Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

One of the most iconoclastic developers of the 1990s disappeared this week, and I share my memories of him and his games.

I found out yesterday that Kenji Eno had died.

These days, a lot of people don't really know who he was, and that's understandable, if sad. Eno rose to fame in 1996, and the last major console game his studio, Warp, developed was released in 2000: the flawed but fascinating D2, for the Sega Dreamcast. Though he developed games both before and after those years, that was when he burned brightest -- a very short period, and a long time ago.

There's an article to be written about Eno's career -- he deserves it, and it needs to be done. But that will take time. Right now, I want to talk about what Eno's games meant to me personally; I want to talk about what they did mean -- and could have meant -- to the industry; and I want to talk about what I understood of the man himself.

In 1995, his studio, Warp, released the original D for the 3DO (and later the PlayStation and Sega Saturn, with these releases making it to the West in 1996.) From the moment it first showed up as tiny, blurry screenshots in magazines prior to its release, it was a fascinating game. It became a cult hit despite its limited interactivity -- it was purely full motion video with no real-time elements -- because of its disturbing mood and plot twist.

D protagonist Laura Harris

The story revolves around Laura Harris, a college student who is called from San Francisco to Los Angeles when her father, a doctor, murders his patients and barricades himself in the hospital. Laura ends up going on a strange journey into an alternate reality to try and understand what's happened to her father.

As a game, D is not that great, but as a creative statement of intent, it's bold. When I played it in 1996, I was let down by my huge expectations, yet still incredibly optimistic about Warp as a studio. It was clear to me that this was a direction that games could, and should, go. At 19 years old, in 1996, I was watching cerebral, disquieting movies directed by people like David Lynch and David Cronenberg, and that kind of subject matter just wasn't available in games. The promise of a new generation -- at that time with the PlayStation and Saturn -- was that things could move forward creatively in a fresh way.

Kenji Eno will always be remembered for D. Partially that's because he never realized his true potential as a game creator -- which is what makes his death so utterly tragic. That doesn't mean, however, that his other games aren't worth exploring.

Eno made two more games featuring Laura, his digital actress, as a protagonist, and they form a loose trilogy in creative intent, if not in terms of continuity. Enemy Zero and D2 both follow the arc Eno began to trace with D.

After D became a major hit in Japan, Eno's star began to rise; but he was unhappy with Sony, and decided to hitch his star to Sega's wagon. His next game, Enemy Zero, was a Sega Saturn exclusive, which severely impacted its reach, if not its ambition.

Enemy Zero is an adventure game with invisible enemies. It stars Laura Lewis (same "actress" but different character than D's Laura Harris) as one of a few people trapped on a space station menaced by invisible enemies.

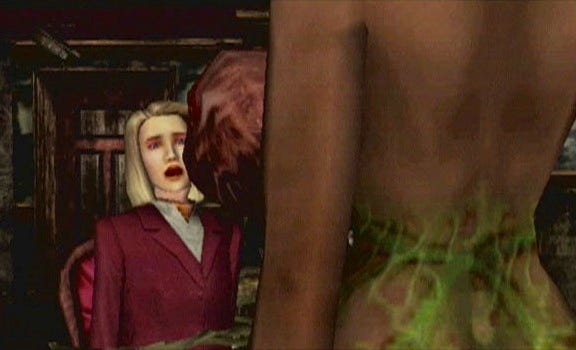

Laura speaks to Kimberly on the space station AKI. Kimberly would also reappear in D2 as another of Eno's digital actresses. Taken from an amazing set of high-res Enemy Zero stills. Picture inserted into this blog post to troll Chris Hecker.

The exploration and story segments play much like D -- first person, full motion video -- but there are real-time parts, too, however, and these are where the real weirdness and out-of-the-box thinking appears. They're first person, disorienting, unpleasant, difficult. The enemies are invisible -- literally invisible -- and you have to try to ping for them with sound, it's best to avoid them but sometimes you can't, and then you have to try and take them down with a measly little gun.

It's harrowing -- almost painfully challenging. In fact, at the time, I loved the game, but I eventually reached a point where I found it impossible to progress -- I remember really sweating over this bit and gave up in extreme frustration, without finishing the game, which I had really been enjoying up till then. From this, I got the sense that Eno wasn't afraid to make his games completely inaccessible if that was his vision -- an inability to compromise.

Enemy Zero was followed up by D2, for the Dreamcast, continuing his relationship with Sega. I remember trying to watch the livestream of the event where he announced the game in 1999 at the offices of a local ISP where I worked at the time; even with that kind of connection, it was impossible to watch the postage-stamp sized video hosted in Japan.

Throughout this phase of his career, Kenji Eno's work had some kind of magnetic pull with me, despite the fact that I always found it flawed -- I still felt like this was the direction (or at least a direction) that things should be going, and they still weren't by and large going that way. Enemy Zero came out not long after Final Fantasy VII and Resident Evil, but it was more personal, more nuanced from a storytelling perspective.

