Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

I've come up with a theory, which also explains why many have such a hard time putting a game like Super Mario Brothers at the top of their list of great video game stories. My theory is that this bias against simple stories exists for two main reasons.

When I ask people to give me examples of great stories in any medium a rare few suggest kid, simple, personal, or short stories like those found in some commercials. I find this odd. So, I've come up with a theory, which also explains why many have such a hard time putting a game like Super Mario Brothers at the top of their list of great video game stories when it ranks high for its gameplay. My theory is that this bias against simple stories exists for two main reasons.

The first reason is that as we grew up, there were pressures from various areas to "upgrade." It's the old "putting away childish things" idea that people unconsciously apply to various areas of their lives including entertainment. I vividly remember my middle and high school days when my peers openly rejected cartoons because they claimed they were too old. Or my high school and college days when many thought they out grew video gaming. Apparently, an easy way to measure the maturity and quality of a story was based on its complexity. And everything simple was for kids, less intelligent, or less mature people.

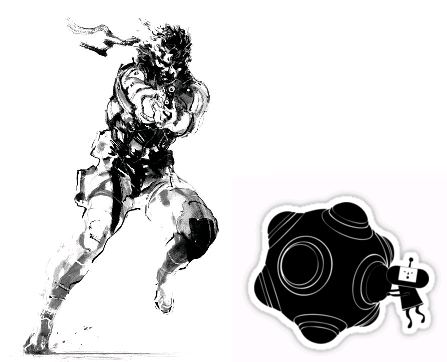

Complex Metal Gear vs Simple Katamari

The second reason why people generally consider more complex stories to be superior to relatively simple stories is because of an intuitive understanding of emergence. This is not the emergence of gameplay, but of numerous comparisons. Think about it this way. With few complexities in a story, there's little room to elaborate or derail the execution. Setting, characters, plot, and theme are more likely to be straight forward making for fewer "ah-ha" moments that come when you piece together "hidden" details. For example, take this story: One day a man woke early up, went to work, and fell asleep. You see? Not much to it.

The more complex the story (more details) the more individual details there are to cross compare, obscure, and elaborate with. Every detail added can do increasingly more to a work depending on how it supports and deconstructs the other details. This is why it's inherently difficult to develop the execution facets of efficiency, coherence, and pacing in complex stories. There's just more story stuff there for the creator to keep track of and present clearly. So, it's no wonder that we tend to assume that complex stories are great. It takes a lot of work to sort out all the details of a complex story. And if a complex story confuses us, perhaps because it's poorly crafted, we tend to fault ourselves. Perhaps we missed or overlooked a detail. Perhaps we just need to think about the work longer. For these reasons, we tend to give complex stories greater leeway.

With that said, I've seen more complex stories falter and fail than simple stories. However, many, if not most, of my favorite stories are complex. Here's the deal. In the same way that emergent gameplay possibilities explode at a rate that's exponential and beyond, so too does the number of comparisons increase with increasingly complex stories. The more complex a story, the more one must re-experience, study, and reflect on the content to understand how the story builds up into a stronger work or falls apart. There's no way around this requirement. You can get faster at such analysis and critical thinking, but the work load remains the same. So, if you're the kind of person who doesn't typically do the required work to understand complex stories you should consider if you're only getting as much meaning out of the story as you would from a considerably less complex work. What's the point of preferring deep and complex stories if you're never going to dive deeply into them? If you're going to stay on the shore and never get your feet wet, you should at least appreciate simple stories as much as complex stories.

Complex Killer 7 vs Simple Shadow of the Colossus

When I think about all of my favorite games, stories, people, movies, plays, TV shows, etc., I realize that I've put the work into each. Whether it's thinking time, debates, cross comparisons, or just experiencing it multiple times, I tend to like anything better when I put in the work to understand as much of it as possible. The more work I put into it and the more it holds up under my critical analysis, the more entertainment I derive. The best part is, the entertainment value outweighs the work requirement.

With all of this focus on complex stories, I should say that it's not uncommon for the stories most would consider simple to have depth, elegance, and a high level of craft. The common idea is that simple stories are inferior to complex stories because they have less intellectual potential. People feel that they "get" simple stories after just experiencing them once. The truth is simple stories can have much to uncover like complex stories.

To prove that the seemingly simple can extend deeper than you know, I present my poem "Starfish" and my analysis. The following is an excerpt of a paper I wrote for my creative writing fiction course last year. The thesis explores how characters with complex psychologies are presented (execution) across various mediums.

