Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

With Lionhead's Fable II now released, Gamasutra talks to creator Peter Molyneux in-depth about the creative process behind the game, from 'white box' prototyping to live-action filming.

Lionead's Xbox 360-exclusive action adventure title Fable II has just debuted -- and to significant acclaim thus far, it seems.

And of course, the charismatic and talented -- if divisive -- personality at the center of this massive development effort is Populous and Black & White creator Peter Molyneux, whose Lionhead Studios developed the game, its first since it was acquired by Microsoft in 2006.

The grand ideas and inspirations get talked about a lot. But what about the actual processes used in creating the game? Gamasutra had a chance to speak with Molyneux during this month's Tokyo Game Show in Japan, and asked about the development process of the game, from white boxing and prototyping to high-level design; in a major reveal, Molyneux details the intensive process by which Lionhead formulated the story sequences in the game.

Gamasutra also discussed the then-breaking controversy over the possible exclusion of co-op play, a promised feature, from the shipped game -- and how stories like this can become massive, for a brief period, in today's media environment.

I do have one real question that I've been really interested to hear your reaction to. It was announced that the cooperative play would be added later, after the game shipped.

PM: That's not quite...

Please clarify.

PM: We thought this was a complete non-event. But let me explain why we thought it was a non-event. Because we're from the PC world originally, and of course you always patch PC versions, and we never intended not to do it for day-one ship.

When you're doing multiplayer, as you probably know, you need to get single player completely bug-free before you weed out the final bugs on multiplayer, because if there are any inconsistencies in the two versions when you're playing over Live, it just won't work. You end up trying to fix multiplayer bugs but you're actually fixing single player bugs.

So we got to the end of doing the single player game. It went into certification; it came out the other end. And we knew we had three weeks left just to weed out some of those final bugs in the multiplayer. And we greedily used that time. We always intended for it to be a day one patch.

We were totally mystified, in a way, that people got so upset and thought that we were taking features out of the game. And it wasn't that at all. The multiplayer is now in certification. It looks almost certain that it is going to be there for a day one patch. These things are never 100%, but we've never failed certification before. So I'm 100% certain that it'll be there day one.

I think you'll see this more and more. That the extra three weeks that you get when you don't have to manufacture disks, it's invaluable.

[Ed. note: The patch was completed and put up for download October 21, the day the game went on sale in North America.]

Most big games and probably even many small games have a Title Update the day you put the game in the drive, so it's nothing new. I think what it is, is that the broader question is, you said you're surprised to hear this reaction. Do you think that things got blown out of proportion? Or that people maybe not intentionally, maybe intentionally, misconstrued what was happening?

PM: Well I looked at a lot of the posts and some people were saying, and I can completely understand this, "Oh my God, it's happening again. We were promised features, and they're not going to be there." And with the heritage that I unfortunately gave Fable I, I can completely understand that.

And I just don't think we thought it through. And I think actually we should have waited a little bit longer and said, "Oh look, it's going to be a day one patch." But instead we were a little bit more diplomatic and said it may be a day one patch, which made people...

The PR cycles are getting -- the feedback loop is getting tighter and tighter and people are so plugged in these days that, even if a big story only lasts 24 hours, it'll create a lot of noise.

PM: Yeah. I know. It is. And in some ways it's quite exciting. It feels like you're on the edge of this whirlwind that could just blow up in your face at any time. And in other ways it's amazingly invigorating, in that, if you say something in an interview like this, to see people react.

Because normally, to be honest with you, I think I sit opposite you, and I think "Oh God, this must sound so bloody boring. I'm sure nobody's going to take any interest at all." And then when you get these explosions of interest, it is a fantastic feeling sometimes, when it goes well. You lose sleep when it goes badly, definitely.

Now that you're at the end, you've completed the game and submitted the multiplayer patch, how do you feel? I'm sure you feel relieved to come to the end of a project that was difficult, or challenging.

PM: It's a very, very odd feeling finishing a game. "Relief" is the wrong word. There's all the relief from people around you. The marketing people are relieved, and the production people are relieved, and the sales forecast people are relieved, and the people... they're all relieved.

I personally go into a grieving process. I do. It's like I have a month of grieving where my brain is no longer full of Fable. And I'm not thinking about, "God, what am I going to say about Fable, what am I going to show? What does this mean and what does that mean? And God, isn't it going to be fantastic to see people play it?"

It fills the whole of your mind, and then suddenly [claps] it's over. And you know, the cat is out of the bag. And you kind of miss it.

I'm sure.

PM: You miss it in way. I've never had a game that I've truly been proud of. And that sounds like this is a PR line of being humble. It's not. I always had this tradition of going into a shop and buying the retail copy and going home and actually playing it.

And I always play it, and it must be like watching yourself in a movie. I think, "Oh God, why did I make that stupid mistake?" And I hope -- I think -- Fable is going to be closer than any game I've done before to what I thought it was going to be when I first sat down to the idea.

Well, that brings me to something. I remember when I first met you in 2004, and it was right when you were finishing up Fable I. And you told me at that time, if I remember correctly, that you already knew where Fable II and Fable III were going to go. How close did you get in the end, four years later, to what you thought Fable II was going to be at that time?

