Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

It seems to me that there is some kind of diametric opposition between gamers fans of story and of gameplay (even though the categories are often blended in a video game). In this article we'll look at cases where these two side clash for control.

It seems to me that there is some kind of diametric opposition between gamers fans of story and of gameplay (even though the categories are often blended in a video game). Many critics seem to forgive poor stories in their action games (mostly shooters and fighters) if the gameplay is good. And many tend to put up with fairly terrible gameplay if the story is compelling. Gamers also tend to put themselves into either a gameplay or a story camp and, unfortunately, bash the other side. In this article we'll look at cases where these two side clash for control.

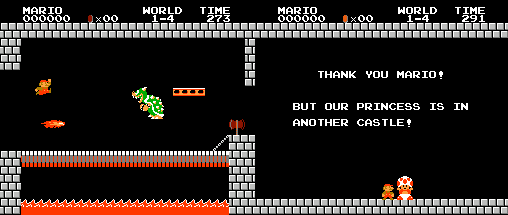

Gameplay on the left vs. story on the right.

With multiplayer games especially there has been great friction concerning fairness in games where players are free to build up their characters (typically in some kind of RPG fashion). The few ideas released about the next Smash Brothers game for Wii U have already stirred questions through the community. Smash Brothers has always been a fighting game where players can pick up and play according to a static set of conditions no matter what system/file they play on. But if players could customize or level up their characters in Smash Wii U, then the foundation on which all tiers, matchups, and skills are evaluated on would be a very different landscape. Some fear such a game would be too difficult to adjust to. I doubt this would be the case. Hardcore (devoted) competitive gamers tend to rise to meet great challenges. The bigger fear is ending up with a game like Advance Wars: Dual Strike where the customization weakens the balance and variety while adding complexity (read more here).

Other examples include free-to-play online games. The entire business model of free-to-play is built around incentivising players to pay money through microtransactions. The game makers provide a variety of items for purchase like cosmetic accoutrement, EXP boosters, better weapons, and other gameplay changing objects. The gamers who seem the most against this kind of model claim that they want their games to be skill based where the victor isn't mostly (or even largely) determined by their willingness to pay up. This is a fairly reasonable request and a tricky balancing act for the developers. Finding the sweet spot between being paid (which is a must) by providing the players with an opportunity to augment their gameplay experience without completely rendering non or less paying players inept is key. Without this balance, the game becomes free-to-lose not free-to-play.

Likewise, champions of real-time, skill-based competition are often opposed to RPG like leveling/customization elements in their games. The idea is they don't want to lose to someone with "equal or lesser skill" just because their opponent puts in more hours into the game. After all, what kind of skill balance would there be if a player can mindlessly grind for significant advantages in competition?

I want to push back on these ideas. First of all, the vast majority of gamers who claim to be all about skill can hardly define what skill is. Because of this lack of clarity it's difficult to explain that competition can sustain a large range of applicable skill. Fortunately, we use the DKART system here. It seems clear to me that practicing in a real time can be very similar to grinding in an RPG. Think about this example in terms of knowledge skill. Whether you build your LTM (long term memory) or MM (muscle memory), lots of practice time is required. When you grind for levels or money in an RPG time is also required. Depending on the task the knowledge skills needed to build LTM/MM or grind is comparable. After all, both take a sort of brute force type approach. When you couple this concept with my theory that all multiplayer games take the same amount of skill to continually play at the highest level and it should be clear that the fear of "unskilled" players beating "skilled players" because of any kind of leveling is unfounded.

The real issue here is that some players simply don't want to lose in certain ways. Whether you win using the most basic moves and strategies or the most borderline, broken, and advanced techniques, there will always be a gamer out there that will complain about how you beat them. It's hard to accept loss when you don't respect the manner in which you lose. It's also harder to respect something you don't understand and can't relate to. And if you're close minded about what skill is, then you're more likely to fall into the trap of labeling what you do as "true skill" and what your opponent does as "unskilled."

Personally, I've won and lost tournament matches because of "one time only" tricks (see example hereand here). These are crafty little techniques that nobody falls for twice. Yes, it stinks to lose. But when you're still learning the game or the community is still formulating rules, you're likely to lose because of anything especially what you don't know. A trick you didn't know. A rule you didn't understand. A character you've never seen with a certain playstyle. Knowledge is power. And what you don't know may kill you. If you're upset when you lose because someone pressed his/her advantage in a way you didn't anticipate, then you should probably stop competing. After all, games with healthy metagamesand communities will constantly redefine what it takes to compete and win.

