Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"Having monsters that have to be dealt with in different ways that require you to stop moving and fiddle with your phone was the core for the 'difficulty' of survival...it created this frantic anxiety whenever the player heard a monster that required a fast visit to the menu."

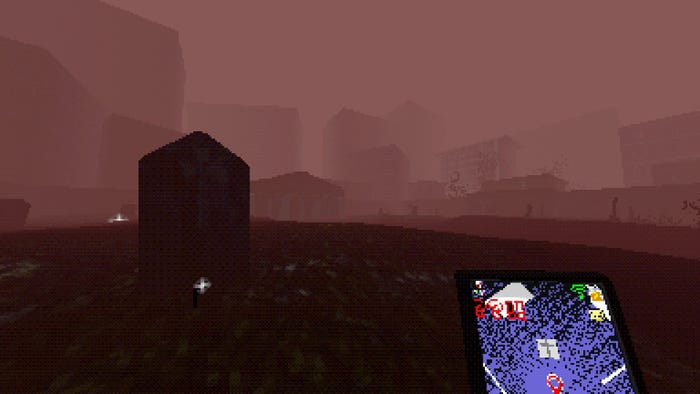

Beyond the Phone Screen gives players an in-game AR game called Civilian Go through which to explore a gloomy world and complete fun little tasks that will help them get to know the town. ...Except in this case the town is filled with dangerous monsters that don’t exactly like you mucking around the place. Picture Pokemon Go, but if there were lethal beasts actually wandering the streets you were exploring.

Game Developer spoke with David Rodríguez, Perfecto Carballo, and David García about creating their horror take on an AR game, discussing the challenges that came from having players watch their app while wandering, how they came up with monsters that would work well with its exploration-based play, and how to create good scares when the player is free to go anywhere at all times.

Game Developer: What inspired you to make a horror game around a fake AR game? What made those ideas feel right together?

Rodríguez: While brainstorming ideas for the jam themes (Submechanophobia and Public Service Announcement were the themes for the HPS1 Summer of Shivers Jam, which this was made for) I was very interested in making something around a fake multiplayer experience. Something where the PSA was the devs communicating with the players. Perfecto told us about an App that would mark places on the map where, supposedly, something bad would happen, and how bad stuff would actually happen (supposedly). Walking through a city, dividing your attention between the phone and the real world, and having the objectives get creepier and creepier came from that.

What thoughts went into creating the AR game? Into connecting it to the game's horror elements?

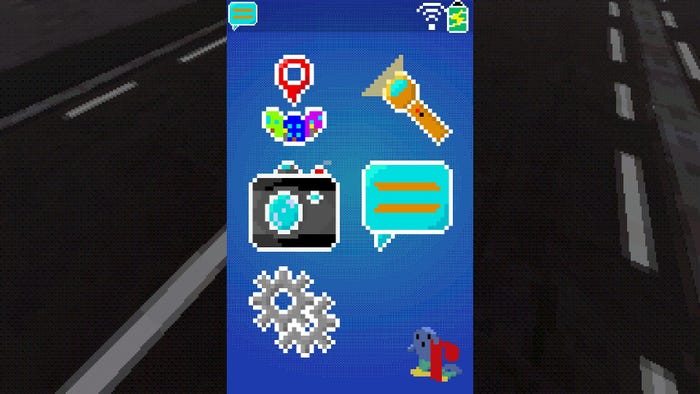

Rodríguez: We wanted to make it colorful and inviting. Perfecto focused on that for the pixel art and little jingles, so it’d create a contrast with the actual place you were walking around in. It was also the main gameplay hook to create danger from the limitation in your movements due to the need to use the phone. Someone in a YouTube comment theorized that the horror was a representation of the dangers people ran into while playing Pokemon Go, like cars and the sort, which sounds neat. But I’m afraid the connection to Pokemon Go is just the initial aesthetic.

What challenges came from designing two games in one, in a sense?

Rodríguez: The biggest challenge with game jams, for us, is usually having enough time to test and iterate to get the numbers right and make the game fun, or in this case, engaging. This being quite a long and big game in terms of jam scope, and adding to that the real map and the AR game point system, made this even harder. Positions for important events, avoiding the player getting lost, balancing the recurring events and monster attacks… It made for a lot of long tests.

What ideas went into designing the world the players would be wandering through?

Rodríguez: We went for a city big enough to evoke what we felt playing Pokemon Go back when it was the big thing, and of course, the main reference was the streets of Silent Hill 2 (just narrower). We wanted the buildings to be tall enough that you don’t have a great view of your surroundings and feel trapped, and to have to rely on the small window that the AR game provides into the area and the signs on the streets (which a lot of players ignored, and like, fair [laughs]). David (the other one) designed the whole map and gave it enough recognizable landmarks, nooks, and crannies to be an interesting place to get lost in.

That said, having the player explore it properly with the radar was the biggest issue once we released the game. We had to tweak both the explanation and the functionality of it a bit with a patch, since a lot of people were completely missing the main events.

The game features several monsters. What ideas went into their creation, and how do their abilities/behaviors tie into frightening players that are working through the AR game?

