Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Legendary Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell is still in the biz, chairing the board of casual in-game ad firm NeoEdge and working on restaurant gaming startup uWink - and Gamasutra quizzes him in-depth on his projects and video games today.

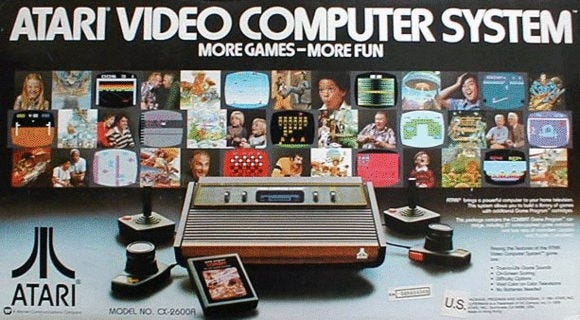

Though he's still most famous for (more or less) creating the arcade and console industries with Atari, a company he co-founded in 1972 before creating Pong and the Atari 2600, Nolan Bushnell still has new ideas to contribute to the gaming business more than thirty years later.

Though he left Atari all the way back in 1978, Bushnell went on to run Chuck E. Cheese's Pizza Time Theatre, as well as 1980s game company Sente. More recently, a new venture is delivering games in a whole new context with his chain of uWink gaming restaurants, which feature digital tabletop games in a fun, family-friendly environment.

As chairman of the board of casual-specific in-game advertising firm NeoEdge, Bushnell pays close attention to the casual games revolution - here discussing his views in how companies are missing the boat on audience targeting, as well as looking at how games might become the most successful medium for ad delivery.

Here, Bushnell and NeoEdge marketing VP Ty Levine answer Gamasutra's questions about the state of the casual games market and - of course - a few about Atari, past and present.

First of all, why target casual?

Nolan Bushnell: I've always been a contrarian. When people are talking about the size of the video game market, they're talking really about the habits and money based around 15 million people in the United States. That's basically five percent of the regular console game market.

If you look at the numbers, casual gamers right now are 40, and they actually probably should be closer to 100 million. And I'm trying to get back to the number of game players that existed basically in the '70s. In '79, 40 percent of the population of 250 million self-identified as a game player, meaning that they've played a video game within the last week.

When you look at that, you say, "What happened?" And I say that games got violent and lost the women, and got complex and lost the casual gamer. So now we're starting to see those coming back, and I actually believe that that market size will actually get bigger. The old story says that if you want to lead a mob, figure out where it's going and get out in front and say "Follow me!" (laughter)

So why go for the in-game advertising, versus say, starting a casual portal or something like that?

NB: I believe that the problem of growth for the casual game market is really about monetization structures. There are still a lot of people who will not put credit cards on the internet. There's even a larger number - i.e., kids and teenagers - that don't have credit cards. As a result, there's a real barrier to growth because of monetization issues. Advertising just gets rid of that.

NB: I believe that the problem of growth for the casual game market is really about monetization structures. There are still a lot of people who will not put credit cards on the internet. There's even a larger number - i.e., kids and teenagers - that don't have credit cards. As a result, there's a real barrier to growth because of monetization issues. Advertising just gets rid of that.

What do you think about that versus the "free-to-play, pay for items" model, like Nexon's Nexon Cash cards?

NB: It's still... any time you pay, you're going to have to have some kind of a credit card or some kind of a sponsor putting things up or scratch-off cards, like you have in China and Korea. All of those have an issue with them that is obviated by advertising.

What do you think are the biggest issues with cash cards? Because you can go into Target and buy those and that sort of thing?

NB: I think that those will work to some level. It's just that most people don't know about it right now.

A lot of companies are getting into the in-game advertising space. How does one differentiate?

NB: Primarily through technology. If you really want to do something exciting, you have to wrap games seamlessly, you have to give advertisers feedback, you have to easily convert. And not necessarily a priori - that is, think about advertising as you are building the game, but being able to go in and monetize your game after the fact with a really good game-serving engine. NeoEdge does that and provides all of the accounting data backup stream. It just does it the right way.

Ty Levine: It's a seamless experience. They've literally taken something that's already been created - the game itself. We're able to go in and take the game apart and put these ad insertion units in there without disrupting or modifying the experience that people are going to have while playing the game. That's really the key.

