Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

If there's one advantage that games have over other mediums, it's their ability to have the participant not just witness someone else's doings—but to put them in the middle of said doings.

If there's one advantage that games have over other mediums, it's their ability to have the participant not just witness someone else's doings—but to put them in the middle of said doings. Of all the genres that promise an adventure that lets players realize their fantasies in sundry ways, role-playing games (RPGs) stand head and shoulders above the competition.

Since the dawn of computer RPGs in the 70s, the genre gradually offered new ways for one to craft and unleash fictional versions of themselves or of characters living in their heads.

Yet such a feeling of creative experimentation is more than just one concerned with quenching players' thirst for escapism. It's also focused on testing the player's morality, problem-solving chops, curiosity, and willingness to take risks in a setting other than real life. And if developers get it right, the title's acknowledgment of the player's unique in-game role will encourage them to keep playing and see the consequences of their actions.

The ability to create your own party and tweak countless skills in Icewind Dale II (2002); the realm-building that can shape the world and kinds of encounters you tackle in Pathfinder: Wrath of the Righteous (2021)... RPGs bear many parameters and paths for players to adjust and take respectively on their mission to shape events, people, and locations using the mechanics and systems that the game features.

Over time, other genres looked to RPGs and borrowed some of their loot and character development aspects for their own purposes (e.g. 2009's Borderlands and 2018's Call of Cthulhu). But despite such cross-genre efforts, RPGs remained fresh in folks' eyes.

There's a reason for that: whereas most genres see the avatar merely trek about the world and overcome challenges, RPGs concern themselves with making players feel like they're a part of the world they inhabit. And not (just) because the game boasts realistic visuals and audio. Instead, RPGs achieve an unparalleled level of immersion by doubling down on the player's ability to assume and play one of many roles in a multifaceted world.

Hence the importance of the "RP" side of the equation. And there are many ways that the game can provide freedom and heft to the role player's deeds.

----------------

Offer tasks with multiple paths and long-lasting consequences

Player choice is par for the course when it comes to RPGs. If a genre entry's goal is to make you feel like a part of the world—a part that can shape others via their actions—then having the game recognize one's playstyle and the possibility for it to leave its mark anywhere makes total sense. That said, the choices presented in-game mustn't feel trivial or random: they must also entail long-standing consequences reflected in the environment and/or NPCs.

A simple example is choosing whether to deal peacefully or violently with raiders threatening to raze a village of pacifists to the ground. De-escalation may mean having to learn and use silvery words, but it does translate to a better reputation among the villagers and even the raiders if they buy into your persuasive tactics. On the other hand, repelling the raiders violently may mean a swifter outcome, but it can also lead to further retaliation from other bandits. Not to mention a drop in likability among the villagers.

If there's one game that epitomizes the gravity of choice and consequence, it would be Alpha Protocol (2010). While decisions you make for your character build do impact how you play, the real moments of truth lie in how you converse with NPCs and approach situations. Not to mention the order in which you tackle missions across the title's many locations.

From bypassing a suspicious guard with forceful words to taunting a potential ally by mocking the death of his right-hand woman, Obsidian Entertainment's espionage RPG never misses an opportunity to remind players of the consequences of seemingly minor actions. If they are not felt immediately, they most certainly will later in the game—with missions starting and playing out differently depending on past endeavors.

It's a testament to the developers' trust in player choice that Alpha Protocol can unfold and end in ways both predictable and unexpected. This not only personalizes the experience, but also makes it highly replayable—with players being able to channel their inner James Bond, Jason Bourne, Jack Bauer, or a blend of the three JBs throughout their playthrough(s).

Honorable Mention: The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt (2015). The quests involving the Bloody Baron, in particular, highlight the importance of carefully pondering one's narrative-morphing decisions—lest they engender unforeseen deaths and heartbreaks. That the quests themselves reinforce the theme of finding a lost loved one adds further heft to the proceedings.

Feature systems that allow players to interact with a world's social and economic facets

Of course, there's more to choice than the moral sort—with role players also desiring to have a say in how they choose to interact with their surroundings and their inner workings. This is an aspect of RPGs that separates them from other genres, with environments being more than just eye candy full of obstacles to negotiate. To be more specific, an RPG can go the extra mile with its portrayal of societal goings-on by including systems and amenities that one can leverage and even influence if they wish to invest time—and money—into them.

