Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Most games let you change things on screen. But how about the real world? Writer/designer Ian Bogost looks at Pain Station, World Without Oil and an RPG piggy bank to explore games that affect our everyday lives directly.

[Most games let you change things on screen. But how about games that make changes in the real world? Writer/designer Ian Bogost looks at Pain Station, World Without Oil and a role-playing game piggy bank to explore games that affect our everyday lives directly.]

Playing a video game is usually something we do outside of our everyday lives. As with any medium, our experiences with video games can influence how we think about our real lives, whether now or in the future. But when we play games, we take a break from that life. Playing a game is different from sorting digital photos, filing business receipts, or responding to email.

The same is true for so-called serious games. A corporate training game or an advergame might be designed to serve a purpose outside of the game -- learning how to implement a fast food franchise's customer service process, or exploring the features and functions of a new mobile phone, for example.

But even so, playing the game isn't the same thing as fielding customer complaints at the taco hut or managing appointments in the mobile calendar. Doing those things requires leaving the game and re-entering the real world.

There is power in using games as an "act apart," to use one of Johan Huizinga's terms for the separateness of play. When games invite us inside, they involve experimentation, ritual, role-playing, and risk-taking that might be impossible or undesirable in the real world. When video games take over our television screens or black out our computer desktops, they act as portals to alternate realities.

In short, when we play games, we temporarily interrupt and set aside ordinary life. And that's not really anything unusual. We do the same thing when we curl up in an armchair with a novel, or when the lights go down in a theatre, or when we plug in our earbuds on the commuter train.

But, in other media, immersion in a world apart is only one of many modalities. We don't just read novels, we also read road signs and sales reports and postal mail. We don't just watch film or television, we also watch security monitors and focus group recordings and weather reports. We don't just listen to music, we also listen to telephone ringtones and train chimes and lullabies.

In these cases, when we interact with the writing, or the moving images, or the music, we simultaneously perform or experience an action, be it work, play, or something mundane and in-between.

Philosophers and linguists sometimes distinguish between different types of speech. One such distinction contrasts speech acts that describe things from those that do things.

Philosopher of language J.L. Austin called the kind of speech acts that describe things constatives. Most ordinary speech falls into this category: "Roses are red, violets are blue."; "I wish I were Zorro."; "Finishing all his kale so reviled young Ernesto that he lost his interest in the éclair." These acts describe the world but don't act upon it.

"Performative" is a name for speech acts that do things themselves when they are uttered. The classic example of the performative is the cleric or magistrate's declaration, "I now pronounce you man and wife." In this case, the utterance itself performs the action of initiating the marriage union.

Other examples are promises and apologies, christenings and wagers, firing and sentencing. "I promise to come home by midnight"; "I dub thee Sir Wilbur"; "You're fired!"; "I bet you $100 I can beat Through the Fire and Flames on Expert." When we utter such statements, the act of speaking itself issues the commitment or regret, the naming or the bet.

In every video game, players' actions make the game work: tilting an analog stick to move Crash Bandicoot; pressing Y to make Niko Bellic carjack; strumming the fret of a Rock Band guitar to puppet the on-screen guitarist. Such is the definition of interactivity, after all. But there is another, rarer kind of gameplay action, one that performs some action outside of the game at the same time as it does so in the game.

The notion of the performative offers one way to understand such actions. In these cases, things a player does when playing take on a meaning in the game, but they also literally do something in the world beyond the game and its players.

On first blush, exercise games seem like an obvious example. In a game like Wii Fit, the player exerts physical effort to play, such as balancing on one leg or doing a push-up, the aggregate results of which improve her physical condition over time.

The same is true for physical performance games. In Dance Dance Revolution, the player moves around in a way that not only approximates dancing, but also demands physical exertion. Such games clearly accentuate the aerobic potential of video games and their immediate effects on the body.

But exergames also offer only a limited example of performative play, since the action performed in such games refers only to the player, and does so in an incremental way. When a bride says "I do" at the pulpit, she enters a new state of commitment completely and immediately. But when she performs a push-up on her Wii Balance Board, no particular state of fitness arises; it happens little by little, over time, in ways that each push-up can't fully explain.

In Austin's terms, a performative has to be complete to be considered an earnest one (he calls them "happy performatives"). Stronger examples of performative physical interfaces would act upon something more completely, and they would also have the potential to act on more than just the player herself.

Consider the Pain Station, a game installation created by German artists Volker Morawe and Tilman Reiff in 2001. Pain Station is a variant of Pong in a cocktail-style arcade cabinet. Two players compete by controlling a paddle with a knob in the usual fashion. The other hand must rest on a metal sensor, completing a circuit to enable the game.

