Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

The final –and probably unnecessary- part of an argument for minimizing cutscenes as story-telling devises.

In part 2 I outlined some ways we could move our story telling out of cutscenes and into the game world and mechanics.

And now I want to prattle on some more.

Our audience has come to expect certain elements in the products we make, but we should not feel powerless to shape those expectations going into the future. The fact that there is a demand for the cinematic part of our game/cinema hybrids should not be seen as imperative marching orders.

If we are marching our industry off a cliff it won’t do us any good in the long run. As C.S. Lewis said: “If you are on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road; and in that case the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive man.”

To help illustrate my point, let’s carry this game/cinema hybrid theory to its logical conclusion. At some point we will overcome the uncanny valley and other technical and artistic hurdles. And let’s say we have cinematics that look as real as any Hollywood movie. They are well-acted with grace and intensity. T

hey have well-thought out story arcs that are thematically matched to the gameworld. Well, at this point let’s look at what we have… a cool movie, with a game interrupting it. Perhaps “interrupting” is a loaded word. Let’s say it’s a cool movie with a game punctuating it. Or we can tweak the values so there is more game than cinema.

Now we may have a cool game with a cool movie punctuating it. No matter where the slider lands we still have two incongruous elements. They may complement each other. But they are two separate types of experiences spliced together.

We all long for the ultimate gaming machine that is idealized in the Star Trek Holodeck. A device that lets anyone become any character in any event or story. (With the occasional downside of creating homicidal sentient beings who will turn off the safeties and attempt to commandeer the ship.)

Contemplating this device is a useful exercise for a designer. Let’s imagine we get to design a holodeck game. What is it going to be like? Would we make it like Uncharted or Mass Effect, where the play is stopped for several minutes at a time while your character is puppeteered into doing and saying things you have no control over? Even with its photographic, perfectly acted glory, these interruptions would seem ridiculous, right?

So why are we so happy with this hybrid now? Maybe it’s because there are plenty of other media that have similar kinds of couplings. Picture books have text and images that complement each other. Musical recordings often have evocative cover art and lyrics laid out in creative and cool ways. So if I’m consistent I should be opposed to these combinations as well, right?

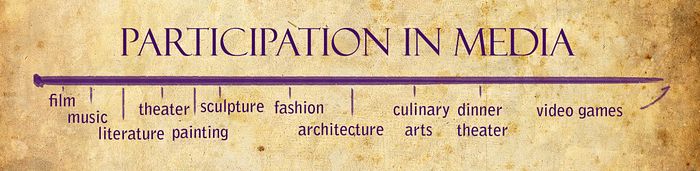

Well no. And here’s why. Books, pictures, music, and text all share something in common. They reside on one side of the Participation Continuum. If you imagine a line with all the various artistic mediums charted, you can pretty easily see which ones are require more participation.

Participation In Media

I’m being careful here to not create a false binary system where I lump some mediums into a non-participatory category, because such a category cannot exist. All art must be experienced and processed in a mind, and this process is participatory to some extent. We must interpret the signals coming into our brains according to some system. So we are participating in creating a new artifact by bringing our mental faculties to bear on an artist’s work.

But there is something that games bring with them that skyrockets them so far above and beyond every other medium that it’s almost silly to put them on the same graph. And that is the fact that other players, or a programmed, designed system will interact with a player. No book or music or architecture can do this in more than very rudimentary ways.

Products such as a choose-your-own-adventure book, or light switches in a building, or salt and pepper shakers with a meal. These invite our participation, and the interaction we have with the artifact objectively changes as it responds to our input. And of course people can impose games on these artforms. Parkor finds new ways of instilling kinetic movement to architectural space.

Drinking games will highlight specific words in movies or tv shows. And of course you can dance to music in game-like ways, doing specific moves when certain cues occur. These interactive procedures can bump these media up the Participation scale a bit, but nowhere near where videogames reside on the scale. Because they are all reactions, not interactions.