It's interesting to reflect on the fact that while far too many games are influenced by Aliens, very few seem to be really influenced by the first movie in that series, and really put you in a position of powerlessness, or concentrate on the human drama. That's what Enemy Zero, with its spaceship full of desperate people and invisible enemies, attempted to do. Give me Enemy Zero over Prometheus any day.

Even if I didn't get all he had to give, Enemy Zero left me believing, as before, that Eno wanted to do more with games than was possible at the time. And that's the reason that Kenji Eno's games had such a pull for me, despite the fact that they'd never totally clicked, either.

When D2 was announced for the Panasonic M2, the successor to the 3DO, I obsessed over the screenshots and considered whether to buy the system, despite my borderline total disinterest in its predecessor. The game was planned as a direct (if circuitous) sequel to D -- it starred Laura's kidnapped unborn son, aged to a teenager, and sent back in time to medieval Europe -- and was going to be Warp's first real-time 3D adventure game.

The M2 was cancelled, and so was this version of D2. (You can find footage of it on YouTube, though.)

When the game reemerged, for the Dreamcast, it had been recast as a horror adventure RPG in the snowy interior of Canada. Laura -- this time Laura Parton -- slogged through the snow, fighting grotesque mutations. It's an unusual game -- you actually have random encounters with the enemies, but they're action-based; the adventure parts are much like D and Enemy Zero, but they're in real-time. As ever, there's a lot of (disturbing) dialogue and scenes -- notably, one of a tentacle monster orally violating a female character, was censored for the U.S. release of the game.

Even though I didn't end up finishing D2 either (I played a bunch of the Japanese version, but put it aside when the U.S. version, which I never ended up playing, was announced) I just remember thinking that Warp was moving onto the right track -- the game had solid, approachable gameplay, fantastic mood, a gorgeous soundtrack (composed by Eno, notably) and further explored the macabre aesthetic Eno found fascinating.

And then... nothing.

Eno stopped developing games. In fact, he wouldn't release a game again until 2009, with You, Me & the Cubes, for WiiWare -- which next to nobody noticed, for one reason and another. It's recognizably Eno thanks to its beautiful sound design, if nothing else.

There were rumors that Eno had a more elaborate game in the works with Nintendo, but, well, they never amounted to anything -- except further rumors that Eno had abandoned the project after falling out with the publisher.

And now, they never will. No projects will.

With D2, Eno came close -- in my opinion, anyway -- to realizing the total aesthetic he had aimed for with D and Enemy Zero. He never quite got the the balance (or style) of gameplay and storytelling right, but he's hardly alone in that.

Eno seemed to be establishing a style, an aesthetic -- he was developing as an artist, trying new things but staying true to himself, and then he simply stopped. As great as the PlayStation and Dreamcast were -- so full of fantastic games -- Eno stood out. Thus, his absence was palpable.

Like many game developers, Eno was in thrall to Hollywood. You can easily draw comparisons to Alien or The Thing, but to do so without consideration isn't instructive. He was probably also influenced by David Lynch -- who looms over Japanese pop culture in a way he utterly doesn't in the U.S. (think Silent Hill and Deadly Premonition, to name two obvious examples.) After all, Eno's heroine is a blonde caucasian woman named Laura, just like Laura Palmer. But the important aspect of Eno's interest in film is that he didn't use his influences as a stylistic end point; he explored via games what the moods that these stories evoked should mean for players.

The way I look at Kenji Eno is basically that he was David Cage before David Cage was -- but more iconoclastic, more experimental, and with less posturing.

If you look back on the Japanese console scene of the 1990s, it was going in directions that got utterly cut off when the PlayStation 2 came out -- on the PlayStation and Dreamcast, in particular, developers were trying lots of new things, and had a cultural awareness and flair for experimentation that we're only now getting back to thanks to the rise of a thriving indie scene.

Back then, the big Japanese publishers were more prolific than they are now, and regularly made better, more groundbreaking games; even the traditional stuff was much savvier and more original. Things calcified to "business as usual" during the PS2 generation, and a lot of that died away totally, and it's gone now.

Because of that, and because of the rise of Western developers who are just starting to learn the things he'd figured out in the 1990s, I'd always hoped that Kenji Eno would come back and show the industry what he was capable of. And that, obviously, isn't going to happen -- can't happen, now. And that's really, really sad.

I'm glad I got to meet him, once, in 2006, when he attended E3 for some meetings. He was a friendly guy in person, unassuming, relaxing, unconcerned with his image. And though it's not as though I thought about him, or what could have been, very frequently anymore, I'll miss him. The game industry lost something important when Kenji Eno left it, and lost more when he died.

The author with Kenji Eno at E3 2006

Essential Kenji Eno reading:

1UP's 2008 interview, his first in almost a decade, conducted by Shane Bettenahusen (his biggest fan that I know) and James Mielke

Hardcore Gaming 101's History of Warp

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like