A clear example involves the chance to own property and collect rent/income from it. A player who wishes to take on the role of a business/land owner is free to adjust the price of goods and rents depending on their moral alignment and/or how badly they need the money. On top of adding another layer of interactivity to in-game amenities and services, the idea of virtual property ownership enables players to forge a connection with their bearings that goes a lot deeper than merely revisiting the same settlement just to resupply and get back to crawling and looting dungeons. Might as well make your fortune in a safe town!

If this concept sounds familiar, that's because it's realized in Fable II (2008).

But there's more to it, for the amount of income generated by player-owned businesses also depends on the quality of the business, the economic level of the town, and the shopkeeper's opinion of the player. Therefore, property ownership is hardly a static and passive endeavor—further compelling players to double down on their role as business/land owners by periodically checking the status of their property.

This is to say nothing of the other features that embed the role player into the socioeconomic fabric of Albion. The ability to woo, marry, and divorce loved ones; the opportunity to do jobs (e.g. blacksmith, woodcutter, merchant, etc.) and earn quick gold; the chance to raise children and spend time with them...

Suffice it to say that Fable II caters to those who like to play the role of adventurers who don't mind settling down and being as close to their community as they are to their canine companion.

The result? A system-rich world that invites players to think beyond the traditional gameplay loop of combat, exploration, and dialog.

Honorable Mention: The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall (1996). The title's debt management and court systems are especially noteworthy since they add complexity to the use of gold and how the authorities deal with ruffians. It also helps that the game tests the player's Etiquette and Streetwise skills when trying to convince judges that the charges against them are dubious.

Provide ideologies that one ponders and deeply engages with

It's not material features that players can tap into in their role-playing spree, however. How they think about the world they inhabit and subsequently interact with it can be equally effective in having the world leaves its mark upon players—and vice versa. This generally comes in the form of ideologies and lines of thinking shared among the game's NPCs, who then proceed to reinforce their worldview by either isolating themselves from the outside world or by actively clashing with those they constantly other.

This spiritual touch isn't just there to imbue the world with a palpable feeling of verisimilitude (i.e. societies never bear just one point of view). It's also there to take the player's fantasy to the next level. A deeper level, to be precise, that sends them tumbling into uncharted territory that may bear some ugly truths about the universe they're in. But as mentioned before, RPGs can test a player's morality and willingness to take risks by sizing up ideologies that they'd have second thoughts about studying in the real world.

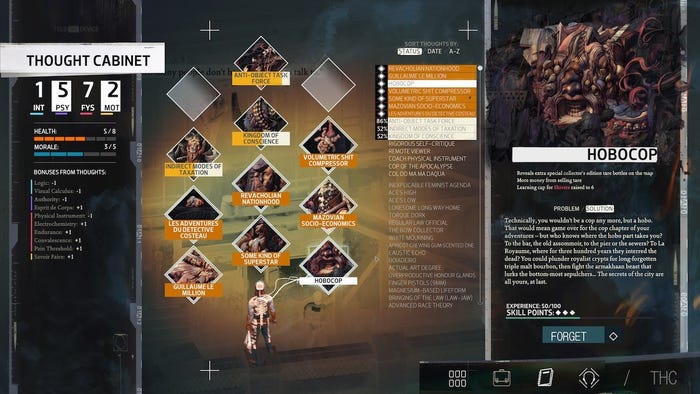

This is an area in which Disco Elysium (2019) truly shines. In this cop-themed RPG, players will be exposed to different ideologies such as communism, fascism, moralism, and ultraliberalism. In one particular instance, the avatar will be compelled to ponder a highly questionable ideology so as to get past a dauntingly tattooed NPC guarding a critical path. And depending on the political alignment one was leaning toward, a quest unique to said alignment will eventually become available to players who took the time to mull over Revachol's eclectic web of partisanship.

All of this is on top of the Thought Cabinet that allows players to internalize many lines of thinking that not only offer stat benefits (and penalties), but also insight into the avatar's past life and understanding of the world he lives in. Narrative and mechanics thus fuse into a gameplay loop that players can enable via their curiosity about the world's sociopolitical climate.

Therefore, Disco Elysium grants players the chance to shape and use their brains to navigate the world however they see fit—a wise move on ZA/UM's part given the novelty of malleable thoughts as gameplay tools. Especially when compared to most RPGs' emphasis on armor and weapons.