Most of these other media are created at some point and distributed to an unknown audience. The author/artist/designer has no way to directly accept feedback from the audience and alter the content accordingly. Especially in literature, music and film, there is practically no room for interactivity at all. If I scream at the screen in a movie or circle every tenth word in a book, the media has no way of registering these inputs and reacting according to some rule set. They simply ARE. They do not BECOME. (Except existentially or subjectively.) In short: they do not interact.

I think that this important distinction is so often overlooked because we have all been conditioned to interpret artistic artifacts, rather than to participate in them. Or rather: the more participatory a medium is, the less likely we are to consider it art. Humans like to put things into neat groups. It helps simplify this crazy world.

We categorize film, books, music, dance, sculpture, photography, poetry and games in the same general headspace. But I think we could easily pick out games from that lineup of artforms with a simple game of “one of these things is not like the others”. Yet we continue to pretend that our form can be mixed well with all the others, just like dance-and-music, poetry-and-books, film-and-music, etc. One could conceivably mix game with dance, sculpture, poetry, and music and get some interesting results. But would they create good art? Maybe. Maybe not.

But I want to be fair and examine ways in which the influence of story-telling mediums has brought value to our medium. From the days of gladiatorial combat -and probably before that- humans have found ways to incorporate a broader context into the games they’ve played. (Many gladiator events were staged to be recreations of historical and mythical battles.) And here is where we can examine what parts of linear-crafted-story-telling share enough of the design language with games to be incorporated in an artistic and elegant way.

But we should not feel shame for being unable to artfully incorporate crafted-story-telling into games. There are many other artforms that speak powerfully to the human mind that are not story-driven. There is architecture, fashion, landscape design, culinary arts and others. None of these artforms are worse off for not having a narrative. And none of them would be improved by shoehorning a storyline into them.

No critic complains that the Eifel Tower fails for lack of story-telling. No food critic says the steak would have been better if he felt there was a narrative behind the meat. Though, all of these artforms can be springboards for extracting narratives or stories. The artifacts they produce can be interpreted creatively to "tell a story", just like the events of a game can do. But that does not make them "story-telling" mediums.

Then there are the classical arts like painting, music, dance, and sculpture. In these forms you have a range from totally abstract to perfectly representational. But they are still not story-telling-mediums. They can represent stories. They can illustrate stories. They can function as icons for stories. But even in their most iconic -such as religious paintings, sculptures and stained glass- they can only convey limited bits and pieces of a real story, not tell a complete story on their own.

So I think the fact that artistic profundity can be contained in non-story-telling mediums should encourage us as game designers to stop chasing Hollywood. Let’s grow up and be our own medium. Let’s provide profound and moving experiences using our unique strengths. Stories are a fantastic thing. But if we tap into what it is that MAKES stories fantastic, we can discard the shell.

So why IS story such a powerful concept? I think it is because they are fundamental building blocks of our life. Stories resonate with us because they are structured like the way we WANT our lives to be. They feature a protagonist who faces a challenge, then usually overcomes it. (Of course there are stories that deviate from this template, usually experimental or avant-garde affairs, and generally not very popular.)

From the time we are infants attempting to gain control of our flailing limbs, to our time in school attempting to pass a test or get that cute girl in the front row to notice us, to the workforce where we compete for the best job and highest pay, our lives are defined by obstacles and challenges. Our desires are constantly thwarted by them and we obviously want to succeed in overcoming these challenges. That is why we love stories. They are the primal expression of our deepest longings.

And what goes on in a video game? A protagonist is faced with a challenge and usually overcomes it. So a game taps that same primal hope, but in a much more powerful way than a story can, because the protagonist is mostly YOU, the player. You are not projecting your hopes onto a character. You are living a metaphor for your hopes in actions and choices that you are making.

You are taking your destiny into your own hands in a game. In a story you can only root for the good guy and hope the author is nice to them. Your catharsis is limited by a third party and your ability to empathize with a fictional character. In a game you can empower the good guy to win. You are in fact, the key to success, so the resonance with the life metaphor is so much more powerful.

So in summary: We don’t need story in our games to create meaningful, compelling experiences, and if we want story in our games there are better ways to do it than interrupting the gameplay with cutscenes.

You May Also Like