Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What lessons can we learn from Zynga's popular game Words With Friends? In the latest Persuasive Games, video game researcher and designer Ian Bogost examines whether social games can find room to grow.

What lessons can we learn from Zynga's popular game, Words With Friends? In the latest Persuasive Games, video game researcher and designer Ian Bogost examines whether social games can find room to grow.

Imagine that you were a big game studio that had built your business around free-to-play social network games. Say that you had recently gone public, but your stock was down sixfold from its IPO price. And let's also imagine that the social network facilitating most of your business was also taking a hammering on Wall Street. Imagine too that analysts had suggested that an underdeveloped and under-executed mobile strategy was cause for worry among investors in both cases.

Oh, and just for kicks, also imagine that you'd recently spent a couple hundred million dollars to acquire a smaller studio with a red-hot mobile title, but that said game's performance had declined rapidly in the quarter after the acquisition. In the meantime, imagine you had let your most successful mobile title wallow in disregard since acquiring its creator more than a year before.

Obviously, this isn't a hypothetical scenario. It's the recent story of Zynga. With its stock down and its prospects in question, the company has faced multiple executive resignations and fielded tough criticism from financial analysts.

Even if the shift from web to mobile social games is still just a theory, Zynga seems to have all but disavowed a proven, continuously successful game that performs well across both platforms: Words With Friends.

Some history is in order. Words With Friends was the second title from Dallas studio Newtoy, which first released Chess With Friends on iPhone in 2008. That's the same year an infringement lawsuit from Scrabble's North American copyright owner Hasbro had driven Scrabulous off of Facebook after a year of intense popularity on the platform.

Newtoy thus had a number of things going for it in advance of the release of Words With Friends: a technology infrastructure for facilitating asynchronous play for mobile devices; a brand-name for such games ("With Friends"); the untimely demise of an incumbent competitor (Scrabulous later relaunched as Lexulous and Hasbro dropped its lawsuit, but the game never achieved its former glory); and a helpful reminder of the legal obstacles that the studio might face if it didn't offer a substantially different audiovisual presentation from the genre's ur-game.

Still, Words With Friends was hardly a sure thing. Electronic Arts had managed to get an officially licensed iPhone version of Scrabble to market in 2008, and with the downfall of Scrabulous it seemed impossible that an upstart like Newtoy could upset a game with a 60-year head start.

But amazingly, it did. We'll never know exactly why, but for once design may have triumphed over marketing. Not game design, either, but visual and experience design.

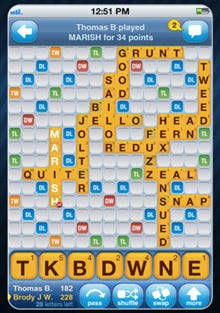

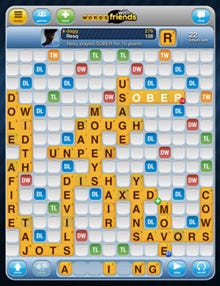

Visually, Newtoy's crossword game wasn't very different from Scrabble or Scrabulous in play, although the developers wisely revised the appearance of the tiles and board along with the position of bonuses and the value of individual letters.

Visually, Newtoy's crossword game wasn't very different from Scrabble or Scrabulous in play, although the developers wisely revised the appearance of the tiles and board along with the position of bonuses and the value of individual letters.

These alterations partly helped the game avoid copyright infringement challenges, but they also recast the familiar crossword formula in a new visual light. Next to EA's faithful recreation of Scrabble's staid wooden tiles and pastel board, Words With Friends' bright, rounded, plasticy look felt fresh, clean, and well aligned with the minimalist mobile devices on which the game was first played.

From an experience design perspective, Newtoy did an expert job with the app's startup and "onboarding" experience. Back in 2009, EA's iPhone Scrabble displayed a lengthy animated splash screen (it still does), then required registration to start games with friends.

Newtoy not only made its app load quickly, but also allowed users to start a game just by entering another player's username. The friction was low, so playership increased. Over time, Words With Friends has added many more layers of UI and registration, but did so after gaining enough users and mindshare that the network effect helped overcome a bulkier experience.

Given Zynga's ongoing interest in buying studios for their users as much as or more than their game properties, it's clear that these two decisions were central to making Newtoy an appealing acquisition target for the social game Godzilla.

Since becoming Zynga With Friends, the studio has released three new "With Friends" games: Hanging With Friends, Scramble With Friends, and Matching With Friends. The first two follow the same course as Words and Chess, adapting popular folk- and board games (hangman and Boggle, respectively) for asynchronous mobile play.

