. "They were all about crates."

He describes the variety of drab crates found in 3D games at the time—which he colorfully describes as "brown, tan, or light brown"—as a footnote for the fact that he had "pretty much stopped playing games" by the year 2005. The heyday of his favorite PC adventure games had long passed; "once games turned 3D, I couldn't handle them anymore."

Gabler's gaming fandom originally began with a 286 computer provided by his father, himself a programmer, and he recalls nascent game influences like early Sierra fare and action games made up of ASCII-symbol monsters. "Kids these days will never understand the true terror that is a capital letter H," he says.

The idea of making his own games never came to pass as a child, even though his father encouraged computer use by providing QBasic programming puzzles.

Instead, Gabler dabbled extensively with makeshift toys and construction projects: "water chutes and mazes made out of aluminum foil and cardboard rolls taped to a wall, an articulated hand made out of plastic coat hangers and paper clips, LEGO robots that walk with six legs, or whatever else I could make out of junk I found in the trash." (It's easy to imagine cardboard-and-trash versions of some of World of Goo's boundary-pushing levels, which ask players to transport blobs through murky, swampy environs that sometimes contain blob-slicing razor blades.)

By the time he began attending the University of Virginia for undergrad, Gabler focused his studies on that construction mindset (computer engineering, electrical engineering) with a pinch of music. "I can't sing a correct pitch, and I've got no ability to perform any sort of rhythm," he says when describing his low grades in music classes. "I can click notes into my computer, though."

He found more success in a computer science class with a self-directed twist. Its students were split into teams, each with a mix of artists and engineers, then given an open-ended directive to build animated videos. "The only real goal was to make something as cool as possible, and better than the other teams," Gabler says.

This experimental, self-directed spirit inspired Gabler enough to stay at CMU for a graduate program known as the Entertainment Technology Center (ETC)—which, in a similar spirit, encouraged students to "build cool stuff" that could range from movies to video games to theme park rides.

Gabler hadn't yet figured out what he wanted to be when he grew up, but this program pointed to his compass bearing of "combining art, music, and engineering, then watching little systems come alive and surprise and delight people."

During college, Gabler's lapsed interest in games was rekindled by peculiar titles not typically found on bestseller lists, including PC-exclusive indies like Gish, Nintendo curios like Pikmin, and the PlayStation 2 cult classic Katamari Damacy. "Creative new gameplay was out there," Gabler says. "People were finding it. And we wanted to go searching for it, too."

Weird, inventive video games became a focal point for Gabler's tenure at CMU's ETC, and he began building his own games by combining his engineering mindset, computer programming experience, and extracurricular artistic projects.

He mostly practiced the latter by drawing a daily comic strip for CMU's school paper for three years. "It was bad," he says. "In addition to [my] becoming excellent at failing, I suppose it helped firm up an art style and a particular tone."

That scratchy-ink, big-eyed aesthetic has been preserved in his earliest game prototypes, many of which are still available at Gabler's personal website for downloading and testing. The same can be said for the prototypes' tone, which married comic irreverence with pick-up-and-play simplicity.

One prototype, called Darwin Hill, is a senseless life-cycle simulator that asks players to squish cartoon avatars together to mate, or cull the growing cartoon herd with a click-to-kill sweep that employs a Monty Python-esque murder boot. Just point and click. Another one, Gravity Head, launches its main character around the screen via a magnetism system, and players win the game by slamming their character's oversized head into a Rube Goldberg machine of flower pollination steps. Again, just point and click.

The prototypes were borne out of an idea Gabler and a few classmates invented together, as ETC students were expected to pitch and execute a final-semester project as a group. They proposed the "Experimental Gameplay Project," which would require each participant to build a different playable video game prototype from scratch every week of the semester. In other words, they convinced their professors to let them run a months-long game jam. (In the years since, game jams have become more common in collegiate game development programs.)

Gabler created an animated video to pitch the project to his supervisors, which he provided to Game Developer. It features shoddy, Flash-animated versions of each of the three pitching students (Gabler, Kyle Gray, Shalin Shodhan) dumping black blobs onto an assembly line. In a prescient twist, the blobs are eventually sucked into a series of ominous tubes.

Each week, the ETC's contributors uploaded their playable games to a public website, and Gabler is unsure how it received wider attention beyond fellow students and friends. Gabler notes that there was no way to quickly share video footage of the prototypes, as YouTube didn't exist, so people were downloading and installing unsigned code from an amateur website.

