Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

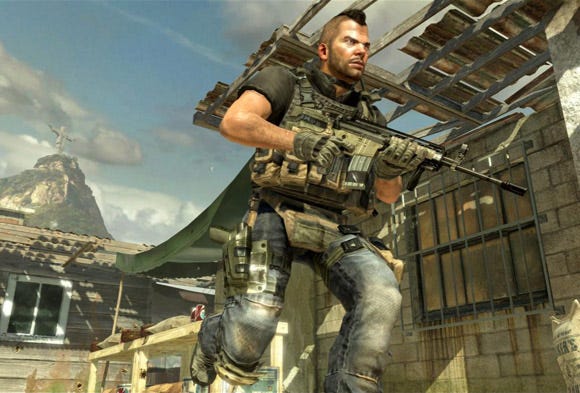

Gamasutra sits down with Joel Emslie, Call Of Duty: Modern Warfare 2's lead character artist, to discuss the processes by which the most respected name in war games gets its considerable visual punch.

One of the most important aspects of making a game realistic is its graphics -- a core conceit of the generational transitions the console industry is founded on.

And for a game like Infinity Ward and Activision's Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, that's even more strongly true; drawing inspiration from what's happening in the world now and bringing it credibly and viscerally to your screen, the Modern Warfare games live and die by visual veracity.

It's particularly worth noting that the Call of Duty games are driven as intensely by character action and interaction as they are by enemy combat -- two major, and complicated artistic problems to tackle.

To find out more about what goes into the visuals of what's already being billed as the biggest game of the year, Gamasutra sat down with Joel Emslie, the game's lead character artist.

Here, he discusses the processes by which the most respected name in war games gets its considerable visual punch:

The name of your game is Modern Warfare. By its nature, the game's characters have to compete with our intrinsic knowledge of the actual modern world we live in, and what we see on the news. How do you approach that as a character artist, along with the practical concerns of making gameplay-readable designs?

Joel Emslie: First and foremost, it's getting animation right. The human eye picks up on everything. It doesn't need very many pixels of movement to realize that something looks fake, so the movement is first and foremost.

We've improved all of our rigging. We've improved the way we make faces. We've really been tightening the screws with what we've been doing this whole time on the PC, Xbox 360, PS3 -- just really stepping it forward each time we make a new game and learning from all the mistakes from last time. But to set it in reality, the first thing is the animations, getting it to move right.

The second thing is that we're always inspired in trying to be as authentic as possible, but to get things to read properly in a combat environment with the fog of war, particles, tracers, and whatever else.

You need to step into a thought process that's almost more from a theatre standpoint. So you're looking at costume design. You're getting parts of your characters to read properly, or to make things look more realistic.

We have texture streaming; that really helps. The variation that we have in this game is a step beyond what I've ever worked with in my career. So we have that fidelity, but fidelity is nothing if you're not using it properly -- the way we lay out our characters, the way we're packing pixels into their arms and legs and packs. We're really pushing how we do ambient occlusion, so the packs and the gear sit on the character properly. They settle in to look more realistic.

You have to feel it's natural. Even getting characters like "Soap" MacTavish to stand out. I've been looking at certain movies for a long time. I'm a huge fan of [2003 war movie] Tears of the Sun. There's a character that caught my eye.

I've always wanted to do a character inspired by that, with a mohawk, which just pops. You can just spot him a mile away. He's a great character. He's in there telling you what to do, and you can spot him, which is great.

We're trying to bring that element into other characters as well, refining their headgear so they stand out, and trying to get them to pop.

On the notion of that theatricality, people frequently discuss games like this and say, "Why does it all have to be photorealistic?" But the reality is, there's still a lot of artistic interpretation that has to go into it, for it to read the right way. How do you strike the balance between being too clinically realistic, and not realistic enough to be convincing?

JE: It's an old design philosophy that everybody learns. It's Design 101: Function precedes form. Everything moves properly. You need to design a costume that actually works with the animation and movement with the character.

Some stuff can be too hyper-real. If we were approaching a super hyper-real [aesthetic], there would be a lot of really crazy stuff we'd have to do in order for things to work that just aren't there yet. You have to accommodate for that.

One other thing we did is to sit down and take a look at what worked on the last project and what could work again for this one. The first thing we found is that everybody's always making grenades. They're making grenades over and over again. Every time I assign a squad to somebody, he's got to go make grenades and smoke rounds and everything.

You mean artists? They're remaking all those assets from scratch?

