Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Tale of Tales' (The Path) Michaël Samyn examines how computers arose as a tool to successfully simulate game rules, how narrative was added later, and how removing both of these linear formats will allow for the emergence of a truly original and effective new art form.

[Tale of Tales' (The Path) designer and developer Michaël Samyn examines how computers arose as a tool to successfully simulate game rules, how creators imposed narrative on the process, and how removing it from the equation will allow for the emergence of a truly original and effective new art form.]

Not many people would argue against the pivotal nature of nonlinearity in computer technology. Many consider nonlinearity one of computing's most essential and exciting properties.

It is thanks to this nonlinearity that the computer has become such a useful tool, and has turned our civilization upside down. Why then is most of our computer-based entertainment so linear?

The joys of linearity are equally beyond dispute.

We love the tension that comes with a carefully constructed story arc. From Greek theater through medieval fairy tales and printed novels to stereoscopic high definition cinema, humankind has enjoyed storytelling for thousands of years.

We're also very fond of the games we play. We love to compete against each other, we love to measure ourselves against a given set of rules, we love the excitement of getting better at something. We love to control, to strategically manipulate the parameters of a system towards victory. We love to win.

The computer is a versatile machine. And it has enhanced many old forms of entertainment. Computer technology has added a new level of realism to the special effects in movies. And computer technology has made it possible to play games on our own, or to compete with people on the other side of the globe.

It has also added a new dimension to drawing, photo manipulation, writing, engineering, sculpting, and so on. This is thanks to utilitarian computer applications that take advantage of the computer's capacity to process data in a nonlinear fashion.

Stories and games amuse and enlighten us by virtue of their linear nature.

But a creative, expressive form that has grown out of this inherent potential of the technology has not emerged yet. Once in a while, video games make us dream -- by showing us a glimpse of the power of nonlinear entertainment. But they always end up disappointing. Because they seem to be stuck in either or both forms of linearity: the linearity of narrative, and the linearity of competition.

Both games and stories are linear. They are sequential constructions of causes and effects strung together by means of game rules or narrative logic.

Narrative is not an essential element of games. But it is often easy to add a narrative layer to a game, as it develops during play -- even to a board game or card game. Because games involve relationships between elements, and it's very human to pretend that these elements are characters in a story. So games can easily be told as stories, stories of conflict. But at their core, games don't need stories. They are systems, sets of mathematical equations, logical constructions that the player can combine and play with.

As such, from quite early on, games and computers seemed to be a match made in heaven. The rigid logic of computer technology formed a perfect framework for the precise rules of games.

Computers and games: a match made in space.

(Dan Edwards and Peter Samson playing Spacewar! on the PDP-1 Type 30 display, circa 1962, almost half a century ago -- before I was even born.)

But of course games weren't the only thing that a computer could do really well. As time went on, computer technology became increasingly successful at presenting and manipulating images and sounds. And video games followed that evolution every step of the way -- and often even drove it. So computer games started looking and sounding ever more attractive. And the fantasies that we used to make up while playing now seemed to materialize before our eyes and ears.

Gradually, almost imperceptibly, video games evolved from a kind of digital sport for nerds into something that was deceptively similar to a medium. Their sophisticated graphics looked a little bit like cinema and the linear progression of competitive interaction felt a little bit like the stories we knew from popular fiction, about good defeating evil and knights saving princesses from dragons.

So we got ambitious and started telling tales through video games. Our little pawns became characters with names and histories. These little creatures engaged in simple relationships with each other. And we built worlds around them where they could live their little lives.

As the technology continued to offer more opportunities, we were able to model the looks of our characters, the way they behaved and the environments in which they lived with increasing detail. More so than had happened before in any other medium! Because the moves of our players were unpredictable. And we wanted to make sure that everything looked good and believable from any viewpoint at any time. We were not just producing images. We were building worlds!

With the increasing number of pixels and polygons in their presentation, the ego of our game heroes grew as well and we wanted to know more about them.

