Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

A designer explains methodologies and philosophies behind personality generation in games.

Tanya X. Short is the Captain of Kitfox Games, the indie studio behind Moon Hunters, Shattered Planet, and the upcoming Shrouded Isle. She and Tarn Adams (Dwarf Fortress) released a Procedural Generation in Game Design textbook in June 2017, with chapters from leaders in the field.

Although it’s easy to find dozens of examples and tutorials of how to approach generating terrain, from caves to hillsides to entire planets, there are not many (yet) exploring how best to approach generating people and their personalities. The basic assumptions and techniques are still in flux and being established with every new algorithm.

When I first sat down to draw up a personality generation algorithm, it seemed overwhelmingly complex. How do you describe why someone has the beliefs, goals, virtues, fears, memories, and friends that they choose to? How do you turn a person into just a formula? This article will outline the ways in which Kitfox considers the problem of personality generation, for Moon Hunters, The Shrouded Isle, and other projects, in the hopes that your next project can benefit from our toolbox.

Personalities can be described as “patterns of behaviour and why we follow them”. They are often described as our true selves, and a key part of how humans understand each other – defining how we respond to crises and challenge. Without personalities, characters are uniform meatbags, without differing opinions, priorities, moralities, impulses, or preferences.

Before you start generating, ask yourself: what are the important differences and similarities across characters that your system should highlight?

In social circles, from Bronze Age firepits to MMOs, humans like to identify themselves and others as archetypes. By studying the common schematics used the last few thousand years, you might find a certain approach or structure suits your gameplay more than others.

Mythical: In storytelling, characters are often differentiated by a common language of symbolic personalities, including the Trickster, the Saviour, the Elder, etc. Many of these were elaborated and structured more formally by tarot, Shakespeare, Joseph Campbell, and others. The benefit of this bombastic approach is that character personalities are consistent, familiar, larger-than-life, and may only need to take 1 (melodramatic) action to be identified. However, a mythical roster of characters and plot arcs are necessarily limited, as there isn’t a lot of room for subtlety.

Virtues & Vices: The original modular personality construct-a- kit! Pick any two and combine them to form an interesting constellation of a person, whether your morality system comes from the modern day or fictional religions. The benefit of this approach is that it elegantly suggests a wider socio-political context (approval, disapproval), and sets up binary oppositions instantly. On the other hand, implying judgment of your characters may undermine more expressive, subtle stories.

Types: In astrology (Western and others) and Myers-Briggs, there can be 12, 16, or potentially more personality “types”, such as Leo, Rabbit, or INFP. These are often defined by sets of binaries; introversion versus extroversion, patience versus impulsiveness, etc. This allows for more complex oppositions and conflicts than strict virtues & vices, but may also be less easily modularized and communicated. If you want a lot of points of conflict, this may be your best paradigm.

Group Identities: Personality tests have gained popularity in recent years (What Hogwarts house do you belong to? What animal are you? Are you a nerd, jock, or goth?) partially because they allow us to re-categorize ourselves by similarities to others, usually based around common interests or moralities, further embellished by the power of stereotyping. If your game has groups of characters in conflict, defining the influence of stereotyping on your characters may be important.

Motivational: If you like measurable hard science, the “five factor model” personality theory from modern psychology (or six factor model cross-culturally) can be a great jumping-off point for designing characters. Although theoretically defined by 5 axes of binary opposition (openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism), studies using the theory offer insight into how education, health, romance, gender, and other influences statistically change the way we behave. If you’re aiming to create realistic mirrors of humanity, this sort of paradigm may be very inspirational.

In Moon Hunters, we took a mythic approach to lower expectations, better accommodate a generated world, and to resonate with traditional genre conventions. Plus, I personally adore mythology. However, in The Shrouded Isle, Jongwoo Kim is the lead designer, and he uses virtues and vices as pure reflections of social utility in an over- the-top cult setting, with some alternate perspectives on what constitutes “sin”. This will allow us to very quickly communicate which characters are valued by their community, and therefore more or less desirable as chosen victims of human sacrifice.

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

This list is only the very beginning of what you could spend a lifetime studying! Personality is at the core of the human condition, meaning it is of central concern to psychology, mythology, literature, anthropology, sociology, etc. If you have more contributions of paradigms, of course, feel free to comment.

Aside: Is This Necessary?

