Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

"Getting Over It" is the kind of game I would never make, it's super painful and not my thing at all, and I love it.

If I had to select a single game designer that embodied the exact opposite of my personal design aesthetic, it'd be Bennett Foddy. Whereas modern games have mostly filed off all the rough edges of the early NES-era, each Bennett Foddy game is a shrine to one of those rough edges, carefully chosen, plucked off, and sharpened to a gleaming point.

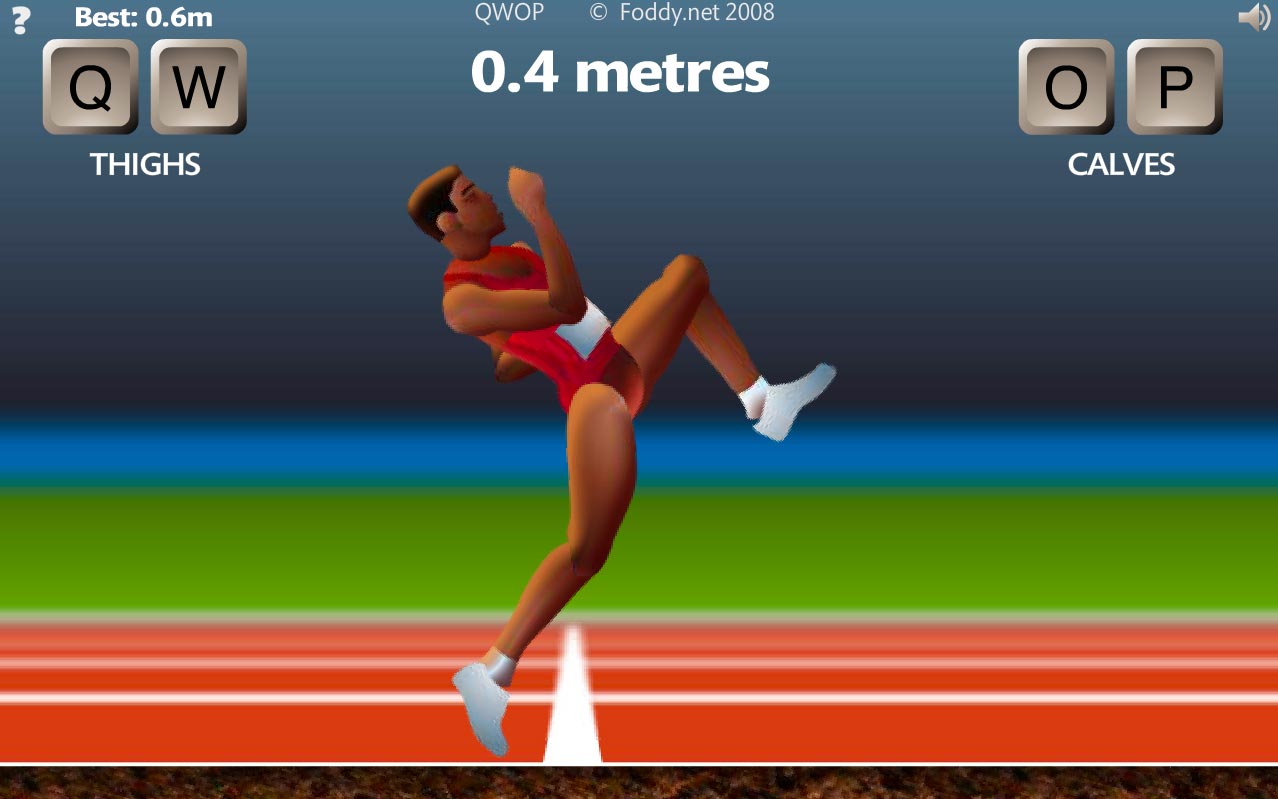

"QWOP is a simple game about running extremely fast down a 100 meter track."

