Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

This is a collection of articles on narrative, narrative atoms and story telling that I have put together as a new chapter for my potentially upcoming expansion to Even Ninja Monkeys Like to Play

This is a collection of articles on narrative, narrative atoms and story telling that I have put together as a new chapter for my potentially upcoming expansion to Even Ninja Monkeys Like to Play

Whenever I speak to people in the circles within which I hang out, one of the things I keep hearing is story and narrative. “You have to tell your story”, “What is the narrative?”, what is the companies story”. To be honest, it drives me a little nuts, but that’s by the by. The fact is, these are important things to consider. One of the things that have got me thinking, is what is the difference between story and narrative?

Story seems to have quite a few definitions. According to the Oxford dictionary, it is:

an account of imaginary or real people and events told for entertainment

a report of an item of news in a newspaper, magazine, or broadcast

an account of past events in someone’s life or in the development of something

the commercial prospects or circumstances of a particular company

Whilst narrative is defined as:

a spoken or written account of connected events; a story:

So really, story and narrative are pretty much the same things! For me, the most important definition from the above lists for gamification is number 3 “an account of past events in someone’s life or in the development of something”. The way I look at both is that the story contains a start, a middle and an end. A narrative is more real time, it describes events as they are happening from the perspective of the person they are happening to. If you consider a game, the narrative would be the way events unfold as you play. The story will include the backstory and the ongoing plot of the game. That being the case, the story would be the same for each player, whereas the narrative would potentially be unique to each one.

How does this relate to gamification? Well, on the one hand, you could consider that everyone has a story, they have a history and they have things happening to them right now. All of this goes influences who they are and who they may be in the future. In gamification, we are often looking at influencing or changing behaviour, knowing the story of each person can help inform us how best to engage with and motivate them.

You could look at it even more literally though and create a story and so a narrative for each user to engage with whilst they use your system. This could be especially useful during the onboarding or scaffolding phases. Take your users through a story, preferably one that changes based on the choices they make and how they wish to go through it. Give them what they need through completing parts of the story. Doing it this way, when done well, will have far more impact on them than giving them points for doing things. The sense of purpose that a story can give is very powerful – even if it is more a short story rather than an epic!

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but a good story is worth a thousand instruction manuals.

Now that we know a bit more about what narratives are, I want to dive deeper into building narratives and stories, starting with the concept of Narrative atoms.

Narrative atoms are small units of narrative or story that can, within the context of the overall narrative, stand alone. That does not mean they need to be completely self-explanatory, just sit comfortably on their own.

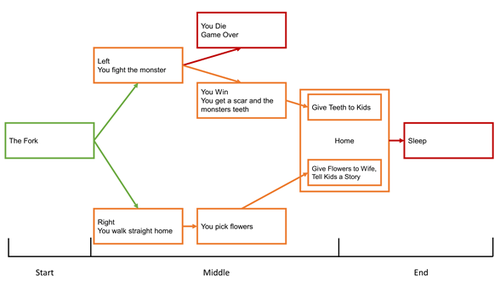

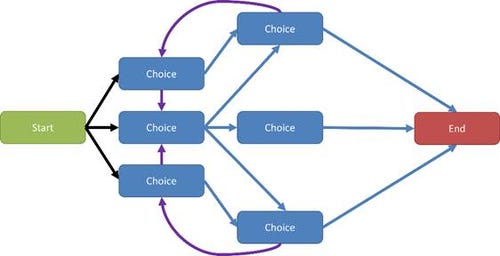

Figure 1 Narrative Atoms

In a standard linear story, each atom would be placed sequentially, so their ability to stand alone is less important. However, in many games narrative bends and twists and turns in a non-linear way. For that to work, for a story to makes sense as it jumps from A to C to G to B and back again, each section, each narrative atom must be able to hold its own without the need every other atom to support it.

Take a scenario where a game has more than one option for what you can do after the first scene. You have a choice of going left or right.

After that, you have more choices and more, but all the while the narrative needs to keep making sense. More than that, it all needs to conclude and not leave the player wondering what the hell has happened!