How would that be possible? From a design standpoint, how is it possible to do without interrupting the flow?

NB: Most games have some kind of a natural break point, particularly in the casual games space where there's "Round 1, Round 2." You know, that sort of thing. That gets pretty easy. Getting to a point in Halo is a little more difficult, except for when you get killed. (laughter) That sort of thing.

Or loading screens.

NB: But also, a lot of the other advertising in games... I call it the metaphorical equivalent of banner ads. With us, we have 30 second spots, which is the stock in trade. So an advertiser can click "network, cable, game," and it becomes part of an integrated and clever advertising strategy.

And then the other part about it, and why I'm really hot on this, is that if you look at actual remembering of the ad, we are so much better than either cable or network television, in terms of remembering the ads, and what have you. So over time, we should end up with a higher CPM than television. And television has done pretty well on their current CPMs.

TL: The brand recall is often in the 40 percentile, which you just don't see in any other medium. We just recently did a major CPG brand. It's a shampoo. I actually use it. I can't use the brand name, but that's beside the point. 66 percent of the people watch the entire ads that they saw. 87 percent watched at least half of the ad. You don't get that in any other medium, especially when you look at TV, and 93 percent of the people that own a DVR are skipping ads.

That leads me to ask one thing I was going to get to. How do you figure out how much people are willing to sit through or tolerate for ads in the games space?

NB: We really don't have a clue right now. We know that... what we're giving them, there's not a lot of pushback. In fact, I would say a lot of people are really happy to watch the ads as opposed to having to download [a game].

So we're clearly not there. We've not gone past one 30 second spot interstitially, and at the beginning and the end. If you go to the television model where you're stacking up ten 30 second spots in between, I don't think we could ever get there, nor do we need to.

What do you think of advergames, versus in-game advertising?

NB: I think both are very... well, I think advergames are very, very powerful. They're costly, they're nichey, but I think they're certainly strong. I think it's harder to weave in your message in an advergame as much as where you say, "Okay, now here's the message." Now, we can be consistent on that, instead of pushing it in. Sometimes, the advergames are a little bit constrained, or a little bit trite, I think. But I think as they become more important, they'll get better. I don't count them out at all. I think advergames make sense.

TL: Obviously, the up-front costs and the commitment is on a much different plane.

And also they have a tendency to be really, really bad, right now.

NB: (laughter) Exactly! I was going to say that, but... (laughter) You hit the nail on the head.

TL: Put it this way. I did PR 25 years ago, and we did Twinkies. David Letterman would've done it if he could jump into a vat of Twinkies filling. [Our client] said, "No way." You walk much finer lines with an advergame and what you can do with it, versus the ability to...you're now talking about the demographic with casual games, and fitting advertising with a much wider demographic than you are from the other side of the equation.

TL: Put it this way. I did PR 25 years ago, and we did Twinkies. David Letterman would've done it if he could jump into a vat of Twinkies filling. [Our client] said, "No way." You walk much finer lines with an advergame and what you can do with it, versus the ability to...you're now talking about the demographic with casual games, and fitting advertising with a much wider demographic than you are from the other side of the equation.

Pretty much every casual game company I've talked to has said that they know their market is bigger and wider, but they don't know exactly who they are. How do you target these? It would be great to say, "Okay, the 40 to 50-year-old women. We're going to sell this product."

NB: We actually do.

TL: You have to keep in mind... think of it as yes, we've got great technology, and we're combining with the gaming genre, but this is all taking place on the internet, so you have the benefits of what the internet provides from a marketing standpoint. So geo coding... somebody comes in and says, "I only want to reach people in the blank zip code region." The Bay Area, as an example. You're able to do that. You're also able to look at the behavioral components from where the people are coming from, whether it be portal or ISP, in not necessarily tracking technologies, but in targeting technologies that are out there today.

NB: We need to target by zip code, which gives us a hell of a lot of knowledge about household income, size of household, ethnicity... there's a lot of stuff statistically that we know.

TL: Keep in mind, remember that if you take a 30-minute television show, you've got eight minutes of commercials, but six of those minutes are national, which means that you might get an ad that that retailer or manufacturer doesn't even sell within three states. We never have to worry about that for our advertisers and from an advertising perspective.

Right. But you can't get age and gender without a credit card or something like that.