(Source: Infendo)

As we perfected the presentation of our creations, the backbone of our designs shifted from the linearity of competitive gameplay to the linearity of the narrative arc. Our characters and worlds simply demanded this. We could not create their appearance in such detail without also creating a story for them.

Our games became longer. Not because our intricate systems of rules and goals were endlessly replayable. But because developing our characters required that we lead the player through carefully constructed plots. From an all-knowing godlike player moving pawns on a small board, the player turned into a pawn himself, moved around by the great will of us -- the tellers of tales.

This was a silent revolution. It opened up the video game experience to people who had little interest in competition or sports. They wanted to live through a story. They wanted to be a pawn. Or "the lead actor in an action movie", as we lovingly thought of them. We were still making games, but more and more people experienced them as stories.

We were okay with this evolution. Not just because, thanks to the increased audience, video games were making us more money than ever before. But also because, by that time, our attention had already shifted towards storytelling. All we needed to do was inject points in our story where we asked the player to do things.

This is where the actual game happened. We stop the linear progress of the story and replace it by the linearity of a game challenge -- a challenge that the player needed to win before he could continue. This the last testament to our heritage of competitive game design.

Or did we demand victory because all of our stories were centered on an invincible hero protagonist?

We have accepted the fact that some people find our challenges too hard, or not challenging enough (in the sense of mentally stimulating or inspiring), because the very vocal hardcore minority of players, who have been with us from the beginning (proverbially speaking that is, because they tend to be mostly teenage boys), really enjoys the competitive element.

But this means that we are kind of stuck. On the one hand, we are stuck with stories about conflict and heroism that grew out of our juvenile gaming fantasies.

And on the other, we are stuck with interactive designs that require victory, which actively prevent our audience from experiencing the immense virtual worlds and sophisticated characters we build -- the production of which becomes ever more demanding in terms of effort, skill and money.

So much beauty, so much effort, so much depth... but largely inaccessible to a broad audience.

(Gears of War, Crysis)

Despite of the limited potential to expand its audience, the game industry might find a way to survive in this impasse. But it seems like an awful waste of a perfectly fine medium. Especially considering that a different approach to game design would open up the medium to everyone.

In hindsight, often many of the most impactful discoveries in history seem so obvious that it astounds us that nobody had come up with them earlier. I think the same will be true for interactive entertainment. The solution to the frustratingly unhappy marriage between competition and narrative in video games is quite obvious. It is enclosed in the very words that we use to describe the medium: "nonlinear" and "real-time". In practice, both words mean the same.

The word "real-time" tells us that our art form is not a sequential one. Our medium is about what happens right now. It's a medium of the moment. We have far more in common with painting and architecture than we do with literature and film. The former capture a moment, freeze it in time, on canvas or in stone, for us to explore at our leisure. Not just any moment, of course, and not any old place. They capture a carefully chosen moment and a very specific place in a way that can be deeply subjective.

Experiencing real-time media is much more like exploring a painting than following a movie. In Delacroix's The Death of Sardanapalus there's a seemingly infinite amount of details for us to explore. On the other hand, the meaning of Curtiz's Casablanca relies completely on its narrative thread.

Nonlinearity may be an unfamiliar concept with regard to our technological media -- print, radio, television, and cinema are all linear forms. But it is by no means alien to human existence. In fact, linearity is rather rare, and only really exists when carefully constructed.

We never really find ourselves in a situation where there is only one thing available for us to do. Or where there is only one reason why we're here, or only a single motivation to go somewhere else. Most of the time, there are multiple things to do, multiple reasons, multiple motivations -- some of which we may be aware of, others not. Even doing nothing presents us with a myriad of ways in which we can do nothing.

But we don't experience such a situation as a multitude (of choices, or of reasons) however. That's a theoretical construction. As experience, the moment is indivisible. It is us in the cosmos. Life is not a "series of interesting choices". Most of the time, we "just do things". And it is only in retrospect that we can see how we made choices and how one thing lead to another. And even if we consciously make a choice once in a while, we can never predict the real impact of this decision. The nonlinear nature of the moment is very familiar to us. It is an essential part of life.

