Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

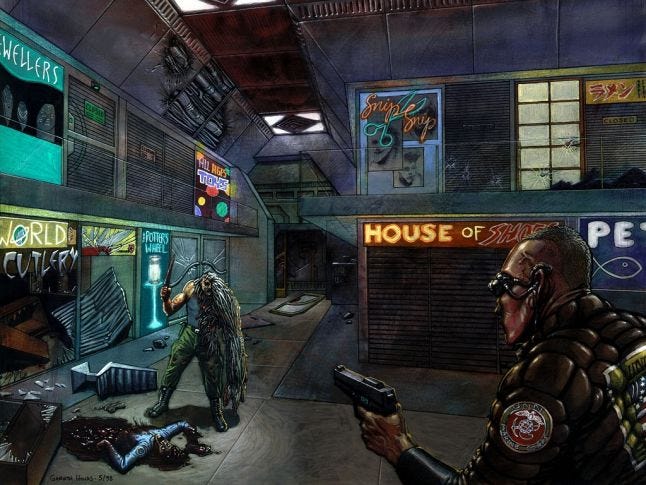

15 years ago, Thief saw a third outing in a year hosting the likes of Half-Life 2. Doom 3 and Far Cry. In this retrospective piece, Bethesda Softworks alumnus and writer Michel Sabbagh explains why Deadly Shadows should be celebrated.

Holding a key, you may infer the existence of a lock. However, do not make the mistake of assuming that yours is the only key. - Handbook of Scribes

They say that third time's the charm when it comes to tasks and events in life. But what they omit to say is that trilogies, even the ones concerning beloved properties, can oftentimes — and pardon my French for this one — screw the royal pooch in their finals.

Yes, I know you can have your Halo 3/Toy Story 3 and play/watch it too, but please bear with me.

Superman III, Shrek The Third, Dino Crisis 3, Dead Space 3... Due to development issues and/or an inability to keep one's feet firmly planted on the visionary ground that defined the artwork in question, threequels may find themselves unable to carry the torch borne by its predecessors, resorting instead to clumsily dropping it in the proverbial pond as a result of tripping over a dumb lump of rock.

This may lead to two outcomes: Either the talents own up to their errors and are given a chance to redeem themselves with a fourth outing, or the critical and/or commercial damage proves so colossal it spells doom for the franchise's and, more disappointingly, the creators' future. The latter scenario's indubitably damning. It can seem especially unfair when you don't get to have a third cheer.

Unfortunately, that's the kind of hand Looking Glass Studios was dealt roughly three gaming generations earlier.

On the heels of the critically acclaimed but commercially lukewarm Thief II: The Metal Age, the Cambridge, MA studio — famous for immersive sim darlings such as the likes of Ultima Underworld and System Shock — faced gloomy prospects. Fiscal woes, a lack of external funds, and the cancellation of deals with Sony and Eidos Interactive rendered the outfit unable to remain operational at the turn of the century, leading to the company's demise on May 24, 2000 when Paul Neurath and Steve Pearsall broke the news to their colleagues and the public.

It was a dark time for the ones responsible for pioneering systemic game design and storytelling devices in the 1990s, as well as the master thief Garrett who dubbed the palpable kind of dark his best chum as he scoured the minimalistically titled City for riches and opportunities to subdue overly chaotic and authoritarian figures. Would everyone's favorite kleptomaniac fade into the shadows abruptly and in perpetuity?

According to Eidos, no.

In August of that same year, the publisher purchased the IP rights to the Thief franchise so that one of its subsidiaries, Ion Storm, and the likes of Warren Spector (of Deus Ex fame) could potentially do justice to what Looking Glass Studios had started back in 1998, the year that revolutionized the industry with Half-Life, Ocarina of Time and, of course, Thief: The Dark Project.

So what happens when you hand development duties on a third installment to another developer, one responsible for virtual concoctions such as the infamous Daikatana and highly divisive Deus Ex: Invisible War?