PM: Well there's the thing to that. I think, when Dene and Simon Carter and I were talking about creating Fable, back when we were doing Dungeon Keeper together, we talked about this great vision, and it was more about the vision of the story, and what it would be like to play through this.

And that's perhaps what I was talking about there. And I also, perhaps, was talking about, God, there's some things I would have loved to have done better in Fable I.

Sure.

PM: At the end of Fable I, we sat down and we kind of thought, firstly the reviews were... some of the reviews were very mixed. We asked ourselves, "How did we disappoint people?" -- with those reviews.

The second thing, the boards were unbelievably passionate about some things. Incredibly passionate and very focused on, "Why isn't there free roaming? I thought there was free roaming, this should have free roaming, it's supposed to be an open world." That was 100%, everybody was passionate about that.

There were some other things that were very confusing. The length of the story was immensely confusing because a lot of people said it was far, far, far too short and a lot more people said, "Actually, it's just the right length, and it was the only game I finished because it was that length."

Yes. That could be a real challenge.

PM: Yes, and it was a real challenge. So we had this list of stuff which we went away and thought we're really going to try and fix that. We did, we really did do due diligence on that. I mean there is, when you've got that blank sheet of paper when you come to a new game, there's a lot of voices screaming in your ear trying to persuade you to take it in a different direction.

A lot of those voices are the science of making computer games. Those are the most scary ones -- is that you have these market research people -- and Microsoft is brilliant at doing this, to come in and say, "51.3% of your audience did this and 68.8% did that," and you end up thinking, "Oh my God, how am I ever going to design this?" It's like someone mixed together 20 jigsaw puzzles and you've got to make a picture out of those jigsaw pieces.

But, at that point, it became clear that the real failing of Fable I is that we didn't make a truly emotional experience that people remember. I've never... did you play Fable I?

Oh, yes. I played it in your office, remember?

PM: Yeah, I do remember. Did you finish it, though?

Yes, I got to the end.

PM: Can you remember the story?

I can remember what happened. I'm not sure that I would say I remember it like a story, in the sense that you remember the story from a movie.

PM: Exactly. That was a stupid, dumb mistake and you will remember the story of Fable II and I want you to remember the story of Fable II for the rest of your life. That is my job.

When you sit down at the beginning of the project and you... the undertaking of making a 360 game is a very complicated process, and there's a lot of thought on how to manage it, whether to do a lot of pre-design. A lot of people these days, and for very good reasons, want to be as reactive as they can be -- make things, test them, change them. How do you approach design these days, in this environment?

PM: Yes. I mean, that's one of the things that you learn, is that when you have got 100 people, you just cannot be that creative whirlwind anymore. You just can't walk into an office of 100 people and say, "I've had a really good idea, hey let's all do this for awhile".

Because it is all about the genius of planning out. There are people behind the scenes whose names you never hear, who are brilliant at planning out these terrible experiments that I give them.

Part of this process that we started off in Fable II was to say, "Right, we are going to experiment and we're going to take that experiment seriously, and we're going to have competitive experiments going on, and we're going to feel absolutely fine."

There's one rule in those experiments. Any experiment that was done, all the code and art would be thrown away, so you weren't burdened. A lot of the time you're burdened by the need to make things solid and sustainable and, "God, we're writing a piece of code now, and by the time we're finished it'll be three years old."

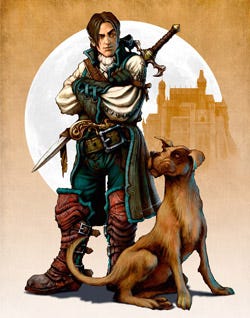

These experiments, we iterated around. The dog was an experiment, and the combat was an experiment, and the free roaming was an experiment, the breadcrumb trail was an experiment. There were many different iterations, and that is when the team is smaller and a lot more agile.

And then when you get to the end of those experiments you have to think about it, and say to yourself, "Right, I've got my list of ingredients. That is it. I'm going to make my game soup out of this list of ingredients. I'm not having any more. I can have more of this sort of ingredient and less of this sort of ingredient, but I'm not going to add a new ingredient."

That first experiment took about a year, and allowed the planners to plan out more consistently, into the rest of the project. What we don't do, a lot of the times, I think publishers have this term -- which I think is a totally invalid term. They say, "Are you in production?" We don't -- there isn't a sense of that, because sometimes you can't say that code is fully in production, because quite often, even though you've got these experiments, you know what you're doing; you're still putting something in and taking something out again because it may not work, or may not work for this system.

Does that answer your question?

Yes. The question I have, just from a perspective of how you do it at your studio is, do you work with Fable I and use that as a prototyping environment or did you work with other tools?

PM: Yes, we did, and there was a lot of time where we sort of white boxed using the Fable I code. I mean, one of the problems that we did have which was a complete nightmare, is not having the tools to support the environments we wanted to create until very late.

There was a lot of white boxing, but you know, you can only do a certain amount of that white boxing. Sure enough, you can say, "There's a tree going to be here, and there's going to be a building here," but how far apart they are depends on how fast your hero moves, which depends on how fast your framerate is.

