Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

I've noticed a "meta-genre" of games: Story-Generating Games, including Dwarf Fortress and Left 4 Dead. I look at the games that succeed and this and why, and ask whether this is the real solution to the conflict between gameplay and narrative.

Games are typically categorized into genres based on their basic mechanics - such as Real-Time Strategy or First-Person Shooter - which of course is a great practice.

But lately I've been noticing a type of game that seems to exist across many different genres of games. For lack of a better term, I'll call it a "meta-genre" of game. Marc LeBlanc might argue it should be called an "Aesthetic Genre" of games, as these games are similar not on their Mechanical level, but in terms of a similarity in the kind of Aesthetic experience they produce in the player(s).

I'm talking about "Story-Generating Games."

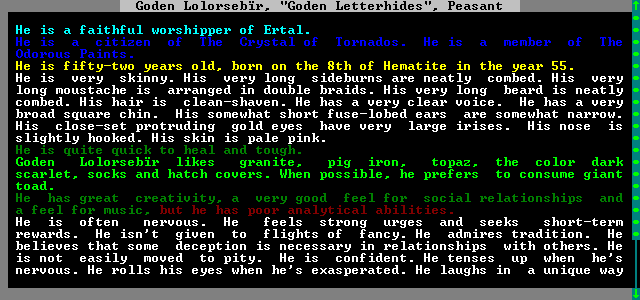

Dwarves remember the stories that happened to them... especially the dwarves of

Forging a Story

Probably the best example of a Story-Generating Game would be the indie game Dwarf Fortress. If you haven't played DF, I highly recommend that you do so as soon as possible. (However, please wait until you finish reading this article. Cause I like it when people read words I write.)

For those who haven't and/or won't played Dwarf Fortress, it's essentially a simulation game, comparable in many ways to both The Sims and SimCity. You manage a tribe of simulated dwarves in a fantasy setting; and you guide the dwarves in digging a new home out of the rock of a mountain, making it self-sufficient, and expanding it.

What this description misses is the amazing granularity and depth of the simulation. The game features a wide variety of systems. For starters of course, the dwarves (and the animals, and invading enemies) feature very sophisticated and interesting AI. But this is just the beginning: there are systems whose purposes range from tracking the health of every body part of every character; to tracking the like/dislikes of every dwarf (as well as things that have happened to the dwarf recently and what their current level of happiness is); to simulating fire (which spreads realistically based on which objects are flammable); to a robust simulations of fluid dynamics (very relevant when your dwarves mine their way into a lava vein - and begin catching themselves, and then everything flammable around them, on fire)!

Just from that description (and its implied story of the Unlucky Flaming Dwarves), you can already see how the richness of the systems - and especially the fact that the systems can interact in so many ways - constantly gives rise to sequences of unexpected, interesting events occurring within the game.

In other words... this game generates stories.

Before I leave the topic of Dwarf Fortress, I should point out that the fact that its tremendous capacity to produce interesting stories isn't an accident. In fact it's a direct result of the creative process of the creators (Tarn and Zach Adams). In a 2008 interview here on Gamasutra, the two brothers point out that they began the game's design by literally writing out stories that they'd like to see happen in the game world; then they simply sat down and began implementing features that would allow the various parts of these stories to occur.

Left 4 Dead is a Zombie Movie Generator!

Dwarf Fortress is probably the most striking example of a story-generating game, but there are many other examples. Here are the most notable examples that come to mind...

The Sims. This game actually shares a lot of similarity with Dwarf Fortress: it's heavily built around simulation; and it's heavily built around AIs that are (mostly) autonomous and which sometimes demonstrate interesting behaviors and even personality. (It almost always makes for a good story when an AI character does something surprising.) The game also has two other facets that I think are important for Story-Generating Games:

Sharing the Story. Starting with The Sims 2, the Sim games were built with elaborate tools to take not only screenshots, but also videos, of the stories that occur in your game. The game has additional features to support sharing these stories with others.

Avatars. The ability to create Sim versions of yourself and your friends in a game tends to make the stories that occur much more interesting. It also makes those stories much more interesting to tell. (It's the equivalent of a father telling his daughter Nell a story in which the main character is "Princess Nell.")

Left 4 Dead. This is an extremely good Story-Generating Game... which is interesting, since in every other way it's about as different from The Sims or Dwarf Fortress as a game could possibly be! Nonetheless, this game has been designed to create a unique but interesting sequence of events for every playthrough. The "AI Director", a core part of the game, exists solely to manage the sequence of events that happen to the players; it's specifically tuned to keep that sequence of events interesting (by ramping up tension and providing breaks), and to make sure that the events are different with every playthrough. Every time you play a session of L4D, you come away with an amazing story... a story that's all your own.

