Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Just what will the achievementization of the world mean? Author and game designer Ian Bogost ponders Jesse Schell's DICE talk and blends his interpretation with research. Will it work... and, more importantly, is it good?

[Just what will the achievementization of the world mean? Author and game designer Ian Bogost ponders Jesse Schell's DICE talk and blends his interpretation with research. Will it work... and, more importantly, is it good?]

In a widely disseminated talk at DICE last month, Carnegie Mellon University Entertainment Technology Center professor Jesse Schell made a provocation: can game-like external rewards make people lead better lives?

To answer the question, Schell explored hypothetical scenarios that might combine awards of Xbox Achievements-like scrip with emerging sensor networks that would track our everyday behaviors. Teeth brushing might earn sponsored awards from Crest, for example, and taking the bus might earn awards from a government mass transit program.

Sounds farfetched? Schell points out early signals that support his vision, including the dashboard of the new Ford Fusion, which features an image of a plant that flourishes or droops based on how efficiently the driver pilots the vehicle.

Reactions to the talk have been mixed, with some heralding him as a brilliant oracle of a desirable future, others wondering how he could have failed to mention related, high-profile work by Frank Lantz (Area/Code) and Jane McGonigal (Institute for the Future), and others dismissing Schell's prophesy as dystopian nightmare.

Here, I want instead to explore a few philosophical problems that arise from Schell's position -- problems which proponents and detractors should both consider.

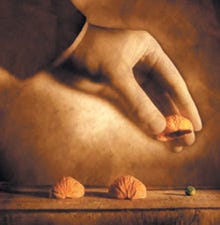

In addition to his professorship at CMU, Jesse Schell operates a game studio. They make electronic and location-based entertainment, under the shingle "Schell Games." It's a clever name, because it plays its founder's surname off a well-known gambling game, the shell game.

Everyone knows it: a small ball is hidden under one of three walnut shells. The operator shuffles the shells around quickly, and a player is made to guess which shell houses the ball. Wagers are usually made, and indeed a typical run may appear to draw in a great many bets around a makeshift table on a street corner.

But the shell game is not a game of chance at all. It's a confidence trick. A skilled operator can remove and replace the pea at will, insuring that the player only wins if the operator chooses (which he might do in order to encourage additional bets). Most of the audience is in on the swindle, and their bets serve to encourage a target to place (and then ratchet up) the wagers. The shell game is not a game at all. It's a fraud, a swindle, a con.

But the shell game is not a game of chance at all. It's a confidence trick. A skilled operator can remove and replace the pea at will, insuring that the player only wins if the operator chooses (which he might do in order to encourage additional bets). Most of the audience is in on the swindle, and their bets serve to encourage a target to place (and then ratchet up) the wagers. The shell game is not a game at all. It's a fraud, a swindle, a con.

With apologies to Mr. Schell's good name and studio, we might give the title schell games to video game incentive tricks that cause people to "do the right thing," such as brush their teeth or drive their cars efficiently. (I'll spell it in the lower case to distinguish the type of game from Jesse Schell's company.)

Just as the shell game dupes players into believing that they are making wagers against chance, so the schell game dupes players into believing that they are completing virtuous actions toward righteous positions.

When seen from the perspective of their outcome alone, a wager in a shell game looks like an earnest gamble. But when seen from the perspective of the operator, who is altering the game to suit his desired outcomes, the wager is merely a foil to be used against the player.

Likewise, when outcomes alone are considered, an action taken in a schell game looks like an earnest honor. But when seen from the vantage point of the agents who dole out incentives, that honor again becomes merely a foil to motivate an action.

In a response to Schell's talk, game designer David Sirlin urges you to "Brush your teeth because it fights tooth decay, not because you get points for it."

In this entreaty, Sirlin makes a distinction between outcome and motivation. Sure, brushing one's teeth might prevent tooth decay, but brushing one's teeth for points subordinates tooth decay so much as to make it invisible.

I'll put it more strongly: when people act because incentives compel them toward particular choices, they cannot be said to be making choices at all.

In my book Persuasive Games, I make this same objection to the concept of "persuasive technology," a general approach to using computing to change people's actions advanced by Stanford researcher BJ Fogg and others.

A typical example of such an approach might deploy disincentives instead of incentives. The checkout system at Amazon.com and other web retailers tunnels a buyer from product to purchase by removing all links from the page. A hidden camera system captures images of drivers who exceed the speed limit, and a computer automatically issues a fine.