-----------

Poetry is where I’ll start. Because poems tend to be very short, they are also likely to characterize in highly concentrated, abstract ways that require the reader to examine the text very closely. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for the main character of a poem to simply be the speaker with the content of the poem directly reflecting the speaker’s point of view. This method of characterization is analogous to how fiction writing uses description of setting to convey the point of view of a character. All of these ideas are best explained with an example.

Starfish

I learned about stars in Elementary

Books, and planets, and orbits,

But mostly far away things. My

Teacher used to point down into

The pages, finding the points and connecting

Them from the hundreds of stars on the page

With her fingers. I could never find

The shapes and figures at the end

of my brown fingertips. I searched anyway.

I remember pointing at the fish off the bridge

At the zoo, and turning my

Mother’s purse inside out for a quarter.

I turned a knob and out came a handful of feed.

Then I threw the whole fist in at once

Hundreds of little brownesses racing

To reach the surface of the water,

to touch the frenzied fish,

because my little arms couldn’t

Reach the waves.

But you, you’re a starfish.

You’re a star. And a fish.

Five points. Five Fingers.

You get to touch everything

Because you don’t have any eyes.

I guess that’s the point.

~Richard Hakem Terrell

In this poem understanding the speaker is everything. There’s no dialog in the poem, so everything about this speaker must be conveyed via descriptions and actions. Yet, the speaker makes very little description of himself outside of two references to his “brown fingertips” and “little arms.” The evolution of the speaker is organized in 3 distinct memories or scenes in time. Though we’re not exactly told that the first two stanzas are arranged in chronological order, we know by the tense shift (or lack of past tense verbs in the first line of the stanza) that the final stanza is closer to the present.

The opening line of the poem suggests that learning and understanding is the central conflict for the speaker. This leap may seem unintuitive, but the reader should key into this topic by using the title as a sort of decoder. In other words, the poem is titled “Starfish” so naturally the subjects “star” and “fish” should be addressed with extra attention. Learning about “far away things” is another way of expressing that the speaker’s conflict involves understanding the world around him. It’s obvious by the actions of the speaker in the first stanza that the method of hands on investigation doesn’t work when learning about stars. In this way, the stanza describes a young boy on the verge of learning that his somewhat infantile method of learning (hands on, tactile, to the mouth) is obsolete in his growing world. The first stanza ends with the actions of imitation, visual searching, touching, and a resolution to keep looking for the lesson to “click” for him. The stage is set for the speaker.

In the second stanza the themes of touch and understanding are extended, but this time with fish. Like the resolve in searching “anyway” in the first stanza, we find that the speaker is active in searching through the purse, turning the knob of a fish food vending machine, and throwing the food to the fish all at once. This time there’s no figure that the speaker immitates. Therefore, we can assume that it is his own idea to interact with the fish by feeding them. This inventiveness illustrates that the speaker might be older or at least more independent than he was in the first paragraph. Being aware that his “little arms” couldn’t reach the surface of the water is just one more level of self-awareness that outlines the speaker's growth.

Finally, in the 3rd stanza the speaker addresses a starfish directly, perhaps at some kind of hands-on exhibit at an aquarium. After some time has passed, this is the situation in which the speaker can experience a “star” and a “fish” directly. And in a precocious moment, the speaker tries to relate to the starfish directly in front of him by drawing on his past experiences and his awareness of himself. He realizes that a creature like a starfish gets to have hands on experience with everything it can perceive, which means that it probably doesn’t experience what it’s like not to understand something intuitively. In other words, the starfish doesn't understand that there even are “far away things.” The ending, “I guess that’s the point” is a small turn in the speakers attitude/perspective that lets us see the trajectory of his intellectual growth.

So the evolution of the speaker is developed line by line by the fusion of actions and themes. We understand the psychology of the speaker and get to share in the exact moments that makes up the logic he uses to make that unintuitive leap into the darkness that is adolescence. The leap, or conclusion, is somewhat awkward and incomplete. The speaker is still a kid and just much to learn.

I find that when characters are shown in action that we can understand their psychologies and how they evolve much more intuitively and effectively than if the characterization is conveyed mostly with statements on their feelings and thoughts. Furthermore, simple details of a character’s backstory can easily distract from the momentum/immediacy of a story by inundating the reader with a list of facts that don’t directly relate to any present action/conflict/time. It’s not compelling for a character to say “I’m crazy.” Instead, by talking beside or around the point, character can come to life for the reader.

In part 6 we look at the narrative of pure gameplay and how game design might improve to present a clearer story to its players.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like