But none of the studio's subsequent titles match the popularity and influence of Words With Friends over time. It boasts 13.4 million monthly active users (MAUs) on Facebook and has held the #1 top paid app spot on iOS as recently as last week (it's down to #72 this week). Of the other titles, Scramble With Friends has performed best, with 4 million MAUs on Facebook, and an iOS ranking of #25 this week. By comparison, Draw Something is down to 11.2 million MAUs on Facebook and is the #251 paid iOS app.

It’s tempting to ask why Zynga With Friends hasn’t managed to produce a "With Friends" like Words, but that answer is somewhat obvious: hits are rare and hard to predict, and previous performance doesn’t guarantee future success. A more interesting question is this one: what lessons can we learn in advance from Words With Friends about the future of game development?

Newtoy's games haven't really been game designed games. The developer started with Chess With Friends, adding appeal to a classic by offering an effective matchmaking mechanism for asynchronous games in the early days of the iPhone. Chess is popular but not as accessible as crossword games, and Words With Friends offered both increased reach and a refinement of asynchronous play on mobile devices and eventually on the web as well. Newtoy changed some of the details from Scrabble, but nothing substantial enough to qualify as design innovation.

Zynga has received a lot of flack for antipathy toward game design, favoring the "borrowing" of existing designs, to put it kindly. Indeed, the company's overall corporate strategy has been one of trying to outrace itself, launching new games or acquiring new game studios and shifting players to new games as old ones atrophy.

Still, Zynga allows its studios to operate relatively independently, and the design of Words With Friends predates Newtoy's Zyngaficiation. It's possible that Newtoy just prefers a more conservative approach to design, one focused on the re-packaging of classic designs rather than the invention of new genres.

Design innovation purists might scoff, but such a reaction is unfair: after all, there are lots of ways to do game design. And admittedly, Matching With Friends, released only a few months ago, does offer some design novelty, even if it does so within the proven match-three genre.

But Matching hasn't taken off nearly as much as Newtoy's other games anyway. Given the evidence, why not stick with what works -- presenting familiar designs in fresh packaging?

The changing marketplace might offer one reason. It's still too early to tell if the social game trend was just a bomb with a fuse long enough to help a few companies sell or go public, and sustainable enough only for their senior-most management to cash out big. But no matter the answer, things seem to be changing.

Perhaps one of those changes will be a return to deeper game design. Not just deeper in systems design -- finding truly novel designs even in a familiar design space -- but deeper in long-term preoccupation, like making the same sushi every day for 75 years. Rather than see a crossword game as a trifle, a distraction that will be replaced soon enough by a letter game or a colored tile game or a cow clicking game, what if we assumed just the opposite: that any particular game is worth playing for a lifetime, at least in principle, and therefore that every game is also worthy of infinite design refinement?

When we talk about game design like this, mathematically deep games come to mind first, games whose naturally designed properties result in an enormous solution spaces. Games like go, chess, and StarCraft. These games are sublime, but they are also scarce -- as perhaps they should be. Everyone should not be fated to search for the unicorn.

When we talk about game design like this, mathematically deep games come to mind first, games whose naturally designed properties result in an enormous solution spaces. Games like go, chess, and StarCraft. These games are sublime, but they are also scarce -- as perhaps they should be. Everyone should not be fated to search for the unicorn.

It's a less exotic but perhaps a nobler task to pursue a better and better take on a proven idea. Games like chess and go persist because they are old and mysterious enough to have hypostatized into legend. Games like Scrabble are a little different: invented in the modern era, they have identifiable designers and defensible copyrights. They've been commercialized and licensed within an inch of their lives, and as a result they're household names.

They're also static. Dead, almost. Scrabble doesn't change much, even when it gets adapted for computer. It can't: to do so would be to give up the stability that protects it. But digital games have a natural excuse to exceed their original boundaries, especially in today's era of digital downloads and constantly recycling hardware.

The materials from which computer games are made have always been pliable, but the products themselves have been fixed for physical distribution. Consoles, computers, screens, and handheld devices once remained relatively stable for long periods, whereas now they change their internal and external features and abilities almost too often.

Normally, these infrastructures underwrite a designerly attitude of short-term techno-fetishism: do what's necessary to exploit whatever's new while biding time until something else is new. But perhaps when pushed to extremes, obsolescence flips into commitment: when things change fast enough, there's no choice left but to eschew blind novelty in favor of incremental refinement.

This isn't anything new, really -- some games already live long through constant change and update, social games among them. Zynga even has a term for it: "cadence", the process of continually adding new features and mechanics to a game. FarmVille has cadence, and so does Madden NFL, albeit of different sorts.

At its worst, cadence means the soul-killing grind of a new feature a week, and that's mostly what we find in today's social game design practices. But at its best, a cadenced approach to design works slowly and deliberately over the long haul, rather than hot and fast for a short sprint, before the next thing offers new distraction.