The concept of "the moment" serves as a starting point for both the experience of our audience and the design of our work in real-time media. It is inadvisable to create for a real-time medium in a sequential format.

Much like it is ludicrous for a painter to describe the picture he wants to produce rather than make a simple sketch, it is inappropriate for us to develop an interactive piece by means of written words or spreadsheets.

Much like the painter needs to see his brush strokes, we need to navigate through the world we are creating and touch it and poke it and play with it.

Designing for the real-time medium is a playful activity. This is because we are designing for interactivity; we are not purely designing rule sets anymore. We are creating situations in which people can have experiences. We are architects, we are masters of ceremony, we are priests and prophets.

We are designing the now. Not creating the event as such, but creating a situation. A situation in which events may happen. In which the player might experience a story of their own. All we do is carefully create the conditions.

But there does not need to be a story. This is why this medium is so revolutionary. It allows us to explore ideas beyond the logical constraints of cause and effect. In a space where many realities can exist simultaneously. Real-time technology is a poetic technology -- a medium that allows us to explore the infinity of a moment.

A useful model for nonlinear design is the utilitarian computer program. Applications like Photoshop or Word present us with palettes and toolbars and menus. But they don't tell us which ones to choose, or in which order to use them.

From experience (or from reading the manual), we know that for certain tasks, certain strings of commands are the most adequate. But that doesn't mean we need to do any of those tasks, or that we cannot achieve a similar (or more interesting) result in any other way. The creators of the program don't care which image or text you are going to create. But they do try their best to optimize your chances of creating a beautiful one.

A world of possibilities. And nobody telling us what to do.

(Adobe Photoshop)

The goal of playing a game is not to produce a drawing or write a text. The goal is to amuse oneself, which often amounts to seeking wonder in some way. This is where interactivity enters the stage. Utilitarian computer applications are generally not very interactive. Any action usually consists of the user pressing a button and the application executing the command. Interactive simulations such as video games, however, can do a lot more on their own. When the player does something, the application can respond in ways that can help them approach the wonder they are after.

There is no doubt that linear game design can produce a lot of amusement and wonder in a player. But its impact is limited, because its systems are designed in a top-down fashion. Like roller coasters, such games are designed by putting the right turns and accelerations at the right moments in order to maximize amusement in the player within a given set of constraints. To some extent, it is the lack of freedom that produces the desired effect.

Nonlinear design comes out of a bottom-up thought process. It centers around the act of playing. It's thinking in terms of opportunities rather than goals. When dealing with nonlinearity, we largely abandon game design as a discipline, in favor of more general interaction design. Our job is not to come up with challenges for our player, but to offer them opportunities to create their own amusement. We stop dictating what we think will produce fun. We have to remove obstacles, not build them.

The magnitude of the shift from linear media to nonlinear media should not be underestimated. Not only does it involve a drastic move away from the mass media that saturated the previous few centuries. It is also an enormous step in the evolution of artistic technologies, equal in gravity as the discovery of cave walls to paint on, marble to carve in, and using oil as a medium for pigment.

As such, we should not expect to see the full impact of this technology any time soon. Especially not since we started off on the wrong foot by allowing the medium to intertwine so much with competitive games and linear narrative.

But that doesn't mean that we should not start exploring the real-time aspects of the medium right now. Nor is it impossible to create impressive pieces long before the medium reaches maturity. In a way, this is the most exciting period in the evolution of an art form. Nothing is established yet. There are no conventions.

At this point, developing with video game technology is expensive. Especially on the blockbuster scale. So one of the smartest moves is to create new formats that allow us to deliver economically feasible products for smaller budgets, while at the same time explore our chosen theme in more depth.

This evolution towards more compact video game experiences is already happening thanks to broadband internet and the distribution channels that take advantage of it.

