Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In his latest feature, designer and author Ian Bogost analyzes Jason Rohrer's fascinating new art-game Between to help map out a new, indirect style of multiplayer gaming.

[In his latest feature, designer and author Bogost analyzes Jason Rohrer's fascinating new art-game Between to help define a new, indirect style of multiplayer gaming.]

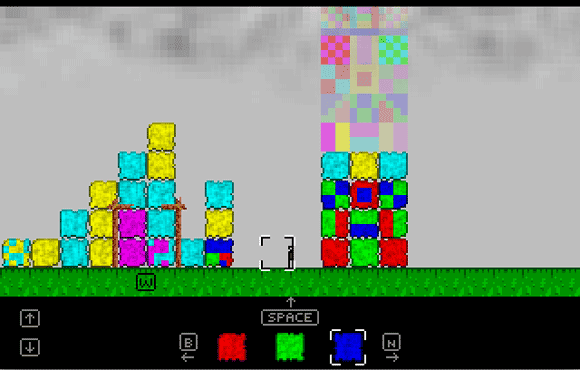

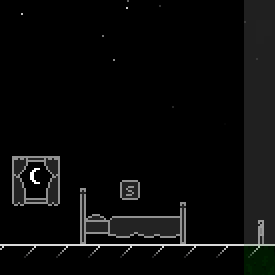

Players of Jason Rohrer's previous art games Passage and Gravitation might squint at first when trying his latest title, Between - intriguingly made for Esquire Magazine as part of its 'Esquire's Best and Brightest 2008' issue.

Sure, they will recognize Rohrer's characteristic style: a preference for pixellation and visual austerity, the simple control over an abstract character, and an environment both naturalistic and man-made.

But unlike many of his earlier games, Between does not directly model a human emotion or experience in the way Passage did with mortality or Gravitation with inspiration. At least, not on first blush.

Between is a two-player game, in the way that Pong is: it cannot be played by a single player. Once connected to a counterpart over the network, players still do not see each other's progress, at least not right away.

Players are given little explicit direction beyond what objects on the screen imply: a tower of spaces for colored blocks stands at right, a wooden frame for placing blocks at center.

The player can place and move blocks of a few different kinds and then "wake" or "sleep" to move between three similar versions of the game world. Four blocks placed in the wooden frame at center construct a new block that combines their components when the player wakes, and this process of constructing new blocks quickly becomes necessary to build up the tower.

The thing is, the player can only place primary colored blocks to start (red, green blue), but many of the blocks on the tower require secondary colors (cyan, magenta, yellow) as components.

After a while, combinations of secondary color blocks appear based on what the other player has been doing with their blocks and tower, meaning that the player has limited control over a resource that he also needs to progress in the game.

The game gets hard very quickly. Part of the difficulty is a spatial relations challenge: as the tower gets bigger, the blocks require more complex components, which in turn have to be created through multiple sleep/wake cycles across the three renditions of the world.

But the real trial comes from the player's lack of control over available resources: the cyan, magenta, and yellow blocks needed to make parts of the tower have to be coerced out of the other player somehow.

Means for doing this is deliberately left out of the game: one option is for players to talk to each other and try to tease out the logic by which magic blocks appear. Another is for players to exercise patience and simply wait for the right blocks, an event that may never come to pass.

Still another is to try to manipulate the second player's blocks indirectly by attempting to create blocks on the other player's screen which, when used, might result in needed resources on one's own.

Two people playing on laptops in the same room enjoy an additional clue: as the tower builds up correctly, music begins to play with increasing detail and volume, which provides a hint about a counterpart's progress (in a brief statement accompanying the game, Rohrer discourages players from looking at each other's screens).

An ongoing debate rages about which is "better": single-player or multi-player games. Well-known MMOG designer Raph Koster has argued that single-player games are an "historical aberration" wrought by unconnected computers. People, the argument goes, have played games together since the dawn of history as a way of testing roles and enacting traditions.

Theorists of play like Johan Huizinga and Brian Sutton-Smith have made similar observations, studying the ways play is central to human culture rather than set apart from it.

Scholars, players, and the general public alike have observed how popular multiplayer experiences, from World of Warcraft to Facebook, both improve and change the way we relate to other people. Indeed, one of the tired aphorisms of today's technology business culture is the promise to help people "connect with your friends."

Most video games take one of a few tacks regarding play with others. Some games, like Super Mario Bros., are solitary, with multi-player experience limited to spectatorship (BioShock) or hot-seat-style sequential play (Asteroids).

Others focus on competition, whether through strategy (Diplomacy) or combat (Super Smash Bros.), synchrony (CounterStrike) or asynchrony (Scrabulous).

Still others focus on collaboration (Rock Band) or co-creation (Little Big Planet). Recent trends in social networking and massively multiplayer games might suggest a fourth kind of experience, that of socialization. And many games include variants or modes that cover solitary, competitive, and collaborative play.