NB: No, but there are some ways. We don't get it now, but we will. At uWink we know exactly who's there, so we really understand how many people are playing what, because we see them with our own eyes.

TL: For example, if you go to Yahoo! and you play a casual game and it's got our ads in it, we're going to know all the demographic and psychographic information that Yahoo! has in their data analytics.

Same thing as if somebody came to... let's just take... Joe's Website, and Joe's Website is targeting 18-34 year old men, for example. Or Sue's Website, 25 to 54 year old women. We're going to know what door they're coming through to play that game.

So it's not as big of a stretch or a leap to say that we don't know the answer, because the answer is that we pretty much do know who they are, and we'll be testing different things such as... click what your demographic is before you even go to the download, and be able to serve up the right ad based on that demographic. So it's not as big of a leap as one might think, from a targeting standpoint.

Whenever anyone asks me to choose my age, I always choose the oldest one possible, so that would yield some interesting ad results.

TL: Might be! (laughter)

How is uWink going?

NB: Great... We're on a path to build the largest customer casual game network in the world. Last week, we served almost 150,000 games at one restaurant.

Are you going to tie this in with the advertising?

NB: Oh yeah. See, a lot of people say, "What are you doing in the restaurant business?" And I said, "It's all the same thing. If I can control the last 18 inches, I control the vertical." Pretty soon through franchisees and licensees I'll have 200 or 300 stores, each serving up 20 games per person, serving 10,000 people a week. All of a sudden, it's real numbers.

You're talking about world domination?

NB: Always.

TL: But you'll be surprised. Gaming obviously is not just an American phenomenon. At NeoEdge we just launched yesterday with one of the two largest social networking sites in Great Britain, PerfSpot, as their lone game channel on their site. Because they know it's a medium. And this goes back to what you were saying about how you figure out demographically. Well, PerfSpot knows who's coming through the door, thus we know who's coming through their door, and thus we match up the advertising that's appropriate.

uWink's third location, situated in downtown Mountain View, California

Makes sense.

NB: I actually think uWink is a social site. (laughter) With actual alcohol!

Remember, advertising across the board, if you target it well, is less offensive. I'd love to see Bud Light commercials, and I'm not big on Tide soap.

What do you think about the current state of the gaming industry? It's a very broad question, but...

NB: You know, I think everybody's making money, or at least most people are making money. I still think that there's a paucity of innovation, I think there's an awful lot of rehash and me-tooism. I think the most interesting games have yet to be designed. There are some massive, massive holes in the market that you could drive a truck through. I always like to quote my dad, who used to say, "Tomorrow will never be as crappy as it is today." (laughter)

What's your take on the crash of '84, and do you think there's any danger of it again?

NB: The '84 crash was predictable, and it was absolutely orchestrated by what I'd call massive incompetence on the part of Atari. It was really geared around trying to sell too much into a legacy product.

Remember, the 2600... we started marketing that thing in 1977, so in 1984, a significant amount of the money was still on that game which was based on technology that had been obsolete and should've been buried in '78 or '79. We made so many tradeoffs, yet Warner actually thought they were in the record player business, and that it was all about software.

So it was just... it wasn't homicide. It was absolute suicide. I can remember the day we shipped the first 2600, I told Manny Gerard, "Okay, that's obsolete. Now we've got to do something right." Because it was two years in development, we'd made assumptions about memory that weren't correct anymore, and we would've been ready, had Warner not had their head up their butt to come with the next level of machines, which was actually part of the Atari 800 series.

The Atari 400, with joysticks, is actually a pretty damn good game player, so it was meant to replace the 2600 with something that was stronger computers, better... it introduced sprites, and a lot of other things that just made it easier. So yeah, the whole thing was absolutely avoidable.

It seems like we're almost getting to the point where it could just be software, because the hardware is starting to...

NB: Plateau.

Plateau, yeah.

NB: Yeah, I've said that I believe that the hardware wars are probably over, or close to it, in terms of processor and MIPS. It's ridiculous to talk about how my photorealism is better than your photorealism. Who cares? I think there will be one more round of hardware, but I don't think it's going to do very well. I think it's going to be highly risky.

Do you foresee a future with one console, or one locus of gaming?