Rodríguez: Their ideas came first and foremost from “what kind of creatures could the player interact with using apps”. One that would be mostly invisible until very close to you that’s part of the game world, one that you need to use the flashlight app to defeat… And then with the first draft of the map and the main idea behind the Civilian Go themes, the streets seemed big and long enough to add an interesting threat [after] hanging around in them for too long. And then, if you add a statue, it has to come to life at some point. That’s the law.

While they come into play at specific points when playing normally, when the player takes too long, they all “wake up” eventually, which really took the people who got lost and didn’t progress at all by surprise.

With more time, this would be the area that would see more additions, alongside the main events. One monster that just barely didn’t make it was the reason for the name “YeeHaw Burger.” The cowboy in the logo was gonna be another antagonist.

García: The idea of an AR game possessing the minds of the people who play it was really appealing at the beginning, and the first designs were focused on creating these wild people who had been corrupted by the app and turned into grotesque versions of a human body. It led me to incorporate objects and limbs to these monsters that help the player understand how they can defeat them. For example, one of the monsters has these electric cables attached to them and a phone crushed into his head. This represents the need for the player to defeat them through the app.

In the game, there are also monsters that the player cannot kill. I had the idea that, instead of just people that had been corrupted for a long time, it would be fitting that parts of the city became monsters. I always think of the backstories of the characters (it helps me come up with details to add to the design), and I had this idea of a statue that didn’t want to be photographed. So, the AR game made them put a blanket over themselves and then play a sort of deadly peekaboo with the player.

If we had more time, I would have liked to further explore the relationship between Civilian Go and the city and create more monsters based on that. One thing that comes to my mind is that there are several ads scattered throughout the city talking about the app, and I have the feeling that turning them into a threat would be cool.

What thoughts went into the visual design of the AR game and the gloomy world? Into creating a juxtaposition between the unsettling world and the cheerful phone game?

Rodríguez: Perfecto designed all the pixel art and UI for the phone. He used old PS1 menu visuals as a reference (like the one when you check your memory card), and the mayor was written to be a huge asshole with a very clean and positive front.

One of the themes that didn’t get picked for the Jam was “capitalist nightmare” or something like that, but if there’s something constant in all horror games I work on, it’s that there’s always the looming threat of rampant capitalism [laughs]. For this reason, the PSAs you receive every few minutes in the game get more and more demanding and hostile, and all the landmarks you can examine on the map are basically telling the story of Civilian Go getting to control the city through sponsorship deals. Megacorporations intent on making profit over anything else always have a clean, happy, positive front, and here, that was the AR game.

What challenges came from creating a game where the player's attention is constantly split between the AR game on their in-game phone and the real world? What (potentially frightening) benefits came from it?

Rodríguez: It was difficult, programming-wise, to get the controls right. It was also hard to have the ever-present phone in the corner of your eye, to make it just useful enough to consider keeping the game app open. You can bring the phone app fullscreen without the PS1 resolution so it’s legible. Even the speed at which you bring your phone up and down was very important (and thus became a secret upgrade to find in the map).

Having monsters that have to be dealt with in different ways that require you to stop moving and fiddle with your phone was the core for the “difficulty” of survival. There are things that might seem weird, like needing to keep an app open to have your flashlight on and missing out on the map, but this is very intentional (and inspired by old phones that wouldn’t have a native flashlight app...), and it created this frantic anxiety whenever the player heard a monster that required a fast visit to the menu.

What sorts of ideas go into creating open-world horror as opposed to a horror game with more scripted moments and scares?

Rodríguez: It’s a whole different challenge. With the linear scripted games I worked on, the focus was on pacing those moments and making them interesting, but here you still have to worry about that (in the form of the main events) and also leaving enough bread crumbs around so a playthrough isn’t just mindlessly getting lost on misty streets.

We went back and forth a lot on how to keep the map from feeling empty or uninteresting no matter which direction you go, and so we needed to spread around the AR game landmarks, the scribbled notes, the secret upgrades, the coins, and vending machines, and then, hopefully, the random regular events would catch the player's attention in between the “puzzles”. Those puzzles were the trickiest to place around, since we wanted backtracking to be minimal and to feel fast and interesting enough, while also taking them around the whole map to check all the different set pieces.

It also affected the duration of the game, which was really hard to measure just testing by ourselves with no time to get fresh eyes on it… But luckily, people seemed to get into it and put a lot of time into the game, so it worked out.

What drew you to have multiple endings? What do you feel they added to the game?

Rodríguez: Multiple endings is the sort of thing I always want to try and include in a game (alongside secrets, but I didn’t have the time to do it until now). We didn’t have the time to do it this time either… But I was very stubborn [laughs].

We thought the multiple endings would work both as a motivation to get a higher score using the AR game by keeping people focused on Civilian Go and taking their time and as a hook for some of the secrets hidden around. It’s really interesting to see how some players find the hints, look for the pieces, and get the endings. Others never even find the clues and are blown away about all the stuff they missed, and a few just run into the secrets by accident and get a secret ending in 10 minutes! But I love all of them.

Marking the completed endings on the main screen gives people who enjoy the game a reason to really get into all of the corners of the map that David (the other one) put so much love into modelling. I would have loved to have some more time to make a couple of the endings a bit more interesting, and to have more information show up in the results screen (like how many upgrades you found, score, etc.) but it was ultimately the right thing to cut so we could get it out there.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like