At their most basic, stories have just three parts. A start, a middle and an end. In traditional media that is straightforward. There are many ideas out there on how to write stories, Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey / Monomyth 1 gets a lot of attention. I also rather like Kurt Vonnegut concept of Story Shapes 2.

For my purposes when designing simple stories in gamification scenarios I use two simple (and I do mean simple) variations of what I call the Soap Hero’s Journey.

The simplest version has four phases. The Calling, The Challenge, The Transformation and The Resolution. The second version adds The Twist after The Transformation. I’ll go into more detail later, but suffice to say these are not much different from the simple concept of a story having a start a middle and an end!

Back to narrative atoms. Each atom should have a start a middle and an end in its own right. This is how they are able to stand on their own if needed. As I say, in a linear story this is less important, however, if you are creating a branching narrative it is essential.

The first thing you need to know in a non-linear narrative is obvious, how it will begin. This sounds simple, but you could have multiple starting points for your game’s character or characters. After that, you will certainly have many parts to the middle, some the player will see and some the player might not on the first play through. Finally, there may well be multiple places for the story to end.

As the player will be able to navigate through the story in multiple ways, you have to know how each branch fits together and how each choice the player makes can affect the outcome of their story.

This is where considering narrative atoms can help. If each atom has its own start, middle and end it is easier to jump in and out of them at will. As you knit the story together, you can pass events from each atom onto the next one, ensuring that character and plot progression or alteration is kept consistent, without having to create vast quantities of alternative narrative to account for every choice.

Start

You are in the woods. Ahead of you, there is a fork in the road. You can go left or right. What do you want to do?

Go Left

At the fork in the forest, you take the left turn. Ahead of you is a giant monster. It reminds you of ones you used to read about as a child. This is what you had prepared for and you know what you must do. As the beast charges at you, you remember that there is a weak spot on its back, just between its shoulders. All you have to do is get your sword in there.

You win

The fight with the monster will go down in history and the scar that it has left on your cheek will only add to the legend. You are able to get behind the beast, finding higher ground to attack the weak spot between its shoulders. Once you are sure it was dead, you take its giant teeth as a trophy and continue on the path towards home.

You lose

The fight with the monster will go down in history, but sadly you will be but a footnote. You are able to get behind the beast, finding higher ground to attack the weak spot between its shoulders, you lunch just a moment too late and are caught by the beast. The last thing you hear is the snap of your neck.

Go Right

At the fork in the forest, you take the right turn. The sun is shining and the birds are singing in the trees. As you walk, you pick flowers from the path and collect them in your bag. After several hours of blissful and uneventful travel, you reach home.

Home

After your journey, you are elated to be home. Your family is waiting to see you, your children eager to see what you have bought them from your travels.

If you fought the beast

The fight with the monster has taken its toll and your wife is concerned about your cheek, but before she can speak about it, you produce the monster’s teeth from your bag and proudly hand them to the children.

If you didn’t fight the beast

You turn to your wife and offer her the flowers from your bag, now tied into a beautiful bouquet. For the children, you sit them down to tell them a wonderful story of a hero who must fight a monster in the forest.

With your children happy and your wife just pleased to have you home, you settle in by the fire and sleep peacefully.

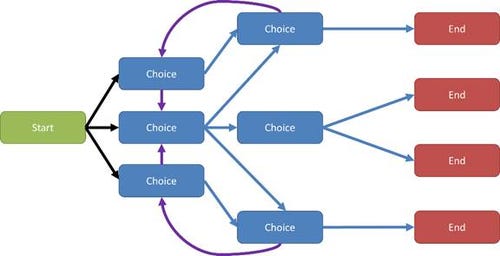

Figure 2 Boy Meets Monster, Boy Kills Monster

Each section of the story can stand up on its own, given the context. Each atom explains itself and resolves itself whilst being able to bond with the next part. Of course, this is very simple and most non-linear narratives will require each atom to have multiple bonding points, where the story can link to other atoms whilst still making sense, passing on critical information to change key parts of the next atom.

