Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Make no mistake; stories can be presented entirely through gameplay. In this article, we'll take a closer look not at "narrative/story games" but the story of gameplay and consider why we separated the two in the first place.

Make no mistake; stories can be presented entirely through gameplay. This includes single player games like Super Mario Brothers or Shadow of the Colossus and multiplayer matches. If this statement seems strange to you remember that a story is nothing more than a series of events featuring characters in time and place. In this article, we'll take a closer look not at "narrative/story games" but the story of gameplay and consider why we separated the two in the first place.

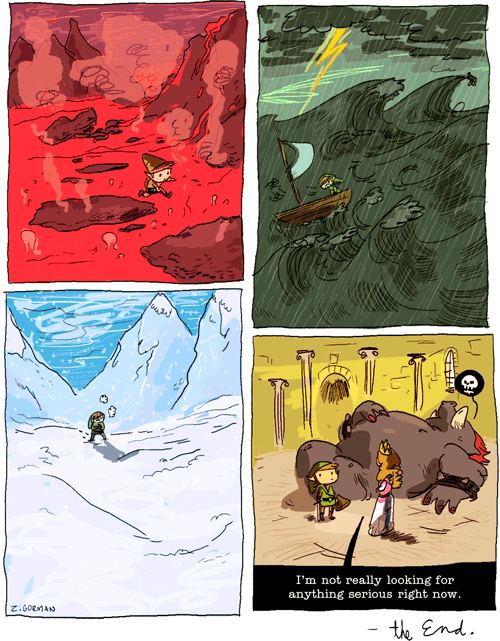

gameplay is also story (image by Zac Gorman)

Throughout this article series I've explained that a game like Super Mario Brothers should be on anyone's list of great game stories if they also put the game on their list of great gameplay. I didn't say this to give SMB more accolades. I made this statement because the very act of playing through the game creates a very personal story. With the player at the helm everything is shaped by his or her actions. In the same way that the gameplay is emergent allowing players to speed up, slow down, grab coins, collect powerups, skip enemies, and bypass entire worlds, so too is the story.

By sharing control of Mario, or any other character, the gameplay story is infused with you as a half-real actor. This means your skills, idiosyncrasies, quirks, and tendencies can be a factor in the gameplay experience and therefore the story. Some characters are more flexible than others in terms of the range of actions and interactions with the game world. Daniel Primed has outline some useful terms for understanding various types of such characterization (read more here).

Co-author : [acting] based on the player’s understanding of the avatar’s principles combined with their own.

Avatar : [acting] based on the player’s understanding of the avatar’s principles, independent of their own.

Viewer : [acting] based on the player’s compulsion.

Director : [acting] based on the player’s ethical [or coherent] interpretation.

We all know that the player is greatly reflected in his/her gameplay actions from personal experience. If this wasn't the case, multiplayer gaming wouldn't be so varied and interesting. When we play against each other we battle the other player not the other avatar/game challenge. Ideas along these lines are nothing new to the Critical-Gaming blog. Back in 2008 I wrote this article about how "I" (the player) is a very important character in gameplay driven video game experiences. In 2010 I wrote about thegame/mental state explaining that the mental goingson of the player are reflected accurately through gameplay actions.

So, why do so many gamers overlook the value and impact of gameplay/player driven video game stories? Perhaps for the same reason why people, in general, do not understand the value in the story of their own personal lives. In high school I made up a quote that encapsulates a personal belief of mine; "everyone has an amazing story to tell. And if it's not amazing, then they didn't tell it right." In other words, everyone's life features sufficient content for an amazing story. And if you don't think it's amazing, then the issue lies not in the content but in the execution (which can be fixed more easily than content).

The problem is crafting a quality story generally requires a sharp understanding of what to cut and what to focus on to produce coherence and the most resonance. I've done this kind of personal-narrative-pruning all of my life. It's no wonder I ended up with a degree in creative writing. Therefore, the solution to the problem of players and people devaluing their own stories requires creating the tools to help people tell and experience their own stories.