Bad security practices aside, fans began to accumulate, particularly for a prototype called Tower of Goo. "Right away, [ToG] started getting bizarre amounts of attention," Gabler says. It was a one-level proof of concept with a goopy physics system, and it asked players to simply build a tower by pointing a mouse to pick up and place balls of goo. Its original "readme" document confirms that the ETC's theme for that week—the ETC's second week—was to "make something with springs."

ToG largely resembles the retail game that eventually launched three years later, as it asks players to build a solid structure whose bearing points—small, black balls of goo—automatically connect together with magically appearing sinewy tissue. A built-in physics system dictates how well, or poorly, the combined structure stays in place. If a player doesn't carefully mind the tower's total weight, or the springiness of each connection, the whole thing will topple over.

The initial prototype allowed players to build a tower to a specific maximum height, and Gabler immediately received feedback from players: Can we build the tower higher? Gabler patched the prototype to remove the limitation (again, without charging downloaders a penny), and players responded by posting proof of their ridiculously tall creations to message boards.

"With playtests, it's always a good sign if the player is talking more about their own performance, and not about the thing you've built," Gabler says. "That tended to be the case with Tower of Goo. It was nothing fancy, just barely functional art, but the gameplay was easy to understand and fun to play with, so nobody cared what it looked like."

Gabler's final grad school internship was at EA's California HQ, and shortly after, EA hired him full-time for an ETC-like game development role. (Fun fact: Before this stint, Gabler also interned with the musician responsible for Seinfeld's opening theme.) He joined an EA team whose job was to build prototypes, then test and refine pre-production systems and mechanics before they found their way to larger game-dev projects.

He describes his time at EA as "a dream job in retrospect," since it resembled the zero-boundary experimentation he relished at CMU. But after one year, he tired of his work not gelling into a formal game that he had any stakes in.

Other developers were leaving bigger publishers and starting their own small studios. Maybe he could, too. (In describing his decision to leave, Gabler also recalls a pair of uncomfortable scenarios within EA's offices. In one case, an executive producer took a snack from Gabler's desk, ate it in front of him, then handed him a single dollar as payment for the food.

Another involved a different executive producer who, several times, "put his large, hairy hands on my shoulders, rubbed me, and asked, ‘You makin' me rich today?'" Gabler clarifies that "everyone else [at EA] was pretty great!")

He co-founded his new company, 2DBoy, with Ron Carmel, an engineer who had been at a different EA subdivision, the Pogo casual games group. (Ron Carmel did not respond to Game Developer's requests to talk about World of Goo.)

Gabler says the duo was introduced to each other by a mutual friend at Pogo who "knew we both wanted to start a business." That mutual friend, Jim Greer, would go on to co-found the casual gaming portal Kongregate shortly after, and Gabler admits that during that lean period of his life, he and his cat Madonna "lived and slept" in Kongregate's back office for his new company's first year. (Gabler also admits that he saved money by using the same cat shampoo as Madonna.)

2DBoy began life in the form of an afternoon-long, two-person game jam, and the resulting prototype, dubbed Fisty, revolved around a "large, sad frog that you'd squeeze to make it shoot out a physically simulated tongue and catch stuff." The development process was more fun than the game, Gabler says, and while the prototype went into a dust bin, Fisty the Frog lived on as a prominent character in World of Goo.

The studio admittedly began without a formal plan or design document beyond agreeing to make a unique game. A few prototypes came and went, including a resource-management sim where players controlled a moving tree. Then Gabler was sent a video from a former CMU classmate that featured a Tower of Goo clone coded for the Pocket PC platform. "If my back catalog is going to get mined, I'm going to mine it first!" Gabler says.

And with that, 2DBoy got to work on its own "clone" of Tower of Goo. The first level was identical to the prototype: build a tower that reaches a certain height ("20 meters") without falling over. "What should level 2 be?" Gabler rhetorically asks, rewinding to 2DBoy's original design process. "Build a tower 30 meters high? Then level 3: 35 meters high and maybe there's wind? That game would have been terrible."

The duo's design and experimentation process accelerated once Gabler and Carmel settled into a "left brain, right brain" delineation of labor, with Gabler focusing on art, music, and general design, and Carmel focusing on programming, engineering, and business.