You get Thief: Deadly Shadows, a threequel that, despite a change in developers, successfully adapts the series formula for a new era while also hosting its fair share of positive contributions, both mechanical and presentational.

And released (almost) precisely four years — on May 25, 2004 — after Looking Glass's demise. Quite eerie.

I recall first learning of Thief's existence when my college freshman self stumbled upon Gmanlives's retrospective look at the original installments back in 2014. Having grown up with stealth titles and steampunk offerings such as Splinter Cell and The City of Lost Children respectively, I couldn't help but be intrigued by the atmospheric tension and exploratory improvisation Thief leveraged, with its being nearly 20 years old (at the time) further amplifying its novelties. A jaunt to GOG and some technical fine-tuning later, I was primed to dive into Looking Glass's first-person stealth 'em up.

And what a dive it was.

As my past ramblings about the first outing suggest, the Dark Engine-powered Thief entries offered something wholly special in terms of storytelling and environmental craftsmanship, which only similarly bold releases like Silent Hill 2 and Planescape: Torment could supply.

Whether it was the brilliant intersection of mechanics and narrative design seen in locales such as Constantine's Mansion, or the lived-in aura of the City felt through guard conversations and collectible notes, The Dark Project and Metal Age pulled no punches when it came to fully immersing the participant in a universe whose ambiance and world-building could suitably rival its literary and filmic counterparts.

But with Ken Levine's and Laura Baldwin's initial input being absent this time around, I went into Deadly Shadows with cautious optimism. On one hand, I was confident that the original plans for an open-ended city and a more intimate look at Garrett's former home, that of the Keepers, would make a smooth transition into the final product (considering that Ion Storm hired ex-Looking Glass staff to tie up loose ends).

On the other hand, I was worried that the inclusion of the Xbox in the development pipeline would negatively impact the scope, detail and atmospheric potency of the previously daunting levels, which played a sizable role in selling me into the rich world that lay within and beyond the navigable space in previous titles.

What I ultimately got, however, told a different tale.

Set some time after the Mechanists went belly up in The Metal Age, Deadly Shadows follows the exploits of thieving meister Garrett, who was taken in by the balance-loving Keepers as a youngster before breaking off to fulfill all sorts of kleptomaniacal fantasies (including stealing a sentient Eye that ironically led to Garrett's own peeper being plucked off his countenance two games earlier).

Unlike past entries — which revolved around the schism between the technocratic Hammerites and nature-worshiping Pagans — Deadly Shadows shifts its attention to the same organization that trained and watched over the master thief before the latter's departure. After flexing his proverbial muscles in sundry sectors of the clockpunk metropolis dubbed The City, Garrett meets up with Keeper Artemus and is tasked with, you guessed it, stealing priceless artifacts in exchange for riches and some time-tested prophecies thrown in for good measure.

Thick as thieves, then.

Once again, the writers and Stephen Russell do justice to Garrett's solitude and individualism by tapping into the sense of pride and independence that had him butt heads with noblemen, organizational higher-ups and even supernatural entities.

From the dry wit he dishes out during gameplay and critical story segments to the monologic briefings that highlight his knowledge and feelings about the jobs he takes up and their locations, the master thief hardly misses a chance to make his confidence known to the participant and those around him, deftly setting the mood for what transpired and is to come. It promotes a feeling of reflection, perspective and progress that spotlights his professionalism, experience, and even own brand of humanity.

It also helps that, on a personal note, I saw myself in parts of Garrett's assertive disposition. As someone who oftentimes felt at odds with my peers and environs in college, Thief and its leading star served as conducive refuges from the muck reality would pelt at me, allowing me to immerse myself in the role of an individual who'd rather keep to himself and self-actualize in his respective way than become the center of attention and follow the hoi polloi.

The fact that characters like Garrett also birthed some of the observational mannerisms I still carry to this day speaks volume of his character's infectious repartee, which hardly loses its potency in the face of conspiracies and sudden turns of events befalling the Keeper organization as it wrestles with a minatory force.