When I was a designer on Age of Conan, I enjoyed defining possibilities for costume variations – toga colors, optional accessories, etc, partially because they were very high value for very little effort. With just a few options, a few dozen distinct characters could appear to have different-seeming personalities (“this one has so much jewelry! He must be so vain! Ooh this one with a blindfold is mysterious!”). Names function similarly, such that Grognaw Soul-drinker might appear to have a different disposition and gender than Sheila Soft-paw, even if they are mechanically identical.

I include this as a note simply to state what might be obvious to experienced game designers: If your player has no way (or motivation) to observe the different behaviour patterns of your characters, the illusion of personality may be more effective than actual personality generation. Here in 2016, most commercially sold games do not have the kind of gameplay that warrants deep psychological modeling for non-player characters. Perhaps that will change in the future.

However, if dynamic personality generation is of sufficient value to your gameplay, let’s examine what your priorities and approach might be…

How do players see the personalities of characters in your game? What are the elements you can adjust to help the character express themselves within your algorithm? What are the variables?

Appearance (Character Design): Name, gender, race, height, body- type, fashion, posture, and default expression all factor into the player’s first impression of the character. Many of these will feed into stereotyped assumptions, which can then be used or subverted as you wish. In authored content, it’s common to include one visual marker that is consistent with audience assumption, making the character more relatable and accessible.

Behaviour: What actions does the character take? What reactions do they have to others? What are their habits, impulses, speech patterns, and mannerisms? In the Sims and Dwarf Fortress, they go so far as to display a character’s primary thoughts, which the player can then map into systems of preferences, regret, anxiety, gratitude, etc.

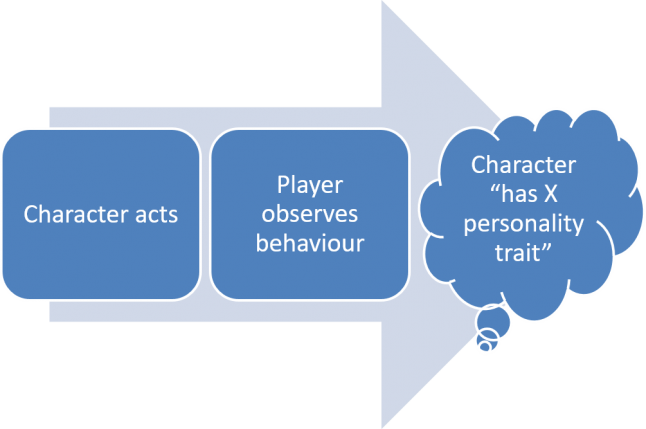

Well-written passive or linear media presents a character’s actions, then the user observes that character’s behaviour over time, and finally the user comes to a conclusion about that character’s personality, motivations, etc. You may have heard the phrase “show don’t tell” in writing circles – if the reader/watcher/player can discern the humanity of your world’s characters without you literally writing personality traits on someone’s forehead, you’re succeeding.

Thus, for example, in linear media, a character (such as Chie in Persona 4) who has an interest in sports may wear a tracksuit, signalling this interest immediately. This outfit could also suggest physical strength, energy, discipline, or other archetypes, depending on how the character is posed/styled, which can then be fulfilled or subverted as the player “gets to know” the character. But introducing the character as “Chie the Strong-Willed” would undermine this interpretive process that is part of storytelling.

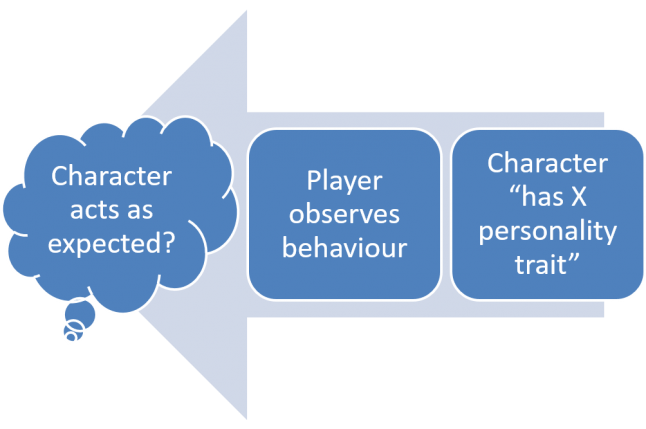

However, most procedural and interactive systems currently on the market (including The Sims, Crusader Kings II, and Dwarf Fortress) reverse this dynamic, exposing character traits up-front and then allowing the player to observe behaviour and compare their expectations to what the character does and how they appear. I believe this may be a symptom of players’ current relative illiteracy of procedural content, such that designers are under huge pressures to ensure their outcomes appear less “random” and to ensure the systems they build aren’t “wasted” in opacity from the player.