Far Cry 2. This FPS is unique in that it's not built to contain a completely linear story (like, for example, Modern Warfare); instead it would be best classified as an elaborate "Mercenary Simulator." Or perhaps a "Story-About-Being-a-Mercenary-in-Africa Generator." The game takes a great deal of effort to provide a unique experience for each player, and its emphasis on dynamic systems and strong AI characters inevitably lead to unique and fascinating stories. Given that the game's development staff prominently and specifically featured a Narrative Designer, Patrick Redding, it should be no surprise that this game, as well, was designed to generate interesting stories that are unique to each player.

EVE Online. I nearly listed "World of Warcraft" here, but then I realized that the (many) stories that I (constantly) hear about WoW are usually about PvP encounters. Then I also realized that EVE is much more PvP focused than WoW... And then I realized that EVE has produced some of the most dramatic stories in the history of the games industry! (For instance, this one and this one.) It seems that if you give players a multiplayer "sandbox" to play in and some decent tools with which to interact, they'll always produce some very entertaining drama entirely on their own. (And why spend man-hours making a poor AI facsimile of a human mind, when you could just let real humans interact with each other?)

X-Com. I've only played this game for about 20 minutes, but I've heard many stories from players who've gotten deeply invested in the "story" of their squad in X-Com... mostly because the squad members that were doing the fighting (and dying) were usually named after people the player knew! Another example of the Avatar effect mentioned above.

Uncharted 2 has been praised for its story... but there's only one story in that box. (Until you get to the multiplayer...)

What's the Practical Benefit?

Gamasutra is a site for the "Art and Business of Making Games", so I feel like my blogs here should be relevant to both sides of that divide. The business-minded reader at this point is rightly asking: "So why should I bother making a story-generating game? The fact that two random brothers somewhere have made a game about dwarves that has entertained a niche audience and made no money for anyone anywhere doesn't exactly get me pumped! Wouldn't this just be diverging from what the players are used to? Why take that kind of risk?"

Although there are a multitude of good answers to the "why should I innovate?", there's an answer that's especially true for story-driven games: it gets people talking. Literally. When a player experiences a cool dynamic story in a game - a story that is totally their own, and that they know no one else will ever experience - then it's human nature for them to want to tell that story to anyone who will listen!

From a business perspective, this is incredibly valuable: it's not only free marketing, but it's word-of-mouth: the most effective type of marketing there is.

"But why would a player talk more about this kind of game than about, say, Uncharted 2?", my straw man now asks me. "That game had a great story! Better than any dynamically-generated story any game has ever cobbled together."

There are two reasons. First, if I haven't emphasized this enough already: the story belongs to that player. It happened to them and them alone; they're the only one who can tell that story. This gives them a certain connection.

A second, related reason to this is: people don't talk about linear game stories because of spoilers. If I'm recommending Uncharted 2 to someone, I don't tell them all the story beats, because I don't want to spoil it for them. But if I'm recommending L4D2 to someone, I'll say "Oh it's a great game! Let me tell you how it works... and now let me tell you this awesome story that happened to me just last night!!!"

Go With the Flow

My straw man is right about one thing: the linear stories of games like Uncharted can be very good stories, and usually much better than the "game-generated stories" I'm talking about.

But while games clearly do constitute an artistic medium that can be used for telling a linear story, it's also far from the strongest medium for storytelling. In fact, the defining things about games as a medium - like interactivity, immersion, and giving free agency to the player - either do nothing to help tell a linear story, or are actually in active opposition to telling a linear story

Trying to tell a linear story in a game has always felt a little bit like swimming against the current of a river. Storytellers want to relate a linear series of events; but games want to be dynamic systems within which events happen. "Let the player do whatever they want; but make sure that this event and this event and this event always happen", are two design constraints that are inherently opposed.

It makes a lot more sense to stop fighting the current; let it sweep you away and see where it leads you. Games are a medium where each and every player can play and come away with a completely different story. Why do so few games try to enable that, and so many fight it? Perhaps game designers are too much in love with their own stories; we need to focus our authorial control not on creating a linear story, but rather on creating a world in which the player can experience their own story.

I'll leave you with this final, important thought:

..."Unlucky Flaming Dwarves" would be a great name for a rock band.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like