NB: Yeah. It's going to be the PC. Really, what the answer is, whether you talk about software solutions, like the Media Center PC or what have you, all you have to do is have a PC with a good graphics card hooked to the internet, hooked to the living room TV, with good user interfaces, and boom, you're there. That's starting to happen more and more.

There are huge benefits to open platforms, as opposed to closed platforms. The PC is open, so it's going to have another interesting part. A lot of people haven't woken up to the fact that you now have hardware encryption, and hardware encryption allows you to actually sell games that if you have a license for it you can play, and if you don't have a license for it, you can't play.

Most of the consoles have existed because of the inability to monetize software on the other consoles. Imagine actually having a game that you can sell in China and earn money from it. Because of the hardware encryption, the TPM chip that's now on virtually all motherboards, that's going to happen.

You don't think they'll find a way to get around that in China?

NB: Nope.

I'm skeptical of that. They always find a way.

NB: We always say that all of us are smarter than any of us, but when you have a private secret that is more than just a number -- that's an actual algorithm, in which the secret that's held in hardware -- you really can't get around it. Remember, games are a whole different ballgame than movies or music. If I can hear the music, I can copy it. If I can see the movie, I can copy it. Games, you're down into the bowels of code. You can maybe copy the concept, but you have to rewrite the game. And that is, in general, not a really doable thing.

But with hardware encryption, if your motherboard goes, so too do all of your games, unless there's something set up there.

NB: Well, key management is actually one of the areas that a lot of people are talking about, but in terms of monetizing your software investment, I think the thing has changed. I mean, software has always... you're always going to be able to crack it. Once it's cracked, it's cracked once and cracked for all, so there's an opportunity to it.

But when there's a different secret in every hardware system, crack once doesn't mean crack for all. I just think it's a really different thing. Remember, the reason you believe that China can crack any code is that up until now, it's been all of these software straw men who have said, "My system is crack-free." That's just not the case anymore.

It seems like maybe online registration keys are more feasible, in terms of being able to still have your game, if everything is connected online. If things are just stored locally, then developers or publishers...

TL: It also circles back to the whole idea of the whole advertising model of games. You're going to see more of that, and it lends itself to the PC and the combination thereof. You're going to see games that were being sold, six months from now, tests and trials of free-but-with-advertising-supported models with them.

NB: Yeah, there are a lot of games right now that were perfectly dreadful games last year and have zero market value, whereas if you play them for nothing or on an ad watch, all of a sudden there's some... the bad games are not quite so fail-hard.

In terms of having the PC be the future console for people, I think there's still a lot of consumer education that needs to happen for that to be possible.

NB: Absolutely.

My mom still asks me how to attach a document to an e-mail, because she can't figure it out.

NB: It's even worse than that. We've got one of these wire octopuses behind our television set, from the stereo system around it, the surround sound, three different kinds of video games, a DVD player, and this and that.

And I say to myself, "Okay, there are actually households in the world in which one of the members is not an electrical engineer. What the hell do they do?" (laughter) I spent a half an hour the other day just to get my DVD working again, because the kids have been messing around. I said, "There's got to be a better way, here."

TL: Hence the Geek Squad was born.

Once wireless stuff is the de facto standard, then it'll be changing. Who do you think is doing things right in the gaming industry, if anyone?

NB: I think that EA continues to do legacy products very, very well. I think that they have put a lot of money into Spore, which is sort of what appears to be the more innovative thing that's coming down the line from Will Wright. I think that Rock Band has represented a really good thing. Of course, Wii has expanded the game market massively.

I think in terms of the casual games space, I can't say that anything has been truly wonderful. I've been a fan of PopCap and Wild Tangent, but a lot of the other stuff is pretty pedestrian, in general. Nothing rises to the level of noticeability, from our standpoint.

What do you think of the missed opportunities, in terms of the casual games that people are failing to notice or failing to get across?

NB: I think that World of Warcraft has shown an interesting play dynamic. It started with Ultima and some of those, and I think that I don't see anything being worked on to replace that when it burns itself out, which it ultimately will. In fact, World of Warcraft just passed what I call the Bushnell Threshold.

The Bushnell Threshold is... I watch my sons, and because they're my sons, they tend to start things at the beginning, or sometimes a little bit before. So they play and play and play and play, and all of a sudden, they don't play anymore. They stayed with World of Warcraft for a long time. My older son all of a sudden got Mage 72 or whatever it is and quit. All at once. Cold turkey. I didn't think it was going to happen. And my 14-year-old is getting close to there, which is surprising.