Honorable Mention: The Age of Decadence(2015). From the highly religious House Crassus to the materialistic Commercium, the title's factions vie not only for control, but also for the player's attention and loyalty to their cause. It's up to players to decide which ideology closely aligns with their interest, which also depends upon the background they pick at the start of their adventure as well as the reputation they forge on their journey.

Reward players for engaging with the world in various ways

When one thinks of leveling up, chances are they think of combat and quest completion as the chief (and sometimes sole) ways to strengthen a character via the accumulation of XP. While it's reasonable to assume that one can get stronger through might and task management, RPGs are capable of expanding conditions for rewarding the player's engagement with the world's NPCs and locales. Especially when compared to other genres that feature RPG elements (e.g. shoot down enemies for XP in Call of Duty games) and don't accommodate less combative and more story-focused role players.

For example, let's say that we have two kinds of players: one who's a bookworm and the other an observer of all things urban. The game may reward the former's curiosity by filling the world with books and documents about its history and politics, the act of reading granting XP for every absorbed bit of new insight. Likewise, the urban observer may be spoiled for choice when they notice lots of vantage points from which they can study city life and spot fetching details (e.g. people whose swift walking speed betrays their being office workers looking to make a quick buck). In other words, the RPG should acknowledge the kind of endeavor that players in specific roles would tackle and reward them for being true to their character.

Torment: Tides of Numenera (2017) serves as an example of how developers can think outside the box when it comes to granting XP. As a narrative-driven RPG, Torment: Tides of Numenera focuses less on combat and more on dialog and exploration. Therefore, interactions with NPCs, objects, and even the avatar's memories via the Anamnesis skill provide an avenue for earning XP and valuable objects from time to time.

For instance, players who like to learn about the NPCs' lives are welcome to inquire about a couple's adoptive son and even have a word with the boy himself. By selecting the appropriate topics, XP's granted to the inquisitive player. Additionally, players who like to play detective can earn XP from closely investigating a crime scene in Sagus Cliffs' Underbelly.

By recognizing the fact that curiosity comes in many forms outside of fights and quests, the developers built an RPG that responds to players at almost every turn via far-out sights and worldbuilding—inviting one to engage with them. Discovery itself can be its own reward, but the awarding of XP and items can serve as further motivation for players to stay true to their knowledge-seeking roles and use the information they gather so as to better navigate their circumstances and surroundings.

Honorable Mention: Yakuza: Like a Dragon (2020). Side activities such as the batting cage, golf, and even watching a movie with a fellow party member can yield stat and relationship boosts outside of combat. Not only do they encourage players to go off the beaten path, but they also reinforce the wacky but fleshed-out nature of the title's rendition of urban Japanese life.

Don't make one feel guilty for favoring one moral side over others

It's one thing to provide a wealth of options for the budding role player to experiment with as they wend their way through the world. It's a different kettle of fish, however, for said world to allow said role player to go wherever they please on the morality spectrum without admonishing them for taking things a bit far. This can range from sending evil guns-for-hire after you to portraying a world in which folks are so firmly lawful and good that players feel guilty about doing devilish things. Especially if it means losing access to quests and locations where one may unwind and resupply.

While it's true that reputation-based content shouldn't be universally available to players who favor one moral path over others, it's also true that an RPG should ideally be designed in a way that makes all moral paths viable options that provide different but equally proportioned sets of benefits and penalties. One way of achieving this is by making the world itself baleful enough for evil players to still seem normal compared to malicious NPCs, yet lenient enough for good players to act virtuously wherever appropriate.

Case in point? Tyranny (2016). Whereas most RPGs cast players as rising heroes tasked with ridding the world of evildoers, Tyranny puts them in the shoes of a soul serving an authoritarian regime and responsible for sizing up the land said regime lords over. From the get-go, the game world's mood makes it clear that evil playthroughs make sense within the title's context—but that's not to say that relatively virtuous acts are out of the question.

One notable example concerns the burning of a magical library full of people. If players are evil, they can set it ablaze without telling those inside to clear out. Yes, it's a heartless act, but your occupation and the state of the world mean that folks around you will take that kind of behavior for granted.

But should players have a heart, they may give those same people in the library advance notice prior to the fiery act. While the avatar remains a tool of the tyrannical powers that be, they will receive compliments from the people they've spared later in the game. Tyranny may be a game about strengthening an evil power's iron fist, but it's one that doesn't shackle players to a wholly dark path. The result is a tonally unique experience that analyzes human nature and morality via choices that highlight the potential for compassion and mercy in a world that seems utterly bereft of them.