When a player misses a ball, it contacts a pain symbol corresponding with one of three different types of pain: heat, electric shock, and flagellation. As each power up passes the goal line, the corresponding pain is inflicted upon the player by means of a heat element, electric circuit, and leather lash built into the table. The first to remove his hand from the sensor loses the game.

Morawe and Reiff have called Pain Station a video game adaptation of the duel. Although the outcome is less dire than a bout of pistols, the Pain Station means business; a web search reveals a cornucopia of ghastly injuries sustained by Pain Station combatants. Like the duel, Pain Station serves as a test of honor or a challenge of champions. To do so, its participants literally perform violence on an opponent by means of the game.

Another place to find performative play is in mixed reality games that couple computational interaction to real-world interaction in deliberate ways.

There are many genres of such games: mobile games, ubiquitous games, pervasive games, alternate reality games (ARGs) are among them. But not all of them necessarily involve performative play. A handset game played in a train or a puzzle game played by GPS hardly alters the state of the world through play alone.

The ones that do focus on game actions whose meaning and effect are layered, such that the same act has an in-game and out-of-game function and outcome. Furthermore, the meaning of the one often seems to inform or determine that of the other.

Cruel 2 B Kind, created by Jane McGonigal and myself, is a mobile phone-controlled real-world adaptation of the popular live-action roleplaying game Assassin. Instead of using water pistols or the other faux weapons common to Assassin, Cruel 2 B Kind's weapons are acts of kindness: compliment a person's footwear; wish them a pleasant day; perform a serenade for them.

Cruel 2 B Kind, created by Jane McGonigal and myself, is a mobile phone-controlled real-world adaptation of the popular live-action roleplaying game Assassin. Instead of using water pistols or the other faux weapons common to Assassin, Cruel 2 B Kind's weapons are acts of kindness: compliment a person's footwear; wish them a pleasant day; perform a serenade for them.

The game is designed to be played in groups within bounded urban environments among pedestrian populations. Since the participants are not revealed before the game, part of the experience involves deducing who is and who is not playing.

In the process, it is common to compliment or serenade ordinary folks going about their daily business. In such cases, well-wishes still function normally, bringing surprising but harmless pleasantry to people caught in the game's crossfire.

Another mixed reality game with performative results is ITVS's World Without Oil, an ARG about a global oil crisis created by Ken Eklund and Jane McGonigal. To play, participants created stories about their imagined strategies to get through daily life during an oil shortfall. Some wrote or recorded hypothetical accounts, while others literally enacted oil-saving strategies like planting community gardens or starting carpools. Doing so contributed to oil conservation in real ways, even if small ones.

Carnegie Mellon computer scientists Manuel Blum and Luis von Ahn's human computation games offer a very different example. Now aggregated at gwap.com, the best known is probably the ESP Game, in which two remote players see the same image and try to guess words the other would use to describe them.

As the game finds a match, it not only rewards points but also stores the matching terms as descriptive tags for the images. Google has even licensed the game (as the Google Image Labeler) to train its image search algorithm. Other Gwap games work similarly: Tag a Tune for identifying music, Squigl for identifying object positions within images.

In Cruel 2 B Kind and World Without Oil, the reality mixed into the game is physicality. In the Gwap games, the mixed reality is labor. Their gameplay performs a kind of work that's hard for computers but easy for humans. When players partake of the ESP Game, they perform the tagging of images directly and simultaneously with every move in the game. Here, gameplay resembles the performative act of christening a ship or a building.

That said, there is something "unhappy" in Austin's sense about Gwap's performative play: unlike World Without Oil or Pain Station, it fails to reveal and contextualize the meaning of its actions. Players may have some sense that the games contributes to image or music tagging, but they do not understand the implications of such actions in the way they understand promises and wagers when they perform such speech acts. This defect raises ethical concerns as much as formal ones.

When a game performs an action without the player's understanding of its implications, it confuses performativity and exploitation. "I do" is a meaningful performative utterance because bride, groom, and witnesses all fully understand its implications.

But the possible implications of image tags, for example, as tools for surveillance as much as for image searches, are not made obvious by the ESP Game. "Gwap" is an acronym for "Games with a Purpose." But a purpose is not enough to describe performative play. A context and a convention is also required.

Ethical matters notwithstanding, exercise, kindness, oil conservation, and metadata gathering are far more dramatic actions than many things done though other media. Restroom signs and rear view cameras are useful tools, but they are also mundane ones; people need to find toilets and avoid tricycles. Performative play in games can address more mundane activities like these as well.