In such cases, the buyer has not been convinced that a product or seller is desirable, nor has the driver been persuaded that speeding on a particular route is dangerous and should be avoided for reasons of public safety.

To be persuaded, agents must have had the opportunity to deliberate about an action or belief that they have chosen to perform or adopt. In the absence of such deliberation, outcome alone is not sufficient to account for peoples' beliefs or motivations.

But who cares about deliberation if we get the results we want? If achievement-like structures can get kids to brush their teeth or adults to exercise more, why does one's original motivation matter?

Because to thrive, culture requires deliberation and rationale in addition to convention. When we think about what to do in a given situation, we may fall back on actions which come easily or have incentives attached to them. But when we consider which situations themselves are more or less important, we must make appeals to a higher order.

Otherwise, we have no basis upon which to judge virtue in the first place. Otherwise, one code of conduct is as good as another, and the best codes become the ones with the most appealing incentives. After all, the very question of what results we ought to strive for is open to debate.

There's a concept in ethics known as moral luck, most clearly described by Bernard Williams and Thomas Nagel in the late 1970s.

Here's the classic example: two drivers make their way down two identical roads at identical times. In both cases, the drivers look down to change the radio station or answer a cell phone, and in that moment of distraction each runs a red light.

In the first driver's case, an old woman had just stepped off the curb to cross the street, and despite the fact that he tries to avoid her, the driver can't stop in time. His car strikes her down and kills her. In the second driver's case, there is no old woman, and therefore no consequence other than, perhaps, a traffic ticket.

Williams points out that we tend to correlate the action with responsibility in moral judgements. Thus, we would likely judge the first driver to be more morally guilty than the second driver.

But there's a problem: the difference between the drivers' moral states actually has nothing to do with choices under their control. It is entirely a matter of luck. In one case, an old woman happened to be crossing the street, in the other she didn't.

Nagel calls the above kind of situation resultant moral luck. In such cases, luck affects the consequences of actions, making it difficult to judge them as worthy of praise or reproach.

Schell games are games of resultant moral luck. When one responds to game-based incentives like points and rewards, good things might happen: better hygiene, or a cleaner environment, or a greater connection to one's family. But these results cannot be judged to have the same moral responsibility as choices made given factors under greater player control.

Consider a Facebook game like Farmville by Zynga. In the game, players can recruit friends to found neighboring farms. Indeed, playing well almost requires it. Visiting and helping on these farms yields money and experience points, but with enough neighbors, players earn the ability to expand their own farms.

You can run the moral luck test above on Farmville, replacing drivers with players, and vehicular manslaughter with friendship. Is a player of Farmville developing and invigorating friendships through play, or is the player exploiting those friendships for positive gain?

There's no simple answer, of course, but moral luck makes it difficult to judge this so-called social play with a moral compass, as an expression of the virtue of fidelity or affection when that affection may or may not have arisen from play. What is internal to the game and what is external? The answer is murky.

There's one final problem with schell games, and that's this: games are not primarily comprised of incentives and rewards in the first place, not even the more unusual ones Schell presents in his talk. The heart of games is not points, but process. Games have the capacity to persuade us because they can depict perspectives on how things work, and they can give us insights into the complex and often ambiguous connections between them.

At their purest, schell games want to strip process from games, putting simplistic incentives its place.

In this respect, the most ironic example Schell presented in his talk at DICE is that of the Ford Fusion dashboard. The growing plant in the dash holds promise not because it offers an incentive to drive in a fuel-efficient manner, but because it reveals the combinations of mechanical, electrical, and combustive processes that lead to fuel-efficient driving.

The Fusion driver does not jump with Pavlovian delight upon seeing a lively fern, but noodles with intrigue over the combinations of traffic patterns, driving, techniques, topology that lead to different results. She might ask questions like "Why does driving a certain way have an impact on fuel consumption," and "How are neighborhoods and cities designed to encourage and discourage such driving?"

She might wonder how the automobile and urban planning codeveloped over time, and as a less fuel-efficient vehicle honks angrily from behind, she might consider the legislative, social, and cultural processes would need to change in order to bring about a different cultural attitude toward fuel consumption.

Instead of revealing the processes that define values, schell games tend to hide them away, compacted into the ideologies of corporations and governments. In that regard, if Jesse Schell is right and such games are on the horizon, we ought to bear in mind a warning. When we ask the question what is worth doing through games, we'd better hope the operator is not a shill.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like