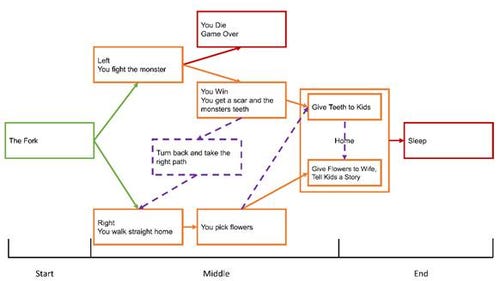

Figure 3 Boy Meets Monster, Boy Kills Monster Again

For instance, in our little story, if you fight the monster, you could choose to allow the player to then turn back and take the path where they pick flowers. This would add an extra bond to the monster fight, and also allow the player to experience both parts of the potential endings – giving the wife flowers and the children the teeth.

The key is to make sure that each atom can be as self-sufficient in the narrative as possible and that you only have to pass essential information to the next atom to make the story continue to be coherent.

Her Story is the fabulous creation of Sam Barlow. You take the role of investigator, reviewing a police archive of video footage of a British woman accused of murder. You can access the footage in any order you like, gleaning more clues and information with every video you watch. Sometimes the videos will not make sense until you find the video that came before it, others give you all you need in just a few seconds of footage. The joy is discovering how the story fits together, jumping back and forward through the timeline. New snippets of information give you new ideas on what to search in the archive, leading to many "Ahahaa" moments.

The second is a well-loved game, Gone Home from The Fullbright Company which it is a brilliant lesson in narrative design. Similar to Her Story, Gone Home tells the story in small atoms - fragments of what happened in the house you are exploring. Each scrap of paper, audio recording or newspaper clipping adds something to the story.

Both of these experiences, whilst seemingly disjointed, eventually build up a deep and fascinating narrative. Each atom may not seem to be relevant but may combine with another atom to unlock a key plot element or answer to a puzzle. In each case, you do not necessarily have to see everything to complete the game, but to fully understand everything it does help! You also don't have to see everything in chronological order, but it can help ;)

The lesson is that using narrative atoms can help you create incredibly deep narrative experiences that don't have to follow any particular path, giving people that opportunity to discover the whole picture in their own unique way!

Heavy Rain. That was the name of the game that first made me understand that meaningful choices could take a game to new levels of immersiveness.

If you have never heard of it, Heavy Rain was a PS3 exclusive in 2010 from game makers Quantic Dream. You played the roles of several people through a convoluted mystery. There was the father who had lost his son, the private eye, the reporter and the FBI agent all linked to the mysterious Origami Killer. As the story unfolds, you have to decide how each character acts, how they handle conversations and what choices they make.

This was the key. The choices all had consequences. Make the wrong one, and a character could die. Your choices dictate what parts of the story you saw and how it ended. Every decision was critical to how your game played out. In fact, in an interview, David Cage the director of the game said that he wanted people to only ever play the game once. That way their experience would be unique. When they discussed it with others, they would then find out there were whole sections of the game that they had never seen – so each person’s playthrough would be theirs.

More recently games like Walking Dead and The Wolf Among Us from TellTale Games have taken this approach to choices within their games. Each choice you make feels like there is weight behind it, they feel like they have consequences.

My experience is that people like to feel their choices have a meaning, they also like to feel that they have choices in the first place. When you look at my User Types or the RAMP framework, Autonomy is one of the key motivators – especially for the Free Spirit type. That does not mean they are the only ones who are motivated by some level of autonomy. If we feel that we have no freedom to move, to choose and be in control of our own destiny – we feel constrained and disengaged from the experience.

When creating your gamified or game based solution you should try to build meaningful choices in. The ideal is that choices change the outcomes of the experience, but even if they just feel as though they have meaning that can be enough.

If you have a game-like solution, allow users to choose their own way to play the game. Let them solve problems in multiple ways. In narratives, allow them to choose how to answer questions or where they go next in the narrative (that’s why I love choose your own adventure style narratives!). In pure gamification, allow users to choose what they do next. If it is a learning experience, let them make their own decisions about what they learn next.