Compared to the collectivistic figures seen in other genres such as role-playing games and even shooters (looking at you, Overwatch) who may act as fitting companions and role models for players, Garrett can seem like a doggone hermit bereft of human values, with his estrangement from the Keepers bolstering that impression (and mirroring my experience with my peers).

But as the later parts of this post and other opinion pieces on Garrett's detachment from an indifferent and intimidating world illustrate, there's more to his personality than just his being a crafty outcast, with the unadulterated fantasy of shadowy sneaking and the inclusion of full bodily awareness helping even more skeptical participants immerse themselves in the role of Garrett.

And craftiness is something they will have to leverage on their tenebrous journey. Unlike most City dwellers, Garrett doesn't fear the unknown. He embraces it.

The original Thief outings were celebrated for going against the grain in terms of what a first-person title could accomplish. Whether it was prioritizing methodical subterfuge over wanton carnage or leveraging spatial details for storytelling purposes, Looking Glass's magna opera presented a world dripping with juicy opportunities for creating a subtle but effective dialog between the participant and the environment as the former went about bringing down the property value of the locales they infiltrated, including the sprawling Bonehoard and opulent manors of Bafford and Ramirez.

But as much as I enjoyed exploring the levels back in the day and as with all risky endeavors, there is a wrinkle about the City's underbelly — particularly its more verdant and secluded quarters — that partially contributed to the series' relatively niche status in the realm of (stealth) gaming: Overly large and labyrinthine maps.

Either due to the arcade-like trend of tangible challenge seen in pre-2000s releases or missynchronizations between Garrett's abilities and the repertoire of obstacles he was presented with, missions could potentially overstay their welcome if one let the tension override their planning and cause them to impulsively traverse their surroundings.

The likes of the Lost City and Beck o' the Wills may've proven fetching, but their scope and complexity had my younger self spend hours just trying to get my bearings, with my appreciation of the presentation and story alone anchoring my resolve as I sneaked my way through long corridors likely used to mask data streaming and load times.

Deadly Shadows sidesteps many of those legacy boo-boos.

Yes, the vanilla experience suffers from mid-level loading screens courtesy of the Xbox's hardware limitations (unless you're like me and installed the Sneaky Upgrade mod on PC) and yes, the breath-robbing scale that heavily contributed to the atmospheric tension in the past has been curtailed a fair bit, but what Deadly Shadows lacks in size, it more than makes up for in dynamism and content density.

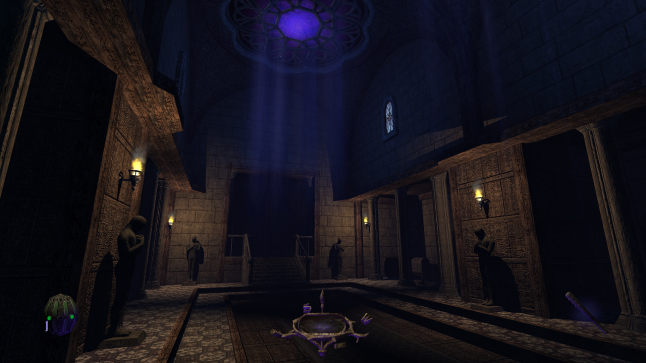

From the sprawling Pagan Sanctuary that encompasses verdant sewers and ruins to the Sunken Citadel that has amphibian humanoids roam its cavernous quarters, Ion Storm's take on the series' level design formula respects the intricacies of their predecessors through the contextualized distribution of loot around the maps (e.g. Keeper Rafe's remains in the aforementioned Citadel's library and the glyph marks he left behind to guide himself) and the interactions between NPCs minding their business and patrolling their abode.

The smaller maps meant that such details became more noticeable in my eyes, and it led me to associate certain objects and rooms with specific sightings as I spied on unsuspecting figures. Whether it was the tables hosting card games between the guards in the middle of a storm or the bunk beds whose level of comfort was only matched by the vividness of their users' dreams, Deadly Shadows's props take on an image and defining trait of their own that enhance the series' scene-setting aspects while still letting gameplay necessities sync with the reality of the game’s locales.