This was as close as the company ever got to having a "producer," and the division of labor paved the way for the game's other elements to fall into place. Level design ideas eventually emerged, and these in many ways reflected Gabler's childhood junk-drawer engineering efforts.

2DBoy created new blob types (floaty balloons, anchoring skulls, sticky blobs, exploding blobs, and so on). And they asked players to build and guide their universe of blobs up, over, around, and through levels that became more creative as the months went on. Gabler admitted in a 2008 interview that some of the level design wasn't finalized until one month before the game launched.

By having friends test the game's earliest prototypes, the duo also realized that a sense of place, plot, and structure helped. Early players had questions on how to solve certain puzzles and learn how the game works, but instead of merely dropping tutorial messaging into the game, Gabler imagined an in-game character doing so. "Who's writing the signs?" he asks himself. "Some sort of Sign Painter, probably."

This idea, inspired by the Game Boy classic The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening, led to an omnipresent antagonist. That character then fed into a larger plot of exactly what the goo balls were and why players were funneling them into tubes, which led to the creation of a cast of characters and ridiculously massive world-affecting stakes.

Gabler admits that his business acumen began and ended with buying a few books on the topic of starting a business. He admires his naivete in hindsight: "I'm glad I was kind of clueless. Otherwise, I probably wouldn't have quit [the job at EA] and started a business with no plan." His earliest compass bearing was to follow the money that had been landing in the casual games market that Carmel had witnessed firsthand as part of Pogo. The duo believed that market might be "the best fit for the experimental, non-3D, colorful games I wanted to make."

In retrospect, Gabler is thankful that 2DBoy's first game didn't sign with any of that era's casual gaming portals. He suggests such deals would have required surrendering as much as 70 percent of each sale, compared to the 18-30 percent taken by modern digital-download storefronts. Casual storefronts "would also require you add their logo to your game," Gabler says. "I'm not sure which was worse."

At the time, however, that meant no up-front infusion of cash from a publisher, which meant the duo largely lived off of money they'd made during their brief time at EA—and Gabler had more debt than cash, which at the time he described as "negative $30,000."

The duo cut costs primarily by not investing in office space, instead mostly working at cafes and coffee shops in the Bay Area. They also waited until closer to the game's shipment to bring on outside help in programming, quality assurance, and language translations. Gabler's musical proficiency had improved since struggling in college courses, so he was the sole composer and arranger for WoG's music and sound effects, while Carmel led 2DBoy's business management. (Again, left brain, right brain delineation.)

Due in part to their sour attitude about casual gaming portals, Gabler and Carmel were convinced that having a boxed game launch was the right path. ("It was a different world back then," Gabler says. "How would I explain to my parents I was selling an imaginary game you couldn't hold?") Eventually, they connected with a traditional publisher to print and distribute a PC version at brick-and-mortar stores. Before that, however, the duo made an unlikely connection.

Dan Adelman had joined Nintendo of America one year before Wii's retail launch and eventually led the company's earliest digital distribution plans in the modern era (not to be confused with Japan-exclusive download services like BS Satellaview and Randnet). A retro-minded digital download service dubbed Virtual Console arrived on Wii shortly after its 2006 launch, and Adelman tells Game Developer that this service was meant to "open up to new games" at some point.

Before this shop had adopted the name WiiWare, Adelman went to his bosses at Nintendo with a pitch: the Wii should have a games-download store with gameplay innovation at its forefront. "Games were, in my opinion, getting quite formulaic and boring," Adelman says (echoing Gabler, though without any jokes about crates).

He describes the issues he saw in that era's industry with risk-averse publishers, saying they were "reluctant to experiment with new gameplay ideas." A downloadable games shop would limit those risks, he thought.

The biggest fight he had in building WiiWare was a disagreement with Nintendo of Japan President Satoru Iwata. Adelman believed that the service would benefit from tightly controlled curation: "we [at Nintendo] would select games based on what we wanted the service to be," he says. He otherwise feared a wave of "shovelware" on the service.

Yet Iwata made the executive decision to forgo such a restriction. Adelman explains that Iwata "harbored a lot of regrets about the third-party approval process during the Nintendo 64 era that led to Nintendo missing out on some great games and alienating publisher partners at the same time."