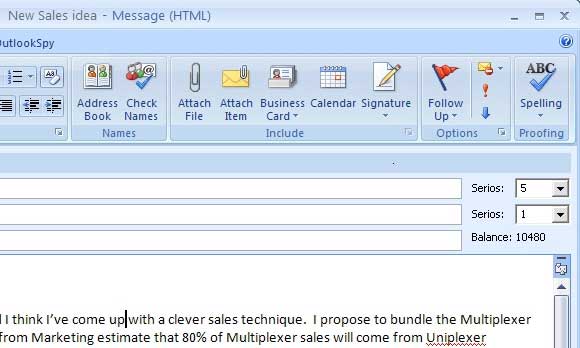

Consider enterprise solutions start-up Seriosity's product Attent. The premise is this: we all get too much email, which reduces productivity. In large organizations, much of this email is sent internally. The attention cost of receiving email doesn't match that of sending it. Things just get worse as the recipients become more senior, and therefore their time more valuable. Time management isn't the answer; less email is. And one way to reduce the email people receive is to make it more precious to send.

Attent tries to do exactly this, making email more expensive to send, or at least making workers more deliberate about how they do so. Since attention cost rises with seniority and expertise, email can be recast as an attention game: the CEO's attention costs more than the junior manager's, so the latter should have to "pay more" to get the attention of the former. And likewise, a senior executive would take a request from a junior one more seriously if the latter had to spend more of her scarce attention capital to obtain it.

Attent turns attention into capital, literally, via a scrip currency called Serios. Workers can get Serios by accepting email with attached payments, or companies can choose to dole it out in other ways as incentives or rewards. Attent works as a plug-in for the popular corporate email client Microsoft Outlook, so it's possible for workers to track their credits along with their calendar and even to sort email by their value in Serios rather than by date.

Office politics feels like a game because it involves many unpredictable, intersecting decisions that recombine in complex ways. Office work often involves strategy and planning, but it all happens behind the scenes, off the time clock. Attent puts that work back on the books, but invites rather than hides the social rules that drive office work.

For example, a group of lower-level workers can aggregate their attention capital by amassing Serios-filled emails to one another, whose loot a representative can then use to get attention up the chain. Attent tightly couples the workplace and the workplace game, such that "moves" in the game correspond closely to direct action in the workplace.

The Grocery Game offers another example of more mundane performative play. A web-based service provides data on the cheapest goods at local supermarkets, as well as tips on saving money on groceries through bulk purchase strategies. The goal of the game is to reduce one's family grocery costs as much as possible.

Implied sub-goals like turning a $100 grocery bill into a $5 one through extremely efficient uses of coupons and specials drive competition and community. In The Grocery Game, the act of play, shopping, and saving compress, such that the first action enacts the latter two. Through very tightly coupled performative play, Attent and The Grocery Game show how some games have more in common with doorbells and exit placards than immersive fantasy worlds.

Tomy's forthcoming Bankquest piggy bank turns The Grocery Game on its head, making the savings drive the play rather than vice-versa. Bankquest is a piggy bank for kids with a tiny digital role-playing game built into the front.

Tomy's forthcoming Bankquest piggy bank turns The Grocery Game on its head, making the savings drive the play rather than vice-versa. Bankquest is a piggy bank for kids with a tiny digital role-playing game built into the front.

Coins dropped into the bank become savings in the ordinary sense, but they also get translated into currency in the game, which can be used to buy items like weapons and armor.

Here the performative play is even more tightly coupled with the action it performs: filling the in-game wallet simultaneously fills the real one. And kids still get to spend the money they save.

Video games often face a challenge: what does playing a game do to people in the world? In the case of entertainment games, such a question asks about the effects of violence on players, or about how players find and evaluate meaning in games.

In training, advertising, and learning games, the question asks how players take knowledge they learned in a game and apply it in their daily lives. The motivational (and compulsive) aspects of games suggest other ways gameplay can influence behavior. But such matters cover only part of the intersection between our game lives and our ordinary lives.

In speech, performatives function because people understand both the meaning of the words they utter and the actions they cause. Austin suggests that performatives make conscious actions explicit; this is why making a promise works. Likewise, in games that feature performative mechanics, the performance and the play are both known to the player, and their implications are simultaneous and immediate.

Performativity in discourse produces action. Performativity in video games couple gameplay to real-world action. Performative gameplay describes mechanics that change the state of the world through play actions themselves, rather than by inspiring possible future actions through coersion or reflection.

But there is an important distinction to note between performative play and more generic real-world effects. As examples like Wii Fit and the ESP Game demonstrate, performativity is a special kind of play that for which outcome alone is an insufficient criterion. In addition, the player's conscious understanding of the purpose, effect, and implications of her actions, such that they bear meaning as cultural conditions, not just instrumental contrivances.

---

Pain Station photo by Ultimaratiopharm, used under Creative Commons license.

Cruel 2 B Kind photo by Kiyash Monsef, used under Creative Commons license.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like