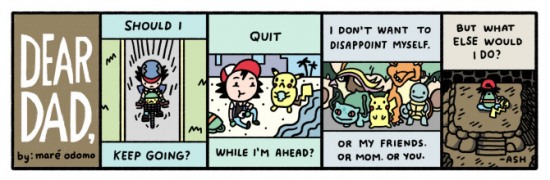

by mare odomo

My Pokemon Story

When it takes time to work for a goal in a video game your journey to obtain reach the goal is a story. Technically, any of your actions during gameplay can contribute to the emergent gameplay narrative. This is part of what I mean when I say that many gamers do not mix story and competitive gameplay. In other words, there's a large group of gamers who seek to separate their journey from their competitive experiences. Just look at the Pokemon community and the responses of competitive battles who I interviewed in my article series.

In Pokemon it can take hours to weeks of work to catch Pokemon, breed, EV train, and raise them to competitive levels. Impatient or time strapped players use hacking devices to simply create Pokemon by punching in numbers into a spreadsheet. On the one hand this gives these players the flexibility to test out new Pokemon teams in minutes instead of weeks. But they also use these devices to maximize nearly all of their Pokemon's stats, a feat that is very difficult and time consuming when done legitimately. When they fight each other, using maximum power Pokemon is a new level playing field. But it's nearly impossible for non-hacking players to compete against them. So, while these competitive battlers have more variety in their games, they lose the significance of their personal adventure/story and some balancing factors.

When I look through my Pokemon that I've raised for battle in Pokemon Black I'm reminded of the long, emergent, and open ended gameplay story that is my journey. I have Pokemon imported from the GBA game Pokemon Fire Red from a play session that started in 2004. Along the years I've gotten help from friends and family alike. My Dugtrio was traded to me from my little sister back in 2007. My Venusaur is from a friend of mine. When I bring him out in battle I say "you can blame Drew for this one!" My Zoroark was a gift from a random player in Mexio that I got through the Pokemon GTS. Half my Pokemon my brother traded me so that they would level up faster. And my awesome Ferrothorn was a gift from my friend and rival, Matt. When Matt uses his special-attack trained Slowbro against me, he attacks with the power of "1,000 Litwicks" a phrase he says acknowledging the journey he underwent battling Litwicks just to EV train his Slowbro.

And it's not just the Pokemon trades that make my Pokemon journey unique. Raising the Pokemon was the product of a village. My brother specialized in EV training while I specialized in EXP training. Do you remember Mustardear from the blog comments? This fellow trainer stumbled across my blog and offered me a specially bred Bulbasaur. Apparently, he had one to spare from his work in one of the 4th generation Pokemon games. A few emails later, we had set up a asynchronous Pokemon trade using the Global GTS system. I'm thankful Mustardear's generous gift and look forward to putting his hard work to the test.

Half of my Pokemon adventure and what I consider to be Pokemon's story is what I make of it. This is not the same as saying that everything a person does is a part of their life's story and therefore part of a bigger narrative. I'm talking about stories contained and expressed completely within the confines of the video game. I'm talking about actions and elements the game recognizes, not the experiences I had outside of the game. Such emergent gameplay stories can be rich, personal, meaningful, and open ended. They definitely stand up against the more directed, less emergent video game stories.

I understand the feeling that some competitive players want to avoid most. They don't want to put tons of work on their Pokemon Teams (or any other game) only to battle and realize that they did something wrong hours, weeks, even months ago. They don't want to lose because they didn't optimize their strategy from the beginning. I know that many people play video games because success is accessible and open to everyone. The idea is with video games you don't have to worry about not being tall enough, physically fit enough, or other factors that we have to live with in real life. The truth is this isn't how it works. Video games are half-real. You bring at least half of your real personhood to the table. This includes all of your quirks, talents, skills, and problems.

Though you may not want to admit it, the reason you may lose in a Pokemon battle probably is because you didn't do something hours, weeks, or moths ago. You probably didn't commit yourself. You didn't take the time or have the knowhow to do it better and now you suffer for it. Maybe it hurts more to not have what it takes and know that you could have had it. Or maybe it's calming to know that hard work is universal. Regardless, instead of avoiding these stark realities, I think it's absolutely important that we embrace them. Because our failures are rich and personal stories too.

In part 8 I'll clear up the following 3 topics: ludonarrative unified theory, ludonarrative dissonance, and sympathetic resonance.

You May Also Like