Still, Adelman was responsible for attracting games and game makers alike to a brand-new, paradigm-busting storefront, and he couldn't draw from a bustling indie marketplace, thanks to services like Xbox Live Arcade and Steam being quite nascent.

His first thought was to appeal to casual game portal owners (Big Fish, Real Arcade, Yahoo! Games) and casual-friendly studios like PopCap and Gamelab. Adelman pitched these companies on making unique fare for this new Wii-exclusive storefront, but left disappointed: "most of those companies just wanted to dump their existing casual games catalog onto the system."

Adelman, in his beleaguered search for unique and experimental gameplay, typed experimentalgameplay.com into a web browser. Gabler and his fellow CMU students had registered that very domain to host their years-old prototypes. Adelman began downloading and playing them all, and he recalls their concepts and mechanics to this day without having to re-download them. "All of my favorite prototypes were made by the same person," Adelman admits: Kyle Gabler.

The duo soon began corresponding over email, and Adelman made a hard sell: come to WiiWare, and make a new game. Gabler reluctantly mentioned that he was already working on a fuller version of Tower of Goo. "To be honest, at the time I didn't see how it could be a full game," Adelman says. "But I also recognized that Kyle was a far more creative game designer than I was, so I decided to trust his vision."

Gabler says that 2DBoy needed "a bunch of conversations" to be convinced of WiiWare's potential. Adelman's persistence did the trick, and 2DBoy saw the new service's potential benefits. Skipping a disc for a console port "was a lot simpler for various technical reasons," Gabler says.

They also liked that the royalty rate for each sold copy was better than that era's boxed-copy equivalent, without distributors or other parties taking a cut. And they had internal champions at a company they respected—not just Adelman, but a few key names at Nintendo's Kyoto headquarters.

"One of our happiest moments was when Iwata and Miyamoto played chapter one, liked it, and said, ‘Hey, let's make this get on Nintendo,'" Gabler told Game Developer in a 2008 interview. "Childhood heroes playing your game—it was a head-spinning moment for both of us." (In the years since, Gabler admits forgetting that anecdote; he had to be reminded by re-reading the interview.)

Nintendo otherwise served as a quiet and productive partner, in terms of staying "hands off" with the game's content and aesthetic, yet simultaneously assisting with last-minute rushes. Gabler says the biggest issue was WiiWare's file size limit of 40 MB, which was comparable to Xbox Live Arcade's earliest package-size limitations.

2DBoy found that fans didn't complain about heavy compression applied to World of Goo's background images (which were intentionally blurred) or music (with the team manually adjusting each song's bitrate until they found the sweet spot of unnoticeable distortion). To this day, Adelman remains impressed that 2DBoy figured out how to pack so much Goo into so few MB.

On October 13, 2008, World of Goo launched on Nintendo's WiiWare service and Windows PC. (A Mac port arrived one month later, with a Linux version following in early 2009.) The game was riding a moderate hype wave thanks to positive previews and a few notable victories at that year's Independent Games Festival (IGF) Awards. Nintendo of Japan had been so hot about the game's potential that it published the game's Japanese port. Things seemed good.

For small development teams, Steam's internal tools were a revelation in 2008, as they offered the kind of real-time sales data normally obscured by larger distributors. 2DBoy also sold the game's downloadable PC version via a button on its home page, so it could track that data as well.

For World of Goo, however, the initial response was grim. "This is like throwing a party and nobody shows up," Carmel said to Gabler as they reviewed the game's day-one Steam sales figures. A few days later, after hearing that the WiiWare version was selling "okay but not great," Gabler took a phone call from an old friend offering congratulations about the game's launch. "It felt horrible," Gabler recalls. "It felt wrong being congratulated for something I was feeling pretty bad about."

Positive reviews were pouring in from traditional outlets, and World of Goo enjoyed serious WiiWare visibility upon its debut, with only three other games launching on the service that week: a trippy entry from Nintendo's experimental Art Style series, and a pair of 16-bit Virtual Console games. Something wasn't adding up.

Gabler's most telling experience came at a Target store in the Bay Area where World of Goo's boxed PC version had been stocked. He overheard a woman being handed a box by a child, to which she responded, "World of…Goo? I don't think so." She put the box back where the child had found it.