Such locales also benefit from what's happening behind the scenes. With a move to newer hardware and more modern technology, Ion Storm's leveraging of a modified Unreal Engine 2 imbued the environment with more dynamic lighting that not only looks convincing, but also begets more windows of opportunity for Garrett.

Having to keep an eye on moving shadows (courtesy of torch-wielding guards and other mobile light sources) on top of worrying about dousing stationary lights means that I needed to be more active than ever before, making Garrett more characteristically nimble than he was in the past when wobbly Dark Engine physics and audiovisual limitations could put him at a disadvantage.

Thankfully the engagement I felt as a result of my avatar's vulnerability remained more or less intact due to the preservation of Garrett's physical weakness (with the removal of his trusty sword in favor of a dagger further reinforcing the series' preferred playstyle).

The shabby maps, insightful collectibles, rift between poor and rich areas in terms of surface material/light sources, and fruitful eavesdropping that Looking Glass implemented for the sake of exploratory improvisation and subtle storytelling make a return in Deadly Shadows, with the addition of an open-ended City environment between missions fleshing out the world-building that was initially felt vicariously through NPC conversations.

By broadening the space in which I could tread, Deadly Shadows also made the franchise's trademark foreshadowing and scene-setting more palpable. Now instead of imagining what the Bear Pits would've looked/sounded/felt like, I could look forward to stumbling upon people and places mentioned off-the-cuff.

More on that later.

Speaking of off-the-cuff, being able to freely saunter around the likes of South Quarter, Auldale, and the infamous Old Quarter helped deepen the series' immersive sim roots in (un)predictable ways. When I realized that I could break into several houses and establishments outside missions to rake in the money and spend it at back alley stores, I began to understand how Looking Glass would've originally expanded the Thief formula before Ion Storm stepped in.

On top of creating more "water cooler" stories that ranged from messing with patrons on the second level of the Stonemarket Tavern to breaking into Fogerty's Gold Smithery while being chased by the City Watch, having accessible interiors also removed whatever artificial facade the City may have embodied beforehand, allowing my kleptomaniacal self to become more invested and included in Thief's inhospitable setting.

Coupled with some moody sound design (courtesy of Eric Brosius and Mark Lampert, among others) and the aforementioned lighting model, Deadly Shadows's more cramped spaces embody the kind of lived-in aura that has Garrett become one with his surroundings. Now instead of having a dynamic avatar navigate a mostly static environment, both the participant and their environs mingled with one another as the former unearthed every nook and cranny of the latter, solidifying the symbiosis of improvisational exploration and environmental storytelling that made the series' backstory and ambiance so alluring.

All of these design and environmental facets make the act of uncovering information one's not supposed to know all the more gratifying, especially in more dramatically charged levels like Rutherford Castle where familial intrigue contextualizes Garrett's interloping. This highlights one of Deadly Shadows's other major contributions to the series that pleasantly took me by surprise by adding another layer to my emotional involvement: Interpersonal sequences.

Being a thief of the night may be a solitary endeavor, but that hardly means one's unlikely to stumble upon colorful and dramatic banter in their line of work.

Given The Dark Project's role in popularizing the mechanic of eavesdropping on NPC conversations, it's no surprise that Deadly Shadows would make use of its extra horsepower to make Garrett's friends and foes more entertaining to witness.

Whether it's learning about the disagreement between a scholar and his master in the Keeper Library or following the tale of two guards trying to deal with a stubborn injury, Ion Storm's outing hardly misses a chance to have me take my hands off the mouse and keyboard just to better appreciate the mix of foreshadowing and scene-setting in the dialog.

As much as I loved perusing the documents I scavenged in the earlier titles, I knew that technical limitations limited what Looking Glass was capable of doing in terms of baking the narrative into the environment itself.

Ergo, Deadly Shadows's attempt to strike a better balance between written and spoken words with regards to dishing out gameplay and lore information struck me as well-thought-out, with the quasi-open world expanding the field of possibilities for lively and mysterious exchanges that can even affect Garrett's progress.