If that level of freedom is not possible, then you should, at least, make it feel like there are choices and that they affect outcomes. The trick there is to make sure they can’t go back and repeat their actions – thus discovering their original choice did not affect the outcome after all. I have seen this in a lot of games. It feels like you are making decisions that change how the game will play, but then on replays, it turns out that the game would always funnel you down to the same conclusion no matter how you played!

Combining the concepts of narrative atoms and meaningful choice, we begin to explore narrative choice architecture, where each choice makes a real difference or at least appears to. Here I discuss a few different approaches.

When you sit down with a book, you start at the start and then read every page until you get to the end (unless it is a choose your own adventure…). The only choice the reader gets is whether or not to start the book and read it all the way through.

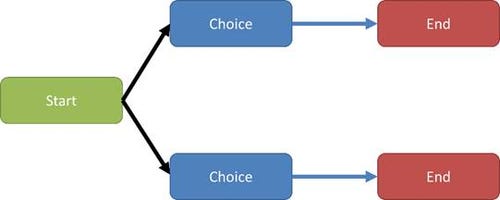

Figure 4 Simple Architecture

Games allow you to do more than that for the player. Games allow you to give the player much higher levels of autonomy or agency. For a sandbox game, like Minecraft, this is quite simple – the player has total freedom as there is no actual end game. There are still choices to be made, but they are unpredictable. How big will my house be, do I dig for gold, do I make a roller coaster. Rather than designing a choice architecture, you really just give the player the tools to support them.

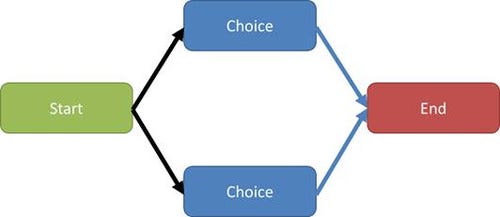

However, games with some form of narrative can be made much more interesting by allowing some level of agency beyond the simple “start at the start and end at the end” idea.

One option that you see is to give players “fake” options or choices. They get the choice to turn left or right at a junction, but really both paths will eventually lead to the same ending. They may experience different things taking the left rather than the right, but the end goal is the same, as we discussed in our Boy Meets Monster example earlier.

Figure 5 Simple Fake Choice

This sort of architecture works well in games that are only designed to be played once or where the gameplay is more important than the narrative. An example that comes to mind is that of older first person shooters. You could choose where to go on some maps or what your path was, but you always ended up in the same place. However, the choice had weight and meaning as it altered the tactics you would use each time you ran through the level.

Figure 6 Complex Fake Choice

There is nothing wrong with this sort of architecture if you can make the choices feel that they are meaningful and have significance to the game. You can also get very complex, with multiple twists and turns before you come to the inevitable conclusion.

A game that makes good use of this would be Tell Tale’s Walking Dead. Every choice you make alters the way the game will play. Who will live, who will die, how people react to you. However, the conclusion is always just about the same. You may have fewer people left and there may be some strained relationships, but the end of the game is the same each time.

The alternative to the fake choice architecture real choice architecture. Here the player's actions have real significance to how the game will play. A simple example would be the player back at the junction. They can go left or right. Either choice in this architecture gives a totally different outcome for the player. The choice they make has real meaning to the rest of the game.

Figure 7 Simple Real Choice

The significance can be less obvious than that of course. If you think about RPG games and how you can interact with non-playable characters (NPCs). Very often the choices you make in your dialog will determine how the NPC will react to you not just in that conversation, but later in the game. A simple choice to be aggressive could turn a whole faction against you, altering the whole balance of the game. Suddenly seemingly simple interaction become deeply meaningful to the game.

Figure 8 Complex Real Choice

The PS3 game, Heavy Rain, was a great example of this more complex choice architecture. There were many endings that could only be seen if you made specific sets of choices along the way.

In gamification, it seems as though the choice architecture is pretty straightforward. You need users to perform certain tasks, for which there will be some sort of reward. However, it doesn’t need to be that simple. You can design the user journey so that they can make choices along the way. The outcome is likely going to need to be the same for each user, but if it is a gamified system, the likelihood is they will only experience it once anyway! Add things in that are just for fun, but like a video game side mission, are totally optional.