"We thought maybe people just weren't sure what this strange Goo game was about or how it worked," Gabler says. 2DBoy tried to rectify that with an idea the team hadn't prioritized in the scramble to ship the game on WiiWare and PC simultaneously: a free, playable demo on PC. Gabler admits having no idea how much that demo impacted the game's slow rise in sales from that point on; "our best guess is word of mouth finally started spreading," he admits.

World of Goo also enjoyed a hefty sales bump on Wii due to its inclusion on a promotional WiiConnect24 message, which Nintendo sent to all console owners who opted in. That World of Goo message appeared "around Christmas," Gabler says, so it would have been seen by many new Wii owners with a digital download gift card and questions about how WiiWare works.

"Sales continued building and building," Gabler says—and the game's long tail of sales was helped to some extent by it getting a free WiiWare demo in November 2009 (one of only five games to enjoy such a promotional spot on WiiWare) and a spot in the very first Humble Bundle sales promotion (which Carmel pushed for).

While nobody involved is able to offer sales specifics, Adelman confirms that World of Goo appeared in WiiWare's weekly best-selling games list for "over a year after its launch."

Many of Kyle Gabler's hindsight statements about World of Goo are delightfully odd. They reflect a softening attitude about the 2008 game's dark-comedy highlights, which he openly admits to: "There was a brewing anxiety throughout World of Goo about people and places getting older," he says. "I suppose if one thing is true, 15 years later: we've all gotten older too."

In the same breath, he finds humor in his own softening perspective on one of the game's themes. "I hope I didn't come down too hard on consumerism," he says. "I love consumerism! I love buying stuff. Consumerism is the reason cool stuff gets built—and gets cheaper over time. If no one bought stuff, I wouldn't be able to get better and faster computer equipment every few years. And I love computer equipment."

He admits feeling "silly when he reflects on how on-the-nose some of the game's meta-commentary turned out. "The goo balls stare up into the sky and wonder what's up there. Pure little balls of curiosity and wonder. Meanwhile, a vast international corporation with a global pipe network slurps up goo balls from every corner of the globe—processing them, packaging them, and selling the product to customers as food, oil, and beauty cream. It's not one-to-one, but when you're a young game developer who earnestly wants to make something beautiful, you can feel an awful lot like those curious goo balls."

Yet even his silliest answers align with the point of the game, which remains as enchanting and captivating now as it did during its launch. "It's a silly game about goo balls that's also somehow about beauty, progress, surveillance, and that feeling of exploring a big, scary world that doesn't care about you," Gabler says. "There's a lot of stuff sloshing around in there, and the game [is] just kinda has fun without trying to convince anyone of anything."

He mentions apprehension about "serious" content in his games, which he explains using the present tense: "I don't feel like I've earned [serious moments] unless I also pair them with something silly and try to make the player laugh."

As if to prove his point, when asked whether he identifies with his game's 2008-era commentary on vanity, he replies, "Well, I'm incredibly vain, so I feel good about that!"

Shortly after World of Goo's launch, Gabler and Carmel went their separate ways—a possibility that was baked into 2DBoy's original plan. "Neither of us knew what we were doing, and neither of us knew if we'd be able to make even one game and sell it," Gabler says. Upon the game's completion, the duo was forced to ask each other, "We did it! Now what do we do?"

The dissolution wasn't immediate, with Carmel publicly suggesting a possible 2DBoy follow-up game in an early 2009 presentation, but Carmel eventually went on to co-found the game development investment group Indie Fund, while Gabler moved on in 2009 to found a new game-making studio, Tomorrow Corporation, with two other ex-EA developers.

Gabler calls 2DBoy "a lifestyle project that gives us freedom." He describes his current game studio in a similar way, and that's one reason why his current game project, dubbed Welcome to the Information Superhighway, has remained hidden from public view since its announcement in 2018. Gabler relishes the ability to freely adjust his schedule and take on projects for his home or personal life, which he admits includes "building a way to live off the grid" on his current island home.

Unprompted, he describes an energy-usage monitor that tracks his entire property. "'That microwave is using 1200 watts! Look at my graph!' is something I have shouted," he admits.

There's a World of Goo-like metaphor for how Gabler has lived in the years since its launch. Personal resources can be pulled together to build temporary, useful structures, with additional, excited goo balls squealing and cooing as they traverse the freshly drawn paths, only to be torn down and reassembled as appropriate whenever it's time to make something new.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like