Foddy's games are weird and intentionally infuriating, and despite being so totally not my jam I can't stop playing (and thinking about) them. I've been meaning to write an article like this for a while, and today the perfect opportunity arrived.

His latest title, Getting Over it, has just been released:

This game is a doozy, even by Bennett Foddy standards.

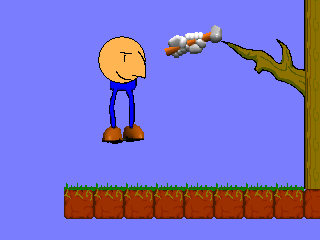

First and foremost, it's an homage to an obscure "B-game" called Sexy Hiking, developed by an enigmatic Czech developer called "Jazzuo"

"The hiking action is very similar to way you would do it in real life, remember that and you will do well"

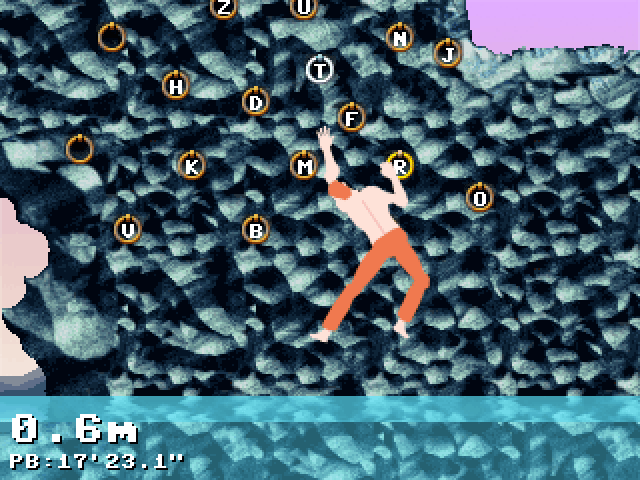

Sexy Hiking and Getting Over It share the same basic mechanic -- you've got a weird little dude who's trying to climb over obstacles using nothing but a sledgehammer that follows your mouse cursor, colliding with objects with pixel-perfect precision. That's it. That's the whole game.

The only "progress" is how far you've physically climbed, and the threat of plummeting all the way back to the bottom is always just one slight mouse wiggle away.

Unlike Sexy Hiking, Getting Over It features professionally done (and legally procured) graphics and sound, as well as non-glitchy code, but it's also a weird and compelling sort of video game essay, as a narrator (presumably Bennett himself?) explains his design ideas and reflections on Sexy Hiking whenever you reach a new point. And when you unceremoniously knock yourself down for the 500th time, he reads a new inspirational quote about triumph in the face of adversity.

This is exactly the sort of game I'm naturally inclined to hate, but I don't. I love it.

Why? Maybe because of how honestly and directly the game presents it's own design aesthetic.

I use "design aesthetic" here rather than "design philosphy" because the latter carries the flavor of a big world-view with lots of truth claims, and today I'm talking about subjective preferences. I prefer to play (and make) certain kinds of games, for certain kinds of people. Clearly, Bennett does as well:

"I created this game for a certain kind of person. To hurt them."

On the "hurt them" part I'm the exact opposite, and my personal aesthetic takes a rather hard line on this. In 2004, I read this article by Ron Gilbert and adopted the parting line as my personal motto:

"The average American spends most of the day failing at the office, the last thing he wants to do is come home and fail while trying to relax and be entertained."

My game Defender's Quest set out to explicitly eliminate the time sinks and pain points of the traditional RPG structure, going to arguably extreme lengths. The game has customizable reward multipliers, can be blazed through in three hours under the right settings (even though it has 100+ hours of content), doesn't hold the story hostage behind arbitrary challenge, and features zero points of no return, not even after you start a New Game+.

But whether we're inflicting pain or stomping it out, I like to think what Bennett and I have in common is respect for pain.

I don't begrudge anyone their hard-ass games, whether it's Cuphead, Spelunky or Dark Souls even as I continue to advocate for adding more options to let players experience games the way they want -- particularly rudimentary mod support.