Create simple narratives and stories that are affected by certain decisions, but make them have some effect on the outcome. I remember taking a “gamified” course. At the start, you chose your team and along the way you had the option to collect certain items. It seemed great, until the end – at which point it turned out that none of the choices you made had any influence on the outcome at all. All it had to do was unlock a simple message or change the last image, but no – nothing. I have no idea what the course was teaching, all I remember is the outrage I felt at being tricked into doing more than was absolutely essential because it felt like my choices may have some importance!

“Choices do not need to lead to alternative endings, just alternative experiences.”

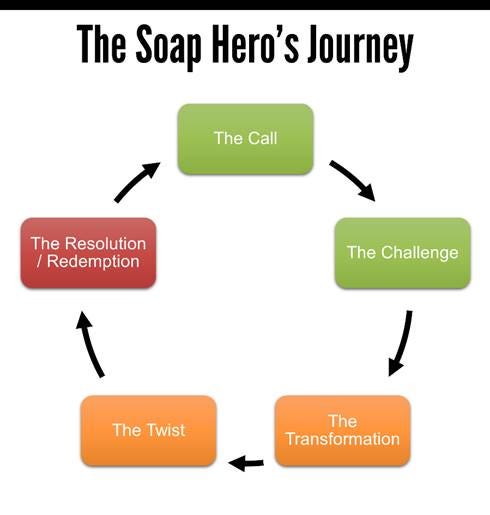

Now that we have an idea of how to construct the individual moments of the narrative, we need to have some idea of how it will all come together in a real story. I mentioned the simple narrative model I often use, the soap hero’s journey. I use this because it is easy to remember and is also the core of most short storytelling arcs – such as soap operas.

Figure 9 The Soap Hero’s Journey

The Call

The event that triggers the characters to start the journey

Plot

The Challenge

Conflicts, difficulties, tasks that the characters must overcome.

The Transformation

The change that happens to the characters as they learn to overcome the obstacles

The Twist (optional)

Often before the full resolution, there is a twist that forces the hero to practice their new skills or re-evaluate something they have learned during the transformation.

The Resolution

How all of the characters finally overcome or rationalise the challenges.

Uses all of their new knowledge.

This is nice and simple and works well with the concept of narrative atoms, keeping each atom of the story simple in its own right. This is how soaps like EastEnders do it, keeping each episode a short, self-contained story, whilst still having character progression and plot progression that can feed into the next episode. That way, those who have not seen the soap before can pick it up easily, whilst those that have been watching for years can enjoy at a deeper level.

Below is a silly example of an EastEnders plot put into the Soap Hero’s Journey.

The Call

Cat Moon has run away, but Alfie doesn’t know why.

He has to find her.

The Challenge

First, he has to find out where she has gone.

Then He has to find her

He has to find out why she left

Finally, he must bring her home

The Transformation

He finds out from her friend that she ran away to Spain because he was too controlling

Realizes he has to change how he feels about her past and grow up about it

The Twist

Gets to Spain and discovers it was all a lie, she was still in Walford!

The Resolution / Redemption

Finds Cat

Apologises to her and tells her he loves her

Convinces her he has changed

Brings her home and discovers she is pregnant

Duff Duffs...

As you can see from the ending there, this narrative atom can neatly bond onto the next episode!

Combining the concepts of Narrative Atoms and a simple story structure like the Soap Hero’s Journey, you can build strong narratives that can bend and twist to your heart's content. Just keep on top of character and plot development between atoms, and you will be fine!

Luomala, K. & Campbell, J. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. J. Am. Folk. 63, 121 (1950).

Comberg, D. Kurt Vonnegut on the Shapes of Stories. YouTube (2010). at <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oP3c1h8v2ZQ>;

The End

If you enjoyed this chapter, find out more about the full original book at

http://www.gamified.uk/even-ninja-monkeys-like-to-play/

Andrzej Marczewski

Gamified UK

@daverage

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like