Three quarters of the development time of Thatgamecompany's PlayStation Network title Flower was spent prototyping interactivity in a world that had been defined from the start. This time was used to figure out how to express the chosen themes and emotions through interaction. (early XNA-based prototype of Flower, courtesy of Thatgamecompany)

Designing nonlinear entertainment is designing opportunities. It is virtually impossible to estimate which opportunities a particular setting or cast of characters can offer if we only have written text and images to guide us. To find out which activities will bring out the emotions and themes we want to explore, we need to work with the material.

We need to start by building a prototype. Not a prototype of mechanics or interactions but a prototype of the raw material: the environments, the objects and the characters we want to work with. We can start with cubes and cylinders. We can then gradually add more detail, both to visuals and sounds as well as to behaviors. Bit by bit, we make our world come alive! Interacting with our creation at such an early point can be a major source of inspiration.

And it prevents us from thinking in conventional terms too quickly. We don't need to worry about "what will people do in my world?" If we make that world and observe our players, we will know: a design will naturally grow, as if it had always been enclosed inside of our raw materials.

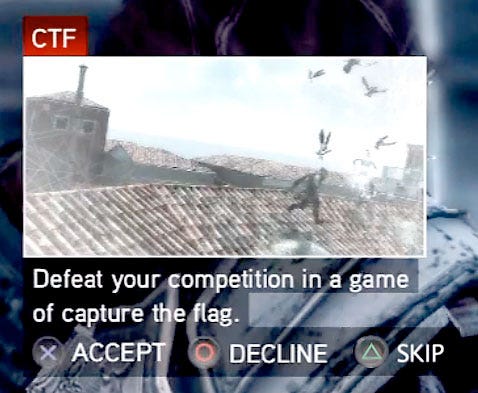

Of course, it will take some time for us to figure out how to author the entertainment in these real-time environments, especially when targeting a mass audience. But an easy risk-free step that can be implemented right now in any contemporary video game design is a simple "skip" function for gameplay sequences, as we already have one in most games for non-interactive cutscenes.

Modern video games consist of three major elements: gameplay, cutscenes and real-time exploration. We have seen the importance of the latter grow over time. Almost every blockbuster game now contains a considerable "sandbox" element. This has progressed to the point where playing video games now feels mostly like an explorative adventure interrupted once in a while by a gameplay mission or a cut scene.

Some people don't like the cutscenes. We allow them to be skipped. Other people don't like the gameplay bits. It's only fair that we allow those to be skipped as well. More so, considering that cutscenes are finite, and gameplay bits potentially endless (if the player fails the mission, there's generally no other option than to restart.) Ironically, in programming, such an endless loop is considered an error.

It's really not that hard. Just allow the player to choose whether they want to do a particular activity or not. This prevents a lot of frustration and negative sentiment. Plus, more importantly, it allows everybody to access your entire game! (Mission 57 in Assassin's Creed 2 with photoshopped "SKIP" option.)

I believe this small intervention will teach us a lot about real-time entertainment. Because it will allow the player to potentially remove the two linear elements (games and movies) from their experience. Even if skipping a cut scene or a gameplay sequence doesn't automatically make a video game nonlinear, being able to do so, will allow many players to truly begin connecting with the glorious worlds that the developers have so painstakingly created. And by carefully observing their in-game behavior, we will learn how to design for this new medium.

Computers have made their impact on society thanks to their capacity for nonlinear processing. Yet our computer-based entertainment remains largely linear, gridlocked in competitive and narrative structures. Stories have turned video games into a medium. But now it is time to take the next step. We need to embrace the real-time nature of this new medium and explore its potential for nonlinear entertainment, enlightenment, wonder. I believe this is the key to the maturity of video games as a medium and its break-through to the audience at large.

A new artistic approach is needed to unlock the power of nonlinear entertainment. Writers need to stop thinking in prose and drama. The real-time medium is a poetic one. And game designers need to broaden their attention to the full spectrum of interactivity. We need to become painters of situations, architects of worlds, poets of the infinite, designers of the moment. Our time is now.

This article owes a debt of gratitude -- and the inspiration for its title -- to Professor Cécile Alduy's observations and statements regarding the status of story in contemporary culture, as expressed in her blog posts Against Narratives, Against Narratives II and Against Narratives III.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like