Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Creative Director Alex Beachum and Producer Sarah Scialli explain the process of taking a USC Masters Thesis project and turning it into one of the most unique games of the year.

Coming a little out of the left-field, Outer Wilds has taken a short while to gain the kind of awareness it deserves, despite having been in development for a couple of years. Beginning as a student project, (Alex Beachum's Masters Thesis at USC), it's now blossomed into a fully fledged release, accruing a large number of development credits, both from the students that worked on it then, and the full-time developers that are working on it now.

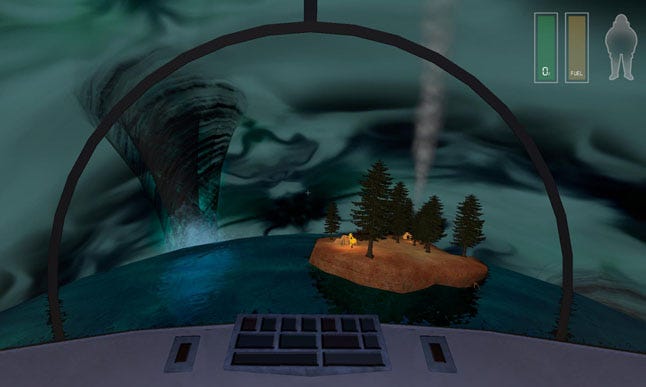

Outer Wilds, nominated for the Excellence in Design award and also the Seumas McNally Grand Prize in this year's IGF Main Competition-- as well as being an honorable mention for the Nuovo and Excellence in Narrative awards -- puts players in the shoes of a time traveler stuck in a loop, with just 20 minutes to investigate a mysterious solar system at the end of the universe.

There's more than a little wiff of Majora's Mask about it, but fundamentally it's a game about exploration and discovery, using that twenty minute loop to create a solar system that's ever-changing, where a planet at minute one is not the same planet in minute fifteen. It encourages constant replaying, delving into knooks and crannies of each world for no other reason than because it's there to explore, and there might be something to marvel at.

As part of our Road to IGF series of interviews with nominees, we talk to Alex Beachum, Outer Wilds' Creative Director, and Sarah Scialli, its Producer, about the production of the game, as well as some of the more unique elements that make it such a compelling place to explore.

What is your background making games?

Alex Beachum (Creative Director): When we started Outer Wilds, most of our team members were students at the University of Southern California, the Laguna College of Art and Design or Atlantic University College.

I think the first game I ever made was the "3D platformer" I built out of Legos when I was twelve. My sister would tilt the Lego joystick or say "boing" (to jump) while I moved her character around the level. I didn't decide to pursue game design as a career until I applied to USC's Interactive Media graduate program, where I began Outer Wilds as my Masters Thesis.

What development tools did you use?

Beachum: The game itself was built in Unity3D, where the physics engine has been a really good sport about not imploding from all the ridiculous things we ask it to do.

Early on we used paper prototypes and even a tabletop roleplaying session to experiment with different approaches to narrative design. More recently we recreated the entire game as a 2D text adventure using a java library called Processing, which lets us test the entire narrative structure much faster than we could in the game proper.

How long have you been working on the game?

Sarah Scialli (Producer): The game formally began in Fall of 2012 as a USC Masters Thesis as well as a USC Advanced Game Project for the 2012/2013 school year. Post graduation, the project has moved steadily along, and we look forward to completing a commercial release of the game.

How did you come up with the concept?

Beachum: Outer Wilds coalesced over a long period of time from a bunch of nebulous ideas and prototypes. Initially I had just two (admittedly vague) goals in mind.

The first was to capture the spirit of space exploration ((in the tradition of Apollo 13 and 2001: A Space Odyssey) by having players navigate a world driven by forces beyond their control. This lead to the idea of a solar system that dramatically changes over a short-but--replayable period of time.

The second goal was to create an open-world experience where the sole purpose of exploration is to answer questions about the world you're in. In particular I wanted to avoid giving players explicit objectives without making the game feel aimless.