Words With Friends is a good candidate for such treatment because it has a foot in both worlds: a digital game drawing from board game traditions but translating them into the weird, uncertain waters of Facebook, mobile, and whatever might emerge next to and beyond it.

The first step would be easy: remedying the obvious flaws and foibles in the current game. For example, the onboarding and app launch/restore process is far less elegant than it once was. The need for proper account registration was probably inevitable, but until recently Words With Friends would freeze on launch or reactivation to communicate with the network, undoing some of its earlier convenience as a pick-up game given a few minutes' distraction.

And there's no excuse for the game's ongoing unwillingness to preview the score of a placed word -- computers are pretty good at adding, after all.

But some seemingly obvious flaws might not be, when seen from the perspective of longevity and evolution rather than short-termism. Cadenced game design is a process of designer and player co-discovery, not just agile development efficiency. It's a process of building a durable cultural form as much as a stable product.

Take the Words With Friends dictionary as an example. It's terrible -- rudimentary and incomplete, failing to recognize common words, plurals, tense changes, and other inflections. No serious player will fail to encounter this limitation, but that doesn't make it a game design problem, exactly. After all, a limited dictionary might be a welcome play constraint; for example, Scrabble's rules prohibit abbreviations partly to reduce the number of viable two-letter plays (often key to expert play). Rather, the dictionary could be seen as an opportunity with many possible solutions.

Words With Friends could strive to offer the most complete word game dictionary around. That could take place through the use of a better dictionary, or through continuous updates, or even by using human computation to suggest and validate rejected words that should be included.

Or, if its creators really wanted to embrace Zynga-style monetization, the Words With Friends in-game store (did you even know it existed?) could sell custom dictionary add-ons: Disney/Marvel, Election 2012, Particle Physics, Molecular Gastronomy, Proust -- whatever.

Or, following Draw Something's model, Words With Friends could release limited edition collections of words, keyed to current trends or events. Like in Bookworm, these words might offer a bonus if played in a particular game. No matter the case, the dictionary's shortcomings suggest many possible avenues for future development, not just one obvious solution.

In fact, the dictionary reveals another of the game's quirks: while Scrabble is a game about knowing words, Words With Friends is a game about finding words. Thanks to the game's lack of penalties for plays that don't find a match in the game dictionary, players can try out endless possible combinations of letters until one of them works. The game's asynchronous nature tends to magnify this play pattern; none of the social anxiety of long turns exists in a distributed play session. And besides, each player has his or her own private screen for play, thus making it possible to hide experimental moves in a way that wouldn't be possible on a coffee table.

What to do with this unexpected situation? One answer would be to revel in it. Zach Gage's indie word game hit SpellTower features word-finding as a core mechanic, eschewing both time constraints and vocabulary exertion in favor of an open invitation to try as many hypothetical moves as possible before committing to one. But Gage -- who admits that a hatred for traditional word games partly motivated SpellTower -- had to devise a completely new design to offer an experience based on finding words over than manufacturing them.

Instead, Words With Friends might embrace its encouragement of word discovery, but add orthogonal elements to downplay its tendency to take over games among well matched, mid- to high-level players.

Instead, Words With Friends might embrace its encouragement of word discovery, but add orthogonal elements to downplay its tendency to take over games among well matched, mid- to high-level players.

One answer already exists in Zynga's other mobile hit, Draw Something, which demonstrates every stroke of a player's entire drawing while presenting the result to a competitor. This revelatory experience is certainly part of the excitement and appeal of the game, but it also serves a design purpose, implicitly challenging players to guess a drawing as early in its creation as possible (even though the game offers no explicit rewards for doing so).

A similar approach might be possible in Words With Friends, but with the opposite result. By storing and displaying all of a player's trial moves, including loose tiles placed on the board experimentally as well as word "guesses" rejected by the dictionary, an player would gain a partial view of an opponent's tiles, as well as his or her placement penchants.

Thus, a balance could be struck between the boundless experimentation the game currently allows and the closed, touch-play effect of traditional tabletop Scrabble. Discovery would still be possible, but in a form dampened by revelation.

Or, Words With Friends could fully embrace word discovery, making it a more central part of the game. Such a result is harder to imagine, but not impossible. For example, EA's mobile edition of Scrabble offers a hints system, which automatically selects the best word on the board.

This solution may go a bit overboard, as successes like a seven-letter "bingo" really ought to be limited to player accomplishment. Still, you can imagine a version of Words With Friends that might highlight words of a specific length crossing a particular tile, playable over a particular bonus, or in a particular region of the board, inviting controlled experimentation. Such invitations could simply offer hints, or they could come with bonuses akin to those suggested earlier for special per-match words.