I'm pretty sure that Blizzard's thinking about that.

NB: Yeah. Oh, absolutely. They have to be. But who's going to take their place? I don't see any intelligence out there that is looking to do anything other than another "level up your character by cutting and slashing," which I believe is the metric that's over.

How do you think that games will or should appeal to a wider demographic? Obviously in many games, there has to be some sort of conflict or competition or sense of achievement.

NB: "Sense of achievement" more than conflict. I think that we as men, based on our testosterone flowing, feel very comfortable with conflict, but a lot of women do not. They really don't want this to be a battle to the death, but they are really, really good at problem-solving and puzzles.

I think that the place that we're making massive in-roads is in female gamers, in some of the puzzle-based games. What is missing is story. There's pieces of story going on -- Cake Mania sort of has a story: the Horatio Alger of the baking industry -- and I think that some of these games are attempting to do story, but the stories are more tacked on, rather than built in.

Sandlot Games' Cake Mania

Think about the metric of the coffee table game. America grew up on Monopoly and Risk and The Game of Life and what have you, and in those, the game was about as much what happened with people sitting around the table -- what happened with each other -- as opposed to what was there on the table. We're finding that and we believe that in fact, we can create the board game of the future using technology, and capturing that sort of around-the-hearth...

TL: Scrabble's a great example right now. It's the biggest news story right now on the web, because it's become so popular from a social standpoint.

Like Scrabulous and all those things, right?

NB: And we're seeing... we've done Truth or Dare in the restaurant. All the way from bland questions to a little spicy ones later at night. Great fun! When you see it, you can almost peripherally... you walk through the restaurant, and the tables that are cracking up... they're playing Truth or Dare.

It's very fun to see what we've learned about people interacting with each other as peers, parents interacting with kids... we've got a group of little old ladies that come into the restaurant every Tuesday afternoon - or is it Thursday?

One of them has a Manhattan, the other one has white wine, and the other one has a glass of water. They have a salad, and they play games for two hours. One of them has to be in her late 80s or early 90s. Just... feisty, little old ladies having a good time. Those are our demographics.

I think it's interesting when people say that women avoid conflict in games. It makes me think that maybe it's just the wrong kind of conflict or competition, because if you get any of my female friends together, there's a lot of competition going on there, and also any girl that I've ever dated, you'd be hard-pressed to tell me that they do not enjoy conflict.

TL: The lowest number I've seen in the casual gaming space - at 18-plus demographic, 25-plus, 35-plus - is that 60 percent of the people playing are women. The highest number I've seen is upwards of 70 percent. It's got to tell you something. They want the interaction with what's going on on the screen, and they want the competition that's involved there. It's just that they're not playing with a gun or along those lines. That's really it.

NB: I think "competitive" is the right answer. What I find that women don't like is that they don't like war things, they don't like blood and guts, and they don't like monsters. All the cool stuff! (laughter)

I'm curious to know... Atari has been doing some weird things. Do you pay attention to them at all these days? Are they in your peripheral view?

NB: You know, no matter how misbehaved your children are, you still sort of look at them, even though they've left the house and have been in prison for a year. (laughter)

Covered in tattoos...

NB: Covered in tattoos, you know, in and out of rehab...

So what do you think of Atari's current state? Do you think they can turn it around? Do you sometimes wish it would just go away?

NB: Well, you know, I've always had a dream of architecting the reversal of fortune. The real problem that Atari has really had for the last 15 years is that it hasn't stood for anything. I think a name and a brand has to stand for something, otherwise it's not a brand. It's a logo. I think that the people who have been running it have never had a core vision.

I always had a core vision of what Atari was going to mean, and I believe that without that, you're just flopping around, and you will end up having a hit and then a miss, and you're not creating any value. So I strongly urge them to have some core values, hopefully, that are going to be important in the future.

Do you know about Phil Harrison joining Infogrames? What do you think about that?

NB: I don't know him well, so I can't really reply.

He's a really smart guy. I think if anyone could do it, he could probably do it.

NB: Well if he wants to give me a call, I'll give him a hand. (laughter)

He obviously did it because he likes a challenge.

NB: It's a big challenge.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like