I mean, there's so many iterations that you go through. I could show you the white box world that was done in Fable I. You may recognize parts of it. But an awful lot of it does change.

We had a real problem, because we wanted to tell this story that you would remember. Normally, when we did Fable I, for example, the story actually didn't come together till the last three months, because you didn't have the regions. And you had to have the regions to have the voice stuff in.

And this was our problem. If we were to tell a truly great story we need to get script writers and directors, and gosh knows, and actors involved way before our world was even started.

So we did something which I think you are going to see more of, in this industry, called staging. What we did: We wrote the story. We got a script writer in. He wrote the script to the story.

Someone with a background in linear media?

PM: Yeah, in fact the guy who did it was called Richard Bryant, who's a smart, clever guy who doesn't mind working with an idiot like me. He literally would sit very calmly in the meeting while I ranted and raved about emotion, and then write down, and say "Right, then if you want the person to feel that, than this is the line that they need to say."

We did all that. We then hired what's called a sound stage. It was a huge vast white room. We got seven actors in. We flew in a film director from Hollywood who was experienced in doing some film work, but also experienced in teaching people to direct. And we acted out the entirety of the story of Fable II, within this white space. We had never done that before.

And what we found is that we could get to that [result we wanted]. You've got to put it in... It's got to be there before you know it's there. We got to that before we had to put it in the game. So the story, the narrative, the emotional points of the story were there, acted in this sound space.

Now, did you record that just for internal reference?

PM: Yeah. Because the problem is that when you've got a dramatic scene, you say to your scripters -- they're coders actually -- "Yeah, Okay, the hero is talking to Balthazar, and saying these lines."

The poor old scripters have no idea how to stage that. Should that Balthazar character be looking at you? Should they be walking over here? Should they be nodding their head? Should they be shaking their head?

So what we did is we filmed the entirety of that process. The actors ad-libbed all over the place which was absolutely fine -- because we rewrote the scripts again. And when the scripters went to put the script in the game, they watched the video. And just then, watching the video means that this was staged more far more easily.

[Molyneux demonstrates in the game, showing a scene with a guard speaking to the protagonist from atop a wooden gate.]

You see, this thing was staged. And, before we did the staging, this guy here [atop the gate] was down the bottom, here. And what happened was that people started trying to mess around with that guy, because this is right early on in the game when you've first gotten a lot of your abilities.

And people were trying to kill him and express to him, and not paying attention in the slightest way to what he was saying. But putting him up there meant that they didn't have to do that.

We would have probably got to the same conclusion by putting it in the game. But we would have done that in the last six months of development, rather than in the first six months of development.

So then did you re-record the dialogue in a studio later, the final version?

PM: Yes.

So you had the original version of the script. You basically, essentially workshopped it through this process? The writer took this version including ad-libs...?

PM: The ad-libbing. Everything was filmed. We re-wrote the scripts on the day, so some of the scenes took a whole day to... because there was so much ad-libbing going on. And, oh my God, you know, because there were two cameras the whole time -- for what your gamer's view was going to be, and what the cutscene could be -- because, as the player, you wouldn't have control of that.

And there were some other moments where you realize, "Jesus, you can't see his face!" You are over here [indicates screen] and you can't see what he's saying. Going back to it, there were some moments like that, where we had to iterate around.

And then at the end of that process we went away, rewrote the story again, and we went back into the studio again one last time, because there were some scenes that just weren't working, and then that was all put into the game.

Then we got the voiceover talent. And you have to work like that, because the voiceover talent here -- there's Stephen Fry and Zoë Wanamaker... and these are big name people.

You can't mess around with them and say, "Oooh! I don't know what you're going to say next, but just make something up!" And that's what we would have done in Fable I, probably.

You had your writer as integrally part of the process throughout?

PM: Yes, yes, yes.

Because very often when people are brought in it's, "Deliver me a script", and it just doesn't work, is the consensus, I believe.

Because very often when people are brought in it's, "Deliver me a script", and it just doesn't work, is the consensus, I believe.

PM: No, no, no. Absolutely not. In fact, Richard came over. He's American, but he came over and he lived in England for six months with his wife and children, and he was in every design meeting, because the game mechanics in Fable II... [Reaching for controller, indicating screen]

Because, this dog here. The dog is actually a game mechanic but he is part of the script and narrative as well. So he had to have an appreciation of that, you know, to write the script.

I had this fantastic moment yesterday. Because, you see, the other thing is, when you finish a game, you never meet anyone who has really played the final version.

You know, the testers at Lionhead, they're about as objective as a brick wall, because they have played it a thousand times and seen ten thousand bugs. So you never meet anyone who's actually played and enjoyed it.

And I was walking through the [Tokyo Game] show and there's quite a few people now who have played the game cheekily without waiting the final build, a lot of the regional people. These two people came up to me almost at the same time. And they'd played the game. And it was just fantastic to hear from their experience of the game. It really was. It was some fantastic moments. I actually got really emotional. It was quite embarrassing.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like