When I learned that I could go as far as to knock out scribes to bolster the votes against beefing up security near a specific room in the Keeper Compound, I couldn't help but vary my tactics just to see how things would've turned out differently.

It's that level of experimentation and spatial manipulation that makes Garrett such a fun character to play with and as, with his laissez-faire actions also presenting an opportunity for some moral role-playing that the game recognizes at certain points. With the removal of difficulty-based restrictions on kills, a specific facet of Garrett — one that partially contributed to the series' gameplay-narrative synergy — is called into question: His scruples.

The avatar's being physically weak in prior entries wasn't just because the developers wanted players to adopt the then-novel approach of non-lethal first-person gameplay. It was also a character-reinforcing statement that highlighted the fact that the protagonist was a robber, not a murderer, something higher difficulty levels reflected.

This is what I meant earlier when I said that there was more to Garrett than his crafty and anti-social comportment, and Deadly Shadows offers players a chance to channel their inner gentle(wo)man thief by acting in accordance with their avatar's moral code.

Take the Overlook Mansion, for instance. Like Bafford's and Ramirez's Manors in The Dark Project, this seaside estate represents Garrett's favorite specialty when it comes to taking monetary burdens off of his targets.

But the mission, for all its callbacks to previous entries, adds a ludonarrative spin to the formula in the form of Captain Moira's Widow and her growing estrangement from her staff and caretakers. Taking into consideration Garrett's code and Deadly Shadows's laxer penalties, the participant can either feel pity or opportunism upon encountering the dejected ruler of the estate as one of their objectives involve her inheritance.

This is where the spin comes in: Should the player defer to their better nature, they can choose not to steal the inheritance (unless they're playing on Expert which requires that all loot be garnered) and leave the widow be. Additionally, they can honor the NPC's request for a bottle of wine by fetching one in the kitchen and bringing it to her, leading to her gratitude overwriting her annoyance at Garrett's robbing of her domain in the form of inebriating loot and a thank you note delivered straight to the thief's apartment later on.

Or you could just steal the inheritance and face the wrath of her loyal thugs. Whatever floats your goat.

Giving players the free choice to react to NPCs in a way that doesn't involve noggin-whacking or ghosting helps them become better invested in Garrett's professionalism and humanity, with the optionality of Moira's request making it stand out from other benevolent endeavors such as helping a ghostly girl and assisting the Keepers in the middle of their crisis (making the master thief an altruistic egoist at best).

On a narrative level, actions like these separate Garrett from the authority figures and brigands dotting the City. He may be an outlaw, but that doesn't mean he can't have a heart of gold, something that other fictional criminals such as Lupin III and Aladdin have in common and that may be doubled down on via non-lethal and ghosting playstyles. Like I said, there's more to a thief than meets the eye.

"Then what could possibly set Thief apart from other, infinitely more popular outlaws and stealth sims out there!?" you might ask.

Well, one gander at Immersive Simulant's playlist will answer your line of inquiry with a golden word.

That word is atmosphere.

Having grown up with palpably moody games such as Half-Life 2, F.E.A.R. and BioShock — not to mention written about the topic — I have come to gauge a title's memorability and quality partially by the strength and uniqueness of its ambiance. Through a mixture of sound, lighting, open/narrow spaces and shifting motifs, a work of art can convey a great deal of its theme and tone through the goings-on and attention-to-detail baked into the environment.

This is something Looking Glass expertly grasped with the first two Thief releases and Ion Storm deftly carried on the tradition by making full use of a dim but arresting art style and Unreal Engine 2's advanced lighting and sound models.

While replaying the game to reacquaint myself with its core strengths, I ended up idling about on more than a few occasions as a result of the atmospheric potency enveloping me, from the monolithic Clocktower overshadowing Stonemarket to the depths of the Sunken Citadel hiding under the Docks.

When played on modern PC hardware, Deadly Shadows can still dazzle the senses with its medley of background noise and colorful lighting, a testament to the series' dedication to first-person immersion built around Garrett's vulnerabilities and spatial narratives.

