Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

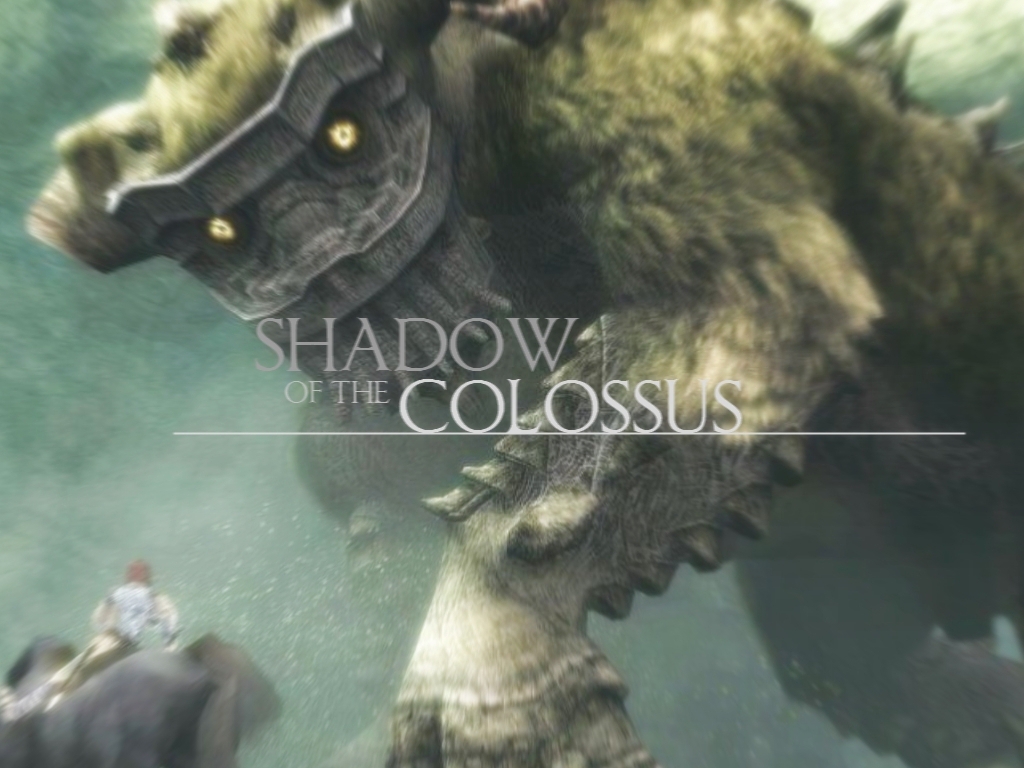

The first part of a thorough analysis of what makes this game one of the masterpiece of videogame art.

Here is the first a six posts series about Shadow of the Colossus, because this game is a no-brainer for me (and many others), when it comes to talking about art and video games. I will not write yet another review of the game, as there must be hundreds of them out there describing its contents and playability. Moreover, it is preferable for you to have completed the game, first to avoid spoiling your enjoyment, but also to understand what I'm talking about. This will spare me from having to describe the action or the scene before presenting its analysis.

Here is the first a six posts series about Shadow of the Colossus, because this game is a no-brainer for me (and many others), when it comes to talking about art and video games. I will not write yet another review of the game, as there must be hundreds of them out there describing its contents and playability. Moreover, it is preferable for you to have completed the game, first to avoid spoiling your enjoyment, but also to understand what I'm talking about. This will spare me from having to describe the action or the scene before presenting its analysis.

Before even displaying the home screen, the game presents the hero's arrival on the scene of the story. A prologue that sets the mood immediately: slow, without speech, just music, discreet, melancholic sounds, sensations. Everything is done to fill the player with the sentiment that what he’s going to live is somewhat discomforting, and pervaded by a deep feeling of solitude. In fact, as no dialogue, no word is spoken, we feel like wathcing a silent movie, the emotions being conveyed mainly by music and staging.

After the prologue, when starting a new game, the second part of the introduction is presented. After the entry of the hero inside the temple (in the same mood as the first part), appears a "divine entity", which tells the hero to accomplish the mission in order to revive his beloved. His intervention feels more that of a voice-over than a real protagonist of the game (at least until the final revelation): a simple indication, to the player’s attention rather than to the hero’s, for which no response is required. This divinity's interventions introduce each "mission", and they will be the only words heard until the epilogue of the game.

That's where the game really starts. At this point the player knows what to accomplish, but has not the slightest idea how to get there. He is released into this wilderness, empty, silent (no music is played at that time, but we will get back to this later). Only a few noises are heard (the wind, the cry of an eagle, the gallop of Agro) in order to establish a credible silence. The player can choose to take the time to run through the map, nothing will prevent him doing so. Only the instructions from the tutorial will attempt to guide him through his first steps, which, just like the interface, is unfortunately necessary, but somewhat spoils the immersion cleverly set up by the developers of the game. The player can experience as he wishes the isolation in which the game has immersed him. The developers have clearly played on the video-playing habits of players to always meet small opposition before facing one boss of the game.

This trick is magnified when meeting the first colossus. This is one of the biggest ones in the game, and the topography of the place where he lives is so designed that the camera, placed behind the hero, creates a low-angle shot effect, thereby making the colossus look even more impressive. One of the most enjoyable feature of this game is the use of the key that actions the camera and targets the Colossus (L2 if I recall correctly) to create some absolutely fascinating framing. Small details are added to emphasize this excessiveness which never seems artificial (such as these birds fluttering over the top of the giant’s head, which appear so very tiny on screen), his sluggishness of movement, and his steps and the ground-shaking blows of his sledgehammer. At first the battle seems completely unbalanced, but solving it is ultimately quite credible. The hero / player must use its only advantage (small size and mobility) to get rid of this behemoth, without ever looking "cheated", that is to say, driven by developers rather than by the player (here I have in mind God of War and its QTE used to get rid of the "giants" encountered in these games). Here, climbing the Colossus, reaching its weak spot(s) requires intelligence, cunning, balance, endurance and concentration, but no “super strength” which then would seem out of place. The qualities required from the hero are ultimately the same as those required from the player's in front of his screen. The player then has the true feeling that he has overcome an insurmountable obstacle thanks to his own skills, rather than his avatar's.

The other Colossi shall require more cunning, thinking, concentration and skill. Some colossi are much smaller and therefore do not suffer from the same lack of mobility as the biggest ones, therefore they will require different qualities to get rid of. By doing so, the challenge will be constantly renewed, but the avatar will never artificially increase its power to allow the player to pass these new obstacles. Each time, only the player will be asked to change his way of playing the fight. This is, in my opinion, an underused approach in games in general (at least, it is most of the time linked to the virtual progression of the player's avatar.)

In the second part, we will discuss the pace of the game, the design of the fights against the giants, and the scenario of the game (which is revealed at the very end of the game, but gives meaning to the whole adventure).

If you want to read more articles about video game as a proper art form, please visit my blog gameasart.net

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like