That said, a lot of conversations about "pain" and "difficulty" in game design focus exclusively on the consciously designed challenges, whereas most games are filled with unintended frustrations, often the sort the designer wasn't even aware they'd put in. I covered some of this in Oil it or Spoil it!, but this problem exists at a higher level, too -- for instance, giving the player an interesting choice that only leads to Loss Aversion, or a bunch of cool sidequests that accidentally invoke the Checklist Effect.

And this is what's so fascinating about Bennet Foddy's games, particularly Getting Over It. Everything about this game is consciously chosen. Every setback, every frustration, every curse leveled at the sky is absolutely intentional, and the narrator's soothing voice is there to acknowledge it, and it's strangely motivating.

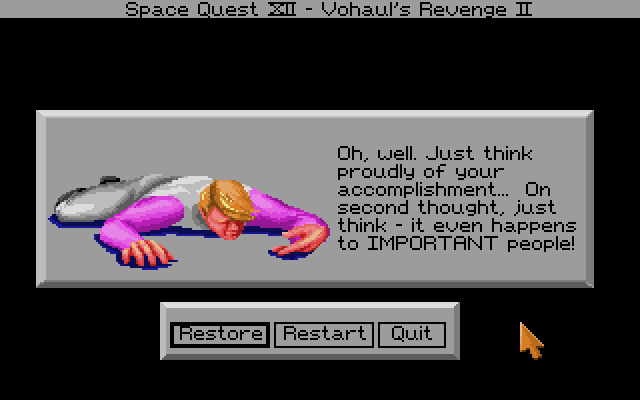

I'm sure some will read a mocking tone into the narrator's encouragements (punctuated by occasional public domain blues tracks), but I was struck by how sincere everything comes across. After all, the traditional approach to mark a video game player's passing is to make to fun of them :)

There's more to be said about the design process, but honestly, play the game (or watch the parts you can't reach on youtube after you've given up) and Bennett will tell you all those details himself. The game doubles as its own director's commentary. So to round this out, I'll move on to things the narrator doesn't touch on.

The controls, as limited as they are, are really smooth in a strange sort of way. Your sledgehammer goes only where you tell it to, and your frustrations come from it not being able to reach where you want rather than going someplace you didn't direct it. Oh, you'll be plenty mad at it going somewhere you didn't want -- but you always put it there, somehow. I constantly find myself wanting the hammer head to clip through the terrain just this once and solidify only after I click the mouse cursor. But no, if you want to reach up and hook that ledge, you have to get it there yourself, without carelessly smashing against the wall and propelling yourself downwards.

I suspect that a lot of reviews of Getting Over It will invoke the word "Masochistic" or "Sadistic." I'm not quite sure that fits. The game is full of torments, but I don't feel like the game (or it's designer) enjoys tormenting me, exactly. It's more like, "I built you an obstacle -- unflinching, uncompromising, patently impossible. You won't believe you can surmount it, but it's possible. It's also really, really, hard."

This is in sharp contrast to Platform Hell games filled with Kaizo Traps, where the fun (for both designer and player) comes from being intentionally killed by traps you could have never anticipated:

To be fair, Bennett isn't above this sort of behavior in his other games:

Getting Over It is exactly the sort of game I would never make. Most people who try to play it will get super frustrated and quit immediately. It has no difficulty options, no checkpoints (that I've found), and aggressively autosaves to prevent save-scumming.

And yet, there's an experience I can't really get anywhere else except by flinging my face against this mountain over and over again: how after hours of fruitless climbing, I suddenly surmount the whole cliff in a few seconds of mad, whirling sledgehammer somersaults, not believing my own eyes as muscle memory kicks in and I pull off the impossible with minute precision. And then a single mis-placed stroke sends me careening back to earth.

I still haven't finished the game, of course. I probably never will. But I'm glad I tried, and I'm sure Bennett feels the same way.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like