This is hardly unintentional: As I implied before, the key to Thief's success as a burglar simulator is its doubling down on the player's emotional involvement, i.e. the desire to believe in the reality and verisimilitude of something fictional.

While hardly top spot material for the Mercer Quality of Living Survey, Deadly Shadows's rendition of a daunting metropolis and rural outskirts stuck in the doldrums bears an eerie sense of beauty not too dissimilar to the Zone's from the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. titles, turning what would constitute loneliness in many into an uncannily meditative bout of solitude.

It's this sense of beauty that keeps Thief from making the player feel emotionally numb like in many other dark artworks that may prove exhausting with their gloominess and lack of contrasting comeliness (The Road and Condemned 2: Bloodshot are guilty as charged).

Coupled with the oftentimes risible NPCs populating the mission areas and streets, the ambient bliss's looming presence seemed like an intentional inclusion on Looking Glass's and Ion Storm's part to convey a feeling of wonder and even hope, with warm and cool hues of blue and yellow bathing the scenery and punctuating the rift between industry and nature.

That kind of audiovisual detail, both minimalistic and elegant in its depiction, is the sort of environmental storytelling only the likes of the aforementioned City of Lost Children, Brazil, Voodoo Vince and even books such as Something Wicked This Way Comes can hope to match with their own styles and techniques. The universality of that ambient component and Deadly Shadows's amplification of it speak volume of the title's darkly fantastical appeal and image among other mid-2000s games and works of a similarly wicked nature.

While the argument can be made that releases in that era generally jumped on the same higher-fidelity bandwagon as Deadly Shadows with varying success — let's be frank, bloom and shiny textures haven't aged gracefully — that hardly dampens Ion Storm's almost timeless efforts, with the architecture and clockpunk style elevating the audiovisual presentation beyond raw technological power.

A rare feat for games with more realistic graphics, you might say, but Deadly Shadows's focus on having the participant play it low and slow means that spatial details will be held to greater scrutiny compared to faster-paced affairs, hence the need for ambient tension and a presentation conducive to the former.

Like my love of Garrett, I became enamored of atmospheric locales thanks to my introversion and paying greater attention to my surroundings as a result. Whether it was because the world itself was sprawling, maze-like or hosting peculiar sights and sounds (or just my being sensorily sensitive), I always took an interest in things that stood out to me, which mirrors the master thief's instincts as he goes about looting his surroundings and looking for passages and landmarks that make his job easier.

It's not uncommon for one's mood to be tethered to that of their environs, hence Deadly Shadows's wisdom in doubling down on that psychological link between the individual and what they draw from the environment.

And this is where I may wax lyrical about that place.

No analysis of Deadly Shadows would be complete without it.

So infamous is its dread that PC Gamer crowned it the only level they wrote a single article about.

It even got emulated in the (lesser) Thief reboot.

Welcome to the epicenter of atmospheric tension. Welcome... to the Shalebridge Cradle.

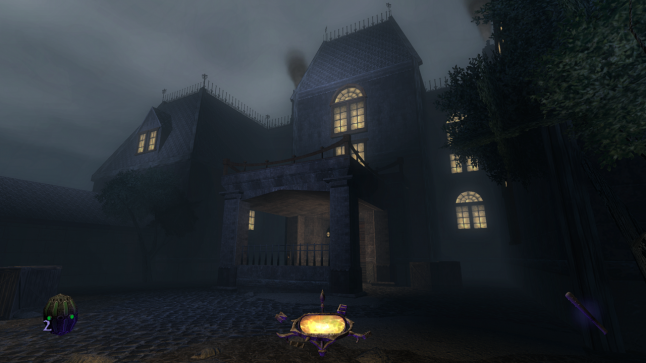

You see, following the sizable impression The Dark Project's Haunted Cathedral made on players, Randy Smith sought to crank things up to 11 by blurring the lines between what's safe and what's dangerous, the same lines that previously took on the form of musical changes in the first two installments. For him and his colleague Jordan Thomas, the Cradle was much more than a haunted house: It was interactive horror design in its rawest form.