Honorable Mention: Dragon Age: Origins (2009). Between the Darkspawn laying waste to the land and the sociopolitical tensions making monsters of folks, the game's harrowing atmosphere means that evil players are free to go wicked without sticking out like a sore thumb among the populace. This is to say nothing of how morally ambiguous things can get.

Make encounters conducive to all available playstyles

As mentioned before, RPGs distinguish themselves from other genres through their willingness to let players tackle situations in a way that befits the role they take on and play. In a lot of cases, that design philosophy manifests itself in encounters with NPCs outside of and during combat—which ideally factor in all the available playstyles and outcomes that stem from players being true to their gameplay preferences and moral values.

A combat-centric example would involve stealing a precious item held inside a bandit hideout. Do players hack and slash their way through, or do they try sneaking their way in and out without laying a finger on their enemies? Another scenario could see players enter a bar and witness a surly patron threatening the bartender. Do they defuse the situation by bribing the patron into walking away, or do they put a bullet between the patron's eyes? In any case, players should get the feeling that all options are on the table—allowing them to personalize their playthrough with any mix of said options.

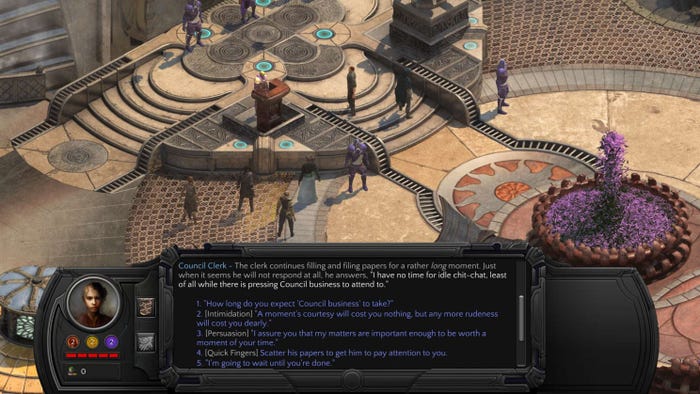

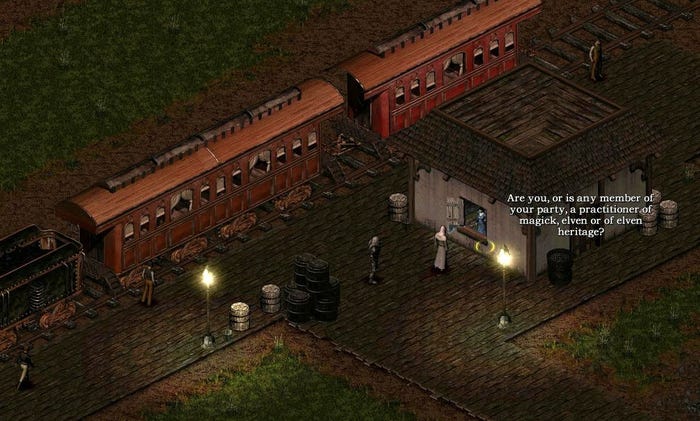

Enter Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura (2001). As implied by the extensive character customization features (race, gender, background, etc.), the game focuses heavily on giving players a chance to bypass obstacles and complete quests in ways that can only arise from very specific decisions made while crafting their character and exploring the world.

For instance, playing as a female character may imply that you're not able to enter the Wellington Gentlemen's Club while doing a quest. But should you be willing to spill some blood or pick some pockets, one can feasibly rob a member of the required paperwork for admission into the Gentlemen's Club.

Likewise, one may go about robbing a bank for a quest giver in sundry ways. They can a) pick the vault door's lock, b) break the door down, c) steal the key from the Bank-keeper, or d) kill the Bank-keeper before grabbing the key. And in case they want to keep the spoils for themselves and bypass the quest giver, they can a) steal the safe combination from him, or b) report him to the authorities after getting the combination from the quest giver.

Ergo, Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura rewards those who observe their surroundings and circumstances before taking idiosyncratic action. Such is the joy of making discoveries by being true to one's role.

Honorable Mention: Baldur's Gate 3(2023). Thanks to Dungeons & Dragons' 5th Edition ruleset, combat emphasizes improvisation and experimentation with different builds. You can even play the role of a chronic boot thrower, dealing damage with footwear. It also helps that the environment can be turned into a weapon (e.g. light surfaces on fire, turn a surface into ice, put out fires, collapse structures, etc.).

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like