These two goals spawned a smorgasbord of seemingly-unrelated prototypes involving model rockets, camera-wielding probes, quantum, forests, and miniature solar systems. I was having a hard time pulling them all together until one of our colleagues had the brilliant suggestion of making an "emotional prototype" to explore the game's mood. The resulting prototype, which invited players to roast a marshmallow as they watched the sun explode, established the tone of the entire project.

Once the game had a soul, the remaining pieces started to fall into place. The "camping in space" aesthetic was inspired by my love of backpacking, and the time loop was invented to make repeated playthroughs diegetic. Our approach to narrative design was actually informed by the Wind Waker, whose characters incite player curiosity by telling stories of distant places (most notable Lenzo the photographer). We simple expanded the concept to create a world that constantly makes references to things players can actually go out and discover.

It's difficult not to see the thematic similarity between Outer Wilds and Majora's Mask. Is the former inspired by the latter?

Beachum: Majora's Mask is a favorite among our team, so we'd be lying if we said it didn't have a big influence on the game. The sense of impending doom (in particular the music that plays during the final two minutes) was very much inspired by Termina's lunar predicament.

Despite their obvious similarities, I do think the two games use time loops in very different ways. Majora's Mask creates this complex schedule of events that lets you play around with causality, whereas Outer Wilds' time loop primarily exists to allow the creation of large-scale dynamic systems. Certain irreversible processes like the destruction of Brittle Hollow just wouldn't make sense if we never reset the clock. Plus it turns out you can get away with some pretty crazy things when your simulation only has to be stable for twenty minutes.

Scialli: We love the idea that the time loop enables exploration to be as much about 'when' players explore as about 'where'. We use the time loop to allow players to explore the same areas differently throughout a single playthrough, and then use what they've learned in earlier playthroughs to affect how they explore in subsequent loops.

When Outer Wilds is so much about exploration and discover, what is behind the choice to give the player a health bar and an oxygen tank?

Beachum: I'm fascinated by the fact that humans strap themselves to giant rockets just to explore an environment (i.e. space)) where they clearly aren't supposed to be. That sense of fragility is a major theme in Outer Wilds. The health meter and oxygen tank are constant reminders that you're far from home, out of your element, and if the smallest thing goes wrong, you're toast. They also establish your ship, which is far more durable and replenishes your oxygen, as a safe house in an unforgiving cosmos. When you're forced to leave your ship to explore a planet, it creates this gradual tension as you venture farther and farther away.

I also think a certain amount of mortal peril keeps exploration from feeling too passive. the decision to investigate the cave is a lot more interesting if you're worried about what you might find inside. For a game without any combat, we've implemented an awful lot of different ways to die.

Outer Wilds has a surprisingly large development team compared to most indie studios. Is it difficult to coordinate this many people?

Scialli: The game team was really only that large during the 2012/2013 school year. Each member of the team brought a unique voice to the project, and we are happy that we had a chance to collaborate with them.

The difference between coordinating a team of students and a full-time team is largely that many of the students were working outside of their coursework purely out of their passion for the game. It is a huge benefit to have so many people who care so deeply about the project, but we also had to understand that if something came up for a student outside of the project, we'd have to adjust.

Have you played any of the other IGF finalists? Any games you've particularly enjoyed?

Beachum: I'm usually not big into strategy games, but I've been really digging Invisible Inc. 80 Days is also wonderful - I'm honestly floored to be on a list with all of these folks. Oh, and I love that How do you do it? got a Nouvo nomination. It looks so charming and innocent but I think it says some really important things.

Scialli: I'm really impressed when a game team takes a simple concept or theme and runs as far as they can with it. So I especially enjoy how the FRAMED team ran with their graphic-novel-esque rearranging mechanic, and used it to infuse their narrative and visual design. I also am a historical fiction fan, so I thoroughly enjoy diving into the rich world of 80 Days. As Alex said, we are incredibly honored to be listed among such amazing games.

You May Also Like