Like Constantine's Mansion in The Dark Project, the Shalebridge Cradle serves as a test of Garrett's capabilities, with the participant having gotten used to the master thief's cocksure attitude and set of skill in past missions. But unlike that mansion, the player will only be able to reach the abandoned orphanage/asylum right before the story wraps up.

Therefore, the participant will have developed a greater understanding of what constitutes a well-heeled establishment and supernatural settlement compared to their initial experience with Looking Glass's offerings. "Swell," you might say. "I'm so eager to rob that so-called madhouse. Surely the rumors 'bout it were overblown."

And then you head inside and realize that you've played yourself.

What makes the Shalebridge Cradle so terrifying compared to its forefathers is the way Deadly Shadows foreshadows the player's venturing into it in the form of random conversations and landmarks that remind you of its presence without even giving you a chance to see it in the flesh prematurely.

As unsettling as its thematic predecessor, the Haunted Cathedral from The Dark Project, was, Garrett could still get real close to its exterior early on before getting a chance to dive down into the belly of the beast. With the Cradle, however, the player must rely on their gut instincts to gauge the wickedness of the establishment, allowing Ion Storm to preserve the element of suspense.

This brings me to the Cradle's first commonality with Constantine's Mansion and the Haunted Cathedral: The way it toys with the player's expectations by first exposing them to the kind of ambiance and layout they'd expect from what they've heard and been told before pulling the rug from beneath their feet.

When you first trigger the mission "Robbing The Cradle", your avatar begins the level facing the towering facade of the institution itself. You immediately register the idea that it houses its fair share of terrors, the same way one would expect Constantine's Mansion to contain guard quarters, bedrooms, dining halls, and inner gardens. As you venture into the basement and the rest of the Outer Cradle, you realize that something's amiss, and I ain't talking about the ominous soundscape or the staff's failure to pay the electricity bill.

Long-time fans of the series will probably be familiar with the legacy idea that bodies of water — such as the ones present in the Lost City, Opera House and Cragscleft Prison — acted as bulwarks between safe and dangerous areas. Given Mother Nature's absence on unholy grounds, you might think that the storm cellar near the starting zone is that level's bulwark. And you'd be right... regarding the first half.

This is where the lines blur between safety and danger, which is what gives the Shalebridge Cradle its unpredictable and cruel nature. Even though the Outer Cradle clearly looks to be inhabited by malevolent forces (which it is, just not on a material level), there are no enemies to be encountered in the early portions of the mission.

Instead, your mind fills in the supposed blanks in the facility that are generated by the fear of the unknown, and it can get to the point where one may be scared of their character's own voice. And that's not mentioning the narrative, which you are free to piece together if the tension hasn't overridden your desire to explore. I mentioned earlier that the Shalebridge Cradle was an asylum and an orphanage, but a firsthand playthrough of the level will reveal the reality behind what I meant to say.

Between the notes detailing life among the orphans and patients, and the evidence of heinous rough-housing characteristic of the mental cases (you'd be forgiven for wincing at the sight of ashes in a baby crib), the Cradle has a lot to unpack from a storytelling perspective, with the collectibles and space itself revealing an especially morbid tale of nonsensical treatments, ill-advised practices and unceremonious ends. The atmosphere speaks for itself, relaying the fallout of a failed institutional experiment to Garrett.

The Puppets — downtrodden reanimations of the patients who embodied different kinds of lethal idiosyncrasies back in the day — roam the Inner Cradle, their bloodlust bolstered by the building's sentience and their presence made known by the flickering of lamps as they near them. And when those lights aren't malfunctioning, they are subtly dimming and brightening, almost breath-like in their rhythm as if... the Cradle lives on.

And so do its damned residents, who take you by surprise when the feeling of relief you felt at the lack of enemies in the Outer Cradle pop out of left field in the other half. At this point, the level begins contorting the player's expectations, akin to how Constantine's Mansion became more twisted as Garrett ventured further into the manor. When lighting itself becomes a frenemy by explicitly signaling approaching threats while still acting as a medium for atmospheric omnipresence, gameplay dynamics begin to shift and become scrutinized.