JE: Yeah. If I've got a squad [to design], I'll say, " I'm going to do this squad. I'm going to have to make a new grenade. Do you already have the grenade? I might use it, I might not."

Why is that, out of curiosity?

JE: Artists, when they step into something, want to tackle it and make it work for what they're doing. So we started to standardize that type of thing. When you look at the modern theatre right now, when you globetrot around the planet, the loadouts and the gear and the equipment start to get very similar.

They're manufactured by certain companies, and [the differences] really come down to palette and some minor details here and there. For the most part, modern gear has similarities that you can standardize and work off as a base.

So we stepped into that and we put a lot of design into it. We designed loadouts -- an assault loadout, a [light machine gun loadout], and so on. You really can look at a shotgun guy, and see that he's very noticeably wearing a bunch of shells on him. There might be a "bad guy" version of that and a "good guy" version. We can step into palettes there, which really helps.

And all that gear in the design is inspired by and is based on, as closely as possible, realistic gear. We're not making buckles up from scratch. We research all this stuff like crazy. A couple of us have even gone shooting on ranges.

We'll go out and shoot weapons and get familiar with all the gear as much as possible. You start to get into some really cool stuff -- high-speed rigs, snaps, equipment that ensures you don't drown if you fall in the water.

It just helps us make cooler loadouts. We incorporated all that into our basic loadouts. We all sat together, assigned the loadouts one by one to each person, and then shared them amongst ourselves.

Each time we got a new squad, the character artist could focus on what really matters -- the headgear, the bust. What you're shooting at most of the time is this right here, so they focus on that. They've got a great base to build on, and then you're just making it your own from there on out.

Has that pipeline kind of changed much from Modern Warfare? It sounds like you've had some revisions to the process since the last game.

JE: Yeah. We had a lot of ground to cover in this game, a really high demand for multiple squads. We're going all over the globe with this game. And there's a lot of hero play. We have a lot of main characters that need to stand out properly, so a lot of things had to change.

The biggest change was how we did our faces. We got Steven Giesler, who worked on [the computer animated film] Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within. He's one of the only artists I know who has his art on the cover of Maxim magazine. He's a great guy.

He's a genius when it comes to the human face. He's just brilliant at it. He came in and really restructured the way that we're doing our faces. It comes to that same philosophy of the loadouts, where we refine something that we've been doing over and over again to create a really, really solid foundation.

He built this system where, for normal characters or just for variation, we could go in and blend different characters together. We could take a Caucasian, a South African male, and a female face, and blend all those in together and get this really great-looking unique face.

Just with a slider and a dial, he'd throw it into his computer and go, "That one's great. Let's use that one." He'd then bring it over to the artists, and they would work on it, put on some scars, mess it up, put some flare into it, and then send it into the character pipeline.

It's badass. That was the biggest change that we did. The other stuff is more along the lines of what I'm saying -- refining how we're doing everything. The tools to make these things have come a long way in the last five years. That really helps.

I imagine it's fun to be working in this structure Infinity Ward likes, where you go from protagonist to protagonist over the course of the game. There must be a certain pressure to try and keep one from being too much more memorable than another.

JE: Truth be told, when the players get their hands on it and see the characters, we'll see if we've been really successful with the characters being really noticeable and memorable, along with their voices. When you combine all that together, you've got a character that stands out.

But there will be other characters who are very military, and it's hard to act through, or to get across with all this headgear, that it's a special character. The voice helps. But it's a challenge. It's a big challenge. Like I said, we have a lot of fidelity. I'm really unbelievably proud of the character team. The whole team in general, artistically, really brought it a step forward with all that stuff, along with environment and everything else. It's all crazy this time.

What's your environment process like? Do you pair up a level designer with an environmental artist?

JE: No. It's more like fighting fires. When we go in, we have level designers who are really good at geometry, and they can rip things apart and put them back together really quickly. Then we have level designers who are unbelievably gifted at scripting. And we have some who are good at both. Those are the higher, upper-echelon guys who can really just go in and kick ass at things.

Then they're all always supported by an environmental art team that comes in and does positional lighting, and all of that stuff. Sometimes, certain level designers can do that all themselves, and they're talented. But we tend to go in and triage things as we go. The design is always rapidly changing.

Things are changing constantly up until the very end. If we're not satisfied with what's going on here, we'll come in and firefight it.

Finally, I know there's been some chatter about this online - but has Bobby Kotick really succeeded in taking all the fun out of your video game development process?

JE: No way. Absolutely not. Kotick's a great guy.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like