Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

At GDC, game designer Richard Rouse III outlined six different techniques for adding dynamism to game stories, and cited several games that exemplify each of these techniques.

"Game streaming has revealed a dirty little secret," says Richard Rouse III in his Tuesday GDC talk "Dynamic Stories for Dynamic Games." Youtube viewers who watch multiple Let's Plays of a given game can now see just how often players can make very different choices and wind up with a similar result. The possibility space of games often isn't as wide as it appears to be.

"We've made gameplay experiences feel dynamic, but then the outcome is exactly what we wanted to happen," says Rouse. "We can’t hide behind that anymore."

Rouse insists that a writers must fight for the time and resources needed to create a genuinely dynamic story, and insists that this gives games a real commercial advantage. He points out that players clearly respond to the vast openness of AAA game worlds in Fallout and GTA and Witcher games, and they also love the unique possibilites that expert use of randomness and procedural generation can add to indie titles like Don't Starve, Spelunky and Darkest Dungeon.

"Players have a limited amount of money," he says. "They want to get value out of games, and one way to give that value is to make them feel that the game is really reacting to what they’re doing."

Rouse outlined six different techniques for adding dynamism to game stories, and cited several games that exemplify each of these techniques.

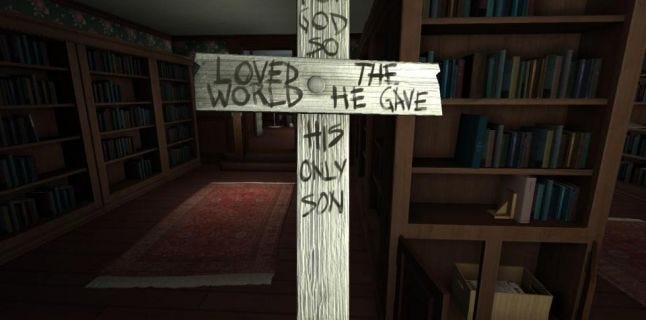

Even relatively straightforward games can have side narratives and deeper story threads for more dedicated players to tease out. Consider the crucifix or the combination to the safe in Gone Home.

Rouse also points to Jordan Mechner's underappreciated classic Last Express, in which certain conversations and events are so time specific that it's impossible to get to them all in one playthrough.

A story that leaves a lot up to the player's imagination can make a game feel more dynamic. You can see this in elliptical works like Dear Esther, as well as in games like Silent Hill that give players tiny slices of a densely detailed story.

Rouse points out that this isn't a game-specific technique. Part of why books like Slaughterhouse Five and The Martian Chronicles pull readers in is because they are deliberately convoluted, and leave a lot out. And part of why movies like the Shining and Inception have such cultish followings is because they leave a lot up to personal interpretation. (Though Rouse points out that both of those movies balance their open endedness with a closing moment that adds some sort of resolution.)

Game writers have to present players with an openness that invites them to fill in the cracks with their imagination, while avoiding obtuseness that leaves them confused or hurts engagement. Rouse quotes Sony Santa Monica senior Designer Brian Upton's book The Aesthetic of Play:

“As we leap from beat to beat, we choose a set of interpretive constraints to explain each beat’s presence. These interpretative constraints generate expectations about the direction and significance of the story. Future beats either confirm or falsify these expectations, triggering either satisfaction or frustration.”

Players appreciate a game that clearly takes note of the decisions they make. Rouse cites Bioshock allowing players to harvest or rescue the Little Sisters, or the increasing number of rats faced by those who play through Dishonored in a dishonorable manner.

He has more praise for Telltale's Walking Dead series, which he says was very good at presenting players with choice points where there was no clear sense of which option was "good" and which was "bad." Firewatch, created be several people who worked on the Walking Dead's first season, strikes him as an interesting evoolution of this, with many small choices effecting things in subtle ways.

Rouse encourages attendees to read Sam Kabo Ashwell's maps of the different patterns of choice in games.

Next, Rouse points to a method of dynamic storytelling that he feels is underutilized in games--dynamically changing not just end results and outcomes, but what leads up to it.

For instance, the movie version of Clue had various endings with various killers, but that meant that none of the clues leading up to these endings would allow viewers to definitively determine whodunnit. What Rouse was describing was a dynamic game story in which dynamic shifts in how the story unfolds would naturally lead players to unique outcomes.

As exemplars, Rouse points to Jon Freeman's classic 1983 mystery game Murder on the Zinderneuf, which randomly generated crimes, suspects, and clues for endless replayability. (The recent Black Closet by Hanako Games also presents players with randomly generated mysteries.) He also points to the point-and-click Blade Runner, in which a die-roll at the beginning of the game determines which characters are replicants.

Another way to make a story feel more alive is with characters who respond authentically to whatever the player does.

The Sims is a game with a very wide possibility space, and the characters behave realistically whether players are trying to pair them off and wed, or are trying to torture them.

Rouse also cites the Civ games, which are not generally thought of as having compelling characters. But he points out that rival rulers in the game have their own motivations, and remember the players past actions. He also points to Alpha Centauri, in which each head of state has their own agenda and beliefs, and they give you feedback based on how you played. "There's no reason that that kind of faction-based reaction couldn't work in narrative games," he says.

Rouse points to Prom Week and Emily Short's IF experiments with Versu as instructive examples. Both feature elaborate AI that creates very interesting and deep characters and relationships.

He observes that a cartoonish slapstick tone can allow for a broad range of reactions, and encourage players to think that any decision they make, no matter how absurd, will fit with the world of the game. He also stresses the importance of telegraphing what's happening in the heads of characters to to players, the way Prom Week does with its detailed menu system.

Rouse pointed attendees to a GDC talk by the Prom Week devs on constructing socially engaging AI, and presented this quote from Emily Short:

“My general rule of thumb is it’s pointless to simulate anything in AI that you don’t also have a plan for communicating to the player – otherwise they don’t see how clever you’re being, or (worse) what is actually sophisticated behavior winds up looking like a bug.”

"This is the flipside of character simulation," says Rouse. "it's letting the story drift in interesting ways, like a really good DM of a tabletop RPG who knows how to give players lots of agency, while steering things back to story."

He cites the interactive drama Facade, in which players stumble upon a couple having a bitter fight that could destroy their relationship. Tellingly, the game has become a hit with streamers despite the fact that it came out in 2005, when Youtube was still in its infancy. "It's found an interesting second life because it's so reactive," says Rouse. Let's Players love to push the boundaries of the game, showing how it can roll with the most outrageous responses they can come up with.

Rouse also cites the Nemesis system in Shadow of Mordor, which layers compelling personal rivalries onto the action. Each victory and defeat, each wound inflicted, helpts to create a tiny mininarrative unique to each player. Michael de Plater, the design director of the game, has said that, "The Nemesis System is emergent procedural narrative that’s neither linear nor branching."

Read more about:

event-gdcYou May Also Like