The inability to permanently incapacitate — let alone kill — the supernatural prowlers (who come in more than a single variety, mind you), the blurring of lines between safety and danger via the audiovisuals and gameplay information, the need to manipulate time itself to escape the Cradle as it begins remembering your presence and trapping it within its confines...

Past levels may've spotlighted Garrett's vulnerabilities to certain extents, but the abandoned madhouse amplifies them to a dwarfing degree. Coupled with the gut-churning history learned via collectible notes and the leveraging of scenic details to showcase player progress and historical goings-on, the series' brand of emotional involvement comes full circle with Deadly Shadows's penultimate level.

"Robbing The Cradle" works so well as a Thief mission not merely because it has the player on edge and discombobulated, but because it isn't afraid of breaking down conventions established by the mechanical and narrative boundaries the player got used to earlier in the title and series. And yet the gameplay and storytelling don't suffer from this survival horror shift like they did during The Dark Project's paranormal and Tomb Raider-like environments because the following lessons are still upheld:

Use exposition subtly to present world-building elements

Set the tone for each level and design them in a way that communicates

progress

Let players feel as if they’re learning things they’re not supposed to know

Use mechanics to communicate story and player-environment dialog

Alright, lyrical waxing over. Otherwise the Shalebridge Cradle will go from making one uneasy to making one mad.

Deadly Shadows is anything but perfect. Some of its more fetching innovations — including the City's free-roam structure and the Hammerite-Pagan faction system — felt rather undercooked given the game's narrative linearity, the removal of rope arrows and swimming flattens the spatial depth and exploratory improvisation seen in past Thief titles to a certain degree, Havok can create floaty and unresponsive physics in the player movement model and environmental interactions, and the story itself lacks some of the subtlety and symbolism first depicted in The Dark Project.

But does that justify the fact that Deadly Shadows, like its predecessors, floundered on a commercial basis in spite of its critical warmth? Certainly not.

Like Garrett himself, the Thief series eschews the spotlight in favor of sticking to the shadows and working its magic surreptitiously, letting the likes of Hitman and Metal Gear Solid enjoy the conspicuous fame provided by audiences. But when the dust settles and all is said and done, the fruits of Thief's labor yield something of a mark embedded upon the ground it walks, with titles such as Splinter Cell, Dishonored and The Chronicles of Riddick bearing many of the master thief's gameplay innovations.

Deadly Shadows, in sundry ways, upheld the principles of environmental storytelling and atmospheric tension, tenets whose malleability enable their smooth transition to other mediums such as cinema and literature. In spite of their predilection for solitude and secrecy, Garrett and the Thief series should still be celebrated for demonstrating what a gameplay-narrative synergy can bring to the table, for taking creative risks with their approach to first-person endeavoring, and for encouraging audiences to take it low and slow so they may better appreciate the scenery and its inhabitants, further solidifying the bond between the participant and the world they immerse themselves in.

With more modern titles following in Thief's footsteps in terms of cohesively fusing mechanics and storytelling — especially given the presentation of additional themes and topics of interest and relevance in the world of entertainment — and the intensification of worldwide tribalism à la Hammerites v. Pagans, perhaps the time to revisit the former black sheep of the stealth 'em up series and don the shoes of an observing and chaotic neutral kleptomaniac couldn't have come more opportunely.

Sometimes the advances, good deeds and things we take for granted in life and the arts come from the unlikeliest and most obscure of places, including the deadliest shadows.

It is not an easy thing to see a Keeper... especially one who does not wish to be seen. - Garrett

Let me know what you think of my article in the comments section, and feel free to share this post and ask me questions! I’ll do my best to get back to you as promptly as possible.

Thief: Deadly Shadows is available on both GOG and Steam for PC owners.

Personal blog: https://michelsabbagh.wordpress.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Watfen64

LinkedIn: https://ca.linkedin.com/in/sabbaghmichel

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Michformer

Email: [email protected]

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like