For players and game owners alike, one of the benefits of asynchronous mobile games is their tendency to encourage multiple simultaneous sessions. Because moves are finite and not terribly time consuming, and because a player cannot regulate the play schedule of his or her opponents, it's common to start up many games at a time in a title like Words With Friends.

But unlike traditional Scrabble or Boggle, there's no way to distinguish players from one another by ability. When I play Words With Friends with my wife, I can play at the top of my ability; we're well matched competitors. My son is very good but I still beat him every time. But my daughter doesn't stand a chance against me; she just plays the first word she sees.

As with chess, in competitive tournament Scrabble, players are ranked by ability and matched accordingly. Establishing formal rankings and handicaps for Words With Friends might be appropriate if it evolved into a highly competitive quasi-sport, but for now such action would be premature.

In the meantime, there's still considerable opportunity to tune the game to make unmatched matches more enjoyable: the prohibition of two-letter word plays, algorithms more elaborate than mere randomness for letter distribution, play clocks, or any other number of variations that could find their way into individual matches on an ad-hoc basis.

Such additions might increase the satisfaction of individual players or reduce atrophy between partners willing to play but frustrated by a difference in ability or commitment. They might also re-awaken interest in the game among players who had put it down in favor of once-new alternatives.

Opposition to any of these design suggestions would likely appeal to simplicity: Words With Friends is a lithe take on a classic crossword board game, and adding jillions of extra configurable features only muddies the waters and turns players off. But some game design patterns don't evolve through winnowing and refinement, and Words With Friends might be a game whose long-term design evolution arises from complicating rather than simplifying its experience.

After all, people don't still play StarCraft because it reduced the real-time strategy game to wabi-sabi austerity, and they don't still play Madden because it narrowed its design down to local minimum of video game football. There's beauty in elegance and simplicity, but there's also beauty in convolution and elaborateness. Perhaps our industrial obsession with modernist minimalism has blinded us to the equal, if different beauty of the baroque.

Furthermore, what if the apparent market correction in the social games space suggests that a fundamental development pattern of the last half-decade -- fast ramp up, fast cadence, burn and cannibalize -- turned out to be just the pyramid scheme its critics feared? Even if we were to adopt the tech startup ideal of fast growth at all costs, once a product succeeds at establishing traction, doesn't it make sense to dig down deeper and ask how such a success could be made even more successful, rather than chasing ghosts? And doesn't it make even more sense to do so when follow-ups have been proven less successful than the original, as in the case of Zynga With Friends' post-Words asynchronous mobile roster?

There's an anxiety about such an idea. Game design purists privilege design innovation over all else. Technology purists privilege new devices, computational capabilities, and modes of play. Simultaneously, critics within and without the industry mock video games' tendency toward rehashing the same games in the same genres over and over again. What could be worse in the eyes of a novelty-obsessed public than working on a particular title for years, decades, even a lifetime? To make it better, yes, to dig deeper into its design space, sure, but also because it's gratifying and sustaining to work on something with long-term prospects.

As the social game industry "corrects", as the market analysts would put it, some of the hubris, excess, and trespass of social games will slough off like dead skin -- not necessarily because those practices will seem wrong in retrospect, mind you, but because they will no longer sustain the fast growth leveraged speculation demands.

As for Zynga, it seems to be responding by treating its successful games as raw materials best put to use elsewhere. Draw Something was licensed for a television game show, but Words With Friends is becoming a promotional platform. In addition to a deal with Hasbro to create a board game edition of the title (with mobile phone slots in the tile cradles, even), the game's latest digital update adds a complex celebrity tournament with attractive Hollywood stars and corporate sponsors. That's certainly one answer: treat video games as mere kindling for larger transmedia bonfires. Given such an option, the soul-killing grind starts to seem like a downright charming alternative. At least it focuses on making games rather than making fodder.

Still, we ought to be careful not to throw the snakeskin out with the snake, so to speak. In its positive incarnation, cadence might be the best lesson to take away from social game design, even if needs considerable revision to escape its legacy as an entrapment technique. A cadence is a rhythm, a pattern that keeps something going. For runners and cyclists it's a measure of gait, the number of steps or crankset revolutions per minute. A drum cadence or a military cadence keeps time, offering a beat to marching musicians or soldiers.

A cadence isn't just something you can measure because it keeps going, but a practice operating at a pace such that it can be kept going. Cadenced game design can be a type of sustainable game design, one capable of producing and reproducing a particular game by keeping it going, refining it, changing it, updating it. For a long time. Forever, perhaps.

I'm not sure if Newtoy wants to make Words With Friends forever. I'm not sure EA Tiburon wants to make Madden forever, either. But that slow, deliberate exploration of what a game can be, what it can do, and how it can be shaped in the hands of its players and designers over a very long time -- that's a virtue, and an unsung one.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like