But there are many more ways of understanding how people relate to each other than just through solitude, competition, collaboration, or socialization. Between is such a game.

The concept of the "other" has a long and complex history in philosophy. Building on the thinking of Freud and Hegel, French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan advanced the idea of the other as a key organizing principle of the self. French philosopher Immanuel Levinas argued that the Other remains forever unknowable.

For Levinas, the Other serves as a fundamental grounding for ethics. These thinkers understand Others in a radical way: the other is not just "someone else," but something infinitely different, so much so that the chasm between self and other can never be traversed, mended, or united.

From this frustration comes the concept's power. Unlike collaboration or competition or indeed solitude, the concept of the Other reminds us that individual existence is comprised partly from disconnectedness.

It is here that Rohrer's game takes root. Its title, Between, already suggests that the game deals with the space separating the two players more than the common goal that appears to unite them (constructing a tower of blocks).

When the game begins, the player has the initial impression that the second player is unimportant; no trace of the other character appears on screen. As one completes the lower-level blocks, this sensation continues, until the reality of the blocks with secondary colors presents itself.

Here, temporarily, the player feels as though a collaboration with the second player will be both fruitful and facile: all that is needed are enough secondary color blocks to allow the solitary construction of the tower.

But then, and quickly, disappointment sets in: one player cannot simply request specific blocks from the other; rather, a complex and unseen process generates shadow blocks based on the structure the other player builds. This structure too remains unseen.

The resulting experience is where Rohrer's characteristically sophisticated treatment of human experience through seemingly simple game dynamics takes root. Both players will likely wonder, perhaps aloud, what kind of game would make progress so inscrutable.

The two may even try to strategize, carefully sharing moves in an attempt to trace the edges of the computational process used to generate counterpart blocks on the other player's screen.

But this process too has its limits: eventually compound blocks must be created across multiple screens in the game, increasing the cognitive load of both players to the breaking point.

Between does not try to create identification through collaboration. The game aims to create a relationship between two players that focuses both on the chasm that separates them as human beings, rather than on a common foe, or one another as foes, or as a medium for social interaction.

When we talk about games, we normally use the language of conjunction, whether through accompaniment ("to play with") or conflict ("to play against"). Whether for competition, collaboration, or socialization, multiplayer games aim to connect people in the act of play itself.

Between takes on a very different charge: it aims to remind players of the abyss that forever separates them from another. In the face of this gulch, the best we can do is to attempt to trace the edges of our cohort's gestures and signals, as players of Between do when they interpret the origins of the weird, mottled colored patterns that appear as if from nowhere on their screens.

If most multiplayer games are conjunctive, Between is disjunctive. It is a game that aims to disturb notions of cohesion rather than to create them. And if any common sympathy arises from the experience, it is a feeling of comfort in the commonality of one's inevitable isolation.

Herein lies the weird logic of Otherness: apart from death, it is the one thing we human beings all share. And in so doing, it joins us even as it pushes us apart.

Before you conclude that the disjunctive multiplayer experience of Between is limited to the domain of weird independent art games, consider another, very different title that also employs disjunctive multiplay: Spore.

When Will Wright first began talking publicly about his "SimEverything" title, one of the ways he described it was as a "massively single player game." The game's many editors would allow players to create their own creatures, vehicles, buildings, and even planets.

To construct a rich, credible universe, these objects would be uploaded silently to a server, where they would then be deployed into other players' games.

Unlike purely generative stuffs, some semblance of coherence would be insured, since human hands would have created each object to be shared. But unlike so many popular user generated content websites, Spore's various matter would not promote individual creativity as its first goal.

Rather, it would serve as the Other in Spore's vast galaxy. The creatures, vehicles, and buildings that the game draws from a common pool become the beings, conveyances, and shelters of alien species.

As in Between, Spore's players do not work together, nor against one another. Instead, each player's creations, so familiar and transparent to the individual player, become the aliens in other player's games.

As in Between, Spore's players do not work together, nor against one another. Instead, each player's creations, so familiar and transparent to the individual player, become the aliens in other player's games.

"Alien," a word that literally means "other," evokes anxiety because it suggests something utterly unfamiliar, making the alien creatures of Spore an effective source of disjunctive play.

In today's world, everywhere we turn we are enjoined toward commonality. Facebook wants us to see the same groups our friends join, the same ads others like us click.

Amazon.com and Netflix help us understand what others who liked what we like also bought or borrowed, and YouTube and Flickr help us see what graced the retinas of others who watched or looked at what we just encountered.

In the face of such obsession with commonality, disjunctive multiplayer experiences remind us that no matter how similar cultures, marketplaces, or communities might make us, some aspects of other people remain ever out of reach.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like