Let's look at how the NBA does it (Let's go Mavs! World Champions!). If you compare a professional basketball game to a professional Halo: Reach deathmatch you'll find a lot of similarities. For the purposes of this analysis, I want to focus on the fact that both are activities of pure gameplay. If you are unfamiliar with the rules of either game, you will not find watching the games very enjoyable. To such viewers, some players will just seem to move out of the way for no reason or get whistled by the referee for nothing. You might wonder why one team is doing better than the other or why the players simply don't dunk the ball every play. I'd expect a similar level of confusion for spectators unfamiliar with Halo. If you don't know the rules you cannot understand the strategies at play. If you don't understand the strategies, you can't understand what's going through each player's mind as they evaluate one risky play versus another. But just knowing all the rules doesn't tell you the whole story.

Because Basketball is a real-time game played with two teams of 5 players, there is more motion and action than any one person can pay attention to. The game alone needs 3 referees on the court to have enough surveillance to effectively call fouls. So, how do we, the viewers, keep up? Well, there are a slue of techniques and features that help put the grand story into focus.

Replay/Slow-mo: We're bound to miss part of the action. With camera technology we can re-view and review plays. By slowing down the footage, we can see more.

Commentary: Good commentators express their feelings, predict plays, outline strategies, and explain rules contextually as the game is played.

Analysts: Before and after the game sources from all around give their breakdown on what happened, what needs to happen, and what might happen.

Timeouts: Some timeouts are called by the coaches. There are a few that are scheduled into the games to make time for commercials. Either way, this time is important for giving commentators, coaches, players, and the viewer a break. In this break new plays are drawn, commentators try to catch the audience up to speed, and the viewer is free to talk or walk about.

All the mutliplayer games I know of do a very poor job conveying the story of gameplay. At the start of a match, there's no analysis or commentary. After the match starts, you might get a little smack talk or some callouts but little else. And when it's all over, you might look over your stats and you might remember most of the events vividly, but this is not a story. And until you put the pieces together into a story, there will be a distinct gap in your understanding of what happened. After all, how else can you learn a story if not through story telling?

The more players and perspectives, the larger the field, and the more action packed a multiplayer experience the more complex the emergent gameplay story becomes. A Team Halo Reach match has 8 players/character to keep track of. For an example watch this pro video with commentary. Notice how it's easy to understand what one player is doing, but not what's happening to all 8 players and the match as a whole. StarCraft 2 can have more than 400 units all acting independently on a large scrolling map. Even with a fighter like Smash Brawl team battles where all 4 characters are on the screen at the same time, it's extremely hard to focus on the action let alone keep up with the speed in real time. The bottom line is gameplay can be highly complex thus making the task of telling gameplay stories difficult.

It would certainly take a generational leap of multiplayer design to create a system that can weave the story of our gameplay and tell us in the middle of the gameplay. I've been developing parts of these innovations for years. Though I don't have a working model for these concepts, it's clear that the following features would be necessary in some combination.

Flexible time: Whether games use timeouts, bullet time, turn-based elements, or a dynamic-flexible time system like async more is needed to give players a chance to reflect and focus on additional elements. With real-time gamplay there isn't enough time to commentate, recap, or explain anything.

Record and Replay: Because visual storytelling is so intuitive and effective (and because video games naturally use visuals), the ability to record, replay, cut, and edit gameplay events becomes a powerful tool for explaining the gameplay story.

Evaluation: The game system needs to be able to tell when the momentum shifts, when games are lost (even before they're actually lost like with slipper slope games), and even when power plays are performed. The system needs to be able to trace the cause and rippling effects of actions. This data combined with persistent player stats can be used to construct the real story behind the gameplay.

Even if a game can't piece together the gameplay story as the game is played, it would still be revolutionary if it helped us edit and tell the story ourselves. For a list of record keeping features in games see this article. Gameplay stories are important because we learn through stories especially when they outline increasingly complex and accurate models of the world. Feedback is always an important feature in any learning system, video game included. One of the big reasons why many players have such a hard time improving at a game is because they don't understand how their actions affect their results. When trial and error is a dominant learning strategy used with video games it's obvious that understanding the story of what happened during a trial is a critical step in the process.

In part 7 we'll look at the friction between gamers who focus on gameplay and those who focus on story of persistent player progression.

You May Also Like