Thus, for example, in most generated-personality games at present, Chie would have “Strong- Willed” written next to her name. This would suggest various potential behaviours to the player, and perhaps encourage them to guide the character into sports – or the game itself might suggest dressing in a tracksuit for additional willpower. With experimentation and systemic exploration (common player activities in procedural spaces), the player will watch this character to observe for themselves how this personality trait influences their behaviour. When Chie returns several times to the treadmill, cheers you on, or resists temptation, this now has added meaning. Without the Strong-Willed cue, Chie’s behaviour might seem baffling, arbitrary, or even worse, buggy.

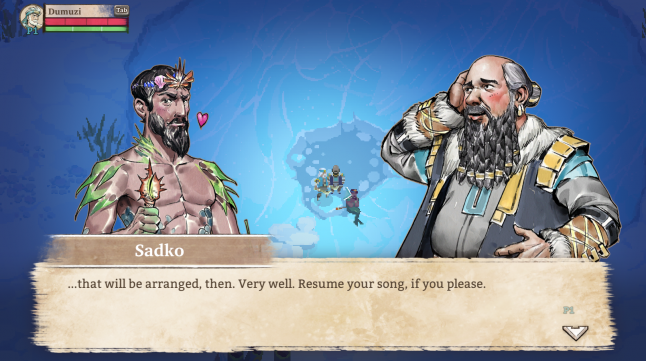

We combined the two a bit in Moon Hunters by collecting input from the player, reflecting a detected pattern back to the player as a descriptive/reactive mythic trait (such as Cunning, Seductive, etc), and finally predicting future behaviour in the form of a generated "legend" of their deeds, including how the character met their end (happily or otherwise).

However, we were in some ways hamstrung by the fact that we were trying to generate the player's personality -- we didn't have a good way to generate past behaviour, nor display future behaviour without taking away player control. In retrospect, perhaps we should have paid closer attention to generating the personalities of the non-player characters, which is a much more common approach.

If we had gone that direction, we would have had a few different ways we could have explored it: both in the inputs to generate a new personality, and the results of varying personalities.

From Halo to Crusader Kings, from Dwarf Fortress, to The Sims, from Civilization to Caves of Qud, I have found that "behaviour" is not a useful enough term, as it encompasses several different kinds of outputs, even when separated into proactive and passive/avoidant behaviours. This may change, but presently, I feel there are four major ways to generate character personalities:

Motivations: needs, wants, impulses, moods, over time forming "traits"/patterns. Someone who has the frequent impulse to punch walls is seen as having a different personality than someone who writes poetry about heartbreak.

Relationships: who we know, who we act on, who acts on us, levels of intimacy. Someone who has many close friends and lovers is seen as having a different personality than someone who socially disconnected, and can enact their personality differently on their environment.

Ability: verbs or vocabulary the character has access to/skill in. Someone who gives presidential orders can express their personality in different ways than someone who only runs a business.

Knowledge: understandings, memories, experiences, beliefs. Someone who has experienced extreme trauma can exhibit different personality traits than someone who has not.

You'll notice most schemas discussed above (and indeed, most personality types as widely considered) are fixated on only Motivations, and certainly it's possible that in a personality generation engine, that is a sensible place to start. At least in the West, it seems our society is more comfortable describing differing internal drivers as primary identity markers than ascribing our personalities as the result of circumstance, capability, relationships, or beliefs. Intere stingly, as the Civilization series has iterated, we have seen each of these four aspects become increasingly transparent to the player, even as they become increasingly complex.

I'm still developing a theory of how a generated personality could dynamically balance expressing "deeper" needs (safety, hunger, loneliness, self-esteem) with pursuing goals (ambition, friendship, self-improvement, marriage), using motivations, relationships, abilities, and knowledge as factors for behaviour... and ideally, be open to player interpretation through show-don't-tell methods.

However, this is all skirting dangerously close to procedural storytelling, so I welcome any and all input! Comment below at your leisure, or ping me on Twitter for a more conversational tone. Happy generating!

This article was later followed-up with Maximizing the Impact of Procedural Personalities.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like